EXCLUSIONS, EXEMPTIONS, SCIENTIFIC NARROWNESS, NATURE versus NOMADIC CULTURE

Blog two of two on UNESCO WORLD HERITAGE IN TIBET:

What the World Heritage experts have failed to notice is that most of the Tibetans were removed well before the World Heritage nomination process began, specifically to the Chinese petrochemical industrial city of Gormo, hundreds of kms to the north.

Nomad removals have been implemented since the start of this century, in the name of tuimu huancao, watershed protection for China’s great rivers. It is already too late for worrying about “deprivation of traditional land use rights of the concerned communities.” Most of the nomads, who worked so hard to protect antelopes from slaughter, have already been removed, and officially inspected by core leader Xi Jinping on his 2016 inspection tour of Qinghai province and the city of Gormo.

Nomad removals have been implemented since the start of this century, in the name of tuimu huancao, watershed protection for China’s great rivers. It is already too late for worrying about “deprivation of traditional land use rights of the concerned communities.” Most of the nomads, who worked so hard to protect antelopes from slaughter, have already been removed, and officially inspected by core leader Xi Jinping on his 2016 inspection tour of Qinghai province and the city of Gormo.

Xi Jinping declared their resettlement, in concrete blocks on either side of the highway into Gormo, a success. He was photographed being greeted by smiling Tibetans who are now utterly dependent on state handouts, having totally lost their livelihoods.

The experts did notice that grazing pressure has reduced, especially in the eastern portion of the proposed World heritage area, in what China calls the Sanjiangyuan, or Three River Source area, which has long supported Tibetan populations. The experts, however, tend to see this through China’s gaze: “Intensive grazing and human-wildlife conflict is also a current threat in part of the property, within Sanjiangyuan Nature Reserve. Sheep and cattle compete with wildlife for food and heavy grazing can cause the degradation of the grassland ecosystem. The government has an effective policy for reducing animal husbandry offering incentives and compensation to not graze the land to the relevant households. The IUCN mission understood that grazing intensity has fallen substantially in the last years, and thus it is recommended that this present policy is continued.” Yet again, the assumption that humans and grass are in contradiction is inbuilt in China’s approach, and often in the science of ecology.

NATURE/CULTURE

The IUCN/UNESCO experts focus almost entirely on the “natural values” of this pristine “no-man’s land”, as that is the basic category of classification for which China has applied. UNESCO sharply divides its World Heritage sites in two categories, natural and cultural. Seldom is a protected property classified as both, though there is no reason why a protected area cannot be both. Indeed, the major Chinese Buddhist pilgrimage mountains of China are classified as both natural and cultural World Heritage, at China’s request.

After many thousands of words, the experts sent by UNESCO do get around to briefly considering the culture of this depopulated but huge chunk of the Tibetan Plateau, the size of Denmark and Netherlands combined. “The IUCN mission noted that, in addition to the traditional grazing practices, there are tangible and intangible cultural attributes within the nominated property, including sacred mountains and sites, of local and national significance. Every village has its sacred places and some of them are inside the property and the buffer zone, mainly prayer sites linked to natural features like caves, hills or mountains.”

Because Kokoshili and the Sanjiangyuan are traditionally sacred, local Tibetan environmentalists, inspired by their experience working with global NGO Conservation International, have been calling for the area to be declared a Sacred Natural Site, under community control. That way they would have an ongoing role as guardians and stewards of land and animals, able to continue what an earlier Tibetan generation died for, to protect the antelopes. That story is movingly told both in film and print, in the 2015 book Tibetan Environmentalists in China, and in the 2004 hit movie Kekexili: Mountain Patrol. Both come from Chinese writers who fully entered into a Tibetan worldview, enabling audiences to understand Tibetan sacred natural sites through Tibetan eyes.

When it comes to the crunch, having raised Tibetan culture as inherent to wildlife conservation, UNESCO’s experts merely say: “IUCN notes that the cultural and spiritual values of the area should be recognized and included in planning management strategies for the nominated property, noting the intimate linkage they have with the nature conservation values that are the basis for the nomination.” China has much experience in brushing aside such vague suggestions.

AMNESIA MAKES ROOM TO BRING THE STATE BACK IN

China now brushes aside its own history of community conservation, with Tibetans at the forefront. If we turn the clock back less than 15 years, it was a very different story, with Tibetan rangers celebrated as heroes of China’s lawless wild west, by Chinese citizens all over China. The movement to save the Tibetan antelopes from slaughter by immigrant Chinese miners/poachers was a citizens movement, led by Tibetans, celebrated throughout China, a highpoint of popular solidarity uniting Tibetans and Han Chinese alike, in common cause.

This is best captured in the 2004 hit movie Kekexili: Mountain Patrol, and in a book published in English, also in 2004, by the Chinese government’s Foreign Languages Publishing House, Tracking down Tibetan Antelopes. In 160 pages of glossy colour photos, both the antelopes and the Tibetans are lyrically embraced as China’s darlings. In the last words of the book: “No animal has ever aroused as much attention among the Chinese people as the Tibetan antelope. Numerous people are concerned about this endangered species, and offer to help in various forms. Some have even died for this cause. The efforts to protect the Tibetan antelope form the most heroic and stirring page in China’s history of wild animal protection.”

This citizens’ movement showed up the state as missing in action, a deep embarrassment for a state determined, above all, to stamp its sovereignty on lands it had conquered centuries ago but had never effectively ruled. Even as this century began, China had yet to make its empire into a nation. That had to be rectified, by bringing the state back in, as sole actor, sole agent, sole authority, disempowering everyone else.

China’s nomination of Koko Shili as exclusive property of the state, with the blessings of UNESCO World Heritage, is the culmination of more than a decade of placing the state in command, displacing everyone else, starting with the disbanding of the Tibetan Wild Yak Team of ranger patrols.

Only one year after the antelopes and their Tibetan protectors were celebrated across China as heroes, the tone changed. In 2005, Beijing Youth Daily, an organ of the Communist Party’s youth league, announced that national interest was at stake. Koko Shili is the source of China’s greatest river, the Yangtze, and that water source must be fully protected from all threats, especially nomadic Tibetans, who were depicted solely in negative terms: “The no-man’s land of the Qinghai-Tibet plateau, known to Chinese and foreign scholars as “the world’s highest natural zoo”, has more than 40 national grade-1 and grade-2 protected animals, including the Tibetan donkey, wild yak, snow leopards and black-necked cranes, and at present it has some of the fewest developed areas in the world. It is also an important environmental protection area and water source for our country, with numerous rivers and lakes. The Mother River of the Chinese Peoples – The Yangtze – also rises in this area.”

Having invoked the national interest, it was a short step to depict Tibetans as an irrational, mobile, unpredictable danger: “Liu Wulin, Principal of the TAR Forestry Research Institute and an expert in wildlife, said that aside from the large numbers encroaching on the two nature preservation areas of the Qiangtang and Kekexili, another 100,000 km2 of “no-man’s land” outside of the two protection areas also has nomads in residence or human activity. The latest survey shows: 392 people, 7200 head of cattle and more than 40,000 sheep have moved into the protection area. As was seen during a visit to this area, there are already nomads living around the 5000m-high Fenghuo Mountain pass, with more than 1000 sheep and more than 200 yaks put out to graze on the mountain slopes. At a place along the 3146 km Qinghai-Tibet Highway, there were also nomads who had put out more than a thousand head of livestock. Buqiong said that at present there are already more than 400 nomad families living within the protected area, primarily concentrated around the Nuola, Mayi and Qiangma Cuo areas. The population of the Twin Lakes Office is already more than 10,000 people, and there is human activity in more than 100,000 km2 of the uninhabited area.”[1]

For the sake of China as a nation-state, what is pristine “no-man’s land” must remain pristine, not contaminated by the presence of Tibetans. From 2005 to China’s 2016 nomination of Koko Shili as World heritage, in a 200 page nomination document using the term “no-man’s land” countless times, is a direct line.

In this new narrative, inconvenient truths were ignored. It mattered little that some of the nomads who moved into Koko Shili had done so at the directive of officials, implementing policies to spread grazing pressure and enhance pastoral production. It mattered little that the nomads had been required to build fences, which now impede wildlife migrations. It was not only the celebration of Tibetan rangers that was swept aside, so too were earlier official policies.

Today, in 2017, amnesia reigns. Mandatory amnesia (known in Chinese communist jargon as avoiding historical nihilism) is common in today’s China. The patriotic Chinese students who flocked to Tiananmen Square in 1989 to protest corruption and make China great again, may not be mentioned. The Tibetans of Koko Shili and Drito who, in the absence of the state, confronted and captured the antelope poachers, are similarly erased from memory.

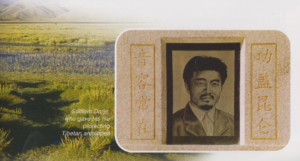

There is however, a single exception. Of the Tibetans whose ranger patrolling saved the antelopes from extinction, one name stands out, the martyr Sonam Dargye. In classic Chinese fashion, his image has been appropriated, his memorial made a shrine, his memory a tourist magnet. In his death, he magically became Chinese, a hero of China’s determination to save the antelopes, which the state now inherits, with the blessing of World Heritage branding. Sonam Dargyey (Soinam Darje in Chinese) lives eternally as a feature of China’s Hoh Xil World Heritage. If conquering Genghis Khan and Kublai Khan can be made into Chinese emperors, it is not too hard to make Sonam Dargyey a hero of state protection of “no-man’s land.”

HOW MANY TIBETAN NOMADS HAVE BEEN REMOVED?

Although UNESCO has sent its own IUCN mission to Koko Shili, and in June issued a further 11,000 words reporting their findings and recommendations, UNESCO’s biggest failing is in not noticing that, well before China nominated Koko Shili, most of the nomads had been removed to the outskirts of industrial Gormo city. There is not much point in now talking (vaguely) of indigenous rights when most of the Tibetan population of the whole area, in compliance with explicit policies announced in 2003, has already been removed.

Can we know how many Tibetan pastoral nomads have been excluded from their pastures, to lead aimless lives on the urban fringes of Gormo? Administratively, the nominated World Heritage area is largely to the east of Koko Shili, and includes the counties of Drito (Zhiduo in Chinese) and Chumarleb (Qumalai in Chinese) as well as Koko Xili (Hoh Xil or Kekexili in Chinese). This administrative spread is noted by the UNESCO evaluation mission, which enumerates the staff numbers designated as wildlife protection officers as 49 in Drito, 49 in Chumarleb and 37 in Koko Shili. We also have current population figures for “no-man’s land” revealed in China’s nomination: “According to the nomination, there are 35 households of 156 herders within the nominated property, and 222 households of 985 herders and 250 other residents in the buffer zone.”

That is a total of 1391 humans, all Tibetan, living in the 75,000 sq kms designated for World Heritage status. If we consult China’s official Year 2000 Census, we discover the Tibetan population of Drito county was then 23,407; in Chumarleb county 23,601. This strongly suggests China first removed most of the Tibetan nomads, and only then initiated the UNESCO World Heritage nomination process.

Touchingly, China (the State Party in UN jargon) has reassured the IUCN Hoh Xil evaluation mission that the few remaining nomads will not be coercively removed: “In response to concerns raised, the State Party has stated unequivocally that there will be no forced relocation or exclusion of the traditional users of the nominated site, whether before or after succeeding in the application for World Heritage site.”

[1] http://news.xinhuanet.com/st/2005-09/06/content_3448651.htm 可可西里保护区被大量侵占 青藏高原无人区锐减 Kekexili protection area encroached by large numbers, no-man’s land of the Qinghai-Tibet plateau falling 2005年09月06日 08:21:00 来源:北京青年报 September 6, 2005. Source: Beijing Youth Daily