Blog one of four on the Chinese film industry in Tibet #gabriellafitte

Gang Rinpoche is a story of a farming/herding family, their everyday piety, the routines of taking out the yaks to graze, of going to the woodlands to gather firewood, cut to length and split, loaded onto pack yaks, to be stacked near the house. Always in motion, always something that needs doing. Humdrum everyday life in Kham Markham, southeastern Tibet, where the trees are plentiful. This film is also known as Paths of the Soul.

The first suggestion of plot movement is the old guy who announces he really wants, before he dies, to do the pilgrimage to the distant holy city of Lhasa. Within minutes, many others agree to join him, no drama, no tension or argument, the woodheap is high, the autumn tasks of preparing for winter are done. We are about to go on the road.

The road, the path broad or narrow, the journey within or without are all metaphors occurring repeatedly throughout Tibetan and Buddhist culture. The spiritual journey within is mirrored and enacted by the pilgrimage journey without. Lena Herzog and her film maker husband Werner titled their book on Tibetan pilgrimage, Pilgrims: Becoming the Path Itself.[1] Kham has plenty of pilgrimage sites of its own, such as the holy Khawa Karpo mountain.[2] But Lhasa is a once-in-a-lifetime special.

The path is the path of practice, of familiarisation with the methods of self transformation, so they become embodied, ingrained. The entirety of Buddhism and its many methods can be reduced to ground, path and fruition; meaning a preparatory intellectual understanding of the logical coherence of the teachings, the path that does the work of a change of mind, and the fruition of fully awakening to the nature of reality.

“You cannot travel on the path before you have become the path itself”; a saying the Herzogs attribute to the historic Buddha: could this be the ticket for the cast about to take to the road? Or does it demand far too much from movie-goers for whom pilgrimage is at best exotic, unfamiliar? Must we too become the path?

Fortunately, this is a romantic confection, attributable not to Buddha but Blavatsky. From a Buddhist viewpoint one takes to the path in order to gradually familiarise, to eventually become the path; it’s not a prerequisite. Meditation practice, whether seated or on foot, is above all a familiarisation.

THE LOW KEY, COOLLY DISTANT CAMERA: PEMA TSEDEN AND ZHANG YANG

On this Paths of the Soul path the camera keeps a certain distance. Unlike the conventions of Hollywood drama, we are not fed emotion in close-up, or by a swelling score on the soundtrack. We are so used to being manipulated; we expect it. This is a movie in which the audience has to work to fill in the gaps, and we aren’t used to that, even when Tibetan directors such as Pema Tseden and Sonthar Gyal ask just this of us. Pema Tseden tells us he holds his camera back to give the viewer space to fill in the rest. Yet doing that work is all the harder when daily drogpa routines are no longer familiar, as is the case for Tibetans in scattered exile worldwide.

This is a movie that takes for granted that the viewer can and will contribute, can read into landscapes and faces what’s happening, beyond the undramatic dialogue of people who take risks every day, and routinely deal with them by deadpan understatement. Our ability to access conversations is facilitated by both Chinese and English subtitles, just as well since the spoken Tibetan is in such varied dialects that it’s clear this is not a doco, it’s a doco drama, an electric shadow dramatization of sama-drog semi-nomadic family life, acted by a cast from various places, chosen for their ability to be themselves with cameras rolling. More on that later.

The plan is to go in time for Losar, the midwinter heralding of a new year, a time of festivity and communitas, a traditional time for pilgrimage, when there is little to do at home, no grass to take the yaks to, only a few hands need stay behind to feed straw to the animals downstairs. Quite quickly, in plot exposition, the plan is amplified: as well as distant Lhasa, they hope to make it to the much farther Gang Rinpoche, the holiest of holy mountains, a journey of thousands of kms, especially auspicious because in the 12-year cycle, this is the most beneficial year to go. All this is sorted in the first 10 minutes. It’s all doco realism: this isn’t a musical.

THE BANAL AND THE SACRED

Back to the many tasks of autumn: grinding the harvested barley for tsampa, spinning the shorn wool, drilling an awl through wood to make a frame for yaks to carry loads. All so everyday, all so unfamiliar to Chinese and international audiences alike. It’s easy to see this as humdrum and boring, lacking in cues that alert us to conflict, or even just a little tension. Attention wandering, we may wonder if this is meant to be timeless, ahistoric Tibet, or maybe decades ago, or maybe today. Incidental details: an electric motor to grind the barley, the puffer jackets, baseball caps, motor bikes, solar panels, a mobile phone, quietly bring us into the present. The sacred journey is through the mundane.

More of the complexities of life emerge in conversation, dealt with matter of factly: if you plan to do lots of prostrations while on pilgrimage, can you do it while pregnant? No problem. “Yes, I can.” That’s all it takes to decide. We are all of 12 minutes in. Shots of ewes lambing take longer. Likewise the butchering and freeze drying of a slaughtered young yak, all part of the autumn harvest. Facts of life on the pasture.

The village butcher is also the village drunk, he knows full well the consequences in lives to come of taking life, and wants to join the pilgrimage to atone. Again, everyone agrees: he’s in.

JUST ADD MINDFULNESS

How can it all be so straightforward? Where’s the agonising, or a dramatic turn where the wrongdoer awakens? There’s none of that: we are among people for whom a deep trust in Buddha, dharma and sangha, and especially in the living Buddhas, is immanent, pervading all questions, all decisions. Even the tension between caring for livestock day in day out, and having to slaughter a few for winter survival, has a ready resolution. Is this for real? We are still only 14 mins in and already too much has happened, yet seemingly nothing much has happened.

This is where the viewer really has to work, to imagine life as an individual and in a community defined by deep faith, a life dedicated to the inward path unseen by the lens, with the dedication modernity devotes to education, career, accumulation, values and individuality. How to imagine that? How to believe it when we see it?

Winter has arrived, the ground is white, the chorten stupa is white, the khatag offering scarves are white as the men walk up to the white latse flags to replace the faded white lungta prayer flags. The pilgrimage party is growing, it’s new year’s eve, which means an early start next morning. 16 mins in.

We now know who is going on this road movie and why, what motivates each one. two more are going because in a collective effort to build their house two men died, so two men in the owner’s family will do the pilgrimage to make amends.

A child can’t be left behind, it’s beyond an elderly grannie to care for her, so she too will go. It’s all so matter of fact.

WHERE’S THE DRAMA?

Is that why it is so hard to engage, and why the film flopped? How can we identify with so many people so quickly, enter their world and go on the road with them, when they all agree so immediately to an epic life-changing road trip?

We know our road movies: it’s a quest, usually for the unknown, for the rainbow, rather than for an awakening familiar to all. We know our noir: everyone has darkness within them. We know our kung-fu movie; the answer to everything is in who has the best moves. We know our historical romances, we know our genres and suspend disbelief accordingly. So why can’t we enter normal Tibetan rural life? Why does it seem abnormal, unbelievable, impossibly pious?

Men cut hand-sized wooden blocks to slide hands along freezing roads in full length prostrations, women cut and sew sheepskin aprons to keep warm. Preparing for this road takes more than a tank of gas, and it’s all home-made, apart from the sneakers, bought by the dozen.

These are the practicalities of the inner journey through the outer world. A trailer is loaded with bedrolls and jerry cans; this is a major undertaking, but it’s all do-able. Hitched to a basic two-stroke tractor, we are off, victory banners strapped to the sides. We are 21 mins in, more than 90 to go. Crank the engine, cross the bridge and onto the sealed road, China’s gift. As the tractor putt putts ahead our pilgrims start their relay race, clacking the hand sandal wooden blocks strapped to their hands, taking refuge in guru, Buddha, dharma and sangha; head, throat, heart and down they go, one by one on the narrow, icy road, leaving plenty of room for traffic.

Only now do we start to see close-ups, of bodies sliding on the bitumen. Very soon, a pause for tea from the thermos, another Chinese gift, as the ten prostrators, young and old sit or lie on the road, shielded by the tractor as motorbikes and VW Santana race past.

HUMAN BODIES ON & OFF ROAD

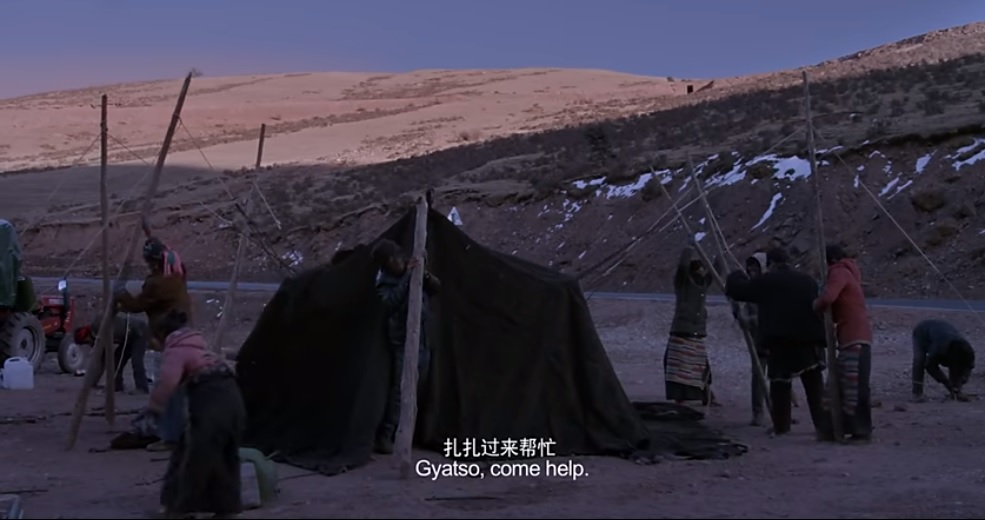

When the sun is low they find a sheltered spot, between road and a small stream, unload the trailer: poles, steel spikes, hammers, a heavy woven yak hair tent rises, slung over the poles. Bedrolls are hauled in. By the stream, the women ladle water into the empty plastic jerrycans.

As dark falls, trucks sweep by on their long and lonely traverse, but inside the tent everyone is toasty, round the cast-iron stove, eating and comparing sore muscles. Day one is done? Not yet: first everyone chants in unison the praises of Tara, the fierce protector, who liberates all, the swift heroine, whose eyes are like an instant flash of lightning. Only then does each one wriggle into sheepskin bedding, lights out.

Morning is signalled by a Highway 318 milestone marking 3436 kms, all the way to Shanghai far, far to the east, proclaiming this two lane blacktop to be a national, nation-building road. In Tibet, Highway 318 runs westward, from Chaksam to Dartsedo, Nyagchu, Lithang, Bathang, Markham, Palsho, Pome, Nyingtri, Kongpo Gyamda, Meldro Gungkar, Taktse and then Lhasa. One of only two east-west highways, soon to be upgraded to a four or even six lane expressway, this is a major artery of modernity. Many centuries ago the great yogi Thangtong Gyalpo built his iron chain link bridges across major Tibetan rivers, to facilitate pilgrimage; now China’s gift unrolls across Kandze, the big trucks roaring past.

TIBETAN MODERNITY

China’s gifts are not edited out, as if Tibet is timeless. Nor are they made central, as if China’s investments are the core of the story, making this long distance pilgrimage possible. The tractor is clearly another gift, with slogans painted on it in Mandarin (and Tibetan) signalling it is fupin kaifa ,扶貧開發, meaning “poverty alleviation and development.”

Tractors, jerrycans, milestones, highways, mobile phones are simply part of life, to be taken as we find them because the whole approach of the pilgrims is to take life as they find it, with neither attraction nor aversion, praise or blame, a thoroughly Buddhist approach. How undramatic. China, however, does expect its gifts to be received with manifest gratitude. The anthropologists remind us gifts are conditional on reciprocity, even an entire economy of gifts and mutual obligation.[3] China’s gifts insist on gratitude in response. The quid pro quo is unspoken yet compulsory.

On we go, in single file in the morning sun. Already the sneakers are starting to look scruffy. Gyatso, the girl child in the rear walks on and on with the head/hand/heart clacking of the hand sandals, to keep up. Walking is faster than prostrating, or kowtowing as the subtitles misleadingly call it.

Lunch by the roadside, the iron stove smokes, butter tea is churned, frozen meat is sliced and chewed. In the evening we are camped by a frozen river, good for an improvised skate, pulled alongby mother. Wielding a wood splitter, one of the men breaks up enough ice for the pot to go on the stovetop. Inside the tent, it’s time for running repairs, restitching sheepskins, filing rough spots on the hand sandals, regluing loose sneaker soles. It’s all so damn practical, this business of inner transformation. Are we watching a movie or an extended Youtube manual on Prostration 101?

BARRIERS TO ENGAGEMENT

Are we unable to get more into this movie because it’s all unconvincing amateur acting, or an inept director? Is it because director Zhang Yang is working in a language he doesn’t understand? The Tibetan director Pema Tseden faced similar problems in casting and filming The Search back in 2009, with similar incomprehension among audiences in exile, who preferred to believe old Tibet had long disappeared.

Like Pema Tseden in The Search, Zhang Yang’s focus is on deeply religious Tibetans on the road. Pema Tseden went on the road in 2009 searching for a contemporary Drimé Kunden; seeking someone as selfless as Drimé Kunden, the operatic Buddhist model of unhesitating compassion, willing to take out his eye for a rapacious blind beggar who demands it.

To the modern mind, the figure of Drimé Kunden, for starters, has to be mythical, his exemplary offering of an eye utterly exaggerated over centuries of retelling. Drimé Kunden is a figure from classic Tibetan Lhamo opera, thus not from real life? To go on a quest, through modern Amdo for anyone with similar generosity has to be a fool’s errand. To modern minds, Pema Tseden and Zhang Yang alike are asking us to believe the unbelievable; so our difficulty with entering into Gang Rinpoche isn’t so much that the director is Chinese. Zhang Yang is mindful that any movie audience is going to need more context, more background, and tries hard to provide it without being too obvious.

Both directors give us long shots rather than close ups, trusting us to do the emotional work for ourselves, rather than manipulating us to emote on cue. Pema Tseden’s movies are hard to relate to because he doesn’t set the scene enough; while Zhang Yang is hard to relate to because he tries too hard to contextualise? Can’t both be true, surely.

It took a while before Pema Tseden was appreciated beyond Tibet, but now he is widely respected for bringing a distinctively Tibetan eye to film making. Pema Tseden, rather than pushing us to believe a lost Tibet still exists, “deconstructs the myth of a pre-existing Tibetan people, and builds upon individual and fragmented narratives to create a new collective subjectivity, thus opening the way for a new understanding of Tibet. This case study demonstrates how Pema Tseden’s in-between position (between languages, cultures and geographical areas) permits him to develop a cinema that gives space for Tibetans to become, giving the viewer a rare insight into contemporary Tibet.”[4]

CRISIS

Back on the nékor pilgrimage, a high mountain is close, the sky is ominous: mountains make their own weather. In the morning it’s snowing, with a stiff wind, but the prostrators keep at it, while in the gloom heavy laden trucks roar west and empty trucks roar east.

Camping spot for the night is near an isolated farmhouse. Politely they ask for firewood. It is readily offered; everyone respects pilgrims, who do it to end suffering for all.

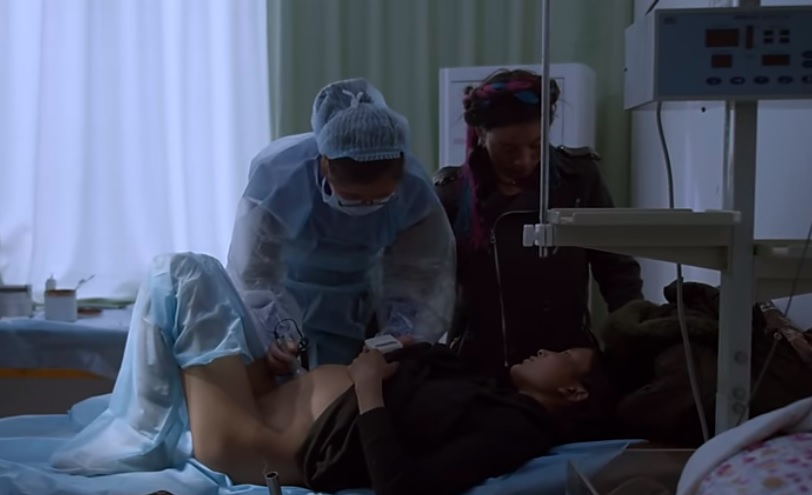

In the night our mother-to-be goes into labour, is helped into the trailer, the tractor cranked by torchlight, off into town and yet another Chinese gift: a small hospital, white coated staff, sterile set up, a baby safely delivered. All is well. It’s a boy, truly a child of the road. The rest catch up by taxi van, everyone crowds around, the baby is named. Can mother and newborn go right back out on the road, in midwinter? They can. Is this too little plot or too much? Can we believe that women used to nomadic mobility, used to being far from modern facilities, can just keep going?

To be born, or die, on pilgrimage is highly auspicious, we are reminded. The new family do get the warmer of the two tents. Next morning the newborn, swaddled in sheepskins, gets to ride in the trailer, everyone else is back on the blacktop.

THIS FARMING LIFE

Reaching a house build, all local timbers, they are hailed over and invited to share tea. “We are from Markham”, our group explains. By the milestones they have done 141 kms, Shanghai is farther than before. The home builders say they wish they too could walk and prostrate all the way to Gang Rinpoche too. Next year.

The girl’s head hurts. Can Gyatso keep going till Pangda, the next town, where our Highway 318 meets up with Highway 214 from the north, all the way from Xining? Yes, she says. There will be a pharmacy in Pangda. During tea break a man worries: should she keep prostrating? Yes, her mother says, it’s good for you. He asks Gyatso directly: can you keep this up? I can, she says.

Really? Can we believe? Is this bravado, or group pressure? Or bad script writing? Maybe none of these: two months of prostrating all day every day actually does change the mind, making everything possible. Since liberation and enlightenment are possible, the Buddha tells us, this intensively embodied experience of body, speech and mind working together might just do it. Theory meets practice. We are still only 50 mins in, an hour to go.

At a stop overlooking a river far below, they stop to build stone cairns to local gods of place, Gyatso fetches the last rock to top it off, clearly she’s ok.

Next day, as the highway zigzags in switchbacks downslope, we see our party from far above, then in close up, as last night’s invocation of Tara the protector continues, one of the few moments where sound runs on beyond sight. On and on, chanting, praying and prostrating, through icy landscapes, tunnels blasted through cliffs, portions of highway roofed by avalanche shields, on and on. By now, watching this is either dead boring, or awesomely riveting.

DISCIPLINE

There’s to be no shortcuts either. A grandpa appears, a self-appointed disciplinarian gegu: make sure your forehead touches the pavement; to the girl Gyatso: less walking, more prostrating; to the young Khampa warrior: take that red braid out of your hair. This is all said with the same absence of affect as everything else said, just do it, plain and simple, no drama.

Turns out this grandpa isn’t just a stickler, he also invites them all in to his farmhouse for the night and, since the tractor is leaking oil having lost a screw, which could take a while to fix, they’ll stay a day or two and help with the new year ploughing. This interlude is a collective effort, as always. Some ploughs are pulled by walking tractors, some by yaks. Ploughing is festive, a coming together of the clan. Being sama-drog, farmer-herders, our pilgrims know how to plough. The grandpas wonder why the young are in such a hurry these days to get it all done, time is not short, spring is still ahead, there’s hay stored up on poles beyond the reach of the yaks. There’s snow on the ground, a portent of soil moisture sufficient to start the barley crop, come spring. These are the facts that matter, along with a pious heart, and an aspiration to fulfil the vow to the lama to merge the mind with his enlightened example.

In plain language grandpa reminds us of the right frame of mind for doing nékor pilgrimage; lamas have said it more poetically:

“Without desire,

attachment, or any particular agenda or itinerary,

With no selfish concerns, simply roaming freely from place to place

For the sake of others, benefitting impartially those to be trained—

This is the way of the very best type of pilgrim.”

WHAT MORE COULD BEFALL?

We are halfway through this movie, time for a plot recap, explaining to host grandpa that the village butcher is off alcohol altogether as part of making up for slaughtering livestock. Grandpa is delighted, he’s not such a grinch after all. He even gives Tsering Chodon a new sheepskin, the old one’s worn out.

Back on the road yet again next morning, Tsering Chodon takes a break to breastfeed her baby. Passing a loose cliff face, there’s a rockfall, the young man doing his nékor pilgrimage because men died while building his house, is injured, hit in the leg. In the tent he laments his misfortune, first the accident when a truck overturned and the two men died, then the compensation payment, now this: is this divine displeasure? “I just don’t understand why this has happened.”

We moderns know shit happens. It’s random. The group’s father figure reminds us of the Buddha’s timeless advice: this is the human condition, to suffer is normal, what matters is motivation, and our disheartened young man has not wavered in his motivation, to benefit others. So it’s all good, we’ll just rest a couple days, and recuperate. No itinerary.

PROSTRATING THROUGH PARADISE

The poverty alleviation tractor, China’s gift, chugs on, put to Tibetan use to assist in the transformation of poverty stricken mind, a novel and profound use never imagined by the developmentalist donors. As the lamas say: “One of the problems we have is feeling poverty-stricken. To overcome that, we have to be direct, and we have to trust ourselves. We are not poverty-stricken. If we are capable of smiling, we have goodness in us, always. Whether young or old, very old or very young, still, there are always possibilities of a smile. So keep smiling. Enjoy your goodness.”

By now we are nearing Nyingtri, we can tell by the peach blossoms, it must be March, the rapeseed crop is turning the fields yellow, spring comes early here. Time to lessen the heavy clothing, wash hair by the river. They hail another pilgrim, a naljorpa yogi from even further, from the foothills of Tibet in Sichuan, accompanied by his wife pulling a handcart, and their donkey. So why is she in the shaft, not the donkey? It’s precious to her, we are told, not to be overworked, it’s only for pulling uphill. “We see the donkey as family, we go through thick and thin together.” He is to be taken round the Barkor circuit of blessings too when they reach Lhasa, we all need liberation. They have been on this pilgrim path nearly eight months by now. Pitstop over, a top-up of tsampa flour, and it’s back on the road. This was filmed before the Nyingtri expressway sliced across lakes, now nowhere to go when trucks roar towards you.

Why does so much go wrong? Hit by falling rocks, illnesses, an unexpected birth, blizzards, trucks hurtling at everyone, and eventually a death. Are these simply plot devices to hold our interest? Narrative hooks? Overly programmatic directing? Actually, pilgrimage is meant to be hard, purifying work, an experience of the bardo, the limbo between worlds, between moments, between one life and the next. Pilgrimage is meant to be challenging, as the great 19th century pilgrim Shabkar reminds us:

“When I made the pilgrimage of the Tsa ri ravines/ When traversing with difficulty the treacherous paths/ The rivers and bridges of the land of Lho/ It occurred to me that it must indeed be like this/ When travelling the perilous paths of the bar do.”[5]

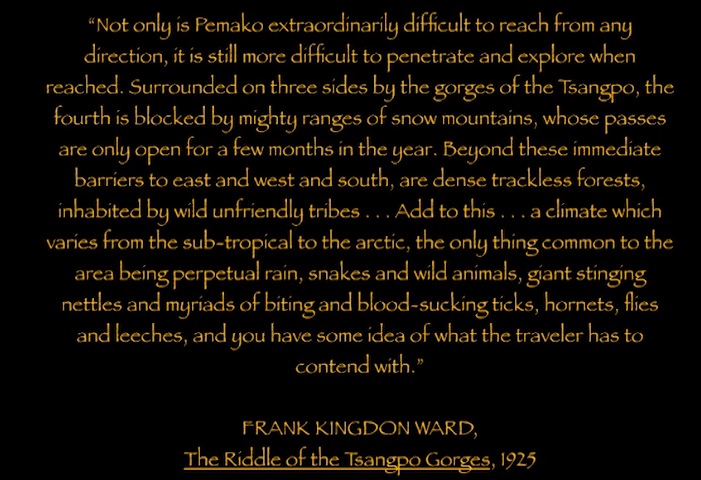

The hardships of pilgrimage were vividly expressed a century ago by an English plant hunter, Frank Kingdon-Ward, whose greedy motivation for entering the beyul hidden land of Kham Pemako was to collect flowering specimens that might adorn English gardens:

Past the peach blossoms that these days make Nyingtri/Bayi a favourite of Han tourists, and briefly into Bayi town, buying more sneakers in bulk, 30 at a time: they don’t last but are cheap. Nyingtri (Linzhi in Chinese) these days has its own Hilton hotel.

A moment later, we are out in the fields again mountains and clouds towering above. This is the road to Lhasa, soon to become the high speed electrified rail line from Chengdu to Lhasa as well. What takes the pilgrims months will be trip of 13 hours, the railway constructers tells us. Pressurised, heated, insulated the whole way. Progress.

COLD AND WET

Next challenge: the highway fords an ice cold stream. What to do? It’s not dangerous: SUVs heading the other way cross readily, the tractor and its trailer would too. But they decide together to not only go through on foot, but to continue prostrating. Only the baby and the tractor driver get it easy. No wonder their sneakers wear out quick.

However, this isn’t a via dolorosa penance: the wet clothes are taken off, dry ones put on. Practical.

Camping for the night by a big river means another drenching, from the rain. Summer is close. Time for a reminder from our grandpa that we all by now have bumps on our foreheads, but what counts is not action but motivation, a pure heart, no need to be a Drime Kunden, “what matters most is your heart; if your forehead hurts, it reflects piety in your heart, and kindness.”

CRASH

A hundred kms from Lhasa, the inevitable crash. An SUV rams the tractor, no-one too badly hurt but the front axle is broken, the wheel is off, spare parts a long way ahead or behind. What to do? Is this a modern Trials of Job? What more could befall them?

With much the same resourcefulness nomads need on the grassland when disaster strikes, the men pull and push the trailer a ways ahead, then walk back to the tractor to complete their unbroken prostrations. No shortcuts. Repeat, uphill.

Camping yet again, approaching the pass, from there it’s downhill to Lhasa. Phone reception is good up here, time for the girl to phone grandma back in the village near Markham, they miss each other.

Up, up to the pass, no motorists stop to help. Hauling the trailer by hand is hard, even with all hands pushing. Breaking into a ragged song of ascent, where the chorus line is that we may have the same mother, but our paths in life differ, some are more fortunate than others. We accept the results of past karma; as for future karma, we make our own, here and now.

Finally the pass is reached, festooned with prayer flags proclaiming victory to the gods, a moment to tie on a few more, and refresh the battered old trailer with new victory banners, as the prostrators catch up. Everyone tosses their sheaf of tiny paper windhorses to the winds.

THE HOLY CITY

Downhill is so easy, joyful all the way, camping on green grass, dancing barefoot in a circle dance, the trials of Job it is not. But one quarter of movie time is still ahead, and we are at Highway marker 4504 kms to Shanghai. It’s the urban fringe, the Potala in the distance. The holy city has been attained.

Inside the great temples our ragged pilgrims join the throng, touching foreheads to altars and to an empty throne: whose throne could that be?

With the right motivation, you can ignore the lenses of the Han tourists and the official posters of China’s Tibet, and keep the mind on what matters: receiving the blessings of the Buddhas and bodhisattvas, making them tangible, a lived experience. Tibetans do still know how to do that, and be changed by it.

Khatag silk scarves at the ready, it’s time to meet Lama Thubten, a distant uncle, who has been busy giving teachings. He knots their scarves, the knot of communitas. A special blessing for the baby.

In their cramped urban lodging, time to wash clothes, and think about pressing on all the way to Gang Rinpoche, Mount Kailash. But money is short, and the tractor still needs repairs.

As always Buddhist economics intervenes. A woman at the window is unwell, and lama Thubten has instructed her to purify by doing 100,000 prostrations. Can she pay them to do it for her, she just can’t manage it herself? Why of course. And, as their patron, the benefits accrue to her, she has fulfilled the lama’s instructions.

Something will always turn up. There’s also the itinerant work gigs available in a city where Tibetans do all the low paid unskilled work, cleaning cars to look like they belong in town, stacking scaffolding on construction sites. Our men, in hard hats, go to work. Hardly Chinese gifts, just the precariat work of the global gig economy.

But by night, when the tourist crowds are gone, they can do their nékor round the Barkor circuit, undistracted.

Time has passed, the baby is almost walking. Money in hand, time to move on, even if it means leaving a budding romance.

BACK ON THE ROAD

In a flash we are out of the city, but where? Out of the fog our prostrators emerge, on the road again, where it can snow even in summer. We are at the holy Mapam Tso, Lake Manasarovar, camped by the shore.

Then at last Gang Rinpoche, the holiest of mountains and fount of Tibetan civilisation. On the 53 kms kora circuit around the mountain, our young mother has baby strapped to her back, taking the prostrations well, but grandpa is struggling. Prostrating through the talus in snow and scree is not easy.

Waking up in the yak hair tent, grandpa Yangpei has died. Quick, get a lama to make sure his consciousness has left, and is free to deal with the bardo. Father delivers an impromptu eulogy: he was a good man, raised kids when the wife died young, he loved invoking the Buddhas to be tangibly present, he never picked quarrels, was always kind, now he has died at Gang Rinpoche, this is a blessing. Passing away here connects him to the holy mountain.

Monks arrive, chanting the mantra of compassion. Seated on the ground, the unmistakable holy mountain in the background, with damaru hand drum and drilbu bells they offer the body to the circling vultures, as the family brings out their progenitor in a winding sheet, laid at the feet of the monks. It is complete, it is finished, life goes on. China today prefers to eradicate all evidence of the departed, and many Han Chinese now mourn the death of graves.

MEMORY

A little below, the adult sons make small cairns of granite stones, adorned with the dead man’s boots knives, and silk scarves. A little tsampa is sprinkled on another rock where a small fire gives of fragrant smoke, another offering to unseen spirits, a signal to the vultures.

That’s decisively the last goodbye, time for everyone to move on, in this world or the next. On with the leather aprons, on with the prostrations through the scree of the great peak. The best of tributes to grandpa is to keep right on. Slowly, the entire group passes from right to left and off-screen, Gang Rinpoche majestically unmoving, overlooking all.

The final scene is a long shot, all white snow and looming slopes, the pilgrims small in a vast landscape, the clacking of woodclad hand against hand the only sound. We are done.

This is a neglected movie that prompts many questions, explored in the next blog. #gabriellafitte

[1] Lena & Werner Herzog, Arcperiplus, London, 2002

[2] Alexander Patten Gardner, The Twenty-five Great Sites of Khams: Religious Geography, Revelation, and Nonsectarianism in Nineteenth-Century Eastern Tibet, PhD dissertation, University of Michigan, 2006

[3] Emily Yeh, Taming Tibet: Landscape Transformation and the Gift of Chinese Development, Cornell, 2015

[4] Vanessa Frangville (2016): Pema Tseden’s The Search: the making of a minor cinema, Journal of Chinese Cinemas: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17508061.2016.1167335

Dan Smyer Yu (2014) Pema Tseden’s Transnational Cinema: Screening a Buddhist Landscape of Tibet, Contemporary Buddhism: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 15:1, 125-144, DOI: 10.1080/14639947.2014.890355

[5] Mathieu Ricard, The Life of Shabkar, SUNY, 1994, 254