CHINA’S HI-TECH AMBITIONS TO SUPPLANT THE WORLD’S TOP MANUFACTURING COUNTRIES, BY EXTRACTION OF RARE STRATEGIC METALS FROM TIBET

Blog #2 of 2

LITHIUM, HI-TECH STEALTH BOMBERS AND THE DAM PLANS ON THE NYAGCHU/YALONG RIVER

Even though extraction on a commercial scale has barely begun, lithium mine construction at Lhagang/Tagong is confined to warmer months and few operations are yet in production, the early signs are not auspicious. The mass fish kill that alerted local communities in Lhagang/Tagong indicates a careless approach to local concerns. This is especially puzzling as lithium is not a toxic metal, although beryllium is. Since the fish kill was hushed up by censorship and denial, we may never know what caused it. However the rock surrounding the lithium veins is largely granite, which is naturally acidic, and that may have sufficed to change river water chemistry enough to kill the fish and alarm the Lhagangpa community of Tibetan farmers and pastoralists.

DAMMING THE RIVER FOR HYDROPOWER, AND FOR WATER DIVERSON

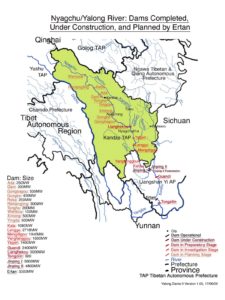

The mineralised district is close to the Nyagchu river, which also gives its name to the county town. This river, flowing from NNW to SSE, in parallel with the lithium veins, is a major tributary of the Yangtze far below. For 600 kms it dissects Kandze prefecture, through dozens of Tibetan Khampa villages, before plunging from the Tibetan Plateau not far north of the Tibetan Autonomous County of Muli/Mili and down to the Sichuan basin. Most of its course is also parallel with the Yangtze/Dri Chu further to the west, before the Yangtze eventually makes its eastward turn towards inland China.

The Nyagchu river is known in Chinese as the Yalong Jiang, scheduled for impoundment in at least 11 pinch points, as it rushes down from its origins in the north westernmost corner of Sichuan, as it protrudes into Qinghai province. Not only are many hydropower dams planned but, above them all, is to be a dam of a quite different sort, announced in the 13th Five-Year Plan from 2016 to 2020 as a “big reservoir” for diverting water away from Tibet and from the Yangtze, through tunnels in the mountains, across to the upper Yellow River, to the cradle of Han civilisation, a river these days parched, overused and laden with waste. China sometimes argues that its dams athwart Tibetan rivers merely interrupt flow briefly, holding water only long enough to drive the turbines that make electricity; but a big reservoir is, as the name suggests, designed to impound as much water as possible, to be built as high as possible, and hold water as long as possible, since the rains are in summer but the Yellow River is in most need of more water in winter.

The engineers who have long looked at maps showing the upper Yellow River is tantalisingly close to upper tributaries of the Yangtze not only have to drill tunnels 100 kms long through the mountains, but also shift billions of cubic metres of water uphill, because the Yalong/Nyagchu and other Yangtze tributaries are inconveniently lower than the upper Yellow River at their closest points. Pumping water against gravity requires enormous energy. One solution is ingeniously simple: build the dam walls so high on the Yalong/Nyagchu that the water level is raised, eliminating much of the pumping. The result will be the tallest dams in the world, well over 300 metres high, requiring a massive construction effort, and huge immigrant construction crews in the remotest areas.

TIBETANS PROTEST TO PROTECT THEIR LANDS

The entire mineralised area, the geologists tell us, shares a common history of metallogenic formation. The known deposit already covers three counties: Kangding, Yajiang, Daofu in Chinese, Dartsedo, Nyagchu and Tawu in Tibetan; but similar conditions elsewhere make further discoveries likely. Tawu has a very troubled history in recent years, with peaceable Tibetan assemblies shot by security police.

Tibetan water policy specialist Tashi Tsering writes, in a UNESCO publication: “in May 2009 thousands of angry Tibetans protested against the proposed Lianghekou dam project near Tawu County, Karze Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, part of China’s Sichuan Province. Reports describe instances of local people being forced to sign documents for relocation amidst vehement local opposition. Protestors led by a 70-year-old Tibetan woman destroyed a symbolic stone pillar that officials had erected to signify dam construction and relocation plans. Armed police, dispatched to control the protestors, opened fi re at the angry protesters, leaving six Tibetan women wounded. Such incidents, sadly, are not isolated cases.”[1]

High above the Nyagchu riverbed, on ridgetops at around 4300 m altitude, is good farming country, especially at Nyagrong/Nyenrong, both Tibetan spelling signifying farmland, known as Xinlong in Chinese. There, in March 2017, a young Tibetan man publicly burned his body in protest at China’s encroachments.

These lithium and rare earth mineralisations seem to have occurred long before the collision of the Indian plate with Eurasia brought close to the surface what had formed deep within the molten heart of the planet and then cooled so slowly it took four million years for liquid to crystallise and solidify into rock. This gives us special access to the inner depths of our planet.[2] It is little wonder Tibetans regard such places as special, and routinely perform rituals to keep local spirits happy.[3] Only in very few places on the planet’s surface is the earth’s inner mantle accessible.

THE SECURITY STATE SEEKS DOMESTIC SUPPLY OF STRATEGIC MINERALS

This patrimony is to be used to establish China’s dominance in robotics, surveillance satellites, electric vehicles, drones and innumerable military applications. These are metals that are light, resistant to corrosion and with many special properties that are being pioneered by military technologists. Large drones, made for military use, armed with bombs, are made in Chengdu, close to Tibet, by a state-owned corporation with roots in western China going back decades to the decade of Soviet cooperation in assisting China leapfrog its military industries as far inland, away from the US Navy, as possible. The same Chengdu based company is making advanced attack aircraft.

Because these technologies, reliant on Tibetan minerals, offer China a pathway to global dominance in its chosen industries of the future, high tech industries worldwide are expressing alarm at what they call mercantilism, making clear this is not free trade, the inevitable trajectory of globalisation or a level playing field: “China has doubled down on its innovation-mercantilist strategies, seeking global dominance across a wide array of advanced industries that are key to U.S. economic and national security interests. And despite the claims of some apologists for Chinese behaviour, it’s clear what the end game is: Chinese-owned companies across a range of advanced industries gaining significant global market share at the expense of American, European, Japanese, and Korean competitors.” [4]

Sourcing key strategic minerals from Tibet is intrinsic to this centrally-driven plan. China has long been a global buyer of raw materials, including just about all metals, and has learned how to not only buy and trade minerals but how to buy mines worldwide. But certain minerals are considered strategic, their acquisition backed by national stockpiles, their export restricted, with state regulation and ownership playing a major role. Once a mineral is classified as strategic, its extraction and storage are no longer solely commercial issues left to market forces, they become part of the security state and its priorities in an anarchic world of competing sovereigns.

Now that public opinion throughout China demands effective action to protect the environment, especially the rivers, there are now serious new regulations making it: “forbidden to build new heavy and chemical industry zones within a kilometre of the Yangtze and major tributaries, and those already present will have to be relocated.” However, these “red lines” only affect the officially designated Yangtze Economic Belt, which only begins far below Tibet and covers territory further downriver. What is the point of restricting mining, heavy industry and chemical plants along the mid-Yangtze, while the upper Yangtze in Tibet is polluted with toxic rare earth mining? This is a real opportunity for Tibetan and Chinese environmentalists to discover they have much in common, and work together.

A major reason China needs Tibetan sources is that its factories are moving to the foot of the Tibetan Plateau, away from the high-cost east coast, where urban populations are sick of polluting factories and frequently rise in effective protest. For coast-based industries, it makes little difference whether the mineral raw materials they process originate in Zambia or Peru or Tibet. But for the hi-tech factories based in Chengdu, far inland, close by the Tibetan Plateau, it is only a 200 kms journey to the lithium/tantalum/niobium/beryllium deposit of Lhagang/Tagong, close to a highway which is being rapidly upgraded by central authorities. AVIC, the drone and stealth fighter maker based in Chengdu was a pioneer of establishing the Third Front, as the military industrialisation of western China decades ago was called. Now Chengdu boasts of having most of the world’s top 500 corporations operating factories in Chengdu. AVIC hopes to make it big, becoming a world player, or at least big enough to squeeze nonChinese manufacturers out of China.

A recent in-depth report by analysts in Germany points out: “The hopefuls are a large heterogeneous group, including large state-owned and private enterprises as well as many small and medium enterprises. Examples for hopefuls are the state-owned aircraft and defence corporation Aviation Industry Corporation of China (AVIC), as well as the TV maker Changchong, energy equipment producers such as Shaangu and the ship maker Nantong COSCO KHI Ship Engineering. Many hopefuls take part in the pilot projects launched by the MIIT and local governments.

“Policy is the main trigger of industrial upgrading. Unlike the frontrunners, the hopefuls rely on the top-down approach of Made in China 2025. For them the policy campaign is the main driver for their upgrading activities towards smart manufacturing. Their business interest is currently too weak to lead to comprehensive investment in cutting-edge automation and digitisation technology without policy support. But the national pilot projects are an important trigger and provide substantial support for testing advanced technology and improving efficiency. Senior managers of large state-owned enterprises respond particularly well to the policy priorities of Made in China 2025 in order to meet political targets and advance their own careers. The big push towards smart manufacturing is especially visible in the aviation industry (Table 5). State-owned aircraft makers have considerably increased their activities in this area in 2015 and 2016. AVIC, for instance, developed a comprehensive plan for smart manufacturing parallel to the release of Made in China 2025.

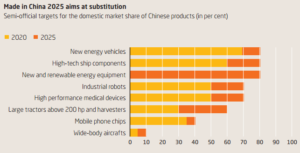

“The government puts all necessary political and financial resources into making Chinese tech suppliers dominant in politically selected industries like robots and high-end machine tools. The envisioned market shares for Chinese products and brands in the “Made in China 2025 Key Area Technology Roadmap” demonstrate the ambitious political goal of reducing the market share of international technology suppliers. Over the coming years until 2025, China’s policy makers will increasingly intervene in the market to achieve these goals. The Chinese government will use the whole array of innovation and industrial policy instruments to enhance the competitiveness of Chinese suppliers in politically selected industries.

“Capital injections for Chinese companies:

“The national and local governments nurture tech suppliers with generous state support. This includes, for instance, tax rebates for high-tech enterprises and for software developers. There are also huge direct capital injections from government funds and innovation parks.

“The central government shows extraordinarily high ambitions for the development of the Chinese robotics industry: Chinese robot makers are supposed to reach a domestic market share of 80 per cent by 2025, according to the “Made in China 2025 Key Area Technology Roadmap”. For sophisticated core components, the target is 70 per cent by 2025. To realise these ambitions, the government will again intensify its political incentives and funding mechanisms in the robot industry in the years to come. The state’s subsidy glut has led to a tremendous increase in the number of Chinese robot companies. More than 800 Chinese robot companies are registered in China, approximately half of them in 2015. The majority of these companies have not yet reached the stage of mass production. Many of them just serve as rent-seeking vehicles to receive government subsidies and do not make any profit.

“China’s high ambitions and extensive political support for the manufacturing sector will reshape global competition structures. Despite the weaknesses of China’s top-down policy, a group of Chinese companies will be able to utilise the political support effectively and significantly boost their competitiveness. And these emerging companies will continue to enjoy intense state support. The Chinese state will seek to shield their activities from international competition at home and to support their engagement on global markets politically as well as financially. The global competitive playing field will be effectively tilted by Chinese industrial policy. This poses a number of fundamental challenges to industrial countries and international enterprises. The Czech Republic, Germany, Italy, Hungary, Japan and South Korea will be most vulnerable if Made in China 2025 is successful.”[5]

High tech manufacturers in the US and Europe are worried China plans to take their market share, by any means. This has resulted in many recent in-depth reports and watchable online video hearings on China’s Made in China 2025 state-driven developmentalist strategy.

Those reports reflect the fears of China’s competitors that their technological edge will be bought up by China, their intellectual property stolen, their markets shrivel. They highlight China’s plan, in the first stage of the Made in China 2025 strategy to substitute China-made technologies. They focus on the knowledge needed to substitute Chinese high tech products, both military and civilian, for imports. They seldom ask where China will obtain the raw materials for domestic manufacture of high tech on the scale envisaged. This is what concerns Tibetans, as the Lhagangpa, with their precious lithium, tantalum, niobium and beryllium aren’t the only source China has in Tibet, not only of minerals but also the water essential to manufacturing, and the electricity.

TIBET PROVIDES CHINA A FULL MENU OF MINERALS & ENERGY OPTIONS

The wider picture is that Tibet abounds in proven deposits of copper, gold, silver, molybdenum, lead, zinc and many other minerals, plus, in its salt lakes, abundant supplies of lithium, potassium and magnesium, and a host of other accessible minerals as well. China’s plans for damming most Tibetan rivers to generate hydropower for transmission right across China to coastal manufacturing hubs, was reaffirmed by the announced targets of the current 13th Five-Year Plan. Apart from the Tsaidam Basin in Qinghai, the Tibetan Plateau has seldom fulfilled China’s expectation of becoming a treasury of extraction, but that is now changing.

China’s program to transform itself into a leading hi-tech maker is state led. This is a directive, developmentalist, allocative model financed by the state, on a massive scale, to make China, over a decade, into a world leader in military and civilian high technologies. ”Frustrated that it was spending more on importing semiconductors than oil China has, since 2014, spent $150bn through a mixture of M&A and domestic subsidies on developing the sector. It has also poured money into its own national champions.”[6]

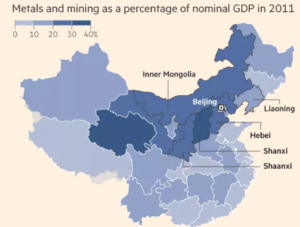

Already, extraction has transformed the economy of Tibet, especially in Tibetan areas beyond the Tibet Autonomous Region. Mining and minerals processing contributes more than 40 per cent of the GDP of Qinghai province (Amdo in Tibetan), a dependence equalled only by one other Chinese province, coal-rich Shanxi.[7] And that calculation does not include Qinghai’s export of its hydropower to the factories of Lanzhou downstream. When extraction dominates an economy, attracts all available investment capital and generates quickest returns, the primary agricultural sector is neglected, benefits flow only to those connected to the resource economy, in short, the resource curse. This is evident in Qinghai which, by area is well over 90 per cent officially designated Tibetan autonomous counties and prefectures, but its economy is dominated by extraction, in which displaced Tibetan no longer permitted to remain on their pastures sit out redundant lives on the fringes of the extraction zone, in settlements such as those lining industrial cities such as Gormo. They have no place in the extraction/processing industries, yet no place on the land either.

CHINA’S LONGER TERM AGENDA

Not only does China obtain the raw materials, energy supply and water it needs for its mercantilist grand plans for high tech dominance, on the ground in Tibet the party-state establishes its presence as the sovereign power. Through hydro dams, ultra-high voltage electricity transmission grids, mines and mineral processing plants, new towns and transport networks connecting all the extraction enclaves, the state manifests in the lives of Tibetans used to local self-sufficiency, with no felt need, over the centuries, for any distant sovereign power to take command.

China is renowned for long term plans and strategies, thinking far ahead. The Made in China 2025 program established a 10 year frame for achieving China as a high tech leader. But there is a much longer term agenda, seldom explicitly mentioned, of establishing alien rule as the norm across the Tibetan Plateau, the long haul of making an empire into a nation.

Alien rulers have limited options if they intend to persuade those they rule to accept being citizens of the modern nation-state, in which the ruled, on the frontier, are a distinct ethnic minority. States can only do certain things, notably infrastructure construction, frontier security, encouraging immigration, setting up penal colonies, promotion of new industries, strengthening of existing industries, enabling frontier populations to access metropolitan markets, investment in resource extraction and in the provision of environmental services to benefit distant populations. Beyond these, middle income countries such as China can afford to invest in effective rural health care for the frontier populations, veterinary care and livestock insurance for their animals, pasture rehabilitation for degraded and deforested areas, even basic minimum income payments as a right of all citizens.

On the Tibetan Plateau, over the past 60 years, China has tried many of these approaches, but has consistently favoured those that announce the presence of the sovereign state as the master, superseding all customary loyalties. Thus China has invested heavily, where possible, in immigrant population transfer (seldom possible in Tibet for climatic reasons), in massive infrastructure builds, and in security, an industry that dominates employment and the Tibetan economy; while neglecting to invest in land, livestock, pastures and rehabilitation of degraded areas, or to invest much in welfare. The state has done all it can to encourage, subsidise, agglomerate and intensify the exploitation of selected enclaves of highly focused capital expenditure and accumulation. These are the enclaves of resource extraction, water impoundment, subsidised urban hubs, cascades of hydro dams, and all the networks that link the enclaves –the highways, railways and power grids intrinsic to modernity.

A PREDATORY STATE

Not surprisingly, Tibetans feel left out, their livelihoods ignored or even prohibited, under the slogan of “grow more grass” (tuimu huancao) to ensure Chinese populations far downstream get more water. Tibetans, long used to self-sufficiency in local communities, experience the encroachments of the dam builders, geologists, miners and security police who repress dissent, as a state that is indeed powerful, but partisan and predatory, favouring its own Han ethnicity while punishing Tibetans who stand up for sacred mountains and local gods. Although China intends to make alien rule acceptable, it persists in alienating the ruled, widening the gap between Tibetan and Chinese identities. China’s policies are counter-productive, and have long been so.

The discovery of so many Tibetan mineral deposits essential to new high tech military and civilian industries fits closely with the priorities of a developmentalist, mercantilist state that insists this is development, with Chinese characteristics, for all, including the Tibetans who will somehow e pulled up out of poverty by all the new dams, mines, power grids, highways and cities now growing fast across Tibet.

When, in the 1990s, the revered lama Tulku Tenzin Delek, in the heart of the new lithium country, spoke up for the environment, was labelled a terrorist, gaoled, dying in prison almost two decades later, he understood China’s calculus, that his home district of Nyagchu/Lhagang was, in Chinese eyes, a source of primitive wealth accumulation, nothing more or less.

A predatory state focused only on extraction of hydropower, water diversion and mining of strategic minerals is counter-productive, if the long-term aim is to assimilate minority nationalities, encourage them to trust and identify with the nation-state, accept its sovereignty and identify as its citizens. China, at an official level, has persuaded itself that its predatory extraction constitutes a program of modernisation, which will eventually make Tibetans wealthier, and thus glad to be Chinese. All evidence of recent decades is that the more predatory the state, its hydro dam builders and state owned miners become, the more deeply it alienates and anguishes Tibetans.

Far from achieving the long term goal of assimilation, the 13th Five-Year Plan for hydro dams on the Nyagchu/Yalong, big reservoirs to capture and remove water, and the Made in China 2025 mining of precious strategic minerals, cause the perverse outcome of deepening the divide between Han and Tibetan, fostering a stronger sense of Tibetan identity.

If the world thinks “the Tibet issue” is gone, it is wrong: there is a long way to go.

[1] Tashi Tsering, Lessons from Tibet’s only successful anti-dam campaign, in: Water, Cultural Diversity, and Global Environmental Change, UNESCO International Hydrological Programme, 2012

[2] LI Jiankang, WANG Denghong and CHEN Yuchuan; The Ore-forming Mechanism of the Jiajika Pegmatite-Type Rare Metal Deposit in Western Sichuan Province: Evidence from Isotope Dating, ACTA GEOLOGICA SINICA (English Edition) 87 No.1 pp. 91-101 Feb. 2013

[3] Samten Karmay, The Arrow and the Spindle, LTWA 2006

[4][4] Stopping China’s Mercantilism: A Doctrine of Constructive, Alliance-Backed Confrontation ROBERT D. ATKINSON, NIGEL CORY, AND STEPHEN J. EZELL | MARCH 2017, Information Technology & Innovation Foundation,

http://www2.itif.org/2017-stopping-china-mercantilism.pdf?_ga=1.175527650.1596523250.1489815324

[5] Mercator Institute for China Studies (Merics), Made in China 2015: The making of a high-tech superpower and consequences for industrial countries,

https://www.merics.org/en/about-us/merics-analysis/papers-on-china/made-in-china-2025/

[6] Louise Lucas, Technology: China reboots its superpower ambitions: As Beijing pushes to be self-sufficient in tech by 2025, rivals see a threat to their national security and competitiveness , FT, 19 March 2017 by: Feng https://www.ft.com/content/1d815944-f1da-11e6-8758-6876151821a6

[7] Lucy Hornby, Archie Zhang and Jane Pong; Fake China data: was it just one province? Revelations Liaoning fabricated statistics raise questions over rest of rust belt, FT MARCH 13, 2017 https://www.ft.com/content/a5bf42e2-03cf-11e7-ace0-1ce02ef0def9