NATURAL AND CULTURAL WORLD HERITAGE in KOKOSHILI/HOH XIL:

TIBET’S EMPTY QUARTER OR HUMAN LANDSCAPE?

Blog 1 of 2 on the decision facing UNESCO World Heritage Committee in the first week of July 2017

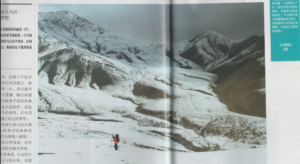

A remote, high, frigid land of lakes on the Tibetan Plateau is about to become news, thrust forward by China’s nomination of Kokoshili to be made UNESCO World Heritage.

Surely global protection is good? Unfortunately, that common sense response doesn’t always match well with how things turn out. If the iconic wild animals of Kokoshili are protected, while the human protectors are excluded, that’s not good. But that is what China proposes.f

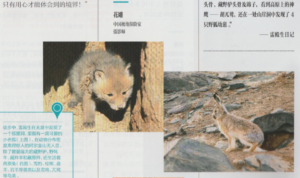

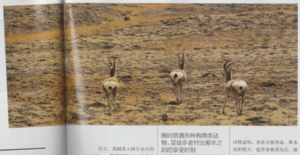

What is this unknown “empty quarter” of Tibet? Why has China singled out what it calls “no-man’s land” for global prominence? China depicts it as alpine desert, yet it teems with lakes, wetlands and wildlife, including the iconic Tibetan antelopes, snow leopards, bears and wild yaks. China proclaims itself the protector of these iconic species, yet under China’s control the number of antelopes plunged from one million to as few as 65,000. They were protected only by the Tibetan nomads of Kokoshili and nearby pastures risking –and losing- their lives to protect the nimble tsö antelopes from the slaughter of hunters making fortunes from their downy underfur.

KOKOSHILI: A HUMAN LANDSCAPE

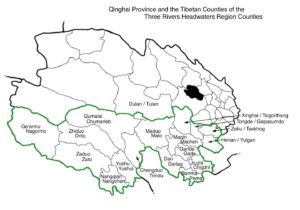

Tibetan communities of the arid pastoral landscapes of the Tibetan Plateau urge the UNESCO World Heritage Committee, its scientific advisers and member states to reconsider China’s nomination of what it calls Hoh Xil (in Tibetan: Kokoshili), to become a World Heritage natural landscape property. A decision on China’s nomination is due early July, on the agenda of a World Heritage Committee meeting in Krakow, Poland.

Classifying this huge seasonal pasture land solely as natural landscape, with no cultural value, betrays the heroic efforts of Tibetans to protect the endangered wildlife of Kokoshili and the adjacent counties of Drito, Chumarleb and Zato, much of which China has mapped into the proposed Kokoshili World Heritage site.

For the past 30 years the Tibetans of these remote areas have worked to protect both landscapes and iconic wildlife species, while seasonally grazing their herds of sheep and yaks, which have always intermingled freely with the wild antelopes and gazelles. In three decades of campaigning for the animals, sacred mountains and innumerable lakes of this land of frigid lakes, Tibetans have risked their lives to detain poachers, and lost lives to violent hunters and gold miners. The poachers were mostly poor Chinese Muslims. When the central state did little or nothing to protect natural resources, the Tibetans risked all. Yet now China insists the area nominated is “no-man’s land”, with no human presence at all, and so no local communities as stakeholders. This is a tragic misrepresentation.

A HISTORY OF HUMAN USE AND WILD HERDS INTERMINGLED

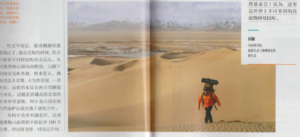

The nominated area is as big as Denmark and Netherlands combined, 75,000 sq. kms used as seasonal pasture by Tibetan livestock producers for millennia, their ongoing, skilful, sustainable and productive land use ending only in very recent years, due to their compulsory removal by state power relocating them to lead useless lives in concrete camps positioned along the highway to Lhasa, just outside of the petrochemical city of Gormo, far north of their ancestral pastures.

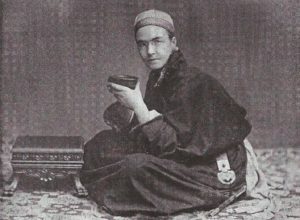

The Tibetan communities who seasonally pasture their yaks and sheep, alongside the migratory tsö, the Tibetan antelope (pantholops hodgsonii, widely called chiru), move their herds in summer, when monsoon rains bring grasses to flourish, know this land intimately. Back in 1898 a Canadian missionary traversing Kokoshili en route to Lhasa described how she found her way through snowstorms by looking for the lhatse cairns of stones at each pass across the hills, sacred sites dedicated to the local deity protectors of the land, to whom Tibetan travellers always make offerings. What Dr. Susie Rijnhart experienced in 1896 is true today, but many of the nomads have now been relocated, without choice, north to the heavy industrial city of Gormo, where they were inspected by Xi Jinping in August 2016.

Canadian missionary Susie Rijnhart found Tibetan drogpa nomads, with their yak herds, living in Kokoshili, as in all other areas of Tibet, pasturing their animals: “Suddenly we saw some white tents, and on nearer approach discovered there were fourteen of the m, having about 1500 yak and many horses. We were received in a very friendly manner by the travellers, most of them knowing us. Though they wanted us to camp beside them, we went on to ford the waters. The sensation of camping across the river from friends was peculiar. The tents on the opposite bank looked like a town, but in the morning every vestige of the recent inhabitants with dwellings was gone, and we were again alone.” [1] Kokoshili –and all Tibet- was a land without fences, in which wild and domestic herds mingled unhindered, and wild animals seldom feared human presence.

m, having about 1500 yak and many horses. We were received in a very friendly manner by the travellers, most of them knowing us. Though they wanted us to camp beside them, we went on to ford the waters. The sensation of camping across the river from friends was peculiar. The tents on the opposite bank looked like a town, but in the morning every vestige of the recent inhabitants with dwellings was gone, and we were again alone.” [1] Kokoshili –and all Tibet- was a land without fences, in which wild and domestic herds mingled unhindered, and wild animals seldom feared human presence.

MAKING A NO-MAN’S LAND: A 21st CENTURY TRAGEDY

Now, the antelopes are starting to come back, but many of the nomads are gone. The state has taken over, erasing almost all memory of community conservation effort, other than ritually honouring the martyr Sonam Dargye, who, in death has become China’s Soinam or Suonam Darje. All else is veiled by official amnesia, as if it never happened.

The Tibetans foresaw what would happen. In a debate almost 20 years ago, in the remote village of Sokya (Suojia in Chinese), inside the proposed Kokoshili World Heritage site the local pastoralists debated the future with Tador, the first son of Sokya to get a university education, who had returned to his village as local party secretary. As journalist Liu Jianqiang tells it: “There was no medical service, no highways nor electricity. Suojia was caught in the middle of a net formed by the four big rivers of Mochu, Yamchu, Damchu and Jichu. Half the year, water isolated it from the outside world. ‘Wild ass and marmot are our specialities’ Tador replied. ‘We’ve got no minerals and no caterpillar fungus [for income]. Our cattle can’t be shipped out. Therefore in Suojia -including Kokoshili- our only specialty is wild animals.’ Wild and rare animals are abundant in Suojia: Tibetan antelopes, snow leopards, Tibetan wild ass, black-necked cranes. Tador said, ‘We can establish wild animal zoos here just like in Africa. Our country may not care for us, but may care for the animals. When it’s time to care for the animals, they will have to care for us. If we successfully protect Suojia, they will invest to solve our livelihood issues when the government establishes nature reserves. Party Secretary Sonam [Dargye] was sacrificed for the protection of Tibetan antelopes. We’ll continue his work.’” [2]

Successive Tibetans persisted in this difficult work, sometimes as local government officials, sometimes by setting up the first ever Tibetan environmental NGOs, sometimes with support from international NGOs from Hong Kong, Europe and the US, including Conservation International.

What these farsighted Tibetans did not expect was that, in the name of watershed management and growing more grass, many would be resettled far from home on the fringes of an industrial city, with no vocational education enabling entry into the industrial economy, no access to ancestral land, no mobility and no use for their deep understanding of how to live and thrive in a water meadow land of lakes ideal for yaks, sheep and horses, in which jeeps only bog.  While the displaced nomads are reduced to dependence on state rations, in new concrete settlements, their lands are now solely governed by a sovereign state that has never understood or appreciated this vast landscape of frozen lakes in winter and permafrost summer melt into wetland and water meadow.

While the displaced nomads are reduced to dependence on state rations, in new concrete settlements, their lands are now solely governed by a sovereign state that has never understood or appreciated this vast landscape of frozen lakes in winter and permafrost summer melt into wetland and water meadow.

REINVENTING SAFARI TOURISM FOR CHINA’S MASSES

China argues that this is a wilderness, a “no-man’s land” ripe for modernity, specifically for mass domestic tourism based on the romance of being the first humans to conquer “no-man’s land”.

This “

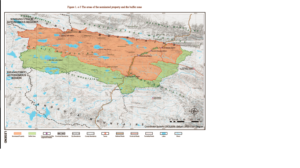

This “ untouched” wilderness in fact has running right through it, for 250 kms, the Qinghai-Tibet Engineering Corridor (QTEC), as China proudly calls it, a corridor of highways, railways, oil pipelines, optical fibre cabling and ultra-high voltage power grid, from north to south. The portion designated to become World Heritage, far from being remote, has not only a 250 kms engineering corridor through it, but also 13 railway stations built solely as viewing platforms to take iconic shots of iconic species, if the train stops for a photo opportunity. As the antelopes flee, the train seldom stops at these desolate platforms.

untouched” wilderness in fact has running right through it, for 250 kms, the Qinghai-Tibet Engineering Corridor (QTEC), as China proudly calls it, a corridor of highways, railways, oil pipelines, optical fibre cabling and ultra-high voltage power grid, from north to south. The portion designated to become World Heritage, far from being remote, has not only a 250 kms engineering corridor through it, but also 13 railway stations built solely as viewing platforms to take iconic shots of iconic species, if the train stops for a photo opportunity. As the antelopes flee, the train seldom stops at these desolate platforms.

The boundaries drawn by China’s nomination to UNESCO place this QTEC in the middle of the designated property. China has no wildlife adventure safari trekking tourism yet, but that is the plan.

The wild migratory antelope herds must cross QTEC, especially the pregnant females seeking the safety of remote birthing grounds where there are few predators. The high embankments built to keep the railway line temperature stable are a major barrier.

The wild migratory antelope herds must cross QTEC, especially the pregnant females seeking the safety of remote birthing grounds where there are few predators. The high embankments built to keep the railway line temperature stable are a major barrier.

While China’s nomination denies all human presence, it focuses strongly on the tsö antelopes, as if the biodiversity conservation of this iconic species was the entire purpose of seeking World Heritage status. Some key questions: what is China’s record so far on conserving this highly migratory species? What has been the role of Tibetan communities of livestock herders in protecting the tsö over the centuries, and right up to this century? Who has stronger motivation to conserve both biodiversity and habitat: the state or the communities?

WILL WORLD HERITAGE PROTECT HABITAT?

The logic of China’s mapping, placing the engineering corridor front and centre, has nothing to do with effective habitat protection, which would require a bigger area, in three provinces.

The habitat of the tsö/chiru/pantholops hodgsonii covers a much bigger area than China’s proposal, which is restricted to the province of Qinghai. The antelopes know no provincial boundaries, ranging freely, by season, across three provinces, wintering in Qinghai and Tibet Autonomous Region, migrating north into the Arjin Shan mountains of Xinjiang each summer to give birth and care for their young, far from wolves and snow leopards. The birthing grounds are so remote that wildlife biologists only discovered their location this century.

The mapping of the proposed World Heritage area excludes a massive cobalt deposit.[3]

IN CHINA’S TIBET, WHO SLAUGHTERED THE ANTELOPES?

The decline from one million of the agile, highly mobile tsö antelopes, down to as few as 65,000 in the 1990s, happened entirely in the years of China’s rule, since the 1950s. Chinese soldiers, stationed across Tibet to quell uprisings, bored, underfed and isolated, shot antelopes from their jeeps. Tibetans were powerless to stop them.

In the 1980s, with the opening up of China, this frontier zone experienced a gold rush, as thousands of poor Chinese Muslims poured across the river beds of this “no-man’s land” seeking flecks of alluvial gold. Again, there was little the Tibetans could do to stop them, as local county governments encouraged them, or were paid off to look away.

The gold miners hunted the antelopes, just for their downy underbelly fur, to be sold illegally for the manufacture of superlight shahtoosh luxury shawls. Kokoshili was a wild west, beyond the frontier, where the desperate and the ruthless could take what they wanted, and the rule of law was absent. Kokoshili had become “the playing field of bandits, ruffians and gangsters. Gangsters illegally occupied large tracts of land. Then they sent out rumours the land was full of gold, selling fake licences to the peasants, charging each five hundred yuan. If anyone refused to pay, they would be killed to set an example for the others.”[4]

The gold miners hunted the antelopes, just for their downy underbelly fur, to be sold illegally for the manufacture of superlight shahtoosh luxury shawls. Kokoshili was a wild west, beyond the frontier, where the desperate and the ruthless could take what they wanted, and the rule of law was absent. Kokoshili had become “the playing field of bandits, ruffians and gangsters. Gangsters illegally occupied large tracts of land. Then they sent out rumours the land was full of gold, selling fake licences to the peasants, charging each five hundred yuan. If anyone refused to pay, they would be killed to set an example for the others.”[4]

It was only in the 1990s that a small bunch of Tibetans based in Drito, distressed at the slaughter, formed a posse to hunt the hunters. Although they were determined to confront the Chinese Muslim miner/hunters, what legal authority did they have? The rangers were based in Drito just east of Kokoshili, a county (and town) whose Tibetan name means source of the Yangtze River (Dri Chu in Tibetan). Kokoshili, to the west, was where they had always taken their herds in summer, when the rains filled the many lakes and rivers, grass grows abundantly, and the nomads know how to live skilfully off uncertainty in a marginal environment. For most of the year, Kokoshili is not only dry but very cold, with permafrost freezing what moisture remains in the soils of this land of lakes and riverheads. Summer brings not only monsoon rains, but melts the permafrost, making many areas boggy. Only the skilled, experienced nomads can navigate this land.

Kokoshili is so remote and, in Chinese eyes, so unattractive, it was not even designated as a county, despite its size. By default it was technically administered by the distant industrial city of Gormo and the even further distant provincial capital of Xining. In the official gaze of the state, it was a blank, a lacuna, where jeeps sink into bogs, conquerable only by massive investments, such as a railway raised high above the plain on embankments and bridges for its entire transit.

The antelopes faced a short path to extinction, which local Tibetan communities were helpless to prevent, despite thousands of years of wild and domestic herds intermingling, as nomads took their sheep, goats and yaks into Kokoshili every summer to graze. Then in the 1990s, a miracle happened: the Tibetans on the eastern fringes of Kokoshili mobilised, inspiring a worldwide movement of environmentalists inspired by the heroism of the Tibetan rangers, successfully halting and reversing the slide to extinction. That is the story of the next blog.

[1] Susie C. Rijnhart, With the Tibetans in tent and temple,1904, 241 online via: https://archive.org/details/withtibetansinte00rijn

[2] Liu Jianqiang, Tibetan Environmentalists in China, Lexington, 2015, 222

[3] Chengyou Feng,, Wenjun Qu, Dequan Zhang, Re–Os dating of pyrite from the Tuolugou stratabound Co(Au) deposit, eastern Kunlun Orogenic Belt, northwestern China, Ore Geology Reviews 36 (2009) 213–220

[4] Liu Jianqiang, Tibetan Environmentalists in China, Lexington, 2015, 96