MINING TIBETAN GOLD, MINING BEIJING’S PATRIOTIC SUBSIDIES

Chinese announcements of mineral bonanzas under the Tibetan surface have been made for decades, but in only a few areas has this led to mining.

Now, in remote Lhuntse county, well to the southeast of Lhasa, we are told of the latest treasure, although the South China Morning Post story is remarkably vague as to what the metals are.

Why does Lhuntse suddenly burst into the news; in turn prompting a swift rebuttal, also in English, from the punchy CCP mouthpiece Global Times? Location, location, location. There are only two places where the borders of India, Bhutan and China meet. One is Doklam in Bhutan’s mountainous west, scene of a protracted and tense standoff between Chinese and Indian forces, now seemingly defused but with none of the underlying issues resolved. The other trilateral intersection is Lhuntse, on Bhutan’s mountainous eastern border with the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh and Tibet Lhoka Lhuntse.

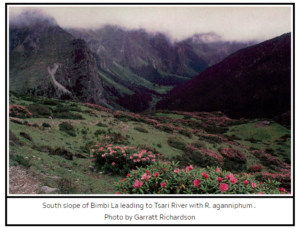

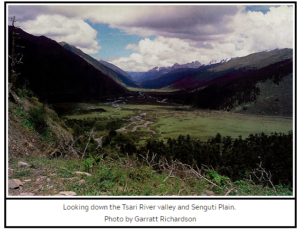

To Tibetans, Lhuntse is special for very different reasons, as the entry to the sacred pilgrimage of the crystal mountain of Tsari, not as well known globally as Kailash/Gang Rinpoche or Amnye Machen, but just as revered for its ability to bestow blessings and deep insights into the nature of reality.[1] Traditionally, many Bhutanese did the Tsari pilgrimage too.

Now, we are told, there are billions of dollars of valuable minerals awaiting imminent extraction in this remote, mountainous county of southern Tibet. We might just as well say there are billions of dollars’ worth of valuable minerals below the street where you live; both statements are equally true yet utterly meaningless.

Such claims rest on basic misunderstandings of the intersections of geology and economics. The entire planet is made of valuable minerals, which occur everywhere. Some are naturally rare, such as the well-named family of rare earths, meaning that even in a highly concentrated deposits, only a tiny fraction is the sought after elements. Other elements, such as lithium or silicon are very common.

What distinguishes a mineral deposit is an unusual concentration, usually due to unusual circumstances that arose many millions of years ago, deep underground. But a deposit is not a mine. Even if a deposit is laboriously mapped in all three dimensions, so its shape and mineral concentrations are known with some precision, there are still innumerable hurdles before a deposit (or more basically, a reserve) becomes a mine. It is easy for geologists to claim to have found great riches, to elicit congratulations. But in a globalised commodity chain economy, any deposit must then pass several more tests.

If one looks at where mining actually happens, especially large-scale mining, huge sums of capital were poured into that specific location on the basis of careful calculations that the mine will steadily produce a certain tonnage, at a certain cost of extraction, which must be considerably lower than the assumed selling price to those who generate demand for that mineral after it has not only been extracted but concentrated and smelted into something pure, for industrial use.

The business case for any mine must weigh many variables, and many assumptions, some of which usually turn out wrong, because who can tell what will be the price of oil, or iron ore, or lithium ten years from now? But a big underground mine can easily swallow capital expenditure by investors for a decade before it starts producing ores and profits. That is a major reason why mining has such booms and busts: the lead time is beyond our ability to calculate risk.

A mineral deposit in Tibet must add other considerations that make mining expensive. Roads and railways are few, prone to landslides, earthquakes, permafrost heaving and slumping, with vast distances to haul in equipment and haul out the minerals. It’s a long way to market, especially for minerals used mostly by industries in coastal China, which have as a ready alternative buying the same minerals from abroad, or buying a mine in Peru or Congo or Australia, even cornering the global market.

These are among the obstacles facing any proposal to extract from Tibet. Further obstacles arise if the commercially valuable mineral, even in a highly concentrated deposit, is still only a small proportion of the total rock. That means it must be processed on the spot; it makes no sense to haul raw ores thousands of kilometres to a distant smelter. This may not matter in the case of oil, coal, iron ore or chromium, which may be pure enough as they come out of the ground to just haul away for distant processing. It doesn’t apply to alluvial gold, sitting as specks or nuggets in riverbeds, already pure. But most of the big deposits discovered in Tibet, across a very wide area, in the last three decades are polymetallic, containing several metals, usually copper, molybdenum, gold and silver, which at least need concentration if not smelting before shipment. That in turn means a substantial investment in the equipment needed to crush rock to powder and then cook it chemically to get rid of most of the waste. That requires a lot of expensive equipment, a substantial workforce skilled in industrial methods, urban infrastructure, a reliable power supply, and heavy freight transport to a smelter. None of these can be assumed to exist in the usually remote districts where the minerals are found, as Tibet is the size of Western Europe. A newly discovered deposit on the German border with Poland would not readily be considered economic just because there is already a smelter in Spain.

To this day, the only mineral extracted from Tibet Autonomous Region that is recorded in official statistical year books is chromium, an industry now in steady decline, with production for 2016 listed as 67,000 tons, which is a return to the levels of the late 1980s, from a 2010 peak of 201,000 tons.

Perhaps it is no surprise that gold is nowhere mentioned officially since much of the production was small-scale, artisanal, and highly destructive of pastoral and riverine landscapes. It may be that the copper, gold and silver extracted from Shetongmon, near Shigatse, are recorded (if anywhere) in Gansu statistics, as the concentrate is sent by rail to a smelter in Gansu. But what about the other copper mines, for example, upstream from Lhasa? Deposits are many, mines are routinely announced, then very little happens. When mining does occur, deposits are often parcelled out to various competing local interests all with claims as stakeholders, restricting mining to low tech extraction on a modest scale. Time after time, the headline announcements of massive deposits result in very little.

But very little, in terms of tonnage extracted, can be highly damaging environmentally, and Tibetan communities are usually quite upset at the intrusion by immigrants who care naught for local habitat or community. However this is far from the bonanza in the Himalayas that predictably presses the buttons of India’s geostrategists, ever alert for the latest Chinese threat.

In the most recent available official statistics, Lhuntse county is listed as having a rural population of farmers and pastoralists (rural labourers in official classification) of 18,000 in 2016, counting those officially registered as resident, not immigrant. Of those, 6490 were registered as agriculture and livestock producers, while only 250 worked in industry, including mining, suggesting an economy that employs very few Tibetans. A further 9560 –half the entire work force- were registered as working in construction, suggesting an economy based on recruiting much manual labour for urban construction.[2] In the 2000 Census, Lhuntse dzong had a population of just over 32,000, of whom 98.7 per cent were Tibetan. That, of course, does not include the garrison of PLA troops on border duty.

All this, the SCMP excitedly tells us, has changed dramatically since 2016, with an immigrant rush that has set up restaurants, “a hair salon, laundry service, supermarket, cosmetics store, Western-style bakery, confectionery shop and bars. After nightfall, the bars and barbecue stands are filled with the sound of people speaking dialects from across China. They are miners and labourers, but they are also sleek salesmen and investors dressed in suits and shiny shoes. A woman who runs a laundry service said she had about 30 to 40 customers a day, and although dry cleaning was expensive, that did not seem to bother her regulars.”

But what is actually being mined? “Enormous, deep tunnels have been dug into the mountains along the military confrontation line, allowing thousands of tonnes of ore to be loaded and transported out by trucks daily, along roads built through every village. Extensive power lines and communication networks have been established, while construction is under way on an airport that can handle passenger jets.”

Ok, but what are those ores? What is it that will make Lhuntse’s fortune? This lengthy story does not quite say. It does name the mining company, Tibet Huayu, which in its filings with Shanghai Stock Exchange, where its shares are traded, defines itself as focused on lead, zinc and antimony, metals found abundantly in many Tibetan areas, metals which are seldom worth recovering unless they are classified as incidental by-products of mines with more valuable metals, usually copper, gold and silver. Even then, the on-site processing extracts only concentrates of copper, silver and gold, and usually dumps the lead and zinc in the mine waste tailings, along with a massive tonnage of uneconomic rock. This is both wasteful and toxic, as lead is highly poisonous and if it leaches into rivers causes serious damage to animals and people.

The photos accompanying the article give us some clues. We don’t see the “enormous, deep tunnels”, just drill rigs dotting a hillside, and the interior of a large shed, with machinery whirring away, driven by rubber belts, suggesting a small stamping mill to crush rock. Not much to get excited about.

There are a few clues in the SCMP story as to what this is all about. “Weng Qingzhen, who owns a Sichuan restaurant in the county, said she moved there less than two months ago after friends and relatives told her about the mining boom. “We came here for the gold rush, but this place is not as wild as I thought,” she said.”

A vein of gold explains a lot. Many Tibetan deposits of copper, lead and zinc, or copper and molybdenum also have gold and silver, and sometimes the gold is concentrated in a skarn cap on the top of the deposit, as it slowly formed over millions of years as molten magma deep underground very slowly cooled, and in the presence of superheated water, gradually separated the elements.

A vein of gold atop a deposit of lead and zinc explains the small-scale stamping mill, the  underground tunnels, the trucks taking ores to some distant place where the gold can be smelted. This is not gold rush as metaphor, the gold is there.

underground tunnels, the trucks taking ores to some distant place where the gold can be smelted. This is not gold rush as metaphor, the gold is there.

Gold rushes usually are quickly exhausted, and the hair salons and bars (euphemisms for brothels) move on. What is left behind is the dumps of rock waste, on sloping land above the rivers that form the Subansiri River of northeastern India. That’s a real concern.

Lhuntse’s many rivers are transboundary, flowing into India and eventually into the Brahmaputra. The Nyel Chu, Jar Chu, Tsari Chu and Loro Chu all rise within the hook of the great bend of the Yarlung Tsangpo/Brahmaputra to the north, comprising the headwaters of India’s Subansiri. The hydropower potential of the upper Subansiri has been plotted and planned for decades, plans which would be seriously compromised if toxic heavy metals come down river from abandoned tailings dams in Lhuntse.

The SCMP story predicably got India’s security state pundits wagging. It stoked, yet again, Tibetan fears of the Chinese juggernaut. Unlike the SCMP’s blander print headline, its’ online headline no doubt intended this: How Chinese mining in the Himalayas may create a new military flashpoint with India.

Is this patriotic fervour just the overexcited imagination of a reporter? Unlikely. Is it SCMP, now owned by Jack Ma’s Alibaba, out to prove its loyalty to Xi Jinping’s new era? Perhaps. The likeliest explanation for this flimsy provocation is that it was engineered by Tibet Huayu Mining, seeking to place itself on the frontline of China’s reconquest of Arunachal, fortified by Huayu’s success in bringing Chinese enterprise and Chinese immigrants to a remote border town. A key line in the SCMP story: “The new mining activities would lead to a rapid and significant increase in the Chinese population in the Himalayas, which would provide stable, long-term support for any diplomatic or military operations aimed at gradually driving Indian forces out of territory claimed by China.”

Why would Huayu place such a story? Is it because, in an authoritarian system, conspicuous obedience to the official line is the key to success? Of course, but that’s not the whole story. Huayu has specific reasons to be super patriotic. Huayu was incorporated in 2002, with its’ head office at Huayu Building, Gesang Road, Lhasa. It is highly profitable, even though it does little mining, and the minerals it specialises in –zinc and lead- are regarded by bigger miners as not worth bothering with in Tibet. In 2018 Huayu entered into a business deal with an exploration company to do work an experienced miner with 16 years’ experience would normally have in-house. How come a mining company does not have its own exploration division?

The answer appears to be that what Huayu does mine is not only minerals but subsidies. It all starts with making Lhasa the corporate headquarters, and putting Tibet in the company’s name. That alone entitles it to lots of incentives, subsidies and tax breaks, just for setting up shop on Gesang Road.

Early in 2018 Huayu forecast that its 2017 profit would be sharply up from 2016, explaining that: “The reasons for the forecast are sharply increased main product and contribution from government subsidy.”[3]

The choice of a frontier county which has never, until very recently, had many Chinese immigrants, was an investment in patriotism. That attracted state support, including installation of power grid extensions, road building and other urban services. An airport is under construction.

But Tibet Huayu has bigger plans, and bigger subsidies to attract. It has recently bought half ownership of a Tajikistan gold mine from a state-owned Tajik Aluminium corporation,TALCO.[4] This places Huayu at the forefront of China’s Eurasian Belt and Road, a mix of patriotism and profit, and Huayu is not shy about it. It reminds its shareholders that: “As the national “One Belt and One Road” policy continues to advance in Central Asia, the company is located in countries along it.”[5]

Being based in Lhasa, the TAR government has provided support for Huayu’s westward thrust into Tajikistan: “the company has actively promoted the overseas equity investment projects and successively obtained the Ministry of Commerce of the Tibet Autonomous Region Certificate of Overseas Investment of an Enterprise and “Project Filing Notice” issued by Tibet Development and Reform Commission.” That is what Huayu filed in one of its regular updates for its investors on the Shanghai Stock exchange.[6] This entitles it to further incentives and tax breaks.

Patriotism is good for business. Huayu –its name means Chinese language- is adroit in positioning itself at the forefront of China’s great rejuvenation, be it in Lhoka Lhuntse or Tajikistan. It is equally adroit at assuring central leaders that its intensive exploitation of gold at Lhuntse in no way contradicts the wider policy of classifying Tibet as a strategic reserve of mineral resources to be mined not now but some time in the future. The rhetoric has changed. SCMP: “The Lhunze mining boom would not be expanded to other areas. In other parts of Tibet, mining activities have been prohibited or strictly limited because large-scale excavation and processing of minerals could produce excessive waste chemicals and debris, posing a threat to the fragile Himalayan environment and potentially causing irreparable damage to the natural landscape.”

With remarkable promptness, the SCMP Lhuntse story was repudiated one day later by party organ Global Times, a medium seldom outdone in loud patriotism. What Global Times repudiated was not anything about Huayu’s Lhuntse operation, but that this constitutes a springboard for retaking Arunachal from India. That, Global Times assured us, is “groundless hype.”[7]

Thus the news cycle completed, only to be taken up in India, and by Tibetan exiles.

What we find in these two stories is sophisticated PR and news management, from Huayu in placing the SCMP story, wrapping themselves in patriotic hype, and in Global Times prompt quashing of the slightest suggestion that China is aiming at repeating its 1962 conquest of Arunachal, at a time when China does not want to drive India into the arms of a Quadrilateral of countries aiming to contain China. What starts in English, on SCMP, stays in English, on Global Times. The last thing central leaders want is a patriotic wave within China demanding the reconquest of Arunachal.

We must learn to read between the lines. These days, the lines are written by authoritarians. We all know that in an authoritarian system, those in authority bark orders are subordinates. We sometimes forget that those who bark also submit to higher authority, and an authoritarian system rewards those who know both how to bark and how to submit. Huayu is a corporation for such times.

[1] Toni Huber, The Cult of Pure Crystal Mountain: Popular Pilgrimage and Visionary Landscape in Southeast Tibet, Oxford, 1999

[2] TAR Statistical Yearbook 2017, Table 17-1: Main economic indicators by county.

[3] Tibet Huayu Mining sees FY 2017 net profit up 52.27 pct to 70.97 pct, Reuters, 25 Jan 2018

[4] Tibet Huayu Mining Co Ltd: Says It Signs Jv Agreement With State Unitary Enterprise Tajik Aluminium Co Tajikistan Regarding Talco Gold Mine, Reuters, 18 December 2017

[5] Tibet Huayu Mining, Announcement on the Progress of Overseas Equity Investment Projects http://static.sse.com.cn/disclosure/listedinfo/announcement/c/2018-05-19/601020_20180519_12.pdf

[6] Tibet Huayu Mining, Announcement on the Progress of Overseas Equity Investment Projects http://static.sse.com.cn/disclosure/listedinfo/announcement/c/2018-05-19/601020_20180519_12.pdf

[7] Deng Xiaoci, Himalayan mining reports groundless hype: analysts:Global Times 2018/5/21 http://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1103380.shtml