BIODIVERSITY, ETHNIC DIVERSITY: CAN YOU HAVE BOTH?

A new urgency about effective action on climate change is evident wherever you look, from striking school children marching on city streets, to the endless torrent of scary warnings from panels of scientists. The 2015 Paris agreement, which let each country set its own climate change targets, already looks tired and inadequate.

Loss of biodiversity worldwide has also been gaining a similar urgency, report after report tells us a million species are at risk of extinction. Human dominance of the entire planet, at the cost of all living beings, is more questionable than ever.

The build-up to each global treaty negotiation on climate is intense; likewise the build-up, now counting down, to a renewed treaty commitment by every nation on earth, to act effectively to protect life, all species, all of global biodiversity. That build-up culminates in October 2020, when all nations convene, at the foot of the Tibetan Plateau, in Kunming, for the Conference of Parties (COP15) of the UN Convention on Biodiversity (CBD).

VOICE OF THE VOICELESS

The staging of this crucial gathering in Yunnan Kunming, where China can decide who to allow in and whom to exclude, greatly complicates the issue.

Kunming, in October 2020 will be the culmination of years of advocacy for those who have no human voice, the wildlife of the world, including the millions of species almost completely unknown even to scientists. The prospect that we could almost casually, inadvertently make extinct so many species, not just the iconic mammals, in the name of efficiency, productivity and a globalised commodity food supply chain, is galvanising wildlife campaigners worldwide. Momentum is building.

Expect intense debate. Paris, an open city, had plenty of public spheres for the urgency of the climate debate to be aired in 2015. Kunming, however, although well situated in one of the world’s greatest biodiversity “hotspots”, is in China, where open debate, on anything, is tightly controlled. But, in the UN system, it was China’s turn.

The last time CBD declared a target for protected areas, meant to be binding on all governments, was back in 2010, known as the Aichi Target, aiming at each country setting aside 17 per cent of its territorial area for the protection of wildlife. At Kunming 2020 that Aichi target will be hotly debated, critiqued as inadequate, with demands that it be upped to as much as half the land surface of each country.[1] No wonder many governments will resist, and instead propose no mandatory target, merely those “voluntary commitments”, in UN jargon INDCs, Intended Nationally Determined Contributions.

By October 2020 the high speed railway from Kunming to Shangri-la (Dechen in Tibetan, Xiang er li la in Chinese), via Dali and Lijiang will be operational, enabling delegates a quick mid conference excursion to Tibet, including a bridge over Tiger Leaping Gorge, due to soon be dammed for hydropower, despite UNESCO’s feeble objections to damaging a World Heritage property.

ARDUOUSLY CONSTRUCTING ECOLOGICAL CIVILISATION

China plans the 2020 Kunming event as a celebration of China’s exemplary prowess as conserver of wildlife, announcing it has met the Aichi Target of 17 per cent of its territory set aside for wildlife conservation, by declaring as much as 30 per cent of the entire Tibetan Plateau to be National Parks. It will be a triumph. That national park system, with four of the ten new Chinese parks, and by far the biggest, situated in Tibet. They are due for official launch months before the Kunming conference. Yet again, China leads the world in constructing “ecological civilisation” 生态文明思想.

If ecological civilisation sounds a bit odd in English, it is. In new era Chinese usage, pristine landscapes for wildlife (and carbon capture and water provision for distant consumers and much more) don’t just happen, they must be constructed. Only the power of the state, the epitome of civilisation, can do this. That is because it is an “arduous task”, to use another CCP jargon, which only state power can allocate funding and commit all citizens to; and only a state can carefully plan with scientific precision how to make a pristine natural wilderness.

If that still sounds odd, it doesn’t in China, where concepts such as rebuilding an authentic replica Potala makes sense, as does the strenuous state-directed project of building ecological civilisation.

SIGNIFICANCE OF KUNMING

Why Kunming? It was clear in recent years it was China’s turn to stage the CBD in 2020, and it seemed Beijing was the location. The switch to Kunming, in China’s subtropical southwest, signals a new spectacular, staging the event in China’s biodiversity hub. The Pota Tso (Pudacuo in Chinese) protected area, just upgraded to National Park, is conveniently nearby to showcase pristine wetlands.

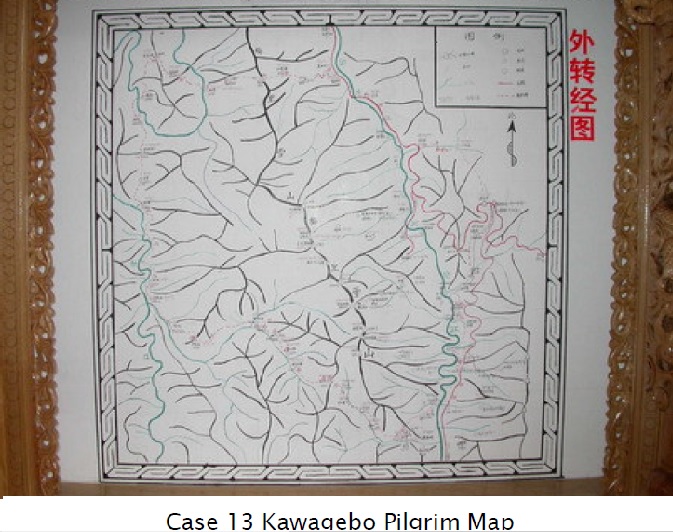

Tibet is tantalisingly close; in fact Kham Gyalthang is now officially the Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture of Shangri-la, comprising the upland portion of Yunnan province, featuring famous sacred sites such as the Khawa Karpo (Meili Snow Mountain) holy pilgrimage circuit, and the UNESCO World Heritage Three Parallel Rivers protected area.

It is the large Tibetan prefecture of Yunnan that gives Kunming its cred as global capital of biodiversity. China expects to be congratulated as the exemplary leader of the entire developing world, a model to be emulated. China intends CBD COP15 in Kunming to be its coronation as conservation central.

The world yearns for a good news story, at a time when leadership on climate and wildlife is not coming from the US, Europe is divided, and the American presidential election is only a month after the Kunming event. China will control the narrative, alternative voices will be blocked from attending, and there will be plenty of celebs and top influencers at hand to amplify China’s pride.

OFFICIAL AMNESIA

Those alternative voices could tell us there is another side to the straight arrow narrative of China’s ascendancy as the greatest ecological civilisation. Mandatory amnesia is now common in today’s China, especially when it means forgetting past state failures incompatible with today’s state ambitions. China’s new era narrative rewrites recent history, in several ways, erasing living memories in order to insert the state as the sole actor, sole protector of wildlife and biodiversity.

In the interests of homage to all protectors, and the value of memory, we correct the record, with five key remembrances that add up to an alternative path for the future of Tibetan wild life and livelihoods::

- For years China wrestled with the actual Tibetan “hotspot” location of greatest biodiversity, only to turn elsewhere, for fear of fanning pan Tibetan unity.

- China remains the world’s biggest market for animal parts from around the world, providing the finance incentivising hunters, poachers, smugglers and criminal networks all focussed on the insatiable demand in China for supposedly curative animal parts accursed by the Chinese characteristics attributed to them.

- Kunming was for decades a centre not only of biodiversity but of the indigenous knowledges, of many minority ethnicities, which had effectively protected biodiversity for thousands of years. Today’s China, in order to make the state the sole actor and sole protector of wildlife not only shut down the hugely successful Kunming Centre for Biodiversity and Indigenous Knowledge, but erased its remembrance.

- Kunming was for decades the centre of a global network of endangered species research, inclusive development projects bringing together international donors and local communities as equal partners. Not only has this effort been closed, its memory has been suppressed.

- Tibetans were deeply engaged in these initiatives, in risking –and losing- their lives to protect wildlife at a time when central leaders had no concern for the wild west of upper Tibet, beyond the frontier, where cruel poachers and rapacious miners roamed at will. Those shameful decades of the 1980s and 90s are also expunged from the new story of the deep, longstanding, heartfelt and benevolent care extended by the central state to the remotest alpine deserts of Tibet. Today, when Tibetans speak up to protect local environment, they are criminalised, with heavy jail sentences.

KHAM: HOTSPOT WITH THE LOT

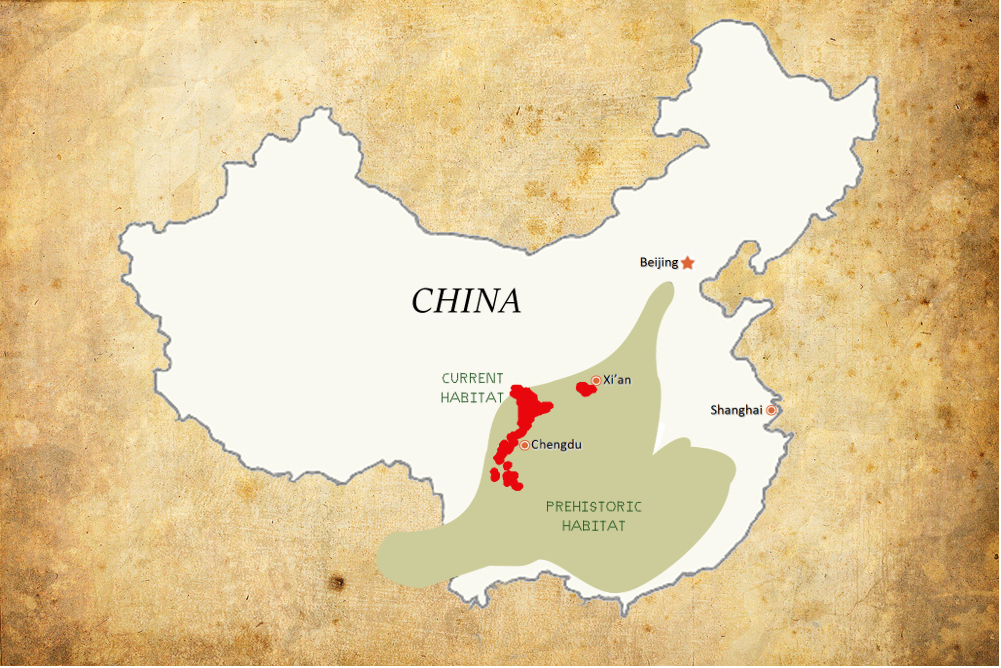

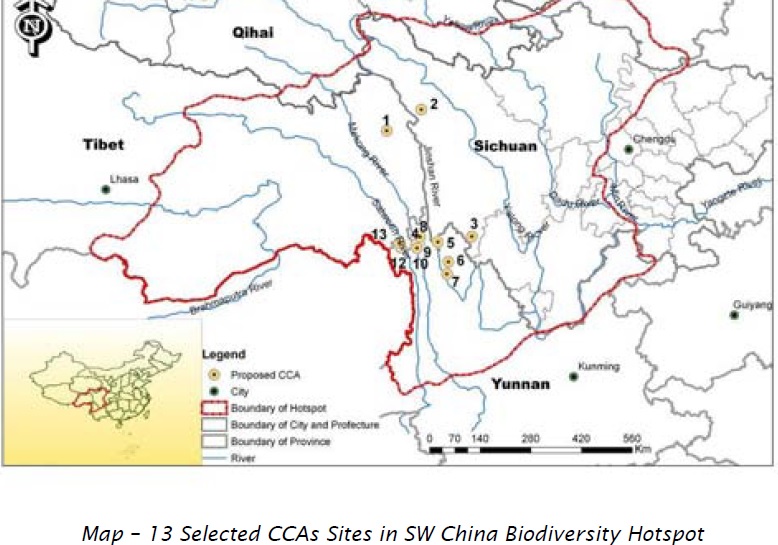

First, Kunming is indeed on the fringe of a great biodiversity hotspot, so big the moniker “hotspot” is misleading understatement. This is Kham, or eastern Tibet. Politically, Kham is carved up into no less than four Chinese provinces: Yunnan Shangri-la; Sichuan, Qinghai and Tibet Autonomous Region.

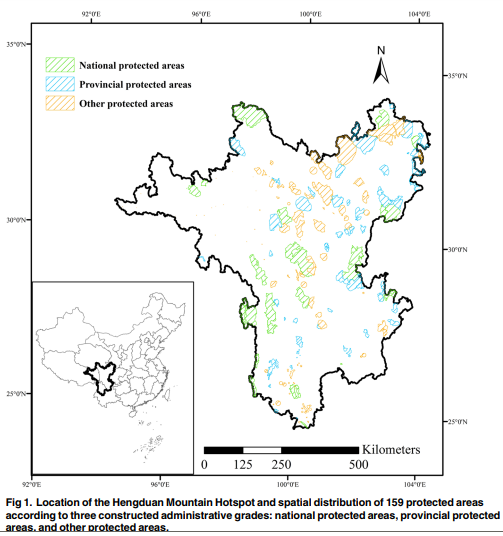

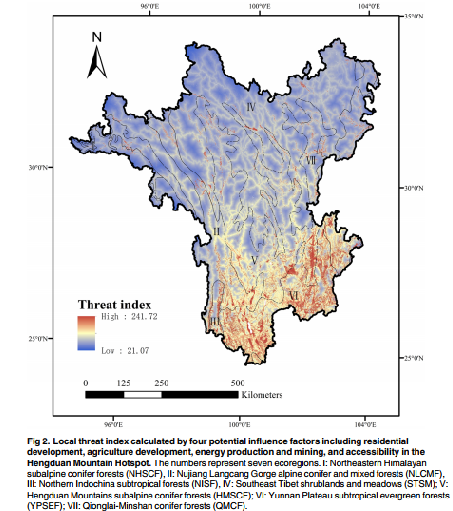

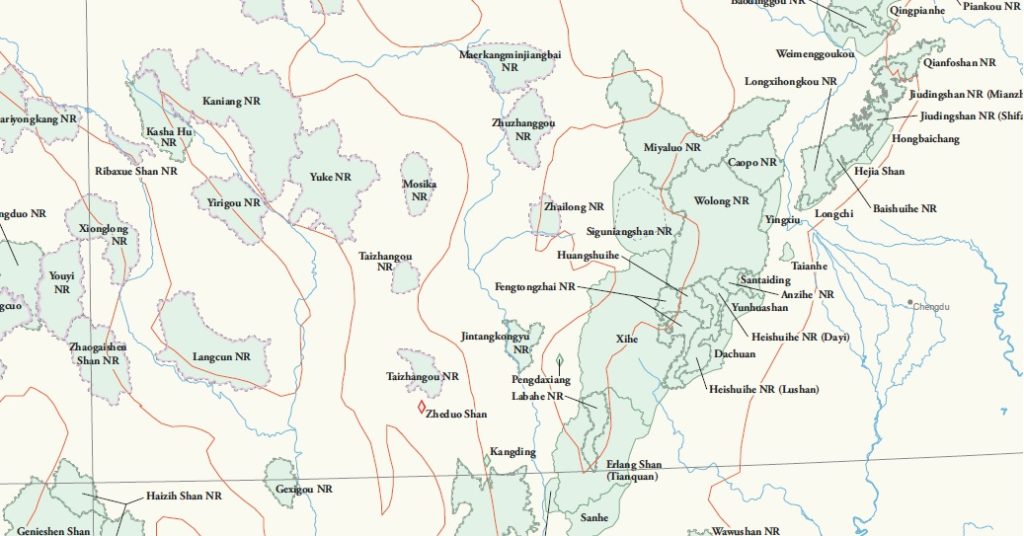

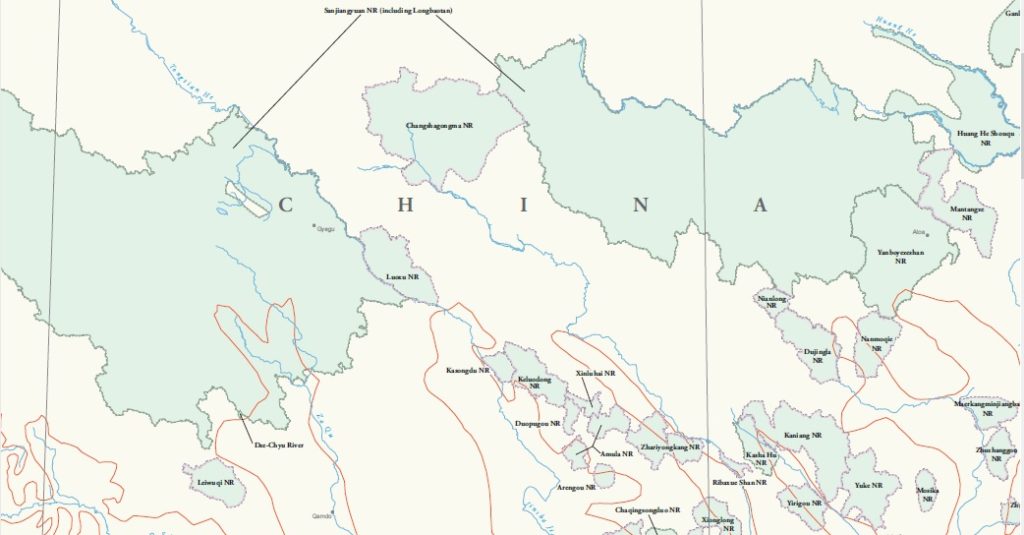

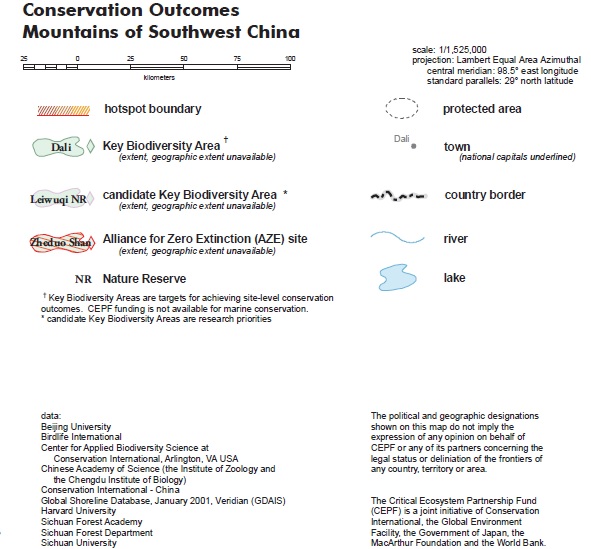

Kham is the dramatic end result of India tectonically pushing into Eurasia, a deeply crumpled, rugged landscape of endless mountain ranges dissected by the deep valleys of great wild rivers. Precipitous Kham, to use a classic Tibetan phrase, in its ranges and rivers, provides habitats from the subtropical to the alpine, on every slope. That is what makes it such a biodiversity hotspot, first named as such by the global NGO Conservation International, decades ago. They called it the Hengduan Mountains, or Southwest Mountains of China hotspot.

Kham is the wettest and warmest part of the Tibetan Plateau, able to sustain an extraordinary variety of life. The enormity of this biodiversity “hotspot” is the story China doesn’t want you to know. That is because the new National Parks spread across the Tibetan Plateau are mostly not in the hotspot, but in areas of lesser biodiversity, which happen to be the sources of lowland China’s water supply. The newly declared protected areas, and the areas of greatest diversity of life don’t match up. China doesn’t tell you this, nor does Conservation International, which discovered, after years of advocacy, that China had no interest at all in creating a pan Tibetan entity that would unite all the provinces into which the Tibetan Plateau –one quarter of China’s total territory- had been split.

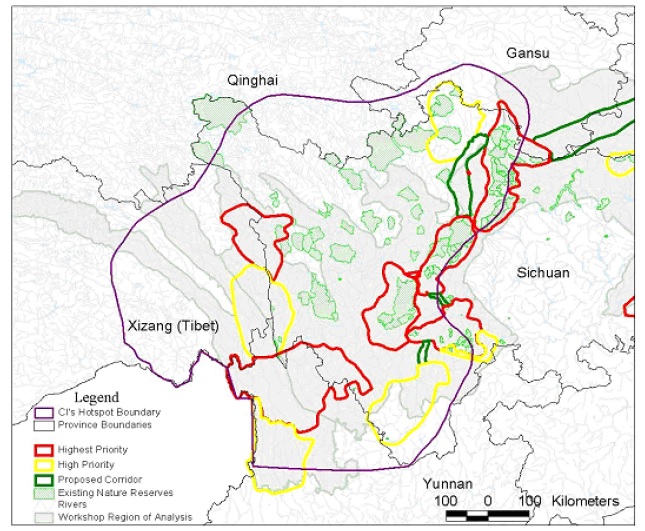

To the wildlife scientists of Conservation International, it was a straightforward calculation of mapping species abundance data, collating all the accumulated transect data of sightings and trappings, to build a bigger picture. It also became clear that during the ice ages, as glaciers spread worldwide, many species had found refuge in the warm, wet, monsoon fed valleys of Kham, and later spread Eurasia-wide as the ice retreated. All of this made Kham biologically important. It was thus self-evident that it needed special protection, so Conservation International presented its case to the Chinese government. CI’s mapping of species abundance even went further north, beyond Kham, into parts of Amdo, both in Gansu and Qinghai provinces. So all five of the provinces into which the Tibetan Plateau has been carved by modern state nation-building –Yunnan, Sichuan, Tibet Autonomous Region, Qinghai and Gansu, are embraced in the singular concept of biodiversity “hotspot.”

THE HOTSPOT VERSUS CCP NATION-BUILDING

CI’s scientists had no idea their high concept was born at just the time China’s leaders were secretly committing to undermine ethnic minority identity and nominal autonomy, for fear of emulating the fall of the USSR. While CI mapped its hotspot, central leaders were secretly considering policy proposals published by influential academics, urging dismantling the autonomy and separate identity of minorities, to be replaced by accelerated assimilation into the language and mindset of the Han supermajority. Hu Lianhe 胡联合 and Hu Angang beat a steady drum of warnings that China, following the Soviet model, had made a serious error by formalising and reinforcing ethnic difference which conceded Tibetans and Uighurs separate status and separate territory.[2]

Central leaders decided not to formally abolish this, which would have been too overt, and caused backlash. Instead, they quietly launched systematic assimilation, shifting school curricula to emphasise standard Chinese and de-emphasize mother tongue, and other policy shifts. Those shifts, from a multi-ethnic country to a single, unitary state of a single Chinese race speaking a single standard Chinese language, culminate in Xinjiang today in compulsory, coercive assimilation en masse.

KHAM CONTENTION

Only years later did it dawn on the conservationists that China might have its reasons for not wanting to reunite Kham and overcome its fragmentation. Kham is where the PLA decisively defeated the Tibetan army in 1950, in Chamdo.

Kham is where the popular uprising against China’s takeover began, in 1956, the start of years of full scale warfare, with air force bombings of monasteries and aerial gunning of fleeing nomads and their slow yak herds.[3] The PLA again triumphed, but the Khampas were warriors, even when faced with death from a distance, by modern artillery and ruin from the air. China has had every reason to keep Kham as fragmented as possible; and any mention of conquest as secret as possible.

Conservation International knew better than to name this giant hotspot either Kham or Tibet, instead blandly labelling it “The Mountains of Southwest China.” Then a decade ago it dropped the entire project, eventually almost scrubbing it from its Critical Ecosystems Partnership Fund (CEPF) website.CI wanted an ongoing presence in China, and discovered the price.

By the time CEPF left Tibet, it had accumulated massive documentation of biodiversity. The bottom line is that, if China is serious about maximising conservation coverage, its designated national parks are largely in the wrong places.

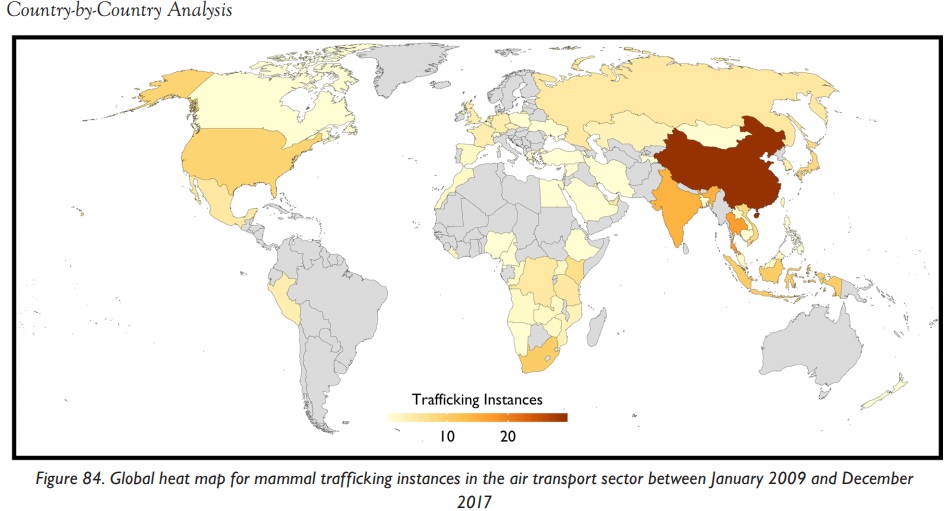

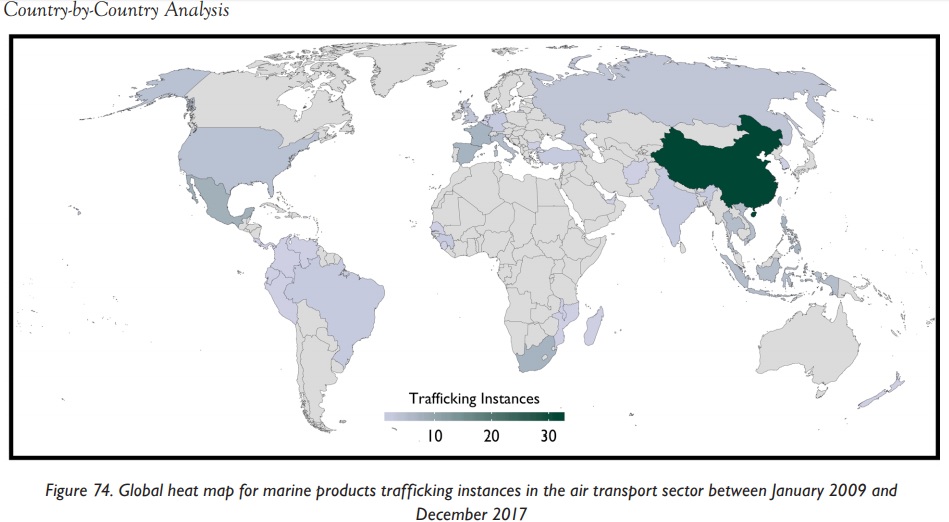

CHINA’S INSATIABLE DESIRE TO CONSUME WILD ANIMAL PARTS

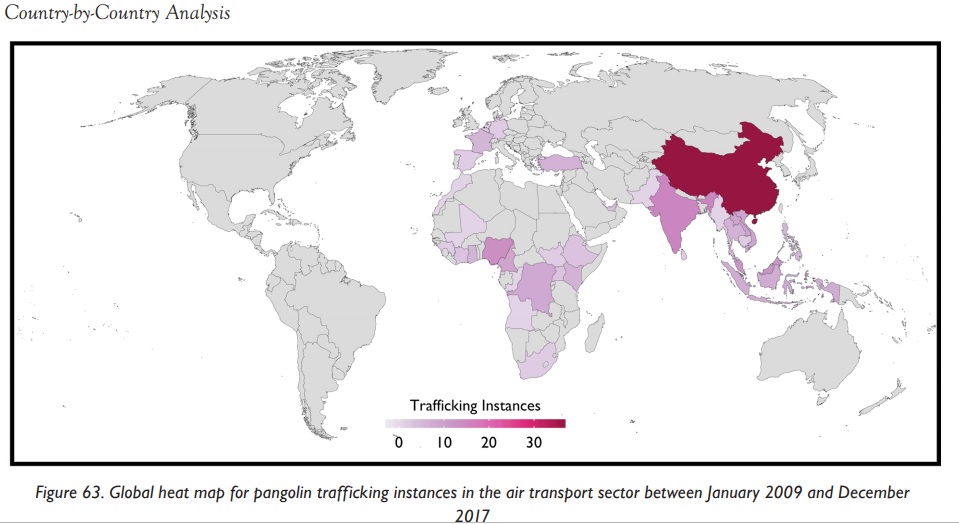

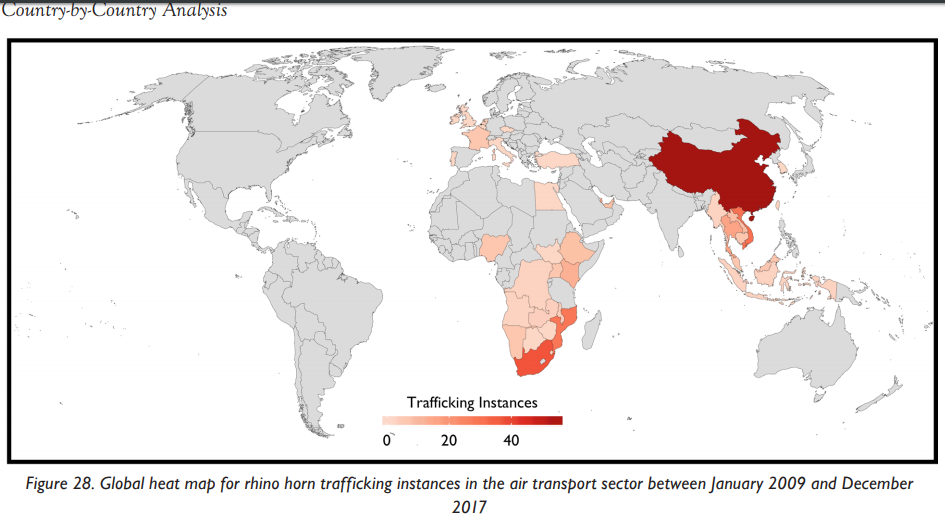

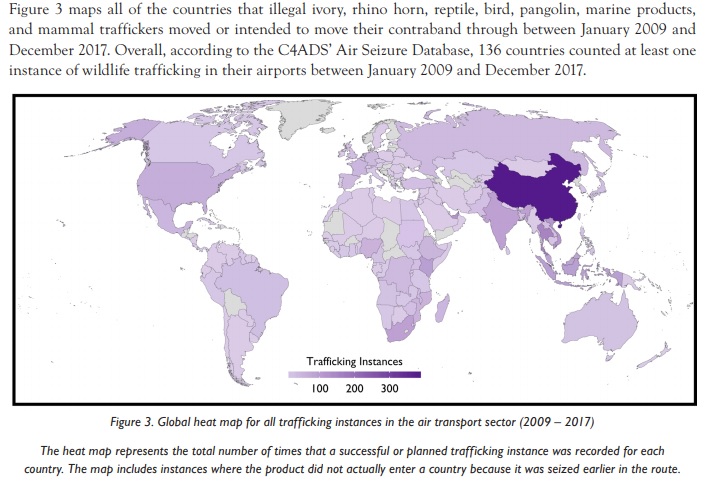

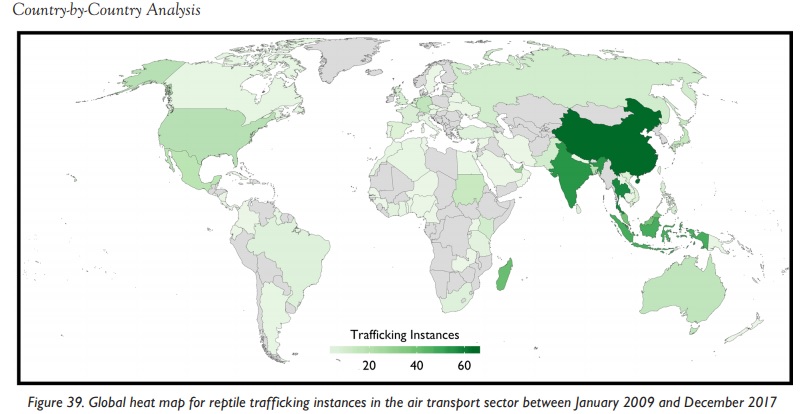

Second contradiction of China’s new story of its embrace of wildlife conservation: in practice, despite global attempts at enforcement, China remains the global destination for almost all wildlife smuggling and trafficking, as has long been the case. China’s appetite for –you name it- seahorses, shark fins, tiger bones, antelopes, bear bile, coral, monkey brains, pangolin scales, rhino horn, ivory- remains insatiable. In fact, as China gets richer, far more people can afford expensive smuggled ingredients once available only to an elite, and the Traditional Chinese Medicine market persists in its belief that all ailments, especially libidinal, are curable by medicines with Chinese characteristics, smuggled from everywhere. An exhaustive 2018 monitoring report by TRAFFIC, In Plane Sight, is exhausting reading, as all the maps point in just one direction.

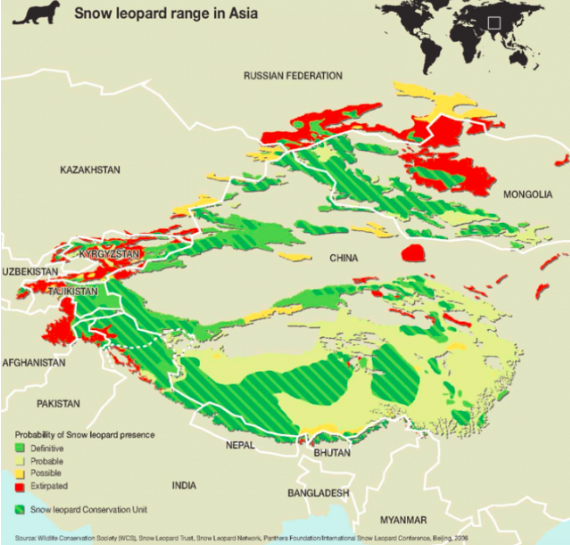

China now proclaims a new found passion to protect Tibetan antelopes and gazelle, snow leopards and brown bears, the state resolutely on guard. To say the least, this is a very new passion, thousands of years after China’s elephant population was destroyed, hundreds of years since all but remnant panda habitat across most of southern China was lost.

China knows it has a reputational deficit to overcome, and CBD Kunming 2020 will showcase the new narrative.

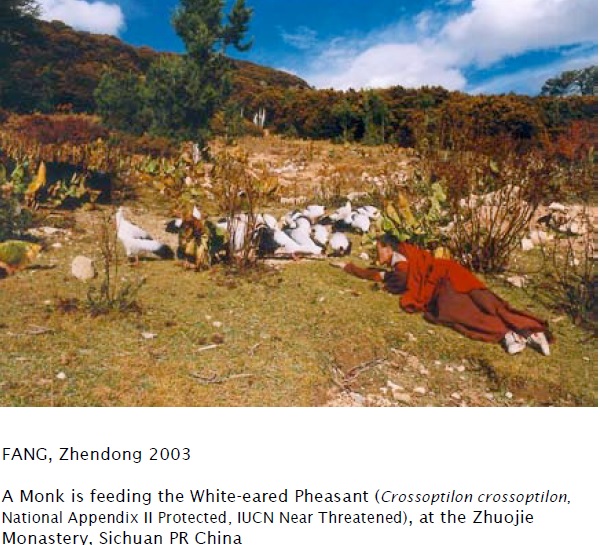

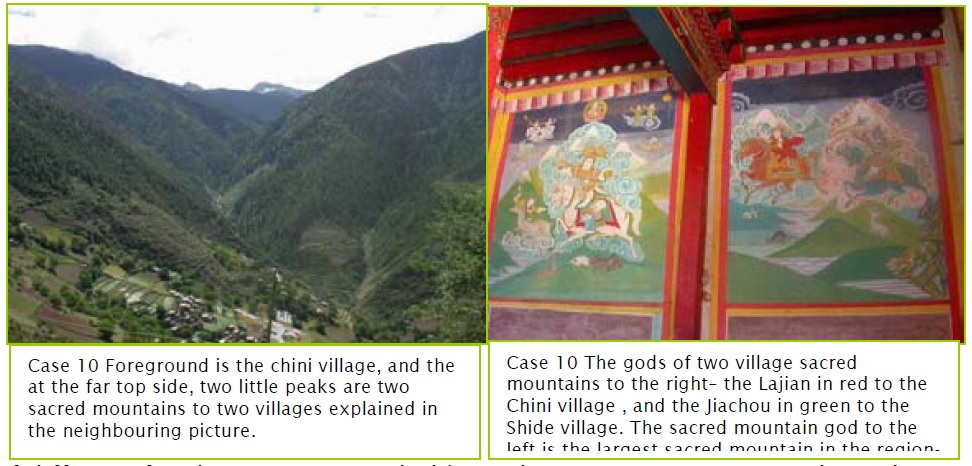

TIBETAN SACRED LANDSCAPES & TRADITIONAL WILDLIFE PROTECTION

Third, positioning the central state as the sole protector and guarantor of wildlife populations erases the long record of local Tibetan communities as stewards of wildlife, including the pastoralists herding their yaks, sheep and goats intermingled with wild antelope and gazelles, all seasonally migrating to remote upland summer pasture each spring, all returning to winter grazing with their newborns.

Now the state is the sole agent, and the embarrassing decades of the 1980s and 1990s, when Tibet was a wild west the state had no interest in, are best forgotten. Upper Tibet was beyond the frontier, a lawless land open to rapacious miners seeking gold in the river beds, and shahtoosh fur on the hoof, slaughtered en masse. State indifference is incompatible with today’s nation-building state assertiveness.

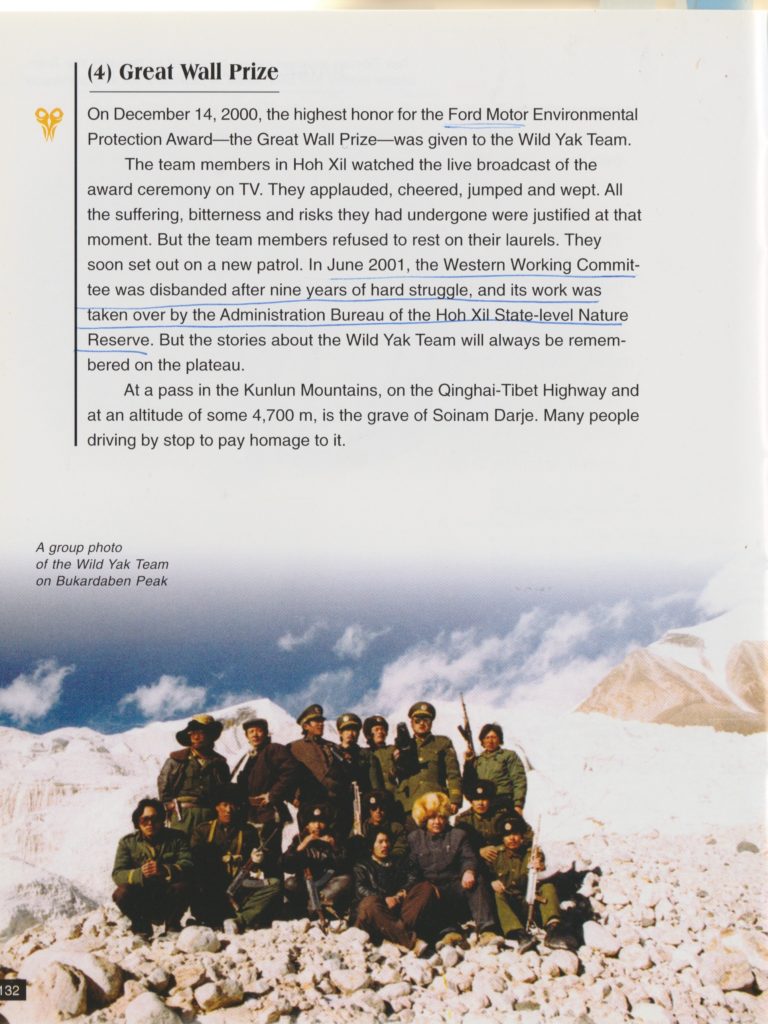

Official amnesia reaches a crescendo with the erasure of the Wild Yak Brigade’s mountain patrol, which scrounged jeeps and fuel to track down and arrest Muslim Chinese hunters who mercilessly shot antelopes for a handful of underbelly fur that fetched high prices in India and Pakistan, crafted into the lightest of shawls, status symbols for offering to the woman who has it all.

Protecting the wildlife of Tibet became, in the 1990s, a global movement, culminating in 1999, in the Tibetan city of Siling/Xining, in a global gathering of “government representatives from China, France, India, Italy, Nepal, the UK and the USA and representatives from the CITES Secretariat, China Wildlife Conservation Association (CWCA), International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW),Tibetan Plateau Project (TPP), TRAFFIC, Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), Wildlife Protection Society of India (WPSI) and World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), as well as experts and scholars specializing in the study and protection of this species.” They mounted a transnational campaign to stop the smuggling of antelope fur to India, to disrupt the criminal networks, which gained momentum by mobilising conservationists worldwide. Their 1999 Xining Declaration is a roadmap of effective worldwide biodiversity action.

China today has somehow elevated one Tibetan, Sonam Dorje, to martyr status, sweeping his grave clean in regular remembrance; while suppressing all recollection of the antelope protection patrols he organised, and the many Tibetans risking all, at a time of official indifference, to track and arrest the ruthless poachers.

In today’s Tibet, local Tibetan community leaders and local government officials who try to protect local environments from expropriation and other threats are arrested, are yet again charged with many crimes and imprisoned for long periods.[4]

The most recent criminalisation of Tibetan environmental protest explicitly charges Tibetans with usurping the state monopoly of power. ”Local authorities stated that a group of village residents along with Zom Ché had founded an illegal organisation in the name of environmental protection.

“Among the 11 sentenced is Wang Ché, a former head of the villagers committee of Do Thrang. The group was charged of ‘setting up illegal organisation with evil intentions, destroying the village social management order through manipulation of village affairs.’ The charges also included ‘creating hurdles for the government policy, not accepting environmental conservation compensation, and stopping others from receiving it, and negatively influencing the regular working of the village and party committees’”.

KUNMING HUB OF COMMUNITY CONSERVATION COMANAGEMENT

FOURTH, Kunming for decades, brought together biodiversity researchers, and global aid donors, together with Chinese scientists and local Tibetan communities, all working together to document species abundance, traditional conservation successes, problems and prospects. This was a fruitful program, one of many examples being the 2005 A Rapid Biological Assessment of three sites in the Mountains of Southwest China Hotspot, Ganzi Prefecture, Sichuan Province, China, a 174 page report on the abundance of wildlife in Kham Kandze prefecture of Sichuan. Not only did it bring together dozens of field researchers from across China and across the world, it also brought together funding and institutional support from Conservation International, The Disney Worldwide Conservation Fund, Sichuan Academy of Forestry and Sichuan Provincial Forestry Department. Other funders of this collaborative effort to map the Kham biodiversity hotspot included World Wide Fund for Nature, The Nature Conservancy, Ford Foundation, the World Bank, European Union and several government aid donors.

These reports now gather dust; as China has shifted its focus north, to the river sources, which provide China with its water tower, biodiversity becoming the rationale for depopulating the watershed. The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund program in Tibet is no more. Its legacy is rich documentation, in obscure online corners, of a wealth of community based conservation research results.[5]

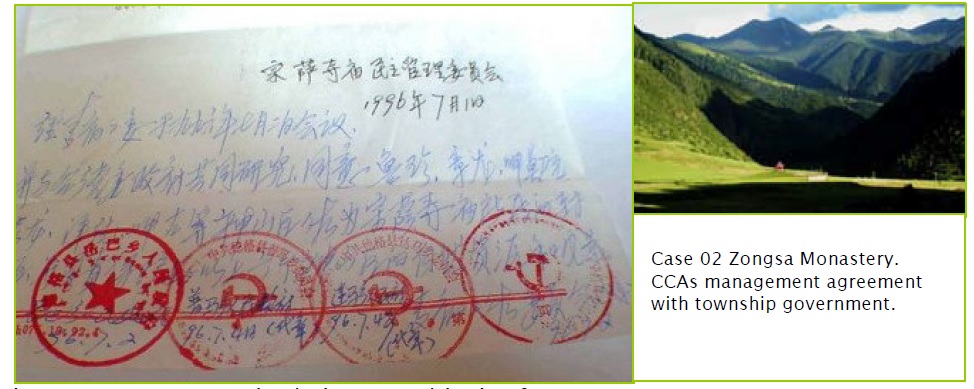

Another example, also from 2005, is Xu, J., E. T. Ma, D. Tashi, Y. Fu, Z. Lu, and D. Melick. 2005; Integrating sacred knowledge for conservation: cultures and landscapes in southwest China; teamwork by Tibetan, Chinese and international conservationists on local community knowledge as the key to conservation success in the Kham “hotspot.”[6] That teamwork is the reason for today’s official amnesia, because those embarrassing reports of 10 to 20 years ago point to local knowledge and local agency, in partnership with scientists and official institutions, as the best strategy for achieving actual biodiversity protection. Today’s China insists the central state alone is the guardian and guarantor of biodiversity, employing exnomads to police the clearance of Tibetan pastoralists from their pastures.

As this decade plus of global endeavour to map and conserve wildlife and entire habitats of Kham came to a halt in 2008, when China accused Tibetans of “killing, looting, burning, smashing” everything Han Chinese, Chinese biodiversity scientists made one last attempt at gathering together everything they had learned from Tibetan communities. They had learned a lot. China has now pivoted decisively away from community conservation in Tibet, for fear it will only strengthen Tibetan identity, embracing the sovereign state as sole actor.

KUNMING INDIGENOUS KNOWLEDGE CHRONICLER SHUT DOWN

Fifth, Kunming was the centre of this co-operative, bottom-up work to bring together Tibetan local communities, other Yunnan minority ethnic communities, scientists, global finance, and the state, in the Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund. Kunming’s own institutional base for this embrace of indigenous knowledge was the Yunnan Institute of Botany’s Centre for Biodiversity and Indigenous Knowledge (CBIK).

Try searching for www.cbik.org and see how far you get. For many years CBIK provided support, publication platforms and staged conferences bringing together a global collection of conservationists, all dedicated to weaving traditional conservation practices together with modern science. CBIK was closed a decade ago, its online legacy almost erased, while its parent, the Kunming Institute of Botany is now fully in line with official top-down policy, inscribing scientific categories onto Tibetan landscapes as far away as Kailash Sacred Landscape in far western upper Tibet. No Tibetans need apply.

China needs us all to forget that Kunming, a long way from Beijing, once cheerfully embraced community conservation, indigenous knowledge and bottom-up effective conservation grounded in sacred mountains, landscapes and pilgrimage. China wants us to look only ahead, to the Conference of Parties of the Convention on Biodiversity in Kunming, October 2020.

China wants to be congratulated as the most capable constructor of ecological civilisation the world has ever seen. It’s not that simple. Conservation with Chinese characteristics uses the rhetorics of biodiversity to inscribe exclusive and exclusionary state power onto vast Tibetan landscapes, while erasing memories of how it all could have been done by Tibetan communities instead of excluding them.

We regret this stifling. Where would conservation research and community based active protection could be by now if they had continued? Today there would be many Tibetan conservation NGOs, confidently working with Chinese partners, to protect wildlife, whole landscapes and Tibetan communities together. Grassroots community-based organisations would have kept growing, all over Tibet, with support from elite institutions such as Peking University, not only conserving endangered species but financing their work by running select ecotours to remote areas, with local Tibetan communities hosting visitors in their homes and earning income as well.

This is not a fantasy. It is a trajectory established during the Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao years, which, in a low key way managed to quietly persist, even after China’s decisive turn, under Xi Jinping, to centralisation, authoritarianism and assimilation of minorities. It tells us much about Tibetan adaptability and resourcefulness that conservation NGOs such as Shan Shui manage to keep going.

In the wider world, community conservation, rather than top down statist rigid territorial zonings, grows and grows, embraced by just about everyone, including the Convention on Biodiversity (CDB), which, in its Article 8j, specifically encourages community conservation on the solid basis that historically it has been far more successful than state driven efforts, since it is grounded in sacred landscapes local communities hold dear.

Kunming 2020 CDB will be a test: which way will CDB go?

EXTINCTION REBELLION OR MULTILATERAL CONVENTIONS?

What is at stake is the future of life on earth. The issues are enormous. Here is a list, provided by the International Institute for Sustainable Development, in diplomatic language:

- What should the new set of biodiversity targets look like? How can they maintain ambition while being specific and promote action on the ground? How should they align with other global targets, including the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)?

- How can the international community finally tackle the root causes of biodiversity loss? Are biodiversity mainstreaming and cooperation among multilateral environmental conventions the only possible options?

- What is the role of voluntary commitments for biodiversity? Should they be included in the post-2020 framework?

- What should be the place of means of implementation? How can biodiversity commitments and targets be coupled by specific commitments on finance, capacity building and technology transfer?

- What mechanisms, tools, and review mechanisms can support implementation at the national and local level?

- How can the post-2020 framework integrate different worldviews, in particular those of indigenous peoples and local communities?

- How can the broader public be engaged in biodiversity governance? What is needed to catalyse societal action for biodiversity?

This adds up to a huge agenda in Kunming, with widespread unease that leaving it all to governments, and the inter-national system, only produces fudges and diplomatic phrasings masking hollow promises that cannot be held accountable. Danger signs include the prospect that, to get things moving, the Convention on Biodiversity (CBD) might have to agree to let each country set its own targets, merely voluntary commitments, with no mechanism for holding them accountable. That is just what happened in 2015 in Paris, at the climate talks, with results that fell far short of what is needed.

Will these negotiations be better for being staged in a city

and a country intending to keep out the rebellious extinction protesters?

[1] E. Dinerstein, and others, A Global Deal For Nature: Guiding principles, milestones, and targets; Science Advances, 2019; 5 : eaaw2869 19 April 2019

[2] Hu Lianhe, 前苏联改革失败和国家解体的再反思, Rethinking the Failure of the Reform of the Former Soviet Union and the Disintegration of the Country, 湖北行政学院学报, Journal of Hubei Administration Institute,2005 年第3 期 总第21 期 No.3 , 2005, vol 21

[3] Li Jianglin [李江琳], When the Iron Bird Flies in the Sky [当铁鸟在天空飞翔], Taipei: Lianjing Press [联经出版社], 2012),

Carole McGranahan, Arrested Histories: Tibet, the CIA, and Memories of a Forgotten War,

Charlene Makley, The Violence of Liberation: Gender and Tibetan Buddhist Revival in Post-Mao China, 2007

[4] Liu Jianqiang, Tibetan Environmentalists in China: The King of Dzi, Lexington Books, 2015

- [5] Shen, X., Z. Lu, S. Li, and N. Chen. 2012. Tibetan sacred sites: understanding the traditional management system and its role in modern conservation. Ecology and Society 17(2): 13.

- http://dx.doi.org/10.5751/ES-04785-170213

- https://www.cepf.net/sites/default/files/final_cbik_consequencesswchina.pdf

- Workshop on Experience Sharing for Community Based Monitoring and Inception Workshop on Community Based Monitoring Network, 2007

- Assessing Five Years of CEPF Investment in the Mountains of Southwest China Biodiversity Hotspot, CEPF 2008, https://www.cepf.net/sites/default/files/final_mswchina_assessment_aug08.pdf lists the dozens of communities, partners and outcomes.

[6] Ecology and Society 10(2): 7. http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol10/iss2/art7/