TECHNOLOGIES OF MAKING TIBET CHINA’S

Blog 1 of 4 overviewing China’s long term strategies

Almost all of China’s interventions in Tibet share a common purpose, very seldom named. How can we sum up what China does, in the name of development, What is the common thread, over decades, shaping what China does, in the name of development, modernity, civilisation?

Here’s a clue. China has frontiers with 14 countries, so lots of frontier regions. Several are officially named after nonHan ethnicities. Does China feel compelled to prefix the name with a possessive noun? Is everyone supposed to say China’s Inner Mongolia? China’s Xinjiang? China’s Guangxi? China’s Guizhou? No need. Yet China does as a rule routinely say China’s Tibet. Why?

Tibetans in exile find that possessive prefix deeply offensive; but it also suggests an anxiety that China’s ownership is not a given, not an established fact, not an evident ground truth.

Making the plateau massif China’s is an ongoing experiment in nation-state building that still has a long way to go before China could drop its anxious insistence on possession of a thousand plateaus the size of Western Europe, that added one third to the bulk of China’s mapped extent.

This blog is a dive into the many technological experiments China has tried, over many decades, to make China’s Tibet actually Chinese, with limited success. There is a common thread connecting all of the technologies of development China has inscribed in Tibet. Technologies we think of as focussed on separate issues: livestock management in Tibet, national parks, hydro dams, infrastructure construction and mine sites. They all claim to benefit Tibet and Tibetans. All have an underlying purpose, in a word, governmentality.

THOSE INSCRUTABLE TIBETANS

Until the 1950s, no outside power had made any attempt to govern Tibet, still less remake Tibet in the image of the invader. Nepal invaded in the late 18th century, Britain in the early 20th; neither sought to govern. The Manchu Qing asserted power in the early 18th century., making no attempt to govern. Whatever one makes of the endless arguments of legal historians as to status and sovereignty in international law, the reality on the ground was no attempt to govern the lands and peoples of Tibet. So revolutionary China had to start from scratch, to make Tibet China’s.

Only in Xikang province, a slice of eastern Tibet, in the early 20th century did China exercise actual control over what are now the “autonomous” prefectures of Kandze and Ngawa, in Sichuan. In reality, China did little to govern, beyond imposing predatory extraction of tax from Tibetans.[1]

WHERE IS THE MASTER PLAN?

China has never had a master plan for mastering Tibet, for making scrutable the inscrutable. Mao hesitated for years to impose class warfare and communisation, knowing there were almost no Tibetan communists to welcome the invading troops as liberators. In 1959 he reversed completely, commanding Han cadres to drive all livestock, all Tibetans and even their pots and pans into communes, with cadres holding life and death power over the masses. Thus began the great experimentation aiming to make Tibet China’s.

The experiment failed. Famine ensued. The tenth Panchen Lama rapidly learned CCP jargon and appealed directly to Mao, in Marxist-Leninist language, to halt the starvation and the propaganda lies. China’s Tibet was further away than ever.

Mao was not done with the barrel of the gun as the means to achieve actual control over lands and people of Tibet, with Red Guard factions battling in the streets to be recognised as the most zealous enforcers of class warfare, and liquidation of class enemies.

Yet revolutionary China had adopted Europe’s territorialised sovereign nation-state 民族—国家as its model, so there was an urgent need to somehow transition the entire Tibetan Plateau from alien rule imposed by PLA garrisons, towards integration into a modern nation-state in which Tibetans identify as citizens of China, loyal to the party-state and to distant Beijing. That was core agenda 60 years ago; it remains core agenda now.

FROM DESTRUCTION TO CREATION

After the Cultural Revolution failed to smash everything Tibetans held dear, an exhausted China turned to wealth creation as its aspirational goal. The invitation to get rich resonated across China, not so much in Tibet. So the era of experimentation grew and grew over the past 45 years, seeking a strategy to make China’s Tibet a reality, not just a dubious assertion.

China’s many experiments in developing Tibet are all experiments in governmentality, in making the state a tangible presence, in command, in lands that never had need of the nation-state, including many lands in eastern Tibet that had been proudly stateless, repudiating Lhasa as well as Beijing.[2]

In the past 45 years a long menu of governmentalities have been experimentally imposed on Tibet, all in the name of development, modernity, progress, prosperity, civilisation, all obeying the laws of history. This Rukor post series examines those technologies of governmentality, firstly for their efforts to make Tibet -both land and people- scrutable, legible, quantifiable and controllable. A more detailed dive into China’s technologies of governmentality is published by Turquoise Roof, turning to the Ma Chu/Yellow River of Tibet to illustrate all of these technologies in action, on one Tibetan river.

Secondly, governmentality is much more than the nation-state imposing its reach and grasp top-down. The civilising mission of governmentality requires the objects of the state’s panoptic scrutiny to accept and internalise their loyalty to this ideology of modernisation with Chinese characteristics. https://rukor.org/civilising-those-green-brained-tibetans/

That is why Foucault invented a deliberately ugly word to include the active social engineering of the state to be not only present in everyone’s lives, but accepted. Hence the current, accelerating CCP mass campaign to assimilate all Tibetans into internalising “Chinese characteristics.”

2024 poster promoting textbooks teaching the single Zhonghua race:, one flag, one people, one language, all salute. Source: https://www.hbqj.gov.cn/zjq/xwzx/gzdt/202409/t20240923_5344607.html

Thomas Heberer: “At the 17th National Congress of the CPC in 2007, ‘civilised’ (wenming) was mentioned 13 times in the report by the then-General Secretary Hu Jintao. At the 19th Party Congress (2017), Xi Jinping referred 45 times to the term, which shows that it had become increasingly prominent. He stressed that between 2035 and 2050 the country should be built into a ‘civilised’ modern nation, and the ‘fundamental task of cultivating the people in terms of moral integrity’ and ‘moral, intellectual, physical and aesthetic terms’ must in any case be realised. The ‘civilisational level of the whole society’, the establishment of a civic morality based on traditional Chinese virtues, public morality and strict private morality is according to Xi one of the core tasks of the development until 2050.

“There is, however, another term in use for discipline, guixun (规训). But interestingly, the Chinese term guixun stands not only for disciplining but also for self-disciplining. Effective disciplining requires, in turn, supervision and surveillance technologies. People should adopt and memorise codes of conduct, thus making them their own. The ultimate objective of disciplining was, and is, to establish individuals’ self-control.”[3]

Tibet cannot really become China’s Tibet [or China’s Xizang] unless and until the Tibetans assimilate Chinese characteristics, language and values, becoming part of the Zhonghua Chinese race. This is far from accomplished, especially in central Tibet, where China’s technologies of development have such poor outcomes. Tibet Autonomous Region remains an embarrassing laggard in all cross-provincial statistical comparisons; the standard solution being to simply omit TAR from provincial listings of GDP, output and incomes, as if no data exists. The statistics do exist: the annual TAR Statistical Yearbook is over 1000 pages, but it consistently shows only how U-Tsang lags, by any measure of development. Embarrassing.

A 2024 TEXTBOOK TEACHING ASSIMILATION

Ivan Franceschini: “A new Chinese Government textbook for university students, An Introduction to the Community of the Zhonghua Race 中华民族 共同体概论, promotes President Xi Jinping’s vision for governing the country’s diverse population. This approach shifts away from celebrating cultural differences—what the political scientist Susan McCarthy once termed ‘communist multiculturalism’—and towards a Han-dominant identity, which is a form of racial nationalism inspired by sociologist Fei Xiaotong’s concept of ‘multiple origins, single body’ 多元一体. While the Constitution of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) as amended in 2018 guarantees minority rights and political autonomy through the framework of ‘minority nationalities’ 少数民 族 , the textbook suggests that Tibetans, Uyghurs, Mongols, and other Indigenous groups should eventually assimilate into Han culture, raising concerns about the future of minority languages and traditions.”[4]

One of 14 posters teaching key slogans of the Strengthening the Chinese Nation’s Community Consciousness Theme Promotion Month, 2024. Each September is to be Chinese Nation’s Community Consciousness Theme Promotion Month https://www.hbqj.gov.cn/zjq/xwzx/gzdt/202409/t20240923_5344607.html

TOO FAR, TOO HIGH, TOO COLD

There is a popular belief that China does long term planning better than anyone, a belief fostered by a ruling party that issues goals, targets and objectives for 2035 and 2049; a party proud of inheriting the legacy of the Confucian sages, and of scientific rationality.

But in reality Tibet has confounded strategies that worked everywhere else, as the Han, over many centuries, expanded south and later west, always able to people newly conquered lands with desperately poor, landless Han Chinese peasants, sent in after the conquering troops, to people the land with folks loyal to the emperor, to plough the soil, grow the crops needed by the troop garrisons dug in for the long haul of alien rule.[5] It had always been possible to people newly conquered lands by sending in desperately poor, landless peasants to till the soil of the new frontiers, and market their produce to the garrisons of troops dug in to enforce conquest. As recently as the 1950s, this strategy was successfully implemented in Xinjiang, with millions of nonUighur settlers demobilised onto Uighur lands.

Only in Tibet was this early modern governmentality strategy unavailable, because Chinese peasant farming is not transferable to the cryosphere. Hence a new list of governmentality experimentation was urgently needed, and is still in progress, now actually accelerating, as China’s grasp expands, attempting to match it’s ambitious reach.

The Tibetan Plateau was and is too high, too cold, too hypoxic and above all simply too big to be made Chinese by waves of settlers. This never troubled the Qing dynasty, for whom “the outer peripheries, or “unfamiliar aliens” sheng fan, were geographically, culturally, and ethnically far distant. “Nomadic or seminomadic, communities here were not formally entered into the official household registry nor required to pay imperial taxes. Tribal chieftains were obligated to acknowledge the Celestial Emperor but were required to make less frequent pilgrimage trips. Internal affairs were left to themselves.” [6]

Not any longer. Modernity, nation-building and revolution all required governmentality. Neighbouring Xinjiang, north of Tibet, in the 1950s was made Chinese by this standard method, making the Uighurs peripheral in their own land. NY Times correspondent Ed Wong has just published a book about his father, one of the Han pioneers of making Xinjiang China’s.

But no standard nation-building strategy was suited to the cryosphere, the frigid lands which added one third to the territorial size of China’s geobody. To make Tibet China’s there was no recipe, no formula naturalising alien rule, it would have to be a crossing of the river by feeling for each stone. But the river had to be crossed. The Tibetans had revolted, including the liberated serfs who preferred their lamas and aristocrats more than the Han cadres who insisted on total power, and obedience.

In the 45 years since China committed to pushing and pulling Tibet into China, deploying a long menu of technologies of development, selective portions of Tibet have become enclaves of intensive extractivism; engineering corridors for infrastructure that shrinks space and accelerates time. Yet most of Tibet, and most of the seven million Tibetans (2020 Census data) remain outside the development zones, yet much affected by the glamourised mentalities of governmentality, instantly accessible on their ever present smart phone, throughout Tibet.

This blog focuses on the technologies China has deployed, to govern Tibet from afar, thus overcoming the impossibility of flooding Tibet with poor Han. These are all technologies of development, although China’s twin objectives of development and securitisation have now merged so wholly that technologies of DNA profiling of individual Tibetans, grid management, surveillance, big data real time analysis and predictive policing are major aspects of China’s total governmentality package.

MUTUAL BENEFIT: COMPARATIVE ADVANTAGE: AN ACTUAL WIN-WIN

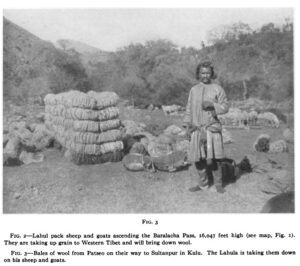

First, some context. If China sincerely wanted to develop Tibet and generate new opportunities for Tibetans, what could it have done? For development economists, the alternative -never attempted- is straightforward: China and Tibet are adjacent, contiguous, two markets, two economies that could be mutually supportive if they trade what they do best, that is in demand. That was the logic of the tea and horse road winding through the mountains, bringing sturdy Tibetan horses to China, the Tibetan trade caravans returning upcountry laden with bricks of tea.

Economists have a concept defining this great experiment in development that China never tried: comparative advantage. China’s failure to assess what the Tibetan production economy abounds in -butter, dairy and wool- and match it with Chinese demand, is the great failure that overshadows all claims to win-win prosperity in Tibet, driven by China’s benevolence.

While comparative advantage has been critiqued as a neoliberal approach, requiring financialisation and a commodity export economy, rural Tibet did have surpluses of butter and other dairy products, wool and the famous trading of hardy Tibetan ponies for Sichuan tea.[7]

Source: Source: H. Lee Shuttleworth, A Wool Mart of the Indo-Tibetan Borderland, Geographical Review, Vol. 13, No. 4 (Oct., 1923), pp. 552-558

China today talks of comparative advantage, part of its rhetoric of development in Tibet, but has never invested in what it calls “animal husbandry with Tibetan characteristics”. There has been no win-win. China simply closed Tibet’s borders, shutting off the export of Tibetan wool via Calcutta to UK and US, and simply requisitioned the wool for the mills of Shanghai, without payment.

What does comparative advantage look like, on the ground? While China was stripping Tibet in 1960, the Soviet Union was finalising the collectivisation of pastoralism in Mongolia.

“Leaders in the Mongolian People’s Republic used the collectivization campaign from 1956-1960 to change the way in which Mongolians interacted with animals and the environment. Collectivization, which followed the Soviet model, was the confiscation of private livestock to create collectively owned and worked livestock herds, and was seen as one of the building blocks of a modern socialist state. Today there is increasing interest in pursuing co-operatives and collectives inspired by the socialist negdel model. These co-operatives address many of the same problems found in the socialist period, as well as issues of increased desertification from climate change and mining. These new co-operatives lack one of the main features that made socialist collectives function: a state monopoly and centralized plan of inputs and outputs. Without the state as a guaranteed customer and inputs incoming regardless of if quotas were made, contemporary collectives are in a far more precarious position. But numerous Mongolian herders agree it is better than the alternative. Co-operatives rely on pooled resources to alleviate risk, but a large enough disaster would presumably not receive the centralized state response that the socialist government was capable of offering. But given the increasing precarity due to climate change and mining a safety net of any kind is attractive.”[8]

China now claims comparative advantage is one of the drivers of its developmentalist strategies, yet classic comparative advantage is grounded in identifying the strengths of an economy on the periphery, compared to demand in the metropole. Since Tibet was widely known in global markets in the early 20th century for its exported surpluses of wool, identifying Tibet’s comparative advantage was easy.[9]

In revolutionary China, the woollen mills of Shanghai wanted wool, especially at a time when China imported very little of anything, and Chinese soldiers, fighting in icy Korea, needed woollen overcoats. But the semi-fine wools of Tibetan sheep, goats and yaks were requisitioned, not paid for, not the beginnings of fostering the endogenous development promoted by comparative advantage.

China failed to invest in adding value to Tibet’s comparative advantages. Immediately after a three year war to conquer Tibet, 1956 to 1959, the last thing China was willing to do was to strengthen the Tibetan economy. Yet the rapid imposition of land consolidation into communes was done in the name of increasing production, which all belonged to the state. The great famine of 1959-1961 ensued.

China has never been interested in strengthening the existing strengths of the Tibetan economy, nor has there been any investigation into what comparative advantages of Tibet can be identified and evaluated for their potential to supply China’s demand. The sole exception is water, a free public good, now commodified, and more recently the electricity generated by those waters, now surrounded by solar and wind installations as well as power grids. None of these are grounded in what Tibetans make, or could sell into what has become a market economy. Token efforts at intensification of livestock production are predicated on consolidating lands, making most nomadic livestock producers redundant, with the profits of agribusiness intensification concentrated in feedlots, abattoirs and “demonstration parks” all run by Han.

Sixteen technologies of development China deploys in Tibet:

- Carrying capacity, stocking rates, assessed by satellite sensor cameras https://youtu.be/Kyzql8FriIY?si=_huwv-D4Ysugf6UL

- rangeland degradation, pest control, chemical warfare on grassland rodents

- engineering corridors, railways, highways, high speed rail, tollways

- extraction and mine site concentration of critical minerals,

- biomass growth, watershed protection, carbon sequestration, satellite camera managed

- natural capital valuation

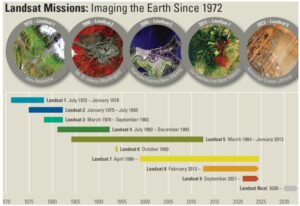

- biodiversity conservation, core zone redlining, national parks, remotely managed Normalized Difference Vegetation Indexing by satellite cameras

- geoengineering the clouds of Tibet to force rainfall into Yellow River

- water provisioning of lowland China from “China’s Number One Water Tower”

- wetland protection by remote management

- intensive agribusiness aquaculture production of alien fish in Tibetan dams

- foamed concrete panel manufacture, Lego construction of border villages

- demonstration bases to teach productivity and commodity chain efficiency,

- dam design and construction for flood control, drought mitigation, extracting energy from rivers, solar power from sunlight, electricity from wind, pumped hydro to turn dams into batteries, hydropower to separate water into oxygen and hydrogen to be stored and pumped by pipeline to distant markets,

- ultra-high voltage DC long distance transmission of electricity,

- big data real time pattern detection of Tibetans as security threats.

The list of technologies China has inserted into Tibet is long, increasingly implemented through remote satellite cameras and big data predicting what happens next, based on detecting patterns in what tech has monitored in the past.

A long list generates a torrent of data, not only official policy decrees but thousands of scientific research reports generating data points measuring a huge, complex landscape almost completely unknown, unfamiliar and alien to China until the 1950s. Even the clouds of Tibet were new to China, prompting a new atlas of clouds of Tibet in the 1980s.

Do these 16 technologies add up to an ensemble, sharing a common purpose? Amid this torrent of data trying to measure everything measurable, can we discover a pattern, that consistently drives this accelerating marshalling of data? Do the policy decrees issued from Beijing add up to a consistent goal?

Foucault’s “Discipline and Punish” in Chinese

IN A WORD: GOVERNMENTALITY

Governmentality is at the core. Making the lands and peoples of the Tibetan Plateau knowable, measurable, scrutable, legible, governable, controllable, defines each of the technologies in the list.

When Foucault coined this deliberately ugly word, he explained it as “the ensemble formed by institutions, procedures, analyses and reflections, calculations, and tactics that allow the exercise of this very specific, albeit very complex, power that has the population as its target, political economy as its major form of knowledge, and apparatuses of security as its essential technological instrument.”[11]

What does this mean? “Governmentality is not simply a matter of what is usually called government. Governmentality is not just whatever it is that governments do. It is an ensemble, a coming together or emergence of a set of practices that come to occur largely through the institutions of the state . These practices have as their object populations, which are to be mobilized and understood. This understanding, and the uses to which it can be put in mobilizing populations, is had through political economy. Finally, this object and this knowledge are realized largely through the apparatus of security.”[12]

In the 1950s revolutionary China inherited from the Manchu Qing dynasty military campaigns of the 1720s a concept of China that included all of Tibet, a concept enforced by the 1950s military conquest by the People’s Liberation Army.

Although that war took three years and up to a million lives, conquest was the easier part. What to do with lands that added one third to the size of the sovereign nation-state that called itself the People’s Republic of China?

The military dug into garrisons in every Tibetan town, to ensure conquest could never be challenged. But what next? An empire is not a unitary nation-state. Nation building 民族工作is an arduous, complex process requiring many assertions of state power over land and people, if security is to be established. The 16 technologies listed are China’s menu of governmentality experiments in nation building, making Tibet China’s.[13]

Some of these experiments failed, some succeeded in fulfilling their objectives. Some on the list contradict others; for example, in the 1980s Tibetan nomads were required to erect fences -largely at their own expense- to keep their herds within boundaries drawn by state surveyors. Then in this century, the nomads were ordered to demolish those fences to allow free seasonal migration of wildlife, part of the governmentality shift into “construction of ecological civilisation.”

What do these technologies have in common? What makes them an ensemble? First, all are technologies of development. The modern nation-state of China had to experimentally impose a long list of technologies that are presented as the advance of modernity, development, productivity, leading to eventual prosperity. Officially a moderate level of prosperity, xiaokang, was achieved throughout Tibet by 2020.

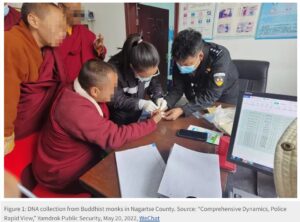

More technologies could now be added to this list, that make no claim to building development, which are solely to make each and every Tibetan visible and legible to the security state. This includes the compulsory insertion of security spyware on smartphones of Tibetans, compulsory DNA collection of Tibetan individuals, grid management of towns, surveillance cameras on every street, and big data centres for real time predictive policing enforcement based on algorithmic detection of individual behaviours.

Since, as Foucault reminds us, security is the objective of all governmentality, we could extend the list to include technologies that implement securitisation. However this list of 16 is all in the name of development, and can be assessed for their impact on human welfare and development. It is possible to carefully analyse the developmentalist rationales of each policy, and their actual impacts on the lifeworlds of Tibetans who are the objects of state builder scrutiny. Since there is by now a huge quantum of data, especially in Chinese, on the actual outcomes of policy keyword slogans, it possible to evaluate the gaps between propaganda and performance.

The conclusion is that while the rhetoric of development is primarily about people, this list of technologies is primarily about land; about making landscapes scrutable, governable, onto which the presence of the state is inscribed; largely by removing the traditional owners to distant frontier districts. In the absence of customary landscape curators, huge areas can be zoned for a spectrum of governmentality purposes. Some landscapes are zoned for water provisioning to distant consumers in lowland China. Some are packaged as primordial wilderness attractive to mass domestic tourism. Other landscapes are classified as economic, for the intensive extraction of minerals and hydroelectricity exported to distant factories; and for intensive industrialisation in economic zones in Tibet.

Securing all of these lands as Chinese, across a Plateau the size of Western Europe, remains an arduous task of governmentality, yet to be completed. Securing the active on ground presence of the state necessitates making Tibetans insecure, usually by displacing and disempowering them, relocating them to resettlement villages, dependent on state transfer payment rations, required to patrol high altitude frontiers of international border districts, since Han from the lowlands lack stamina.

GOVERNMENTALITY BY REMOTE CONTROL

One strength of these technologies is that they extend the gaze of the central party-state into all landscapes, remotely, with little need of populating frontier districts with emigrants from the lowlands. Rural sociologist Lu Dewen states: “Government departments and bureaus are increasingly relying on modern technology to exert greater supervision and control of the grassroots. The departments of land management, forestry, ecological and environmental protection, and others have all begun to make use of satellite-based monitoring technology. When these departments use satellite images to identify patterns and decide what reforms and modifications must be made on the ground, the images tell the true story: there is no room for sophistry or quibbling by local officials, who can only do as they are commanded.

“But the higher authorities fail to recognize that the so-called “truth” revealed by these satellite images requires interpretation and analysis. Explanations [of the same phenomena] may vary widely between different geographical locations and levels of government. This refusal to brook interpretation and analysis has become the most prominent feature of technological governance.”[14]

It has taken many decades for this ensemble of governmentality projects that inscribes China’s state into Tibetan lands to get this far, with many decades ahead of further experimentation. But the pace is now intensifying, accelerating.

CHINA DISCOVERS THE CRYOSPHERE

From the outset, in the 1950s, China’s ambitions were thwarted by Tibet’s cold climate.

China has had to begin anew, with no ready technologies or strategies of governmentality available, other than the Soviet Union, much of which China copied, and later regretted, such as the assigning of territorialised autonomy for minority peoples, notably the Tibetans and the Uighurs.

At the highest level, after much internal debate among the establishment elite early this century, the decision was taken to retain titular regional autonomy, because overt cancellation would damage China’s international reputation. Instead, technologies of governmentality were deployed to effectively absorb and assimilate all seven million Tibetans into the dominant Zhonghua Han Chinese race.

Our list of 16 technologies of developmentalist governmentality has remarkable internal consistency, in that every one of the 16 has disempowered, displaced and dispossessed rural Tibetans. All reduce Tibetan autonomy, agency and capacity to generate livelihoods on customary landscapes.

All remove Tibetans, in the name of modernity, progress, prosperity, development and biodiversity protection. They now relocate Tibetans in mass produced border villages where they are deployed to patrol frontier districts, since so few lowland Han Chinese can handle the strenuous exercise of patrolling the borders at high altitude.

All of the 16 technologies make Tibetans more legible, scrutable by centralised power. All build security in a region China designates as a security buffer, enabling it to instead focus its force projection power out to sea, towards Taiwan.

The racist ideology of assimilating all ethnicities to a Han norm is now overt, unapologetic, an unashamed civilising mission. Not only is there a new textbook, which must be studied by university students all over China, the assimilationist message is promoted by mass media documentaries in which minorities embrace their assimilation, which is the purpose of governmentality.

https://tv.cctv.com/2024/09/26/VIDEI5HU5w03RmU9wtxqrOm3240926.shtml

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w4_BBzVduSY

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7RXBCueCTnE&feature=youtu.be&utm

For years this assimilation policy was a state secret, declared only within the CCP, 内部参考not publicly, so progress was slow, lacking public slogans, mass mobilisation and overt campaigns.

Meanwhile, our internally consistent list of 16 technologies of development gradually but steadily depopulated rural Tibet, but without an obvious long term goal. But once the assimilationist erasure of minority identity was public, it was easier to see what all 16 lead to: a high energy civilising mission, to urbanise the Tibetans, turn them into a Chinese speaking workforce in the factories moving west, far inland, that rely on extracting raw materials from Tibet and eventually, Tibetan employees.

PURGING THE MIDDLEMEN

Overt assimilation of all nationalities into the singular Zhonghua race could not be announced until the bureaucratic apparatus of regional autonomy, especially the many cadres, local officials and United Front Work Department apparatchiks from various nonHan ethnicities, were purged. The CCP had recruited many minority ethnicity leaders, while never fully trusting them.

Purges have been important within the CCP since its’ founding over a century ago, essential to maintaining tight central control, and a consistent ideological line.

Ray Wang 257: “The centre of this strategy is party-building (党建, dang jian), a principle that emphasises the centrality of consolidating power and the command chain within the regulatory system. As Mao’s famous phrase goes, ‘dasao ganjing wuzi zai qingke’(打扫干净屋子再请客, ‘Clean up the house and then invite and treat’). After a series of anti-corruption purges that began in 2013, Xi had gradually put his own people into every department of the party and government ministries. However, he could not yet be sure that these appointees would do his work, especially the difficult task of cutting ties with the religious establishment and seriously implementing the old red line policies. In the regulation of China’s religious landscape, the PLAC is generally used to identify and repress a relatively small number of disobedient activists in the religious black market. It is the CCDI’s function to prosecute the few party cadres who have continued to maintain improper involvement, those who have in essence failed to clean their hands upon removing them from the black and grey market cookie jar.”[15]

The cookie jar was intrinsic to the large bureaucracy that ran the “autonomous regions”, both a party bureaucracy -the United Front Work Department- and a state bureaucracy -the State Ethnic Affairs Commission.

The party-state needed locals as brokers, go-betweens, compradors, fixers, somewhat akin to the tusi of earlier times, through whom indirect rule of frontier regions was administered. In a country where everything is achieved through favours, a dense network of minzu brokers was essential, through the decades after Mao and before Xi Jinping. Tibetans learned from their Han masters that a job in one of these bureaucracies is the only secure lifelong employment, an iron rice bowl in an insecure world.

Prior to Xi Jinping the policy was to recruit as many minority ethnicity folks as possible to the party-state apparat, partly by awarding an extra 20 points on the crucial gaokao exam to minzu applicants. This was standard diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) strategy in universities around the world, and hated by Han, who resented the favouritism of DEI.[16]

The networked minzu brokers maintained a status quo, whether for their own benefit, their clan, or the party-state, or all three. They softened the impact of top-down policies. They reported up the line what higher levels wanted to hear. They were essential to a system that was meant to bring investment, development, modernity, prosperity to remote districts, often by pairing rich coastal provinces with poor deep inland provinces. Who you know mattered a lot.

Tibet Policy Institute tracks the purges: https://tibetpolicy.net/major-leadership-reshuffle-in-tar-in-run-up-to-the-20th-party-congress/

Collective Leadership System in CCP may Resume after Xi Jinping’s Ten-Year Term

A NEW URGENCY

Under Xi Jinping, security rose to be more important than development. Controlling risks was paramount if the CCP was to fully complete its transition from revolutionary to ruling permanently. Xi Jinping brought a new urgency to the slow process of integrating the minorities. There was no longer time for gradualism.

Securitising the buffer zones of the far west, China’s gateways to central Eurasia and South Asia, was essential. A more directive, command-and-control policy was essential, enabling China to concentrate its force projection power eastwards, out into the Pacific, to threaten Taiwan, without having to worry about securing the far west. It should be all quiet on the western front.

An accelerated forced march into assimilation was required, to deal once and for all with the scourge of separatism, and identities bound up with deep cultural ties beyond China. One unitary nation-state, speaking one language, one race.

What triggered this urgency was not the revolt of the Tibetans in 2008, quickly erased as China celebrated staging the Olympic games a few months later. It was the revolt of the Uighurs, peaking not long after Xi Jinping took power. That is a major topic, not retold here, other than a few key aspects relevant to our focus on the current assimilation policy, in both Xinjiang and Tibet as the culmination of the many technologies of governmentality.

China’s full-scale punitive detention of Uighurs, in concentration camps built to forcibly “de-radicalise” Uighurs took years to build, further years to function at maximum intensity, then revert to a semblance of normalcy in recent years, with the assimilation policy still central. Tibet, by comparison, did not seem as uncontrollable, so mass detention camps were not needed. However in both big regions the assimilation campaign took years to escalate into full pressure to abandon group identity. In both regions assimilation policy persists, while citizens live in a superficially normal open-air prison without walls.

Governmentality insistence that there is only a single Chinese Zhonghua race continues to escalate, relegating the mother tongue to, at best, a trivial and irrational personal choice of no relevance or utility in the public sphere. The Tibetans and the Uighurs face the same relentless assimilationist pressure. China’s contribution to governmentality combines maximum pressure to assimilate with performative declamations by Tibetans and Uighurs greeting mass domestic tourists that all is well, we all love the Party, do have some of our food, may we dance for you?

In CCP jargon, purging the minzu brokers often meant accusations of corruption, but more often of “formalism”, meaning lip service to official policy from Beijing, without any enthusiasm for actual implementation.

Many mid-level career minzu bureaucrats may have been purged, eliminating internal resistance to intensive assimilation, but formalism persists. Wuhan University rural sociologist Lu Dewen 吕德文, looks at the chain of command through the eyes of local officials: “the “one-size-fits-all” policies, “technological hegemony” of third-party tools and apps, and various “red lines” and “bottom lines” that inspire fear and timidity among grassroots cadres, transforming them into little more than automatons. Most of the time, lower-level cadres are caught up in a vicious cycle of busywork. Their superiors fear that cadres at the grassroots don’t have enough to do, so they constantly assign them all manner of “bullshit work.” Their time is marked by task lists to be completed, work guidelines to adhere to, and punctuated by ad-hoc emergency memos and directives. When there are thunderstorms, they are instructed to conduct safety checks on local dwellings; during the cold winter months when people begin using radiators and space heaters, they must carry out door-to-door inspections to check for fire hazards.”

Governmentality seeks opportunity to remind citizens the state sees them, watches them, is present in their lives. What seems like “bullshit work” is intrinsic to making the state tangibly present in the lives of everyone.

Political scientist Ray Wang, of Chengchi University, tells us: “Xi’s approach is a rejuvenation of Mao’s united front concept with updated tactics interplaying brutal internal purges, intensified legal regulations and a steroid-injected party organ for its implementation. Cleaning one’s own house is the top priority and is highly characteristic of this process. The cross-removal campaign and radical anti-extremist campaigns show that Xi was dissatisfied with the old United Front arrangement represented by the ‘Wenzhou Model’ in Zhejiang and the ‘united multi-ethnic state’ in Xinjiang, and his lieutenants were eager to create new methods to flush out incompetent cadres and impudent religious and minority elites, in order to keep potential social resistance at bay. The new cadres and updated standards were followed by new laws, programs and concentration camps and the rest is history.

https://tv.cctv.com/2024/09/26/VIDEI5HU5w03RmU9wtxqrOm3240926.shtml

“We continue to see Xi’s officials taking group pictures with pastors and monks, attending grand religious ceremonies and funding conferences and summits as long as they help out the party’s Great United Front on such issues as Tibet, Xinjiang, Hong Kong and Taiwan, or foreign policies like the Belt and Road Initiative. At the same time, its core doctrine, which had been much more tolerant and flexible in the Deng, Jiang and Hu eras, has been replaced—the party is now above all. Furthermore, the Great United Front is ‘greater’ because its responsibility now knows no bounds. United Front cadres who used to consist more of educators, researchers and conference organisers in relevant fields are now also taking the lead in maintaining community security, persecuting defiant participants and monitoring hostile overseas individuals and groups. In other words, Xi’s China is less preoccupied with boosting its popularity than with eliminating threats to its legitimacy[17]

OUT WITH AUTONOMY, IN WITH UNIFORMITY

James Leibold, who for decades has tracked China’s changing policies towards difference, diversity and minorities, describes the 2024 situation: “Another cultural revolution is in full swing in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). This is not the purported class revolution Mao advocated in the past, but rather a wave of Han cultural and racial nationalism.

“Xi’s new approach to ethnic minority policy repudiates the Party’s past promise to allow minority nationalities to exercise political and cultural autonomy, becoming “masters of their own house.”

“Following more than ten years of incremental change, a new textbook from scholar-officials articulates the discourse, ideology, and policies associated with a new Han-centric narrative of China’s past and future.

“In this conception, the sovereignties and homelands of the Tibetan, Uyghur, Mongol, and other indigenous minorities are erased and replaced with a seamless teleology of the Han colonial and racial becoming.”

This is the culmination of the technologies of governmentality.

[1]Lawson, J. (2011). Xikang: Han Chinese in Sichuan’s Western frontier, 1905–1949. PhD thesis, Victoria University of Wellington

Stéphane Gros, ed, Frontier Tibet: Patterns of Change in the Sino-Tibetan Borderlands, Amsterdam U Press, 2019

Wang Xiuyu, China’s Last Imperial Frontier: Late Qing Expansion in Sichuan’s Tibetan Borderlands. Lexington Books, 2011.

[2] James C Scott, The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia, Yale 2009

[3] Thomas Heberer, Social Disciplining and Civilising Processes in China: The Politics of Morality and the Morality of Politics, Routledge, 2024, 94

[4] Ivan Franceschini, Nicholas Loubere, Bending Chineseness, Made in China journal, VOLUME 9, ISSUE #1 JAN–JUN 2024 https://press.anu.edu.au/publications/journals/made-china-journal/made-china-journal-volume-9-issue-1-2024

[5] Fitzgerald, C.P., The Southern Expansion Of The Chinese People. “Southern Fields and Southern Ocean”, ANU Press, 1972

Richard von Glahn, The Country of Streams and Grottoes: Expansion, Settlement, and the Civilizing of the Sichuan Frontier in Song Times, Harvard, 1988

[6] Yan Sun, From Empire to Nation State Cambridge University Press, 2020, 52

[7] James MacGregor and Ced Hesse, Pastoralism Africa’s invisible economic powerhouse? World Economy · January 2013

[8] Kenneth Edward Linden, Milk Is Gold: An Environmental And Animal History Of Livestock Herding In

Socialist Mongolia, PhD thesis, Indiana, 2022now

[9] A. H. Rasmussen, The wool trade of Northern China, Pacific Affairs, 9 #1, 1936, 60-68.

H Lee Shuttleworth, A wool mart of the Indo-Tibetan borderland, Geographical Review, 13 #4, 1923, 552-558 Downloadable via JSTOR.

H.D. Baker, British India, US Department of Commerce, 1915

C.E.D. Black, The trade and resources of Tibet, Journal of the East India Association 41 (48), 1908, 1-26

W.S. Hamilton, Notes on Tibetan trade, Government of Punjab, 1910

Luc Kwanten, Indian trade marts in Tibet, Courrier de l’Extreme Orient, Brussels, 3 (29), 1969, 45-53

Trade with Tibet, Indian trade journal, 6, 1907, 610-12 and 728-9; and 8, 1908, 344-5

[10] Chenrun Sun, Zhaohui Xue , Ling Zhang, and Hongjun Su, Local Peak Savitzky–Golay for Spatio-Temporal Reconstruction of Landsat NDVI Time Series: A Case Study Over the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau, IEEE JOURNAL OF SELECTED TOPICS IN APPLIED EARTH OBSERVATIONS AND REMOTE SENSING, VOL. 17, 2024 13439

[11] Michel Foucault, Security, Territory, Population: Lectures at the Collège de France 1977–1978 , trans. Graham Burchell. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007, 108, 247-8

[12] Todd May, Governmentality, ch32 in The Cambridge Foucault Lexicon , 2014

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139022309

[13] Michael Hechter, Alien Rule, Cambridge, 2014

[14] Lu Dewen—“Bureaucratic Formalism Has Made It Impossible for Local Cadres to Get Anything Done”, China Digital Times, 27 Nov 2023

[15] Ray Wang, Sinicisation or ‘xinicisation’: Regulating religion and religious minorities under Xi Jinping, ch 10 in Ben Hillman ed, Political And Social Control In China: The Consolidation Of Single-Party Rule, ANU Press, 2024 free download: https://press-files.anu.edu.au/downloads/press/n12044/pdf/ch10.pdf

[16] James Leibold, Han Chinese reactions to preferential minority education in the PRC, in James Leibold ed, Minority Education in in China: Balancing unity and diversity in an era of critical pluralism, Hon Kong University Press, 2014, 299

[17] Ray Wang, Sinicisation or ‘xinicisation’: Regulating religion and religious minorities under Xi Jinping, 271, in Ben Hillman and Chien-Wen Kou eds, Political And Social Control In China: The Consolidation Of Single-Party Rule, ANU Press, 2024, free download