EUROPE’S ENGINE

European car makers have no idea what’s coming.

The affordable Chinese electric cars about to flood the European market will upend a business model that sustained Europe for a century. Euro auto is on course with European mammoths and rhinos, for extinction.

It’s not just the tech revolution, the switch from internal combustion to electric, that they failed for far too long to adopt. It’s more than the arrogant insistence that internal combustion is here forever, with emissions tests rigged to fool laboratory emissions testing. Bad as that dieselgate scandal was, it signalled an abiding deafness to the prospect that the core competence of Europe could be supplanted.

Foundational to that complacency is the assumption that European smarts will always be ahead, even when imitated in obsessive detail. Imitators will always struggle to keep up the pace set by innovative Europe, especially its German engine.

The electric cars about to sweep Europe will rapidly shatter those patriarchal delusions, as only a late entrant backed by a developmentalist state can do. A famously patriarchal Australian prime minister announced “every man is a king, in his own car.” That assertion of the sovereign individual, beholden to no-one, is today matched by the smugness of the Euro car makers. So yesterday.

What the car manufacturers simply haven’t noticed is that the Chinese have learned all too well from contemporary neoliberal capitalism that it’s no longer what is under the hood that matters. Indeed it’s not the car, that gets you from A to B, that matters any more. It’s all about the interior. It’s all about the endless proliferation of desires the car interior designers can pack in, making each seat an arcade of endless entertainment choices, infinitely variable, endlessly programmable to project to the world outside your impeccable taste, your values, your irresistible smarts.

INVENTING NEW HUMAN DESIRES

Getting into the new cars about to flood Europe is like living inside your smart phone. Only by playing with the endless possibilities do you discover each feature, how each gesture opens up yet another universe. Truly China has learned so well from its shotgun marriages to the best in the Euro business, learning not only to own and patent the electric battery game, but above all create an interior Disneyland with more features than your home entertainment centre, more internet-of-things connectivity than the smartest of smart homes.

Getting into the new cars about to flood Europe is like living inside your smart phone. Only by playing with the endless possibilities do you discover each feature, how each gesture opens up yet another universe. Truly China has learned so well from its shotgun marriages to the best in the Euro business, learning not only to own and patent the electric battery game, but above all create an interior Disneyland with more features than your home entertainment centre, more internet-of-things connectivity than the smartest of smart homes.

This is the genius of capitalism; inventing wants no-one knew they wanted until the tech landed; then turning wants into desires, and desires into needs. China learned all too well. Now the world is learning the hard way it must learn from China. Now we have economists bluntly saying to beat China, you must become like China.

If this all seems hyperbolic, wait till you do get to sit inside a new Chinese made electric car, and not only in the driver’s seat. Until you get opportunity to do that, here is an enthusiastic reviewer, to show you round. Our guide on this road trip is a king among key online leaders (KOL), the grand title China gives to its top influencers. Come to California, to meet Doug de Muro.

The dominant Chinese electric car maker, BYD, knew what it was doing when it shipped its car to Doug, even though BYD has no plans to sell its cars in the US, and is instead intensely focused on cracking the Euro market. Doug takes almost 30 mins to marvel at all the wonders BYD has wrought. His listing of how passengers call the shots goes on and on. This is a gleaming man cave with every feature you ever imagined, plus a whole lot more you never even thought of.

MEETING THE HAN

This is the BYD Han. The Chinese character Han 汉is right there in the middle of the steering wheel. Like the name, not subtle, just loaded with gizmos. For instance, in an instant you can go into “turbo mode”, not to hype up the actual engine, but to make your gaming computer screen faster. As for the actual speed of the motor, there is a chrome badge on the back announcing this is the Han 3.9S model, meaning it accelerates from zero to 60 mph/100 kph in 3.9 seconds, pretty cool, just what a sovereign man wants, leaves everyone to bite my dust.

Doug’s enthusiasms burble on, too many to list here. Just a few: how would you like the rainbow spectrum of ambient lighting to pulse to the beat of the music coming from your infotainment system? There’s a button for that. Each passenger has their own climate controls. All seats are stitched leather. The big infotainment screen has its own electric motor so you can toggle between landscape horizontal or portrait vertical, like your smart phone. Totally personalisable.

It’s the back seat experience that drives this car, it’s your car, you are the boss man who, being in the back seat is clearly in charge, while the human driver is just a gig worker needed only as long as it takes to fully automate to driverless. This too is something we are just starting to realise we can learn from China, though Buick learned this long ago.

UX: USER EXPERIENCE

The experience of being cocooned and in command is all. Another KOL (key online leader) focussed solely on the Chinese auto market, Tu Le, reminds us of what we really need to know, which anyone watching car ads already half knows: It’s not about the car at all, least of all the mechanicals, it’s all about experience of the car as prosthesis, extending your reach, making your statement, declaring your values, becoming the cyborg. Tu Le says “how, how did they get so far ahead and, and how do we catch up? Because most executives, most automotive, traditional automotive executives have no idea about software and hardware, software integration. And so, and user experience, because most automotive companies, their products are product focused, whereas tech companies are user focused. Traditional automotive is just very slow, product life cycles of 5, 6, 7 years. Whereas every tech product you get is new every 10 to 14 months.”

This is why the European carmakers are facing their existential moment. Electric versus fossil fuel combustion is just the start. This is the internet of things on wheels and the only way to survive is to become more Chinese, starting with thinking like a tech startup, not a capital-intensive heavy industrial manufacturer. Dude, this is the fourth industrial revolution on wheels.

Tu Le, proprietor of China Auto Insights, and his interviewer Bill Bishop put this down to Pax Americana complacency, as if the Japanese car makers 30 years back, or the Koreans 20 years ago, hadn’t done much the same. But America is furious that its Chinese car builders learned their lessons all too well, and has now, far too late, slammed the door.

CHINA’S BUSINESS MODEL: CHINA.INC

That leaves Europe, hoping for the best, unprepared for the worst. What Europe is least prepared for is China’s statist, developmentalist model of industrial policy, with state owned enterprises in the lead. Since the national champions have the active support of the central party-state, they can go all out to achieve their goal of market power, including oligopolistic market dominance. If that means ruthless price cuts to get market share and bankrupt competitors, they will do it, for China’s greater glory. They are too big to fail and can always be bailed out. The closest European parallel might be Hitler’s national champion, Volkswagen in the 1930,.

That leaves Europe, hoping for the best, unprepared for the worst. What Europe is least prepared for is China’s statist, developmentalist model of industrial policy, with state owned enterprises in the lead. Since the national champions have the active support of the central party-state, they can go all out to achieve their goal of market power, including oligopolistic market dominance. If that means ruthless price cuts to get market share and bankrupt competitors, they will do it, for China’s greater glory. They are too big to fail and can always be bailed out. The closest European parallel might be Hitler’s national champion, Volkswagen in the 1930,.

Developmentalism, like all -isms, is an ideology. Development, narrowly defined as economic growth that ignores environmental destruction and human displacement, becomes the ideology of the developmentalist state, a state fixated on catching up with the richer countries, by whatever means necessary. The developmentalist state distributes wealth to its cronies, is unafraid to pick winners, exercises much greater command and control powers than democratic states constrained by popular opinion. Developmentalist states do whatever it takes to industrialise, urbanise, accumulate and concentrate wealth, investing more and more in more industrialisation, usually by predatory taxation of the poor, money which the developmentalist state then allocates to its favoured industry champions. The result is monopolies.

SAGE DADDIES

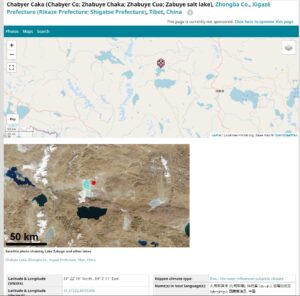

In a race towards monopoly, there will be losers, there must be. Warren Buffett, the great sage of Omaha, himself an advocate of market power, foresaw all this when he and Bill Gates benevolently declared a Tibetan salt lake to be BYD property, way back in 2011. Under a banner reading “Let innovative New Energy technology power the philanthropic light in Tibet and the World.”

Back then it might have been new, now this “philanthropic light” is standard operating procedure. The phase of market acceleration and dominance has arrived, with Chinese statist characteristics. Buffett and Gates could proclaim themselves philanthropists, although Buffett’s investment in BYD earned him billions. Buffett has been shining that light on Tibet ever since.

Did they know they were sowing seeds of an imperial competition? China flattered Buffett and Gates and many mentors, all the while learning not only how to make The Machine, but also whatever it takes to dominate the market. China learned from Japan and Korea and Taiwan that a powerful developmentalist state, unafraid to allocate capital to winners, can deploy industry policy to ensure your favoured SOEs do become national champions and launch into the sea of global markets. Little wonder Europe struggles to compete.

Did Elon Musk care when, in 2019, at the pinnacle of President Trump’s anti-China tirades, he announced a Tesla mega factory would be built in Shanghai, and lo! It came to pass.

WHO’S ON NEXT?

Thus, we arrive in the present. America insists it is in the driver’s seat, in command. China is in the back seat, yet in command. Something will soon move fast, then break.

The BYD Han is designed to compete with the Audi A6, the Mercedes E class, or Lexus, Doug de Muro tells us. These are upmarket high-performance cars with luxe interiors to match. Usually around $80k. Hand-stitched leather is expensive.

If BYD sells this car in Europe, builds car factories, battery factories and charging stations all over Europe, it could compete with Audi and Mercedes on both quality and price. But what if BYD, to secure market share, also slashes prices?

It can afford to, since it is vertically integrated, owning the Tibetan lithium mines, the ore processing, the metals purification, the fabrication of batteries, and the car wrapped round the battery. All aspects of the supply chain are inhouse, with the possible exception of advanced computer chips.

If a period of losses is needed, in order to establish market dominance, BYD can handle it much better than Daimler shareholders will. The party-state is guarantor and cannot let the big electric car makers fail. There is simply no European equivalent, and for decades the EU has shunned the idea it might pick winners.

PRICE WAR

Whether BYD might slash prices is not a theoretical possibility.

BYD’s sudden price slashing, in its home market in 2023, took everyone by surprise. The conventional narrative was that China’s electric car market -by far the biggest worldwide- is fragmented among foreign and domestic manufacturers, no clear winner, time will tell who comes out on top. The big global brands are all heavily invested in China, both for its cheap labour for battery car exports, and for the size of the domestic market pumped up by direct subsidies from Beijing.

How could a company that began life as just a battery maker, suddenly slash prices at the moment it was starting at last to make real money? Just compare the BYD model launched by Warren Buffett and Bill Gates, a nondescript tin box, with today’s sleek and fast challenger to Audi and Mercedes. It’s been a steep learning curve.

For a while it looked like BYD might have carved for itself a viable market segment by making buses, especially the short haul buses that shunt airport passengers and then return to base, to recharge. Airports worldwide bought them. But that was just a stop en route. All along, BYD never forgot that its surname is Party, and the party-state strategically pumped the market demand with selective subsidies. There is no European equivalent, although the 2008 US rescue of Ford may come close.

BYD’s first models were ugly, anonymous knock-off clunkers. But they knew user experience is everything, nothing much else matters as long as the battery is big enough to make the car go zoom, zoom. BYD knew how to think like a tech company, not a complex combustion engine company, and they knew from the start that like phone app designers, it’s all about inventing new human desires. Warren Buffett saw this and swooped.

BYD foresaw this fourth industrial revolution, whereby a battery manufacturer could one day become a car manufacturer, since the battery in an electric car is by far its biggest, most expensive and heaviest component, unlike the complex and cumbersome internal combustion engine. Once you can make the batteries, including buying exclusive rights to Tibetan lithium rich salt lakes, all you need is to learn how to wrap a car round it. That took several years, during which Warren Buffet saw his stake value grow and grow.

Now 2023 BYD has models that compete with Audi and Mercedes $80K models, and swoops on Europe. If that means price cuts big enough to destroy Audi and Mercedes, the developmentalist party-state stands with them, with an armamentarium of tools it can deploy.

IN CHINA, THE EUROPEANS ARE TANKING

To everyone’s amazement, in 2023, the bottom dropped out of China’s massive electric car market for nonChinese brands.

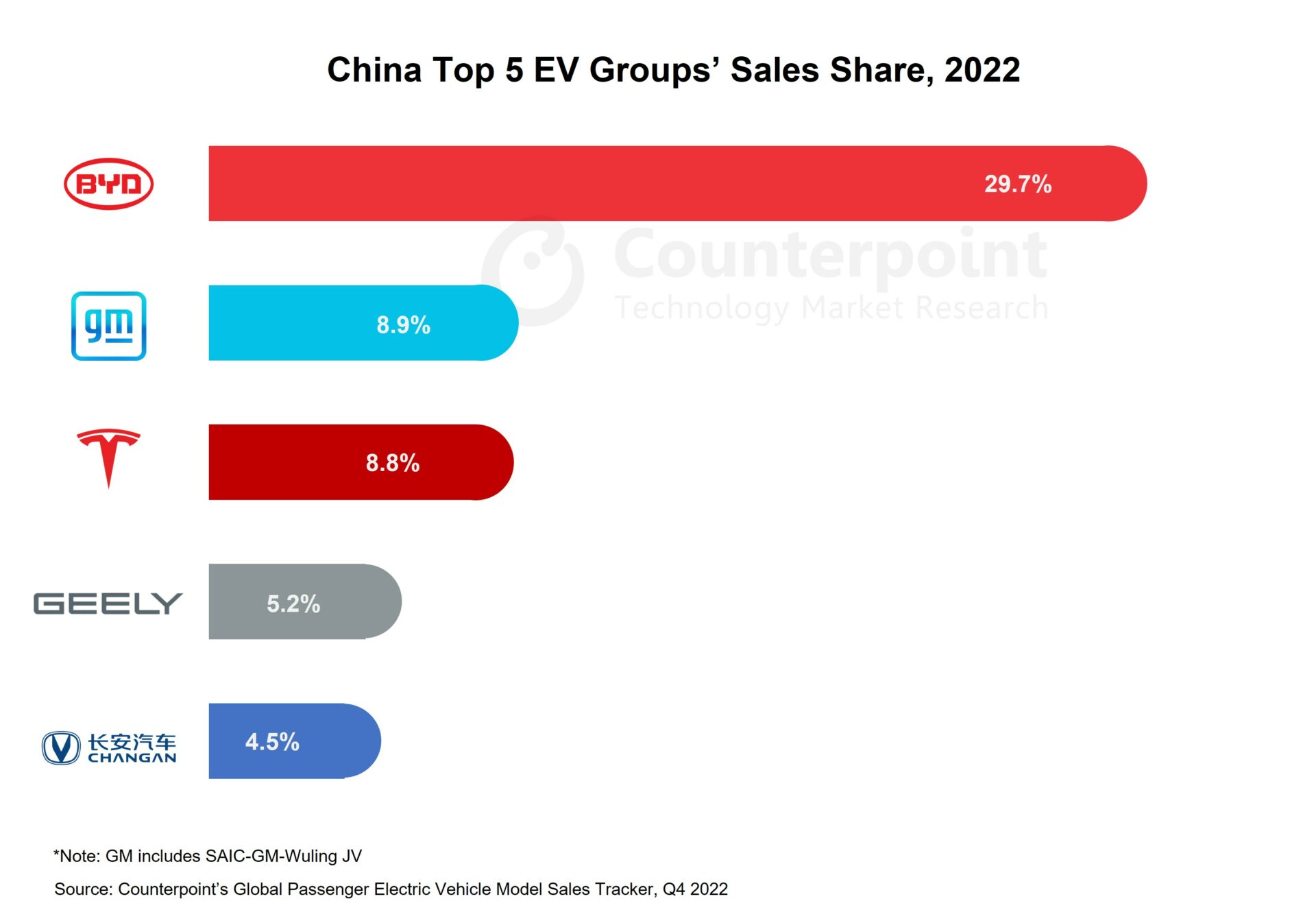

Should we be surprised? Deploying patriotic Sinocentrism is the hallmark of the party-state and all of a sudden foreign brands are shunned, while BYD surges past Tesla and all other rivals, for top spot in China.

Is the same likely in Europe? BYD is now so dominant in China, and so highly profitable, it can withstand a price war. Caixin: “Warren Buffett-backed Chinese electric-car maker BYD Co.’s profit surged 411% in the first quarter, boosted by EV sales growth that beat the industry average. Operating revenue rose 80% to 120.2 billion yuan ($17.38 billion) while the gross margin was 17.9%, up about 5.5 percentage points, the Shenzhen-based automaker said Thursday. In the first three months of 2023, BYD sold 552,100 new-energy vehicles (NEVs), almost double from the same period a year ago. NEVs include hybrids and purely battery electric autos. BYD accounted for more than a third of the country’s total NEV sales. China’s total NEV sales increased 26.2% to 1.6 million units in the first quarter, according to the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers (CAAM). BYD aims to sell 3 million EVs this year, compared with 1.86 million in 2022, the company said earlier this month at the Shanghai Auto Show. The company’s high gross margin means it has more room to lower prices amid tougher competition and a price war after waning subsidies and a shaky economy weakened demand. At an investor event April 13, BYD said it will press the “fast-forward button” in its overseas strategy this year.”

In China this latest iteration of the BYD Han sells for no more than $43 k for the fastest model with the biggest battery, capable of doing over 700kms without recharge. The cheapest Han is $30k. Already, those prices are half, or less, of its’ Euro competitors. Stitched leather? Classy.

HYPER SPEED MODE

Now BYD has pressed the fast-forward button (it used to be called the accelerator pedal). Sometimes a Han’s gotta do what a Han’s gotta do, even if it brings down some pillars of China’s premium pillar industry. After all, as many as 300 Chinese companies announced they were in the electric car business. If a battery maker can make cars, why not a real estate developer, or anyone chasing fast money? Time to crash a few pillars. Anyway, it was Tesla that started the price war.

Now the entire Euroamerican car industry is abruptly awakening to a new dawn. The Financial Times puts it plainly: “When a market turns against you, how should businesses respond? This is the question being pondered with some urgency across the automotive boardrooms of the world. The market is China, the world’s largest auto market. It was once the breadbasket of the industry, flush with a hugely profitable pool of newly-wealthy consumers, many of whom were eager to flaunt their status with a shiny Mercedes-Benz or Buick. The entry price for overseas carmakers — a technology-sharing joint venture with a local manufacturer — seemed worth every yuan. But the tide has turned. The build quality of the Chinese brands have caught up with global nameplates, no doubt aided by the experience of running joint factories. And inside the vehicles, the technology — the key to unlocking the hearts of Chinese consumers — is now superior. Whether the touch screen systems, the connectivity, or the batteries themselves, many of the Chinese-made models are now considered comparable, if not better. Nissan’s chief executive Makoto Uchida admitted last week that local brands were moving “much faster than we expected before”. The question is how to respond.”

Or is it already too late? Has the sorcerer’s apprentice learned all that is needful for mastery, right down to the last luxe cured cowhide stitch? Is China no longer biding its time, but revealing its strength, nurtured by those decades of mandatory technology transfer from Europe’s car makers to the Chinese? Are we now in the world of Faust? Nameplates don’t work as shields.

The only option left, for “legacy” car manufacturers, is to now learn from the Chinese.

Ford chief advanced product development and technology officer, Doug Field, said that Ford’s approach to creating EVs is radically different from its traditional strategy for vehicle development, emphasizing that software will define and control many new features – including features Ford hasn’t yet developed, but will add to existing vehicles in the future via updates. “The products we make are not living rooms. They are moving, working robots. And our software ambition goes way beyond deep into how our products move, how they collect data, and how they support people who are going to use them for real work. We call them unimaginably great products, because the best things we will make are the ones we haven’t thought of yet.”

VERTICAL INTEGRATION BEGINS WITH TIBET

In a decoupling world beset by supply chain glitches, logistics jams, sanctions, mercantilism, chip shortages and unconscionable conduct, BYD stands out because it is so vertically integrated, all the way from a Tibetan salt lake in the remotest corner of the alpine deserts of upper Tibet, through to the glittering showroom floor.

That’s a business model that was supposedly superseded, by smarter, leaner, just-in-time globalised, super-efficient commodity flows, involving myriad parts makers, supplying their specialty component at just the right moment and right price. The big corporations with the big brand names, from smart phones to electric cars, simply assembled it all, and put their badge on it. From big pharma to big mining as well as computers and phones, the vertically integrated corporate giant seemed to belong in the past, a dinosaur too big and heavy, too over-capitalised to survive today’s nimble corporation.

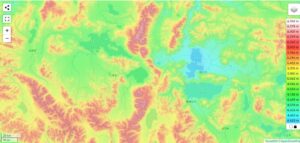

How times have changed, yet again. BYD’s claim to own the purest lithium lake in Tibet was foundational to its success, back when it impressed investors, Warren Buffett among them, that it had exclusive access to Zabuye Lake (Drangyer Tsaka in Tibetan) in a location no-one could then find on a map. Who knew or cared that from this lake of pure lithium salts it is 1000 kms on bad roads to Lhasa? More than 2000 kms to any industrial location capable of processing and utilising the lithium?

TO OWN THE MARKET, FIRST OWN TIBET

Until recently, there was confusion as to how much Tibetan lithium is in industrial use, as China reached out instead to the “lithium triangle” of the alpine deserts where Chile, Argentina and Bolivia meet. The confusion arose because in the most accessible salt lakes of Tibet the lithium is mixed in with other salts, of sodium, potassium and magnesium, and very hard to separate, then purify to a standard high enough for batteries that don’t overheat, lose their charge, or even catch fire. In S America, no such complexities. Only in far western upper Tibet is chemically pure lithium plays, and the Chilean lithium triangle. They are much simpler, easier to obtain battery-grade pure lithium.

Due to this confusion, it has been hard to be sure that China’s dominance of the lithium battery and electric vehicle industries are definitely reliant on lithium from Tibet, even though it looked like China might solve the purification problem. Then, in 2022, the lithium price soared, resulting in a corporate scramble for Tibetan rock lithium as well as salt lake lithium. There is now no doubt that Tibet is core to China’s dominance of the fourth industrial revolution.

Lithium is not the only metal extracted from Tibet that China relies on to establish its global power.

Copper, molybdenum, chromium and magnesium are just as important, all sourced from Tibet. Taken together, these five metals are foundational for China’s ambitions, and unlike China’s mines in Chile, Peru, Congo or Zambia, the deposits are domestic, entirely at China’s disposition.

All five critical minerals are sourced from China’s Tibet, all are foundational to China’s developmentalist path of infinitely expanding human desires, wants and needs. They are essential to realising the Chinese dream. As globalised commodity chains get riskier, more vulnerable to disruption, despite rapidly rising demand for these raw materials, Tibet becomes more important to China, not only as a security barrier and environmental barrier, but as an archipelago of enclaves of extraction.

LEAPING INTO THE PASSING LANE

Japan in the 1980s did for a while seem to be in the passing lane, leaving America behind, likewise Korea a decade or so later. Then they settled into a middling role, with substantial niche markets in the auto trade worldwide. China, however, is determined to be different, to wholly fulfil its deeply rooted ambition to overcompensate for a century of humiliation, grow as rich as the richest of emitters, and then keep going, with 2049 the target date for attaining a materialist utopia. China’s emissions reduction goals in no way limit the developmentalist trajectory of endless growth, if anything they drive it. China is intent on having it all.

They key is the capacity to contrive new human needs, out of nothing. This is what the apprentice learned so well from the sorcery of consumer capitalism, and the electric car boom, along with solar and wind power and “green” energy, are tickets to ride, all the way.

DREAMING ON AND ON

This is the Chinese dream, of growth without end, boundless material fulfilment, and all of it badged “green”. Building that dream is actually work done by the anonymous mass of rural Chinese who work in the factories assembling the BYD Han, who could never afford to buy what they fabricate, until the assembly line is fully robotised. Seldom do we get more than a staged glimpse of the assembly line, since no-one has much interest in peasant families torn apart by city factory work, sleeping in bunk beds in mass dorms. We never see the work that is hardest to automate, the precision hand-stitching of those cowhide leathers into luxe seats.

Building the Han dream is magic. The car appears. We sit behind it at the traffic lights. On its rear the chrome-plated reminder the name of the model is 3.9 seconds. Above that, stretched across the back, each chromed letter separately affixed to the trunk, is the punchline: BUILD YOUR DREAMS.

BYD started life decades ago as a battery maker, adopting a three-letter name with no meaning, easy to say, vaguely sounding a bit like Peking University in Chinese. Intrinsic to BYD’s rise was the invention of “build your dreams” as the true meaning of those bland corporate initials. As intellectual property, that slogan is probably worth more than all the lithium in Tibetan salt lakes, but both are essential.

So too is the chromium from Norbusa, near Tsethang in southern Tibet, that makes those letters gleam. Chromium is much used in making cattle skins into fine leather. All are ingredients of building the Han dream.

No-one pays much attention to the copper, lithium, chromium, molybdenum and magnesium that constitute a Han car, sourced from Tibet. All interest is on the gleaming result, a Bildungsroman announcing China’s maturity on the global stage, arriving fully formed, an infotainment world on wheels. The Germans, who invented the Bildungsroman as an edifying story of growing into moral and psychological adulthood, are in for a shock. Make way for the Han. It’s comin’ at ya.

CHINA BUILDS DREAM CARS, AMERICA BUILDS WALLS

While the BYD Han and other Chinese electric vehicles may eventually dominate the Euro car market and car industry, no such challenge is likely in the US. There China bides its time, acutely aware America is in no mood to admit anything like parity with China. The US frames this as a global clash of civilisations, of the democratic world versus the autocratic world, a framing that collapses into incoherence when you look more closely at who the US counts as its friends. As Foreign Policy journal says: “Regrettably, the Biden administration does not have a China policy—it has several that often conflict with one another. At times tough but typically conciliatory, the administration’s flawed competition framing confuses means with ends, dodging altogether the difficult task of defining the United States’ desired end state vis-à-vis China.”

China’s stinging accusation is that the US refuses to share power and denies the reality that a unipolar era is ending. History is full of empires that fell apart. The metropolitan elites of London, Paris, Brussels, Lisbon, Istanbul and Moscow are still, a century later, struggling and conflicted over accepting their losses. Now it is the US, fixatedly depicting China’s rise as Sparta’s war against Athens, due for an inevitable grudge rematch.

In reality China and the US are startlingly alike, especially in their embrace of market capitalism, wealth concentration, mass precarity, worship of billionaires and tech entrepreneurs, consumption as the purpose of life. What unnerves the US is how damn good China was at learning from America, exemplified in one gleaming package, the BYD Han. The Chinese and American dreams converge to Build Your Dreams.

By 2025, in Europe, much will be so different. The car industry is at the heart of Europe’s belief in itself as the epitome of civilization. Vorsprung durch Technik, leaping forward through technology, is Audi’s global brand strapline, protected by a seven-year battle in the European Court of Justice as exclusive to Audi. What if BYD Technik appeals more to German drivers, kings in their own rolling infotainment, and at half the price of the equivalent Audi? Where does that leave Audi, and its Volkswagen parent, and Germany, and Europe? Will Europe go the way of the US and clamp the wheels of the BYD Han? Will it be too late?