\METOK མེ་ཏོག་རྫོང་། / MOTUO 墨脱

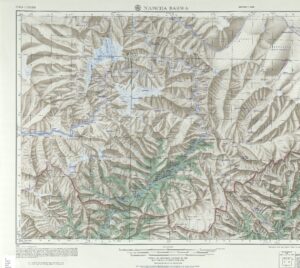

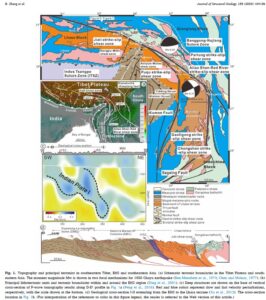

Of the many locations worldwide almost no-one has heard of, few are named in media worldwide as often as Metok མེ་ཏོག་རྫོང་། / Motuo 墨脱. This is puzzling, since Motuo 墨脱, a pinyin Chinese mangling of the Tibetan Metok, remains end of the line, the very last of China’s 1350 counties to be connected to China. Metok means flower, a clue to its wet tropics climate on a corner of a Tibetan Plateau better known for cryosphere cold. Outlier in every way, it was a matter of China’s national pride that Metok མེ་ཏོག་རྫོང་། / Motuo 墨脱 be reachable by road, achieved only a decade ago by drilling and blasting the surrounding mountains of the eastern end of the Himalaya, enabling this remotest outpost of China’s reach to be harmonised. The road access tunnel is half way up Namche Barwa mountain, the axis of the syntaxis on which Eurasia pivots.

WHERE IS THE PLAN? WHERE ARE THE FACTS?

There is now very little sign of detailed feasibility planning for a mega dam in the decades since China’s early, revolutionary enthusiasm, now 40 to 50 years ago.

However the prospect of a massive dam, just above India and Bangladesh triggers great anxiety among India’s geostrategy community. So China’s soft power projection media frequently make noises about this dam as imminent, much to the amusement of China’s misinfo/disinfo apparat, who then sit back and watch the paroxysms of fear unleashed. That is what happened on Christmas Day 2024, when China’s official Xinhua news agency announced, in English and not in Chinese that “The Chinese government has approved…” the mega dam.

To say this vague announcement went viral is an understatement. Without fact checking , this Xmas gift from the propaganda machine was taken as factual, succeeding far better than previous reiterations of the same untruth over the previous decade.

By early 2025 Metok མེ་ཏོག་རྫོང་། / Motuo 墨脱 was named by the world’s mainstream media, by geopolitics think tanks, by environmental advocates, in several languages, as the location of the biggest hydro dam the world has ever seen, newly “approved” by China. The media and the pundits did no fact checking of this repeated information warfare trope, which this time round generated more coverage than previous balloon floats by China’s soft power influence machine.

Notably missing in action was any checking on who, in China’s rigid party-state hierarchy is the mega dam’s daddy, the powerful patron with enough muscle to push such a project, very expensive and in need of a dewcade of construction, through to completion. We have the example of Premier Li Peng, who relentlessly pushed the Three Gorges Dam through to completion, despite much opposition. Li Peng is now rembered worldwide as the man who ordered the PLA to shoot the masses gathered on Tiananmen in 1989, but he was determined to be remembered as the father of the Three Gorges dam, and he overcame all obstacles to ensure it is not only his legacy but also set up his red gene princeling children as SOE corporate bosses who profit from ongoing dam building, including in Tibet.

Identifying the boss patron of a project as big at the Yarlung Tsangpo dam is not an arcane question of interest only to professional China watchers; it is basic to China 101, a basic reality check the fact checkers didn’t do.

THREE TIMES AS BIG AS THREE GORGES?

This blog takes a careful look at the prospects of this mother of all hydrodams, wedged in the far end of India’s collision with Eurasia. That means reviewing the big backlog of Chinese scientific investigations of one of the most landslide-prone landscapes anywhere, also reviewing how in today’s China the biggest and most costly of nation-building projects actually happen, in a time when the frontier of national prestige has moved on from taming rivers to landing on Mars.

Maybe the fact checkers at Reuters, BBC, Washington Post, Le Monde and many more of the most reputable media were out to Xmas lunch? Quickly the mega dam became a well-known fact. No-one asked basic questions such as: which arm of the Chinese government made the announcement? When was the actual official announcement? Who is financing this expensive, complex project? Is there an allocated budget, a business case? A construction timeline? Which state-owned dam builder is in charge? Basic questions.

In reality last time the Metok མེ་ཏོག་རྫོང་། / Motuo 墨脱 dam was listed as a project to be done some day was back in 2021, as part of the very long agenda of the 14th Five-Year Plan; 2025 being the final of those five years.

However in March 2025 Premier Li Qiang delivered, at length, the official Work Report on what was achieved in 2024, and what is scheduled for 2025. No mention of this “hydropower production base” at all. Maybe it will pop up again when the 15th Five Year Plan for 2026 to 2030 is announced, hardly the first time ambitious major projects have rolled over from one Five-Year Plan to the next. Successive Five-Year Plans for Tibet Autonomous Region routinely named “pillar industries” that one day would make Tibet prosperous, to be rolled over again and again.

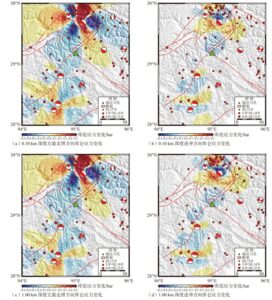

If the phantom megadam was to happen, National Development & Reform Commission would be in charge. If you search the NDRC website, both in Chinese and in English, there are a few scattered mentions of Metok, spread over several years, mentioning minor local development projects, many landslides and quakes. The most recent NDRC mention is from 2022: “Operation Bureau closely watched the 5.6-magnitude earthquake in Motuo, Tibet. On 10 November 2022, in Motuo County, Linzhi City [Nyingtri Municipality] , Tibet, a 5.6-magnitude earthquake occurred, with a depth of 10 kilometres, and the epicentre was located at latitude 28.35 degrees north and longitude 94.48 degrees east, with an average altitude of about 2211 metres within 10 kilometres, and there are no hospitals and schools distributed within the 7 degree zone, which is unlikely to cause casualties.” Small earthquake, not many hurt, small story, nothing much to see here.

Nothing on NDRC on any megadam, but plenty in praise of Siemens, a key partner for China’s long haul ultra-high voltage power grids that make possible export of electricity from Tibet all the way to China’s coastal factory belt.

NDRC also features a 2021 story, with a 10 minute professional video, on the extraction of remote Tibetan villagers from a Metok landslide-prone slope, illustrating the benevolence of China’s ongoing displacement policy: “Through the implementation of relocation, Doka village 31 households of 143 poor people concentrated relocation to more than 10 kilometres away from the Gedang Township Dolonggang village settlement, completely get rid of the dilemma of generations of poverty.”

ASSESSING THE RISKS OF A MEGADAM

In the absence of any indication of official interest in Yarlung Tsangpo Great Bend dam building, documentation and analysis of the many obstacles facing construction have gone ahead.

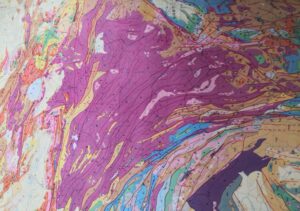

The past four decades have given other sciences time to catch up with the hydro engineering vision, to map in four dimensions the eastern Himalaya syntaxis, the likelihood of multiple disasters of a size hard to comprehend. They are our fact checkers, sobering reading.

Remarkably in 2025 the most detailed review of the practical feasibility of the Metok མེ་ཏོག་རྫོང་། / Motuo 墨脱 Great Bend dam is not any Chinese source but a 2013 personal project report by Brian Yanity, an American electrical engineer who self-published his detailed assessment. Yanity may be a lone enthusiast, but he knows his stuff. His expertise is “small-scale hydropower systems for cold-climate applications. He became involved in regional hydropower and transmission line planning while working as a consultant in the US state of Alaska, and in community and regional energy planning, including for the state government’s Alaska Energy Plan 2010. He is the author of a review of regional hydropower development strategies involving proposed international transmission lines connecting southeastern Alaska (US) to British Columbia (Canada), “Transmitting Development Strategies”, as well as a regional hydropower planning review of the Yukon River watershed in the US and Canada.”

Meanwhile China’s Ministry of Water Resources remains silent; likewise China’s many scientific journals on hydropower say almost nothing about the Metok མེ་ཏོག་རྫོང་། / Motuo 墨脱 megadam.

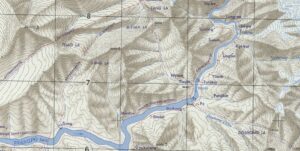

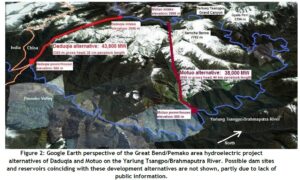

Brian Yanity’s feasibility study is thorough, as one would hope. He points out that: “While discussions in the popular press of the Yarlung Tsangpo Grand Canyon/Great Bend hydroelectric potential usually claim that such a development would involve a massive dam, the natural conditions of this particular site would allow the world’s largest hydroelectric power plant to be developed without a large dam. In theory, the annual energy generated by the run-of-river option would be less than that of a large conventional storage dam. However, since the Yarlung Tsangpo at the Great Bend carries a large amount of sediment, an impounded large reservoir of stagnant water could easily accumulate siltation to the point where water storage capacity is greatly reduced, and risk of blockage of hydroelectric plant intakes only a short number of years after the dam would be completed.

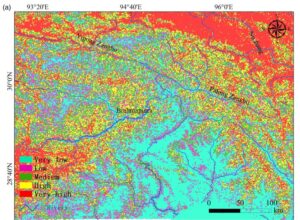

“Also, sediment deprivation downstream could be significant. Thus, a large storage dam upstream of the Yarlung Tsangpo Grand Canyon could be self-defeating enough to render itself impractical, ecologically disrupting and very uneconomical. Along with sedimentation, the greatest natural risk to any dam located in the Great Bend region is seismic activity, as major earthquakes periodically occur in Tibet. This is not surprising considering this is the location of the collision of the Indian and Eurasian tectonic plates which continues to lift the Himalayas. Local seismic risks and other geotechnical hazards specific to a particular hydropower site must be carefully studied.

“Developing the Daduqia or Metok མེ་ཏོག་རྫོང་། / Motuo 墨脱 project alternatives without a conventional large dam is an exciting possibility definitely worthy of investigation. Seismic and landslide risks would be much greater with a large dam, as is the risk of a dam failure causing catastrophic damage. The lack of a major impoundment at the Great Bend of the Yarlung Tsangpo would also help mitigate concerns of India and Bangladesh. The relatively modest size of the required dam structure for harnessing power the Yarlung Tsangpo’s Great Bend greatly improves the project’s overall feasibility.

“Therefore, the logical location of a reservoir for the purpose of power generation would only be before the river enters the main section of the canyon, at a river elevation above 2,900 m. Compared to low-elevation projects, reservoirs in high-elevation mountain areas produce much less methane emissions from decaying plant matter: alpine and subalpine vegetation does not grow and decay as rapidly as lowland forests and wetlands.

“Although China’s hydropower engineers have been quietly studying the Great Bend site for years, no official plan for development has yet been announced. So far there has been little public information released about proposed reservoir sizes and dam heights of these possible project alternatives. However, the state-owned Sinohydro company has shown a proposal for the 38,000 MW Metok མེ་ཏོག་རྫོང་། / Motuo 墨脱 alternative on its website (The Hindu, 10 June 2011). Either of these two project alternatives would return all diverted water to the river before it crosses into India. Either of the two Great Bend hydropower development options would utilize a gross head (vertical drop) in excess of 2,000 m, or higher than any hydroelectric plant in existence.”[1]

However, 12 years later Yanity’s optimism for cooperative transboundary sharing of waters and hydropower from the Yarlung Tsangpo has failed, so his map of the power grids radiating from Pemako hidden land inside the Great Bend remains a fantasy.

Since Yanity in 2013, China’s scientists have learned much more about the risks.

Today Metok མེ་ཏོག་རྫོང་། / Motuo 墨脱 remains a remote anomaly even though road access is now all-weather, due to further tunnelling of the Namche Barwa mountain, at a much higher altitude than the river diversion hydro tunnels required for any megadam. At the far end of the deep gorge of the Great Bend of the long Yarlung Tsangpo river, Metok མེ་ཏོག་རྫོང་། / Motuo 墨脱 and its modest hydropower plant is still a modest town, staffed by local government cadres experimenting, usually unsuccessfully, with banana plantations and other fruit farms. It is just too far from any market demand. Yet the vision of red plenty, of Metok electrifying China, has deep roots.

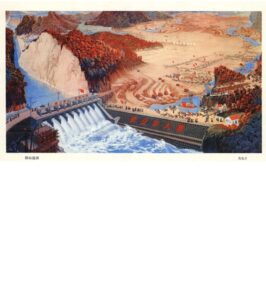

A CULTURAL REVOLUTION VISION OF DAMMING FOR RED PROSPERITY, by FATHER OF ALL MEGADAMS

A CULTURAL REVOLUTION VISION OF DAMMING FOR RED PROSPERITY, by FATHER OF ALL MEGADAMS

Many decades ago, this dramatic landscape of tropical flowers and the world’s deepest gorge understandably attracted China’s hydro engineers, proposing Metok མེ་ཏོག་རྫོང་། / Motuo 墨脱 as the ideal location for the mother of all hydro dams, capable of generating a lovely set of numbers, adding up to three times the installed capacity of the Three Gorges hydro dam on the Yangtze.

A hypnotic vision, for a China in the hands of red engineers, the same number crunchers whose extrapolations also panicked the CCP Politburo into imposing the one child policy, for many painful decades, based on their projections, their predictive assumption that, unless drastically curtailed, China’s population growth would negate all the economic growth from hydro dams and infrastructure construction, and China would remain poor. These tech heads of ballistic missile targeting -which they did well- were allowed by a PRC elite who worshipped Mr Science, to keep alive the hope of a Great Bend megadam, while policing the wombs of every fertile woman in China.[2]

Mao’s master narrative, now ingrained, self-evident, beyond debate, was that China fell disastrously behind by failing to have its industrial revolution, and so fell victim to predators. Now, China has stood up. From the outset, the revolution was about heavy industry and mining. In plays and films, the geologists and hydro dam planners who went forth into the wilds of Tibet and other remote areas beyond the frontier, were praised as exemplary model heroes, the “guerrillas of the era of socialist construction”, civilian successors to the victorious People’s Liberation Army.

One of the very few histories of the idea of the Yarlung Tsangpo Great Bend megadam dates it to 1972, the height of the Cultural Revolution’s delusional insistence that revolutionary human will conquers nature. According to a 2011 report in Southern Weekend: “Guan Zhihua 关志华 is a researcher at the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research. In 1972 the academy established a survey team to study the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau, and Guan – now in his seventies – was the head of the group charged with calculating the hydropower potential of the Yarlung Zangbo, China’s highest river. As if describing a family heirloom, he said: “The river flows for 2,057 kilometres within China’s borders, and its hydropower potential is second only to the Yangtze. It has more power-generating potential per unit of length than any other river in China.” Guan’s was the first comprehensive and systematic study of the plateau – a four year field project carried out by more than 400 people across 50 different disciplines. But the study of the Yarlung Zangbo and its tributaries was only a part of the survey, and at the time nobody had any idea of the extent of the river’s potential. The entire basin was found to have hydropower potential of 114 gigawatts – 79 of which was on the main river. And this potential was highly concentrated, with the possibility of a 38-gigawatt hydropower facility at the Great Bend in Medog county, equal in power to the Three Gorges Dam.”

In hindsight, the 1970s was the high point of China’s enthusiasm for damming the Yarlung Tsangpo Great Bend, as is clear in a 1980 public report in China’s Natural Resources journal, by Guan Zhihua: “building comprehensive water conservancy hubs mainly for power generation by utilizing the wide and narrow terrain of the Yarlung Zangbo River and some canyon sections on its tributaries is beneficial to ensuring power supply and expanding irrigation benefits. For example, the construction of such comprehensive water conservancy hubs can be considered in some canyon sections such as the Yarlung Zangbo River mainstream and the Lhasa River. In addition to having good dam-building conditions, these locations also have terrain conditions for forming larger reservoirs to increase runoff regulation.”[3]

Maybe Guan Zhihua might have done a more detailed assessment, not for public access, as neican, for insiders only. But his 1980 report reads like a basic introduction, to an unfamiliar China, cataloguing all the major rivers of Tibet, introducing them to Chinese audiences: “Since most of the larger tributaries of the Yarlung Zangbo River are distributed on the left side of the main stream, the basin area on the left bank of the river is times that of the right bank, and the basin asymmetry coefficient is . Among the major rivers in Tibet, the basin asymmetry of the Yarlung Zangbo River is the most prominent. The cultivated land and population in the Yarlung Zangbo River basin account for more than half of Tibet. Important towns such as Lhasa, Shigatse, Gyantse, Zetang, and Nyingchi are all located in the basin. Therefore, the Yarlung Zangbo River basin is the political, economic, and cultural center of Tibet.

“According to calculations, the total annual runoff of Tibet’s outflow water system is about 100 million cubic meters, the annual average flow is about 100 cubic meters per second, which does not include the water inflow from Tibet, the average runoff depth is 100 mm, and the average runoff modulus is 100 liters per second per square kilometer. The annual runoff of Tibet’s outflow area accounts for about 10% of the total annual runoff of my country’s rivers. Among them, the annual runoff of the Yarlung Zangbo River at the border is about 100 million cubic meters, and the annual average flow is 100 cubic meters per second, accounting for more than the total annual runoff of the outflow area of Tibet, and is more than 10 times the annual runoff of the Yellow River. In my country, the annual water production of the Yarlung Zangbo River is only less than that of the Yangtze River and the Pearl River, ranking third. In addition, the water volume of the Nujiang [Salween] River, Xibaxia Qu, Danlong Qu, and Zayu [Mekog] Qu is also abundant.”

The lower Yarlung Tsangpo and its sharply incising Great Bend attracted further intensive scientific quantification in expeditions from 1982 to 1985[4], four decades ago. By then, revolutionary enthusiasms of a decade earlier had evidently failed, and complexities of tectonics started to emerge.

In the years following, the more Chinese researchers explored the Yarlung Tsangpo, especially at the Great Bend canyon, the more complexity, complications and doubts set in. The turning point seems to be a further effort at scientising the Yarlung Tsangpo Great Bend, the 1996-7 expedition. Xiao Huai Yuan was one of them, and he lavishes praise on the heroic pioneers of making Tibet China’s, including Guan Zhihua: “I accompanied 12 scientists from the State Science and Technology Commission, the Chinese Academy of Sciences and other units on a trip along the Yarlung Zangbo River to conduct the first pre-preliminary investigation of the Big Bend Power Station. When we arrived at a village east of Pai Township, Milin County, there was no road, so we sat down to eat dry food. This area is inhabited by Tibetans, Monba people, and Lhoba people. A villager ran over and shouted to us: “Yang Yichou! Yang Yichou!” I didn’t understand what he said, but Professor Guan Zhihua, a water conservancy expert from the Chinese Academy of Sciences, who was traveling with me, understood and said to me excitedly: ‘He is calling Yang Yichou, among the ethnic minorities, “Yang Yichou” has become a nickname for Chinese scientists’.

“This incident deeply moved me. I have a new understanding that our scientists, medical workers, and people’s teachers are also the sowers of modern civilization. They have traveled through every mountain valley in Tibet and brought the care of the Party and the friendship of national unity to every ethnic minority compatriot. Our scientific and educational workers helped the Tibetan people to gain ideological liberation, promoted the improvement of productivity and the great progress of social development, and enabled Tibet to keep up with the times and move towards a modern tomorrow together with the whole country and the world.

“Since the 1970s, the state has invested huge sums of money, and the Chinese Academy of Sciences has organized a large team to conduct a large-scale scientific survey of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau for more than 20 years, covering various scientific fields such as geophysics, geography, geology, geomorphology, hydrology, meteorology, biology, and ecology. In the 1990s, the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau Scientific Expedition Team has grown more than a dozen academicians of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and the Chinese Academy of Engineering, trained batches of masters and doctors, and published more than 170 invaluable scientific monographs. The scientific expedition team also put forward many valuable scientific suggestions on the regional development of agriculture and animal husbandry in Tibet, the construction of geothermal power stations, the construction of nature reserves, and the development of other natural resources such as biological resources, which were adopted by the People’s Government of the Autonomous Region and the competent departments. The scientific research results of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau have a far-reaching impact on the international earth science community; they have made immeasurable contributions to the economic construction and social progress of the whole country and Tibet. How to express the feats, spirit and contributions of Chinese scientists in a popular language and form, show them to the world and educate future generations? How to save these extraordinary experiences and moving deeds while most of the old scientists who participated in the scientific expedition to the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau are still alive, leaving a valuable spiritual wealth for the scientific and technological community in China and even the world? We Tibetans who directly benefited from this should sing praises for these scientists and build monuments for them! Some even sacrificed their precious lives. In a certain unit stationed in Medog [Metok/Metok མེ་ཏོག་རྫོང་། / Motuo 墨脱] alone, 28 people died in peacetime to escort the scientific expedition team and people coming and going. Once an avalanche occurred at Duoxiong La Pass, and 5 soldiers all died heroically in order to protect the scientists, and the scientists were safe and sound. These heroic feats that shocked the world and moved the gods and ghosts should be written in the immortal history of the Republic and remembered in the hearts of people of all ethnic groups. How many touching stories, how many vivid examples of tenacious struggle, and how many heart-wrenching emotional waves can be found in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau scientific expedition team.

“The scientists of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau expedition team embody the combination of modern scientific spirit and traditional virtues of the Chinese nation. What they left us is not only a series of priceless scientific monographs, but more importantly, a spiritual wealth worth passing down from generation to generation. This spiritual wealth is invaluable in the history of Chinese science, the history of world science, the Chinese nation, and all mankind.”[5]

Yet this gushing praise song to Guan Zhihua and all the heroic Han who envisioned a massive hydrodam at Metok མེ་ཏོག་རྫོང་། / Motuo 墨脱, is does not contain any update on the dam’s prospects, even though the author was on the 1996 team “to conduct the first pre-preliminary investigation of the Big Bend Power Station.” By 1996, the more China explored the feasibility of its megadam vision, the more complicated and risky it became. Next blogpost plunges in further.

[1] Brian Yanity, Hydropower Development in the Tsangpo-Brahmaputra Basin: A Prime Prospect for China-India Cooperation, ISBN-10: 0989456307, ISBN-13: 978-0-9894563-0-2, downloadable from https://www.smashwords.com/books/view/328647

[2] Susan Greenhalgh, Missile Science, Population Science: The Origins of China’s One-Child Policy, The China Quarterly No. 182 (Jun., 2005), pp. 253-276

[3] 西藏河流水资源, 中国科学院自然资源综合考察委员会中国科学院自然资源综合考察委员会, 自然资源. Water Resources of Tibetan Rivers, Guan Zhihua, Chen Chuanyou, Committee for the Integrated Examination of Natural Resources of the Chinese Academy of Sciences Natural Resources Jnl 关志华,陈传友1980, (02) 25-35

[4] 1990 Scientific Atlas of Tibet, Science Press, 1990, 16

[5] https://igsnrr.cas.cn/sq70/hyhg/kxsy/201009/t20100917_2965409.html On this web page of the Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, Beijing , the only words in English are the Tibetans calling out ‘Yang Yichou”, indicating Yang Yichou has become a Tibetan word signifying all Chinese scientists.