This blog series reflects on where Tibet is headed, propelled to its’ destination, not only by China’s coercions but increasingly by China’s money and urban comforts. Reflecting back on the past 45 years, since communism, revolution and Cultural Revolution crashed, and ahead to the momentum China imposes. Those 45 years are also the years I have been engaged with Tibet, starting with a radio documentary series broadcast in 1979. So this is personal for me.

But if we want to discern broad trends spanning decades, inevitably we have to wrestle with China’s ideologies, its’ -isms. Xi Jinping’s China is highly ideological, which meant in the first blog getting to grips with governmentality; in this blog the developmentalist state, urbanisation, intensification, extractivism, rectification, assimilation, contiguous destitution, false consciousness, self-revolution 勇于自我革命. Apologies.

Gabriel Lafitte

BLOG 2 OF 4

THE NATION-BUILDING DEVELOPMENTALIST STATE

De velopmentalism is an ideology, a fixation on development and wealth creation as the solution to almost all problems. China did not invent developmentalism, but has taken it further than predecessors such as Japan, Korea and Taiwan.

China today sees endless growth as the core promise of the CCP, core legitimator of party rule. Xi Jinping’s China struggles now with achieving endless growth, but that has not changed the soteriology of growth as China’s utopian destiny, and its right, the right to become as wealthy as the richest of today’s nations.

This obsession with wealth creation aka development, sits ill with China’s claim to be global leader of green energy transition, hydropower, solar arrays on a massive scale, wind, lithium batteries, electric cars etc etc. China wants the world to see it as the champion of a clean, green, decarbonised planet, yet the ambition, nurtured by developmentalist, interventionist state subsidies and central planning, is at odds with a nature positive future that accepts limits to how much of the planet we can extract and consume.

Somehow this contradiction is seldom noticed, even though China, in Marxist tradition, is keen to identify contradictions. China, put simply, wants to have it all; to be at once both developed and developing, leader of the Global South and superpower. Forever intensifying production and consumption are intrinsic to China’s drive for “comprehensive national power” and “high quality development.” Tibet is designated specific roles in this national mission for greatness, explored below.

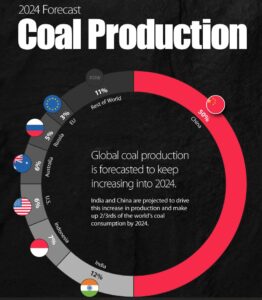

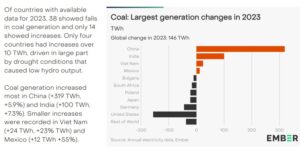

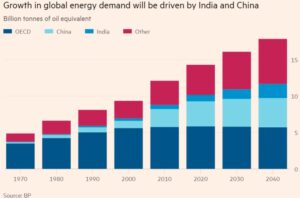

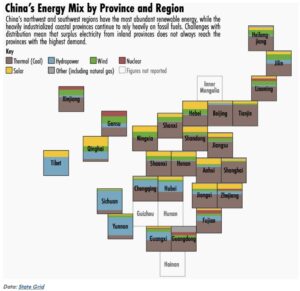

The crunch is evident in the energy statistics. The green economy is just as energy intensive as the old fossil fuel economy, if not more so, as major new industries such as big data crunching, crypto mining and electric car battery manufacture all gobble electricity, so much so that China keeps on building more and more coal fired power plants, to keep pace with demand, as well as lots of hydro dams and solar arrays.

The Five-Year Planners of China’s developmentalist state have a long track record of picking winners, and ensuring they do win, not only by subsidising promising national champion corporations, but also by compulsory corporate mergers, and massive infrastructure spends to ensure new enterprises move westwards, deep inland to new industrial sites, and have available all the electricity, roads, connectivity and compliant workforce they need. The developmentalist state provides the whole package that ensures the next national champions will succeed, and get big enough to venture abroad, doing deals with authoritarian governing elites worldwide. Developmentalism is a complete package of growth, capable of taking new industries, marketed as green, as the dragonheads of China’s expanding market power.

CHINA DEMANDS TO HAVE IT ALL

How does the developmentalist state define itself? Here, in the October 2024 words of a leading CCP ideologue and Xi Jinping loyalist Ke Ruiwen: “A deep understanding of the significance of building science and technology-based enterprises. In the construction of a strong science and technology country, enterprises are the main body of scientific and technological innovation, and are an important carrier for providing high-quality science and technology supply. General Secretary Xi Jinping pointed out that we should pay attention to the role of leading science and technology enterprises as the “questioner”, “answerer” and “marker”; central enterprises and other state-owned enterprises should be brave and dare to take the lead, and act as the “source” of original technology. The central enterprises and other state-owned enterprises should bear the heavy burden and dare to take the lead, and be the “source” of original technology and the “chain leader” of the modern industrial chain.

“Implement the spirit of the General Secretary’s important exposition, enterprises, especially the central enterprises, to build and strengthen the construction of science and technology leading enterprises as the goal, consciously fulfil the mission to promote a high level of scientific and technological self-reliance and self-improvement of the mission to bear.

“General Secretary Xi Jinping pointed out that we should focus on playing the role of tech-leading enterprises as “question setters,” “answer providers,” and “evaluators”; central enterprises and other state-owned enterprises should take on heavy responsibilities, dare to take the lead, and strive to be the “source” of original technology and the “chain leader” of modern industrial chains.“ This tech developmentalist rapture was published in the CCP theory journal Qiushi, October 2024. Much more online.

Does this read like a country leading us all into a clean, green future? Or an industrial giant determined to get bigger?

IDEOLOGY RULES

Both governmentality and developmentalism are powerful and comprehensive, since both present themselves as diagnosis and cure, problem and solution, contradiction and resolution. They become dominant discourses through their ability to define cause and effect. So we need to interrogate China’s solutions to undefined problems. If developmentalism and governmentality are the answers, then what is the question?

Once in place, these discourses become normalised, their assumptions unquestioned, self-evident, common sense. China tends to talk of “laws of development”, as if they exist objectively. Beyond China, no-one has heard of these “laws of development” beyond basics of production.

Economics orthodoxy defines the “factors of production” as land, labour and capital. That disadvantages Tibet and the Tibetans, because only certain lands are endowed with the right location to attract capital, and land is immobile, while capital is mobile, can flow to wherever the land connects easily to transport corridors, urban markets, energy supply. Tibetan landscapes are, by comparison, remote, population scattered, little coal and oil, cold and hypoxic. So labour, like capital, must flow to where the other factors of production naturally gather. Tibetans must emigrate, if they are to become modern, civilised, productive.

Now China has further tilted these “laws of development” even further against Tibetans, by inventing new factors of production, a new top layer, a new higher rung on the ladder Tibetans are expected to climb. Now labour is no longer a single factor of production, now we have the New Quality Productive Forces, as a new elite category, a concept now so frequent it is usually just NQPF.

The platform economy, big data wrangling, AI, high tech are all New Quality Productive Forces, who enable China to grow and grow forever, largely by inventing new human desires, which influencers turn into wants, and then into needs, to be consumed.

“NQPFs today refer in particular to the technologies of digitalization, networking, and intelligence, which have spawned a new era of scientific and technological innovation, new industries and economic models, and social development. New business forms and models continue to emerge, and the transformation of traditional industries continues to advance. The resulting impact is reflected not only in the fields of natural sciences, economic development, and productivity but also has a revolutionary impact on the machinations of human society, production organization methods, social organization operations, and social system.”[1]

POLAR OPPOSITES: NEW QUALITY PRODUCTIVE FORCES vs CONTIGUOUS DESTITUTION

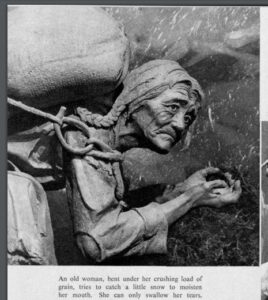

The party-state’s elitist insertion of a new factor of production makes Tibet more of a peripheral loser than ever, condemned by its nature to “contiguous destitution” 个集中连片特困区贫困 gè jízhōng lián piàn tèkùn qū pínkùn , a damning designation that pictures Tibet as inherently and incurably poor, because of its comprehensive lack of factor endowments, not just in one district, but contiguously across huge areas.

In this party-state gaze Tibet lacks all three factors of production: land, labour and capital. The lands of Tibet are in Chinese eyes unnaturally frigid, and the air too thin. Labour lacks the most essential qualification, which is fluency in standard putonghua Chinese, and even more lacking in high quality skills for building the future development path. Tibet lacks capital because rural Tibet has long been under-capitalised, neglected, depicted as unproductive, because China never invested in adding value to Tibet’s comparative advantages, its capability of producing to excess the many products of livestock rearing.

Since Tibet lacks all three factor endowments, it is inevitably poor, remote, backward, uncivilised; in short contiguous destitution. A simpler way to say this is that, given a choice, no-one would choose to live in Tibet. That is the implicit assumption of China’s gaze.

Harnessing these New Quality Productive Forces requires orchestration by skilled orchestra conductor, with a vision of the end result. This means picking winners, nurturing national champions, favouring the rich, or even better the party-state itself becoming entrepreneurial as well as regulatory and stimulatory.

PICKING WINNERS

The genius of the developmentalist state is spotting and backing trends. Business schools worldwide analyse corporations seeking a slice of the market as early entrants or late movers. If you are a late mover, you will find it tough to create a niche for your product in the market, because the long established brands have the game sewn up, from raw material sourcing to production lines to consumer brand loyalty. So, the reasoning went, China was a late mover in car and truck manufacturing, having to compete with the famous brands of Germans, Americans, Japanese and Koreans, tough.

But China turned this logic on its head, making late entry into early mover advantage, by switching to lithium battery electric cars. Developmentalist China reinvented the car, not just the engine. Cars became rolling entertainment systems, providing every format of consumer gratification found in your home, now on wheels. The car still gets you from A to B, but on the way you have instant access to everything from gaming to karaoke to porn to news, separately for each seat. In the not far off future not only passengers but also the driver will be enveloped in their own personalised private world of entertainment, since the cars will be self-driving.

The big brands didn’t see this coming. Now Volkswagen, Audi, Ford and the other names known worldwide are facing existential crises. Only a developmentalist state can do this, as long as it also has secure supply of raw materials.

DEVELOPMENTAL EXPERIMENTAL

The developmental state needs spaces where it can experiment with new technologies, access secure supply of raw materials, run trial projects, scale up to mass production, install new tech on an impressive scale, making those new spaces a laboratory-cum-showroom for installations sold worldwide.

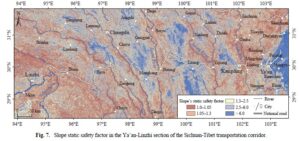

The biggest such space is the Tibetan Plateau, a geography the size of Western Europe, ideal for developmentalism to build entire value chains, from raw materials mining to sales room demonstration base for visiting delegations.

TOP-LEVEL DESIGNING THE FUTURE

Just as governmentality is much more than what governments do, developmentalism is much more than the sum total of development projects. It is an ideology that privileges “development” as the core justification of state power, legitimating state interventions that shuffle people and populations around, in the name of realigning the poor and backward with the factor endowments obtaining in different landscapes, removing people from lands classified as “contiguous destitution”, where poverty is deemed unending and incurable, to landscapes where factors of production cluster in enclaves suited to modernity and intensive industrialisation.

Governmentality, sovereignty and developmentalism in China closely align. Governmentality is the underlying agenda,, disciplining all citizens to obey the ever-present state, by absorbing and accepting the state’s civilising mission, even when citizens are suddenly scythed like jiucai chives, for reasons of state.

Sovereignty insists China is a unitary nation-state in the international system. That means other sovereign states must accept refraining from raising human rights, since that is “interfering in China’s internal affairs”. Sovereignty also demands respecting China’s unique status in the international system as a developing country and leader of the Global South, exempt from any requirement to finance climate mitigation across the Global South, despite being the world’s biggest emitter.

WALKING BOTH SIDES OF THE CLIMATE STREET

In the 2024 global climate COP on climate finance in Azerbaijan, we saw the disastrous consequences of China’s unique status in the international system, as a developing country that happens to be the world’s biggest emitter of climate heating gases. Back in 1992, when the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was agreed, China was classified as developing, not one of the rich club, thus exempt from obligatory contributions to finance protection for the poorest countries which did least to cause the climate crisis.

The Azerbaijan COP29 is widely seen as having failed to step up financing to anywhere close to what is needed. A major reason the richest countries drag their feet is that China is not required to be part of the financing deal, and any (modest) amounts China provides to the Global South are not part of UNFCCC; they are China’s bilateral benevolence to client states, and details are usually secret. China has gotten away with this double standard for decades. Very few notice how China manages to walk both sides of the street.

How come China gets away with this double standard, and is not called out for it? No-one wants to say this aloud. Global South countries, reliant on China’s investment, don’t want to annoy China, their patron, for no benefit to them. Environmentalists and climate activists cling to the hope that China is a good actor, doing the right green energy stuff in a Trump world. The rich countries reluctant to invest enough finance needed by Global South know that if they blamed China for their reluctance to do the right thing, they would be howled down. So no-one says anything, and China gets away with it; unless Tibetans speak up on loss and damage to Tibet directly attributable to China’s accelerating industrialisation ambitions.

CHINA LEARNS FROM ITS NEIGHBOURS

Developmentalism, as an ideology of industrialisation, urbanisation, intensification and acceleration, has been widely applied to Japan, Korea and Taiwan, to explain what drove their rapid growth in the second half of last century. Developmentalism is a way of thinking that encompasses China’s statist, nation-building, state building, infrastructure-led boom period from the late 1980s to the present.

Governmentality and developmentalism are similar. Both identify top-down state power that disciplines, mobilises, relocates masses of people because “laws of development” necessitate their removal and relocation. Both ideologies disempower those whole regions and lands deemed backward, uncivilised, poor, lacking in factor endowments. Both are about much more than the fetishised metric of GDP as the sole measure of state success. Both are civilising missions, with explicit agendas that instruct the relocated in how to dress, how to walk in public, not spit, wash hands, learn hygiene, obey instructions.

DISDAINING THE UNCIVILISED POOR

Among the educated urban elite in China it is just obvious that the poor are backward, deficient in human capital formation, uncompetitive, lacking quality; thus in need of guidance by a strong state with will and capacity to discipline and direct the backward into history, development, modernity, civilisation, urbanisation and competitiveness. A typical example of elite contempt: “They are also trapped in a perpetual present, obedient and submissive to their biological drive.” [2] The strong state depicts itself as bastion of rationality and objectivity, bolstered by its “top-level design” of policies, its mastery of all technologies of governmentality. The poor, and the uncivilised ethnic minorities of the border regions remain trapped in their timeless, ahistoric eternal present, in their animal desire for immediate gratification. So the state, both wise and strong, has every reason, and ability, to rescue the poor and uncivilised from the false consciousness that prevents progress, scything them like jiucai garlic chives, so they can now regrow in a better way. Treating the masses with contempt. This is deeply racist, so ingrained no-one in China talks about it.

In the official gaze, if the state decides people must be removed and relocated, if entire geographies must be depopulated, it is because the state possesses superior reasoning, including a strong capacity to predictively foresee the future, based on a massive gathering of data points on what has happened in the past. If the relocated are unhappy, that is merely symptomatic of false consciousness. Put simply, they don’t know what is best for themselves, but the state does.

The party-state insists it knows best. This echoes emperor worship in dynastic China. That collapsed 150 years ago, now resurrected as mandatory worship of an all-knowing ruling party. That now fills the vacuum, after 150 years of repudiating tradition. Today’s China resurrects the state, no longer mandated by heaven, now mandated by definition by the masses in whose name the revolution was won.

The People’s Republic is ruled by the people because the Chinese Communist Party embodies the will of the people, even when the people don’t know what is good for them, which necessitates yet another mass campaign to mobilise the masses to assent to being rectified. In Marxism this is called false consciousness. Circular logic.

In order to restore the worship of the state, much as dynastic China required everyone to worship the emperor, the state must first know the people, must gather torrents of data about the masses and each individual. All citizens must become legible, scrutable, visible, available to the interrogating eye of mass surveillance, so the minds of people can where necessary be rectified. The ruling party is now officially everyone’s family surname. Xi Jinping declared in 2016 “Media run by the party and the government is a propaganda base and must follow the surname [display complete loyalty] of the party.”

Circularity is complete. The CCP embodies the will of the masses because its’ media monopoly educates and disciplines the masses to internalise the party-state’s power as natural and inevitable.

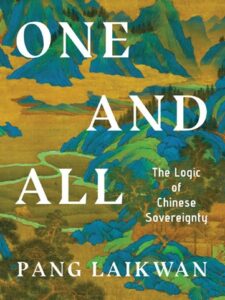

Pang Laikwan, at Chinese University of Hong Kong: “What really characterizes the current “Chinese path,” I believe, is the enormous weight given to the security of state sovereignty, which is the bottom line of all policies. State security in the PRC encompasses many fields, and the list keeps expanding, from cultural security to cyber security, and more recently finance security and food security. Under this general security anxiety, society is monitored by intense censorship and self-censorship in the name of protecting the collective from all kinds of threats, real or imagined.

WHATEVER IT TAKES

“I would use the term “sovereigntism” to describe how this state uses sovereignty as its supreme political doctrine. This utilitarian sovereigntism employs contrasting logic, from autocracy to neoliberalism, selectively to support its internal and external policies, in ways that can potentially advance socialism, capitalism, nationalism, and globalization as long as they are deemed beneficial to the sovereignty. In the name of the well-being of the people in general, sovereigntism allows the state to adopt almost any measures, regardless of the underlying ideologies, to secure its sovereign interests.

“It is the arbitrary and empty quality of sovereigntism that makes individuals so afraid and obedient. Instead of valuing debates and negotiations based on the principles of equality and plurality, sovereignty is often exercised through command and obedience. All state decisions can be legitimized as long as they are made in the name of the people. But there are never any systematized and continual procedures to prove the people’s endorsement and choices.

“Sovereigntism provides an illusion of unity and certainty for the people. This integrity of state sovereignty is understood as a trio: the coherence of and among people, territory, and history to the extent that each accounts for the others. For example, the Xi government points out that there is one Chinese dream that all Chinese share, which is the dream of restoring the national greatness lost in recent history. Indeed, the Chinese dream is presented more as a bygone fact than a future vision, that China is always already a unity of people and territory historically. This one people that shares the same country and history deserves the strength and pride that originally belonged to it.

SECURITISING SOVEREIGNTY

“Modern sovereignty is not only an economic-political ensemble, but most importantly it is also a culture. More precisely, sovereignty is a state-people-territory-history imagination. State sovereignty is both an institution and a political persuasion, involving many levels of operations and discursive practices. It is also a political theology, conveyed through apparatus of law, education, and propaganda. Before it is an institution, sovereignty is a culture, a general set of ideas, beliefs, and identification that permeates a community. From a cultural perspective, we can conceptualize modern sovereignty as primarily a space where lineage and authority are established and challenged and where the mutual identification between the state and the people is operated in a field of open-ended language and representation.

“I pay particular attention to intellectual culture because sovereignty is primarily a claim, or an imagination, negotiated between the state and the people. The state cultivates the people’s identification with its sovereign power, but the people also benefit from the sovereign power to develop their own ambitions. It also embodies the people’s desire for stability and solidarity. Nationalism alone cannot encompass and explain such a complex dynamic, particularly considering that individuals act and position themselves for both strategical and emotional reasons.

“Discussions of state sovereignty often also hinge on a dual structure: externally against foreign interference and internally against domestic disorder. Indeed, our imagination of sovereignty tends to be based on a coherent and confident individual, capable of managing and controlling one’s own self.

“But because the state is composed of many individuals, the state as the representation of the people implies a power transaction, in the sense that the modern state operates through citizens’ voluntary transference of their authority to the state. Collecting the power of the citizens, the state could become coercive due to, and despite, these originating forces. It is often difficult to differentiate “the sovereignty belongs to me” from “I belong to the sovereignty.”

“China’s current sovereign logic displays a strong animosity toward liberalism, where state economy and collective good matter more than personal liberty. Its rapid economic development in the last three decades, as interpreted by many critics, proves the effectiveness of this sovereign logic. But the Chinese state has clearly exploited the people’s willingness to negotiate personal liberty: the grave consequences of the state’s enormous power in intruding into their private life has been painfully felt by citizens in the COVID-19 lockdowns. The ruling regimes might be changing rapidly, but they all have to manipulate the myth of unity and to appropriate China’s internal plurality and changes in international relations to empower the state’s sovereignty. The ruling regimes both revere and fear revolution.

A REVOLUTIONARY PARTY FEARFUL OF REVOLUTION

“Both the Republic of China (ROC Taiwan) and the PRC obtained their sovereignty through revolutions, and the ruling regimes have incessantly returned to their revolutionary victory as their source of legitimacy. But the sovereign powers also fear revolutions the most, trying to repress seeds of dissent at all costs. Demonstrating how revolution was central to both the KMT and the CCP sovereign power challenges our assumption that sovereignty is an entity of stability and permanence. It also shows how violence is central to state sovereignty.”

China’s sovereign state insists it is unitary, one people within one territorially defined boundary, with all separate national identities trivialised as arbitrary personal choices of individuals, with no presence in the public sphere.

Today’s sovereign state is not the first in China to insist that a single racial origin, a single source of identity applies to all citizens of China. A similar assertion manifested in the Manchu Qing dynasty. Since the Manchu Qing ruled China as conquerors sweeping in from the steppes of the north, this required adroit juggling enabling them to somehow be both alien and Confucian.

Pang: “a new shift in statecraft from cultivating the people’s personal morals, which had been central to the dominant Confucian teaching developed since the Song dynasty, to an emphasis on imperial unification. These Gongyang scholars tried to follow the government of the Han dynasty that played down racial differences and emphasized the smooth operation of a grand unified empire while also strictly following the teaching of the Confucian classics.”

ERASURE

Under Xi Jinping this insistence on unity, and erasure of difference, now dominates. Everyone is commanded to live like seeds in a pomegranate, packed close together, in compulsory harmony.

Pang Laikwan 54: “There is a core contradiction that defines sovereignty: to maintain the group’s autonomy, we must sacrifice the members’ autonomy. Unity is the linchpin of this structure, with the assumption, supported by some historical experiences, that only a unified people is strong enough to defend itself from others. Governments tend to construct the unity of the state as a myth to hide the stratification of its process and practices.”

Pang Laikwan76: “Overall, Socialist China was a much more powerful sovereign state than its immediate predecessor, and it was also able to pull together a huge territory more or less according to the Qing map. But its sovereign unity was achieved at a high price. It was caught up in the polarizing Cold War structure in which state sovereignty was compromised, and the central government also time and again suppressed the cultural identities of ethnic groups instead of helping them flourish, causing deep wounds. China’s sovereign structure could have been a radically different one if the Maoist ideology had been able to develop into some fruition, where international collaboration was not based on sovereign interests but common political values, where respect for racial differences reconciled with the socialist ideal of equality. Although the actual term “sovereignty” was seldom mentioned in the socialist period, its logic permeated and muddled China’s politics in profound ways.”

CIRCULARITY AND SELF-REVOLUTION

Governmentality differs from developmentalism, beyond the overlap. Governmentality requires the citizen to not only accept being disciplined by the state, but to internalise and identify with the discipline, conforming to the identity the state requires. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XvWsIR5_bOs

This is the self-revolution Xi Jinping repeatedly calls for, which requires much more than begrudging outward compliance. What the party-state demands is inner surrender.

Zhao Lejii knows a lot about self-revolution. Well before he became CCP secretary in Amdo/Qinghai, he was born into a revolutionary pioneer family who migrated to frontier Qinghai to civilise the Tibetans. Exemplary heroes of self-revolution. Zhao Leji: “General Secretary Xi Jinping emphasized that the courage to self-revolution is a distinctive feature of our party that distinguishes it from other political parties, and is also the key to the party’s long-term prosperity; to forge iron, one must be strong, and to uphold and develop socialism with Chinese characteristics, our party must have the courage to carry out self-revolution; the spirit of self-revolution is a strong support for the party’s ability to govern, and we must adhere to the unity of upholding the truth and innovation, strengthen and improve ourselves with the spirit of reform and innovation, and constantly open up the future through reform and innovation; comprehensive and strict governance of the party is an inherent requirement of self-revolution, and we must always maintain the consciousness of facing problems and the courage to turn the knife inward, and take anti-corruption as a major political task that the party must grasp for a long time in its self-revolution. General Secretary Xi Jinping’s strategic thinking on leading the great social revolution with a great self-revolution inherits and develops Marxist theory of party building.”

Han Xiao, a professor of education in Tianjin: “This is the situation, that disciplinary system not only divides the individual from others but also operates internally within himself. The ‘process objectivizes him’ makes individuals internalize discourses and practices guiding their self-management. Such ‘disciplined self-management’ is achieved by applying the ‘anatomo-politics’, the disciplinary power, rather than merely ‘imposing laws on men’. With variation in sovereign ends, the (neo)liberal and illiberal nations similarly wield disciplinary power to establish the ‘desirable and the undesirable’ goals, toward which the individuals subjugate themselves as out of free will.”[3]

IS CHINA CAPITALIST OR COMMUNIST: DOES IT MATTER?

China watchers worldwide debate endlessly whether under Xi Jinping China is reverting to state ownership and the socialist ideology of the Maoist era; or whether China’s massive stimulus of a chronically sluggish economy is a restoration of private enterprise. Investment advisers anxiously seek clarity: in which direction is China turning? For investors and US legislators that may be the key question, yet it ignores a more basic question: is the CCP regime fixated on governmentality, and will adopt market economics, or statist developmentalism, whatever suits the regime at the time, with no abiding ideological commitment to either?

Governmentality means China embraces both and neither, depending on CCP assessments of whatever maintains party-state power at any time.

Hence the paradox of governmentality in illiberal, authoritarian China: the state wants you, as a consumer, to be an individual, with tastes, values, consumption preferences; yet demands you, as a loyal citizen, internalise state ideology and behave in conformity.

A further major difference between developmentalism and governmentality is that governmentality explicitly understands state building as the core purpose, including the inscription of sovereign nation-state power into all landscapes and populations. Developmentalism recognises such drivers, but is more focussed on economic outcomes, and economic reasons why developmentalism runs its course, why GDP growth slows or stagnates, why statist orchestration may eventually fail.

Where the concept of the developmentalist state diverges most from state governmentality is basic: developmentalism is an ideology, governmentality embraces and then drops any ideology, according to its singular purpose of maintaining the dominance of the state.

What worries the embedded ruling party is that the promise of prosperity is the core promise of state legitimacy for the past 40 years, a promise now worn thin. All over China, as economic growth slows, people see Deng Xiaoping’s invitation to get gloriously rich as hollow. They see an urban elite clustered in tier one cities who capture the generation of wealth, amid vacuous slogans of “common prosperity” delivering little by way of the core promise of socialism, which is state redistribution of wealth. China’s spending on health, social welfare and education remains low, with local governments bearing most of the costs; while at nation-state level the CCP is now a party of red princelings and millionaires whose disdain for the “low quality” masses is palpable.

CONSUMING TIBET

Is any of this relevant to Tibetans? China’s top down ideology of disciplining the masses to conform applies forcefully to Tibet, but extends far beyond, becoming a rectification campaign that all citizens of China must comply with.

Yet the pushiness of party-state ideology, combined with ruthless urban competitiveness and relentless corporate 996 work culture, have exhausted many in China who now choose to drop out and lie flat. That refusal to obsessively compete worries party leaders, who urge everyone to stay in the race to China’s comprehensive national power.

This too impacts Tibet. Where better to drop out than in Tibet? Lhasa has long attracted Han dropouts, as a place to hang out.[4] A recent trend is “nursing homes for young people”, where Han new gens can drop out, enjoy old fashioned pleasures, and leave behind the urban rat race. “Life in the city is so fast-paced I feel like I can’t take a breath,” said a 27-year-old woman from Beijing who was staying at the lodging.. “Staying here, I feel like I’ve come back to my childhood home,” a man in his 20s said with a smile. The guesthouse, which opened in July, is one of a growing number of so-called “youth nursing homes” that are popping up across the country. These places offer a space where guests — most born in the 1990s or later — can relax like senior citizens may do after retiring.” No need to go as far as Lhasa, plenty of funky guesthouses in Tibetan Yunnan. If only one percent of Han drop out, that is 12 million emigrants.

Similarly, quaintly ethnic towns just below Tibet have long been overrun by mass Han tourism, seeking a break, slowing down, a relaxed pace, courtesy of their laid back ethnic hosts. At the foot of the plateau, Lijiang and Dali have been transformed, as Alec Ash tells us: “Already the town of Lijiang to the north had touristified, rebuilt after an earthquake in 1996. It took Dali’s government longer to catch up to the commercial prospects of its natural beauty, but in the mid-2010s the Old Town was renovated, rents were hiked, souvenir shops set up stall, and the hippies moved out to surrounding villages. Dali was back on the map. It became a trendy escape from the hubbub of the cities, for both tourists seeking a temporary break and reverse migrants looking to reinvent themselves.

“In 2014, Chinese folk singer Hao Yun penned a hit song that captured the zeitgeist: ‘Go to Dali’. ‘Are you unhappy in life?’ went the lyrics. ‘Haven’t laughed for a long time and don’t know why? Go to Dali! Go to Dali! If you’re not happy and you don’t like it here, why not head west, all the way to Dali?’

“These city arrivals in the countryside were dubbed fanxiang qingnian, or ‘returning youth’, although every generation was represented. Some called themselves xinyimin — the ‘new migrants’. Others used a simpler term: new Dali people’.’[5]

The response of the developmentalist state to Lijiang and Dali overrun with tourists, squeezing the locals out as rents shot up, was to invest RMB 22 billions in building a tollway and railway from Lijiang up to Dechen in Kham, the new frontier of Han mass tourism. Onwards and upwards. A triumph of blasting tunnels through the mountains, to build the Lixiang rail line, its name a conflation of Lijiang and Xiangerlila (Shangri-la)/Dechen. Now Dechen is just 90 minutes from Lijiang by car or rail.

The developmentalist state collapses distance and accelerates time. Tibetans in Dechen experience this in daily life, yet there is much more coming, as developmentalism further warps time and space. This blog is focussed on long term trends as well is in-your-face impacts.

Since censorship makes it almost impossible within China to articulate this disillusion, many are simply dropping out of the competitive race for wealth and power, the race dominated by insider networks, gifts, favours and banqueting deal-making. Governmentality demands women have more children, everyone works hard, everyone worships the state, so these trends deeply worry governmentality. Whatever is needful must be done, irrespective of its ideological tags.

The similarities between these mentalities are sufficient enough for us to look more closely at what actually happens in the lives of people who, in the name of development, modernity, civilisation, have been displaced, sent to new zones of development. We are able to judge outcomes of developmentalism on its own terms, on its claim to generate income in communities of the relocated. See the next blog in this series.

The developmentalist state, we can conclude, is inherently colonialist, armed with preconceptions as to what remote “underdeveloped” communities need. China never asked Tibetans what they need, the CCP knew best. China adopted, without critique, a Western post-WWII concept that neatly divides the world into “developed” and “underdeveloped.” This has imposed universalism on the reality of pluriverse 多元世界.

This blog has not grappled with the many critiques of development, developmentalism and the developmentalist state that are readily accessible, but does recommend them.

[1] Understanding new quality productive forces, https://www.china-briefing.com/news/chinas-new-quality-productive-forces-an-explainer/

[2] Pang Laikwan, “China’s Post-Socialist Governmentality and the Garlic Chives Meme: Economic Sovereignty and Biopolitical Subjects,” Theory, Culture & Society 39, no. 1 (2022): 94

[3] Xiao Han, Tianjin University, Disciplinary Power Matters: Rethinking Governmentality and Policy Enactment Studies in China, Journal of Education Policy, Volume 38, 2023 – Issue 3 : https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2021.2014570

[4] Junxi Qian & Hong Zhu, Han Chinese “drifters” in Lhasa: the ambivalent cultural politics of Tibetanness amidst China’s geographies of modernity, Social & Cultural Geography, 17:7, 892-912, DOI: 10.1080/14649365.2016.1139170

[5] Alec Ash, The Mountains are High: a year of escape and discovery in rural China, Scribe, 2024