blog two of four on movies filmed in Tibet #gabriellafitte

For a while, Gang Rinpoche/Paths of the Soul was a surprise hit with Chinese audiences, doing better than Hollywood megamovie Transformers, released at the same time. Media speculated why.

ANATOMY OF A FAILURE: GANG RINPOCHE RISES WITHOUT A TRACE

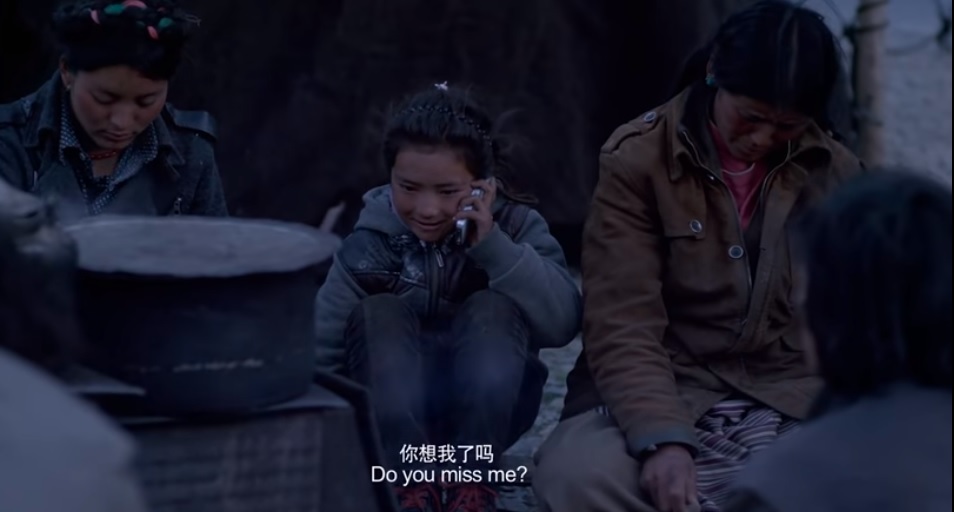

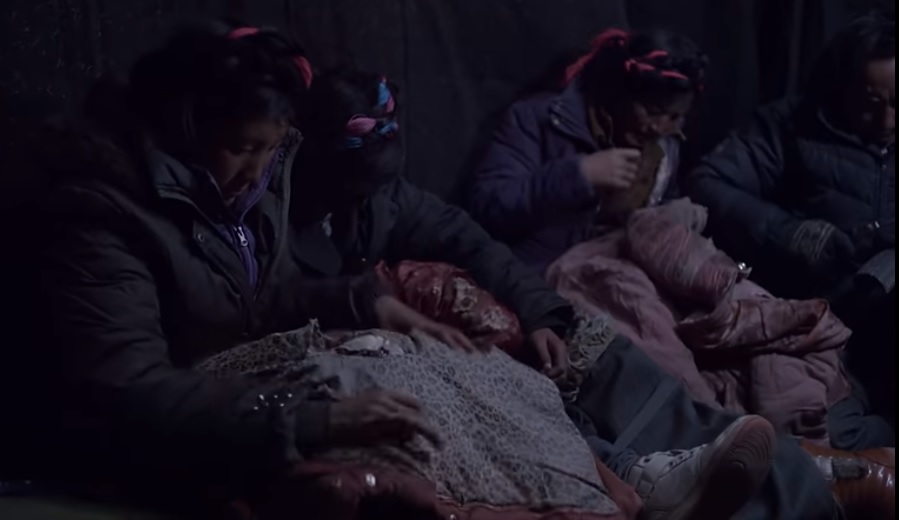

Throughout Gang Ripoche the director refrains from deploying basic story telling film techniques that are embedded in media-saturated audiences, as film analyst Chris Berry reminds us: “In the interior scenes, the camera often pans or tracks laterally across the people in the room as they talk. Point-of-view and shot-and-reverse shot structures are avoided. Not only does this discourage identification with any individual character on the part of the audience, but also it gives a sense of almost ethnographic observation and distance of the pilgrims as a mass, because they all share the same values and culture.”[1]

This seems to be the problem. We are primed to select which individual we identify with, and who we dislike. While each pilgrim has specific personal reasons for going on nékor, once they are on the road they become a collective noun, the nation incarnate. Zhang Yang seldom pushed his cast to do take after take, necessary to the shot-and-reverse grammar of film that enables the viewer to see in close up the range of emotions as characters wrestle with what to do next.

Is this a failing? If we just don’t care, don’t engage with individuals we can identify with, we aren’t going to care much about the group; they are just too agreeable. This makes it, Berry suggests, more like an ethnographic film of types, rather like the minority ethnicity albums of past centuries, in which Han painters focussed on typically different behaviours, as seen through Han norms.[2] Typology is for museum dioramas, not the box office.

Director Zhang Yang insists the lack of drama is simply because, to Tibetans, taking months or even a year or two to do a pilgrimage is not heroic, or even exceptional, it’s ordinary, even natural. The cast we meet is not exceptional. Not only are they not heroic, they are not especially sinful either, and thus on a path of redemption. For a butcher to awaken to the harm he has done by animal slaughter is the same natural awakening we all experience, and which, in Tibetan opera, is a pivot in the drama, yet always happens offstage, because awakening is ordinary and inevitable.

Zhang Yang says: “For the Tibetan Buddhist, to make this pilgrimage at least once in your lifetime is a must, so it’s natural that they do it. What’s difficult was not to motivate the cast to do the pilgrimage but to explain to them what shooting a movie was and persuade them to participate. So I took a lot of time explaining how shooting the film would be. After the process, shooting the movie was not that difficult. What was difficult, in the beginning, was to find the right village, where all the actors I wanted in the movie were together. I was very lucky to find the village. For real Tibetan Buddhists it’s very natural that during the one or even two-year duration of the pilgrimages that a pregnant woman would give birth to a baby while she was on the road,” he says. “That’s what I had encountered before and why when I shot the film, I tried to find a village with such an actor – a pregnant woman – so I could include this scene in the movie. Very luckily, I found one. In the beginning, as I told her that on the road we would wait for the moment she gave birth and would capture it on camera.”

Maybe we recoil from Paths of the Soul/Gang Rinpoche because this ordinary readiness to undertake a year of full-on 24/7 practice for the welfare of all sentient beings, is too confronting. We all, Tibetans and nonTibetans alike, live busy modern lives, trying to stay in control and solve problems, beset by anxieties and risks. That others can so readily handle all risks, all challenges so calmly, and keep on prostrating, is just too much.

So the easiest response is to distance ourselves, to accuse these Tibetans filmed in 2015 of living in the past, or in a timeless ethnographic present, outside of history. That makes them artefacts, relics of a lost past, when Tibet was timeless, before modernity irrupted and accelerated everything.

Yet what if Gyalwa Karmapa is right, that we have become so busy, we are unable to understand emptiness, and thus unable to relate to others, perhaps only to one or two people whom we are able to love, keeping others distant? “We can’t understand other sentient beings because we are trapped in the same wrong views they are trapped in. It’s as if we are in a prison of our own making. You actually made the prison all by yourself. You made the prison; you are the prisoner, and you are the one who keeps the prison under lock.”

HEROIC CONQUEST

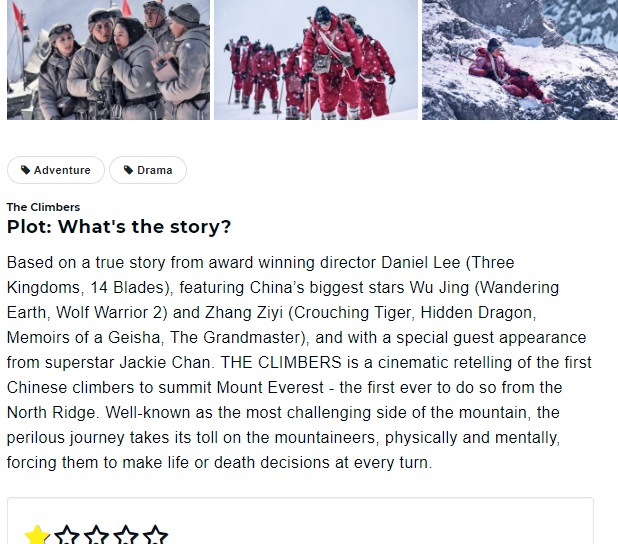

So let’s try a different angle, with a different film, also set in Tibet, which makes all the right camera moves. A very different movie single filing through the snow, released to coincide with the 2019 70th birthday of the People’s Republic, makes clear why some movies work and some, like Gang Rinpoche, fail. The Climbers is a 2019 hit, an epic set in 1960, of the first Chinese ascent of Chomolangma, Mount Everest. The Climbers, at a breathless pace,recapitulates China’s 1960 conquest of a Tibetan mountain, only seven years after Sherpa Tenzing Norgay and a New Zealander were first to the top. Two Tibetan actors have minor roles, Choenyi Tsering, and Tobgyal. The poster for the film proclaims: “For the country to climb the top, not to let the soil go.”

Reviewers beyond China found it a bit too full on: “a mode of storytelling that is 80% score-driven. Thunderous trumpets announce every step Fang makes in the right direction; keening strings signal lovey-dovey business. You should be able to cling to the traces of a sports-movie arc discernible beneath the layers of bombast.” It’s not only Chinese audiences who respond emotionally to trumpets and strings, swooping drone shots and CGI generated thrills. After all, Chinese movie makers learned this from Hollywood. Ticket sales on the first day of release were RMB 164 million, and film studio share prices rose. Then it faded fast. By trying too hard, too obviously to be both a romance and a wolf warrior badge of patriotism, The Climbers failed to revive interest in a forgotten triumph of 60 years ago.

Pema Tseden says he seldom swoops into close-up for the money shot because he respects his audience, gives them space to decide for themselves what to make of a scene; but we have become used to having our emotions manipulated by experts, our adrenaline surges on cue.

We have also sped up. Tibetanist scholar Roberto Vitali, responding to Pema Tseden’s films notes: “I have heard complaints that the movie is slow. Those, who say so, have probably not experienced the way time flows on the Tibetan plateau, away from the towns transformed into Chinese steel and mirror monsters. Time seems to be immemorial on the sandy plains and the hills lit by the sun. Life flows with a rhythm that has its own pace and everyone ― men, animals, even fierce winds ― seem to be aware of that.”

1960 is remembered in Tibet and throughout China as the worst of three years of famine, not for this mountaineering triumph, because all the film shot then fell off the mountain and was forever lost. A great leap to top a Tibetan mountain, was all part of the 1960 Great Leap to beat the West in steel production, at a cost of 30 million or more starving to death.

The Climbers does not ignore the famine , instead brazenly making it a further reason for patriotism. Even in the official trailer, one doubter asks: “Can climbing a mountain feed a few hundred million hungry people?” The decisive answer: “If a few hundred million people can only worry about what’s for dinner, what hope do we have for our nation?” This gratuitous insult to the grandparents of today’s ticket queue, those who did survive Mao’s great famine, is for today’s generation: patriotism is more important than eating.

KHAM TO THE HOLY CITY ONE PROSTRATION AT A TIME

A more obvious comparison with Gang Rinpoche/Paths of the Soul is a 2008 doco that is not only focussed on Tibetan nékor pilgrims prostrating all the way to Lhasa, it also starts in Kham. Even more obscure than Gang Rinpoche, this one hour Korean doco joins a group of Khampa men prostrating through all weathers and all landscapes, even up and down steep, stony slopes, way off-road, slip-sliding on the ice. More remarkably still, it too starts in winter and ends seven months and 2100 kilometres later in Lhasa, covering the same route and same seasonal cycle as Zhang Yang’s lens nearly a decade later.

Asian Corridor in Heavenis a six-part series made by Korean Broadcasting System, in collaboration with Japan’s NHK, Taiwan’s GTV, TRT and BBTV

Episode two, Road to Pilgrimage, and all six eps follow conventions of the doco genre, including a voice over narrator, overlaid music, hand held camera, lots of close ups and mid shots, occasional long shots. Only at the very end do key characters speak direct to camera, about why they do it.

The viewer is with this party of five, Busa, Lulu, Dawa, Choeji (Chogyal?) and Lappa (Lhagpa?), who have not even a tractor to pull a trailer of gear. They have only two light handcarts, each pulled by one of the five men, sometimes up slopes so steep they have to constantly weave across both traffic lanes, to lessen the gradient. In some places the road, designed by China in the 1950s for underpowered truck engines unable to manage steep gradients, so the road to or from a pass is endless switchbacks. There the men head off road, straight down or up hill, boulders, snow, ice and rubble notwithstanding, prostrating as best they can, without a break.

It’s riveting viewing. For starters, there’s no doubt as to whether it is staged for the camera, or scripted, it is palpably real. There’s nothing programmatic about it. The nuts and bolts of how to survive months on the road, in gales, blizzards, ice and snow gradually reveal themselves, the same basic technologies of survival as in Gang Rinpoche, including inventive roadside bricoleur stitching of leather aprons about to fall apart.

The viewer has time to see it all, the voice over is minimal, the music never too insistent. Lots of close-ups, you can choose who to identify with. Although it is an ethnographic doco, one of six filmed in Tibet, it is emotionally engaging. It all works, in ways Gang Rinpoche doesn’t.

By the time we are almost done, we are really keen to find out why would anyone do this, and we are ready for the matter of fact answers, from Lhagpa, a young Khampa who has awakened after alcoholic years, and now, having purified mind and body, intends a full time religious vocation. His body/mind prostrating prayers, he tells us, have been to become a different person, and there is little reason to doubt he has done it. His voice is not one of yearning, nor of 12-step AA self-recrimination. He is matter of fact: you can decide to become a different person, you can then actually become a different person, and my culture has specific methods to achieve this, and they do work.

The older man, Busa, is calmly facing mortality and the next life, saying that, at 66, “I want to someone with a big heart in my next life, so that I can lessen the sufferings of others.” This is the classic bodhisattva path. After seven months on the road, you can believe it.

Yet Asian Corridor in Heaven never got any traction outside of Korea, and disappeared completely, but with an afterlife online, subtitled in English. Why this depiction of one of the core strengths of Tibetan civilisation remains so unknown is a mystery.

CAN QUIET MOVIES CUT IT?

What hope have quiet movies, amid such hype? Whether directed by Tibetan Pema Tseden or Han Chinese Zhang Yang, the problem is the same: conflict and conquest are more cinematic than a quest for inner goodness. This is so from Gang Rinpoche’s first frames, in the cusp of the annual completion of the labour-intensive summer and autumn production cycle. The camera turns us to the undramatic but equally labour-intensive group winter work of pilgrimage.

Everyone does autumn harvest, but meanings differ sharply. When the Kham harvest is in, the barley threshed and ground, it’s time to change the agenda, a home truth embodied in the Chinese phrase 秋后算账 qiu hou suan zhang, “to balance the books after the autumn harvest”. However these days, in China, this has come to mean “to take revenge when the time is ripe”. The downfall of Tibetans is their optimism; the downfall of the Han is their fearfulness, as another old saying has it.

To go on nékor pilgrimage once the harvest is in is to do embodied spiritual practice. This is now unfamiliar to the modern world, whether Han, Western or Tibetans in exile, pursing the promise of modernity, of becoming a true self. Who these days has a whole winter to spare? We see the prostrators in action, but still struggle to see why they do it.

The lamas say “dharma practice is not just about working with the mind, but involves all aspects of us. In Buddhism, when we talk about self-transformation, it is not seen as purely mental. Self-transformation is seen as transformation of the totality of one’s being. One’s physical body, one’s vocal capacity, and one’s mind all become transformed simultaneously. In the West when we use the word ‘spirituality’, it has the connotation of contrasting with the corporeal. However, in Buddhism there is no tradition of seeing body and mind, corporeality and spirituality, in dualistic terms. Our body stores its own version of memory. Freeing the body of this is a way of transforming one’s body. Doing different practices that deal with the body frees it up.”[3]

Could it be that uneducated Khampa nomads know something urban sophisticates don’t? is their year-long pilgrimage just remarkable piety, or something more?

The film does take us through a full year, from winter to winter, and the filming actually took a year. This was a full-scale production in every way, with budget, crew, post-production all on industrial scale.

Yet it rose without a trace, failed commercially. Chinese audiences complained that nothing happens. In every scene an obstacle or challenge arises and everyo0ne readily agrees to just keep on prostrating. No drama. Why then did Gang Rinpoche fail with Tibetan audiences too? Pilgrimage is culturally familiar, even if today’s generation has other things on their mind.

Could it be the overtly Buddhist theme? Other movies steeped in Buddhism from beginning to end, such as Martin Scorsese’s 1997 Kundun, and Dzongsar Khyentse’s 2003 Travellers and Magicians come to mind as exemplary tales of Buddhist practice, and they have both become beloved classics.

Are Scorsese and Dzongsar Khyentse simply better story tellers? They deftly create believable characters more so than Zhang Yang or Pema Tseden.

Yet there is more to consider. For decades now, very few Tibetans growing up in exile have felt drawn to the inner path, be it monastic or as a yogic adept in the community. For decades, the rebuilt monasteries in India relied on Tibetans fleeing the father land, in order to pursue a religious vocation. When that stream ran dry over a decade ago, those labour-intensive monastic establishments were at a loss, only partially met by recruiting from the Himalayan belt.

There is no pilgrimage in exile, nor in a crowded world is it imaginable. There is the India circuit of the key holy places of the life of the historic Buddha, and many exile Tibetans immerse themselves in the Mon Lam intensive prayer season in Bodhgaya.

The gifted writer Tsering Wangyal Dhompa calls the lost father land, in the lives of today’s generation, as the miscellany under grandma’s bed, to be brought out occasionally, but increasingly remote, strictly for the old folks. Exile has gone too long, the new generation re-invented themselves, adapted to the speed of modernity, and moved on. Who has time these days for pilgrimage?

These may be why Gang Rinpoche, sometimes known as Paths of the Soul, disappeared before wider audiences could know it exists. Actually, it didn’t quite fail commercially, taking box office receipts of RMB 100 million, probably enough for the seven production companies investing in it to get their money back. It was also enough for director Zhang Yang, determined to continue his offbeat path, to get to make the 2019 Dali’s Voice, to some acclaim, even though it is shot entirely in a remote indigenous town, not far below Tibet, and privileges soundtrack over visuals, again confounding audience norms. Zhang Yang says this latest film grew out of Gang Rinpoche.

According to China’s business media: “The low-budget docudrama, “Paths to the Soul,” has been more profitable per screening than Hollywood juggernauts such as the latest “Transformers” movie, which opened in late June. “Paths to the Soul” raked in over 40 million yuan ($5.88 million), or nearly three times its production cost, during its first 11-day run despite being shown in less than 2% of theaters in the country.”

What is remarkable is that this movie resonated with an unexpected audience: urban China’s new generation of start-up entrepreneurs, those brave enough to plunge into the ocean of business, endure all difficulties, eat bitterness and eventually reap the rewards. They saw in the Tibetan pilgrims the same willingness to handle all challenges, and keep going. The pilgrims would be most unlikely to see themselves as eating bitterness, as they evidently take the world as it is, as it manifests. Yet the concept of eating or speaking bitterness has a long revolutionary history, and a contemporary usage. “During the Mao era, campaigns were organised in which people would ‘speak bitterly’ (suku) about the past, and ‘recall past bitterness in order to savour the sweetness of the present.’”[4] For Tibetans speaking bitterness was compulsory, meaning denunciation of revered lamas and disliked landlords alike, accusing them of profiting from the seat of the workers. Failure to speak bitterness could readily result in oneself being denounced and punished as a green brained lackey of the serf owners.

Today, it has shifted meaning. Now it means a willingness to undergo hardships in order to fulfil a great goal. For entrepreneurs out to disrupt business as usual, with visions ahead of their time, Gang Rinpoche was an inspiration, both for the new capitalists and to inspire their staff. That’s how Gang Rinpoche made some money. And then it quickly vanished.

No way would these pilgrims consider themselves to be eating bitterness; again Han and Tibetan understandings diverge. Same scene, different meanings.

There is, however, a tinge of bitterness in some Chinese responses to Gang Rinpoche. Qiang Ge, of the CCP Central Committee Party School in Beijing, a specialist in modernity in Tibet, has angrily asked why this movie takes China’s gifts to Tibet for granted, and fails to feature their key role in making pilgrimage possible. He has also accused Tibetan “peasants” of stubbornly resisting Chinas 1970s introduction of winter wheat as a new farmcrop, only to later benefit from it.[5]

Qiang Ge pointedly asks: “When you feel sympathy for the devout prostrating Buddhists, have you ever thought about those who paved the road upon which they kneel? Whether in artworks or when we travel through Tibet, we always see them prostrating with their heads on the road. But who actually built this road? It was built by generations of construction workers under the guidance of the Party’s leaders. I respect even more the construction workers who defied all setbacks and struggles; ‘Bitter sacrifice strengthens bold resolve/ Which dares to make sun and moon shine in new skies’ (a quote from one of Mao’s poems), that was their great spirit. In the Old Tibet, a pilgrimage by prostrating all the way to Lhasa did not exist. Because there was no road. Tibet’s topography was complex and arduous, it was even difficult for monkeys to cross many places on four legs, so it would have been even more difficult for people kneeling down. Secondly, pilgrimages did exist, but they were only made by a very small group of aristocrats.”

Qiang Ge, still advocating class warfare, seems as angry at the film maker as at the ungrateful Tibetans. It seems he has never seen Tibetans prostrating where there is no road, in the rubble of the lower slopes of holy mountains.

A young Tibetan intellectual in Tibet who calls himself Riga was also angry at Gang Rinpoche on its 2017 release, for the all-too-familiar reason that it reproduces a coloniser fantasy: “these seemingly benign images leave us bewildered as we begin to believe the myths that we are being sold. With Tibetan Buddhism more popular than ever, in China and the West, Tibet and Tibetans have become objects of the bourgeois Han imagination. Objects upon which their own longing can be inscribed. In the contemporary context, and especially in regard to independent filmmaking, depictions of Tibet are rooted in fantasies of a dissatisfied bourgeois class. Tibet becomes somewhere timeless and ahistorical, existing as an anachronism in which we may find an antidote to the disorientation of our modern secular condition. And by assuming the role of the passive observer we become participant in the commodification of our own culture. The dominant representation of Tibet sees filmmakers regurgitating tired stereotypes about Tibet. Celebrating Tibetan filmmaking might be best done by underscoring what is not unique to it.”

Fortunately, the entire Gang Rinpoche movie is freely available online, so judge for yourself.

There is one further reason why this movie rose without a trace, never engaging a Tibetan audience. It brings us back to genre. This is a drama in doco style. It’s this elision that seems to be the problem, a transgression of the boundaries of truth, and reality, and what counts as authentic.

This directorial decision is Zhang Yang’s original sin, dooming the entire movie. For many Chinese viewers, the doco format robs it of drama, and of emotional engagement with this character or that. It is merely an ethnic curiosity, an album of gestures and postures of difference.

Tibetan audiences, hearing the greatly differing dialects of the key characters, realised quickly that this is no doco, but a drama staged to look like a doco, making it inauthentic. Authenticity is bigger than ever in these times of essentialised identity. Zhang Yang’s genre bending is illegitimate, it seems.

Zhang Yang is not a director on the talk show circuit pumping his work; he prefers that his movies speak for themselves. Although he doesn’t say much, he has been very clear that this melding of drama and doco was a conscious choice, unlike his other movies before and since. When Gang Rinpoche was released, in 2017, Global Times noted: “Shot in the style of a documentary, Zhang used non-professional actors that he handpicked for the film, leading to a blend of scripted fiction and spontaneous reality. It is this method of depicting the group’s journey that has received the most criticism from moviegoers as some feel that a documentary format is not appropriate for a fictional story. Zhang Yang said ‘I think, on the contrary, this film presents another type of reality, which is what I wanted,’ Zhang said responding to the criticisms that a fictional pilgrimage should not have been filmed in a documentary style. He defended his decision by pointing out that even documentaries end up being edited to make a coherent story and that, in his opinion, those who are filmed are more or less performing in front of the camera. ‘My method is to rely on a documentary format to restore the truth. From my point of view, you can say that a director’s purpose is to present an artistic reality.’”

This is a direct challenge to our genre silos, our conditioned expectations. Zhang insists that the doco genre, for all its slice-of-reality hand-held authenticity is nonetheless sliced, into an edited representation. If fiction, as the saying has, is truth without facts, this film is a search for truth, a sun-beaten path Zhang Yang has trodden along with his cast. It was in every sense a long journey for all, starting in winter and ending in winter, reflecting the reality that filming did actually take a year.

Zhang Yang boldly asserts that reality and artfulness, far from being opposites, actually go together. This is a reminder of the Buddhist teaching that there is no pure, unmediated sensory perception; all we perceive is instantly mediated by our accumulated mental categories and concepts, so inseparably and immediately that what we hold dear as being authentic experience is actually conceptually framed. Zhang Yang’s framings unapologetically blur doco and drama, because that’s life.

Maybe the movie he did next, Up the Mountain, in a remote Yunnan village succeeded better in fusing art and reality, the authentic and the representation, direct perception and skilful editing. Inspired by Gang Rinpoche, Up the Mountain, 2018, got rave reviews, for good reasons, notably Zhang Yang’s painterly touch and skilful editing. But that’s another story, for another time.

The point surely is that Gang Rinpoche, the first full-length film to take prostration pilgrimage seriously, on its own terms, tries to show us not only the practicalities of prostration in all weathers, but to give us an inkling of the frame of mind required to persist, despite all challenges. Zhang Yang holds his mirror up for us to see not only the body and speech of prostration but also mind.

This matters, because prostration is the most photographed and least understood of all Tibetan behaviours. No tourist to Lhasa leaves without shots of prostrators in action, signifying only an inexplicably exotic behaviour that defies rationality. The snorting of a bull or scampering of a monkey are more explicable.

This is why Zhang Yang chose his cast, and, despite not wanting to say much, is quite upfront about how and why he did his casting, in much the way Chaucer cast his Canterbury Tales pilgrims. “In a press release for the film, Zhang explained that he already had a picture in mind of what he wanted to present on screen: First an old man in his 70s or 80s, who possible could die during the journey; a pregnant woman who would end up delivering her baby on the way; a butcher looking to atone for taking so many lives; and a child of about 7 or 8 who could add some interesting elements and uncertainty to the journey. He also wanted a mature and sober middle-aged man in his 50s who could act as the group’s leader. Having these characters in mind, Zhang and his film crew traveled through South China’s Yunnan Province and Southwest China’s Sichuan Province and Tibet until he met Tsring Chodron, a young pregnant woman whose father-in-law’s uncle had longed to go on a bowing pilgrimage his entire life. Soon after he found other local people who fit the bill for the characters he wanted to portray in his film.”

Once he found the pregnant woman, willing to give birth on the road, he knew he had a movie, the whole project could go ahead. She did indeed give birth on the road, in pain but unafraid. And the journey continued.

This is the mind of devotion as the path that clears all obstacles, inner, outer and secret. As Patrul Rinpoche says: “Devotion unlocks the door to all Dharma/ It clears the obstacles to all practice/ It brings out the benefits of all oral instructions/ It is offering a request to the guru’s completely compassionate mind/ and it becomes a vessel for all blessings/ It gathers the quintessence of all meditative accomplishments/ It is devotion –the singular, sufficient, pure remedy/ It can’t be conquered by any demons/ It can’t be stopped by obstacles/ It cleanses itself of all defiling stains/ It is devotion, and should be known as such/ It prevents the birth of false desires/ At the time of death there’s no pain of life suddenly cut short/ It pacifies the false appearances of the bardo/ It is devotion, and should be known as such.”[6]

This devotion is what Han domestic tourists are seldom able to comprehend, as they train their lenses on pilgrims at the Lhasa Jokhang flat on the ground in devotion, trust and faith, enacting the deepest sources of Tibetan strength.

So Zhang Yang may be one of the few Han Chinese to enter into Tibetan life, not as voyeur or ethnographer, but as a mirror, fully aware that he is an artist making artistic decisions throughout a movie of almost two hours, a self-knowing mirror.

Gang Rinpoche has its flaws, but it deserves better than a quick dismissal.

How is it possible a Chinese director can enter so fully into Tibetan life? Did he script it, or was the plot collaborative, in effect coming from the cast?

There’s precedent for that, for example Rolf de Heer’s Ten Canoes, a successful plunge into the lives of the Yolngu of far northern Australia. All de Heer had as a starting point was a collection of black and white carefully staged ethnographic photos taken almost a century ago by anthropologist and biologist Donald Thompson, who had posed Yolngu hunters in their bark canoes on the monsoonal wetlands, spears in hand. When de Heer showed up, Yolngu couldn’t at first relate to naked warriors in flimsy bark canoes out on the mosquito infested swamps; and, as Christians, they had no willingness to disrobe for the camera. Patiently, with a lot of workshopping, Yolngu warmed to the idea, coming up with lots of jokes, and an entire plot, which de Heer bought into. The result was an instant classic. It worked so well, there was a follow-up doco with the director telling the story of how it all came about.

Is this how Gang Rinpoche was made? Can we consider it a Tibetan film?

#gabriellafitte

[1] Chris Berry, Pristine Tibet? The Anthropocene and Brand Tibet in Chinese Cinema, 249-274 in K.-C. Lo, J. Yeung (eds.), 2019, Chinese Shock of the Anthropocene, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-6685-7_12

[2] The art of ethnography : a Chinese “Miao album” / translation by David M. Deal and Laura Hostetler ; introduction by Laura Hostetler., University of Washington Press, [2006

[3] Traleg Kyabgon, Integral Buddhism, Shogam, 2018, 39-40

[4] Jeffrey JAVED, 诉苦 Speaking Bitterness, in Christian Sorace, ed, Afterlives Of Chinese Communism Political Concepts From Mao To Xi, 2019, Verso & ANU Press, free download: https://press.anu.edu.au/publications/afterlives-chinese-communism

[5] 国家的策略性:农业技术变迁中的政治因素基于一个少数民族案例的研究, 社会 (Society), 2017, 37 (05): 78-104

[6] Dza Patrul Rinpoche, Plaeful Primers on the Path tr Joshua Schapiro, in Holly Gayley ed., A Gathering of Brilliant moons: Practice Advice from the Rimé Masters of Tibet, Wisdom Publications, 2017, 67