HYDRO DAMS ADVANCING UP THE RIVERS OF EASTERN TIBET

Will Tibetan rivers be saved from damming? We now know what China’s planners intend, in more detail than when the 13th Five-Year Plan was announced early in 2016. Now, at the end of 2016, China’s water planners have finalised their plans for that five year period, which runs through 2020.

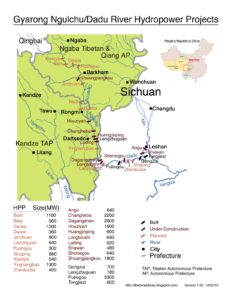

The news is not good. Plans to dam the Tibetan upper tributaries of the Yangtze are to go ahead, on what China calls the Dadu and Yalong rivers. Since these dams are meant to generate vast amounts of hydroelectricity, far more than could be used inside Tibet (even if copper mining is intensified), that in turn means the go-ahead for construction of a power grid to export electricity from the Tibetan Plateau, eastwards all the way across China to major cities including Shanghai and Guangzhou.

The combined impact of both dams and power grids, of all the construction crews and heavy equipment swarming up steep and remote valleys of Kham, eastern Tibet, will urbanise and industrialise the pastoral landscapes and pilgrimage circuits of Kandze and Ngawa prefectures.

Environmentalists have awaited this detailed blueprint, in the romantic hope that one wild river at least will be spared. They yearn to save the Nu, the remotest of all from lowland China, known to Tibetans as the Gyalmo Ngulchu and to much of the world as the Salween of Myanmar/Burma, hoping it can miraculously escape the fate of every other river in China. Recent attention has focussed on the omission of specific mention of the Nu in the latest official list of what is to be dammed, when and where. The exceptionalist dream still lives: the Nu has been spared, some say. In reality, even a strong state like China, capable of allocating capital expenditure to remote areas for nation-building, takes its time to match the engineering vision to concrete reality. Top priority for the next few years is the Dadu and Yalong, with no word as to when the planned dams on the Nu will feature on the list for a construction go-ahead. That’s a slender thread for romantic hopes to cling to.

The go-ahead for damming the Dadu and Yalong defies predictions that, by the time the dams are operational, and the ultra-high voltage power lines athwart Tibetan wilderness are all in place, coastal China’s factories will not need the additional power. This is because China no longer wants to be the world’s factory if that means manufacturing energy-intensive, water-intensive, low priced goods in highly polluting factories that pay low wages to workers, at a time when China plans to reduce energy intensity, graduate to being a middle income country and move its factories westwards towards Tibet, or to other countries with lower wages, such as Vietnam, Cambodia or Bangla Desh.

China’s coastal cities are also switching gradually –too gradually- out of coal-fired electricity, to less polluting natural gas, imported by giant tanker ships. For all these reasons, the predicted energy shortage necessitating Tibet to be remade into a major electricity exporter may not be needed.

On 30 November 2016, China’s National Energy Administration (NEA) released its work plan, fleshing out the Five-Year Plan in detail. Official China’s fixation on nation-building mega projects continues. The NEA announces it will “Speed up inter-provincial transmission project in particular, hydropower, wind power delivery channel construction, increase the proportion of clean energy utilization.” China’s ongoing reliance on dirty energy, primarily coal continues, despite much official rhetoric about reducing reliance on coal. China continues to burn more coal annually than the rest of the world combined. That is the rationale for the turn to wind, solar and hydro, on the assumption that they are not only clean but unproblematic. NEA announces it is mindful that China’s West, including Tibet, is officially designated as the new zone of energy-intensive industries, a shift inland from the coast: “Promote energy and energy-intensive industrial development. Implement the ‘State Council guidance on the central and western regions to undertake industrial transfer,’ the western region to support the implementation of energy-intensive industrial layout optimization project.”

So it announces as its target a strong growth in hydro power generation: ”The National Energy Administration officially announced its’ hydropower development plan for the thirteenth Five-Year Plan. The plan shows that in 2020 China’s total installed capacity of hydropower 380 million kilowatts, of which 340 million kilowatts of conventional dams, pumped storage capacity of 40 million kilowatts, the annual generating capacity 1.25 trillion kwh, equivalent to about 375 million tons of standard coal. Experts said that to promote the rational development of hydropower, not only will effectively protect China’s clean power supply, will also promote China’s economic and social development. According to statistics, China’s potential hydropower resources can be further developed and installed capacity could reach about 660 million kilowatts, the annual generating capacity of about 3 trillion kWh, second only to coal. After years of development, China’s hydropower installed capacity and annual power generation has exceeded 300 million kilowatts and 1 trillion kWh, accounting for 20.9% and 19.4% of total electricity production.” (Economic Daily News, Dazhong Xiao, 30 Nov 2016)

This requires an increase in generating capacity from 300 to 380 mkW, a jump of 27 per cent. That’s by 2020, with an even bigger jump in the following five years. There is only one area where such a leap is possible: Tibet, especially on the eastern margins of the Tibetan plateau, where Asia’s great rivers cut steep valleys, flowing as wild mountain rivers, until now unimpounded. Capturing Tibetan rivers is known in China as the “West-to-east electricity transfer program.” NEA says: “Plan the next step to continuously expand the “West to East” capacity, in 2020 the scale of hydropower transmission to 100 million kilowatts. It is estimated that in 2025, the national hydropower installed capacity will reach 470 million kilowatts, including 380 million kW of conventional hydropower, 90 million kW of pumped storage and 1.4 trillion kWh of electricity annually.”

The hydro dams athwart Tibetan rivers have been planned for decades, but actually building them will take time, hence the time frame spanning two Five-Year Plan periods, to 2025. By then, the plan is far beyond the 27 per cent increase on present hydro power generating capacity. From the current baseline of 300 mkW to 470 mkW, is a jump of over 50 per cent in ten years. Only Tibet could possibly contribute this much electricity to China’s factories and cities.

The NEA plan is quite specific: “Taking Southwest China, Sichuan, Yunnan, Tibet as the focus, focusing on major projects, combined with the end of the market and delivery channel construction, and actively promote large-scale hydropower base development. Continue dam construction on the Jinsha River, the Yalong River, Dadu River and other hydropower base construction work; actively promote the Jinsha River and other hydropower base construction, construction of the southeast of Tibet, “West to East”. By 2020, the conventional hydropower installed capacity in the western region will reach 240 million kilowatts, accounting for 70.6% of the national total, and the development level will reach 44.5% of total potential dam construction.”

The specific targets are on the Jinsha and Dadu rivers of Kham. The Nu is mentioned, as well as the Yalong Tsangpo/Brahmaputra, but not as specific targets for energy extraction within the current Five-Year Plan period. Both are named as rivers for which ongoing planning of future dams is to go ahead.

ABUNDANT WATERS OF A LAND OF POVERTY?

NEA also emphasises doing its part in attracting the intractably poor to relocate to districts where electricity will be made available. China’s 13th Five-Year Plan ambitiously declares all poverty will be eliminated by 2020, even though the remaining poor are clustered in areas so deficient in the factors of production that poverty in situ is impossible to overcome. This is a scientistic way of saying poverty is endemic in Tibet, because Tibet is high, cold and lacking all that China finds familiar. China assumes no-one would live in Tibet if they had a choice, so removing people elsewhere, especially if elsewhere is on a mains electricity grid, is doing them a favour. NEA announces it will provide: “full support for poverty-stricken areas of energy resources development and utilization, implement the spirit of the central anti-poverty work conference, insist on accurately targeted poverty, precise identification of those to be lifted out of poverty, efforts to speed up poverty-stricken areas of energy development and construction, focus on improving the local energy universal service levels, and promote economic development in poor areas and improve people’s livelihood, to win the battle of poverty. Implementation of the ‘National Energy Administration Opinions on Accelerating the development and construction in poor areas to promote energy poverty out of poverty’ and to increase energy projects in poor areas to support and capital investment, new energy development projects and delivery channels, give priority to ethnic minority areas, border areas and contiguous destitute areas layout.”

NUMBER ONE WATER TOWER

All of China’s plans are based on the idea that “Tibet is China’s Number One Water Tower”, a slogan invented by Qinghai hydro engineers decades ago to try and attract Beijing’s attention, and funding, to a province that was languishing. Like all official slogans, it has been repeated so often it has become a truism, something known to be true because it is known to be true. But is it? The Tibetan Plateau is indeed a great island in the sky, towering above lowland China, its waters falling freely.

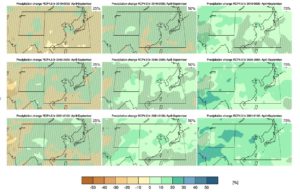

But Tibet gets less rain than most of China, and can even be considered semi-arid, especially upper, or western Tibet. At least that was the case until climate change and glacier melt started to make a big difference. Now the most arid parts of Tibet are experiencing increased rainfall, as well as glacier melt, and as a result the lakeland of the Changtang is expanding. The empty northern plain, or Changtang, is where Tibetan civilisation began, thousands of years ago, with archaeologists recently finding ancient irrigation channels traversing what today is stony desert. The vast Changtang is dotted with lakes; all have inlets but no outlets. The water level in these lakes has been very slowly dropping for thousands of years in a long term shift of climate that eventually pushed the Tibetans further east, to better-watered areas, to Amdo and Kham, in today’s Qinghai, Gansu, Sichuan and Yunnan provinces. Scientists have intensively studied these falling lakes, which often are ringed by ancient benched beaches now perched high above the water line.

Until now. Early than usual spring rains, further penetrating monsoon rains, even late autumn rains are now filling those lakes higher than ever, a reversal that became noticeable only this century, after thousands of years of gradual desiccation.

This year’s monsoon rains were especially striking. 2016 seemed in many ways similar to 1998, the last time there were major floods on the Yangtze. The 1998 floods were serious enough for China, at the highest level, to recognise it could continue to plunder the forests of Kham only at great cost to downriver Chinese cities on the Yangtze floodplains. The result was China’s switch from exploiting the forests of Kham to exploiting Burma and further afield, taking the tropical forests of SE Asia, the islands of the Pacific and Africa instead.

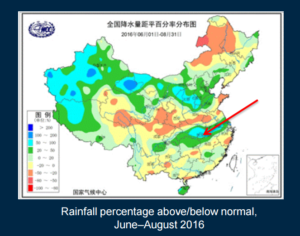

But the Yangtze floods of 2016 did not originate in Tibet; in fact the headwaters of the Yellow (Huang He in Chinese, Ma Chu in Tibetan), Yangtze (Chang Jiang in Chinese, Dri Chu in Tibetan) and Mekong (Lancang in Chinese, Za Chu in Tibetan) actually had a very dry year, with rainfall totals sharply down. Meanwhile, far western upper Tibet had one of its wettest monsoons ever, with rainfalls far above what is usual. Things are changing fast. The lakes are rising. By the time all those hydro dams are built, much of the “dividend” of extra flow from glacier melt will be past, and if 2016 is repeated, there may not be enough water to turn those expensive hydro dam turbines for more than a few months each year.

So there is still reason to believe that, if dam construction can be delayed a few years longer, the hydro engineers will rethink their data, and realise they left it a bit late to concretise their dream of capturing all of Tibet’s rivers.