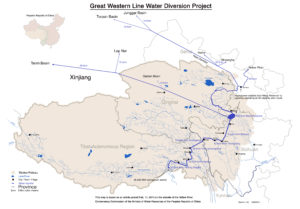

WATER DIVERSION ON A MASSIVE SCALE, FROM TIBET TO LOWER CHINA

#3 in a series of 8 blog posts on China’s latest plans for Tibetan rivers

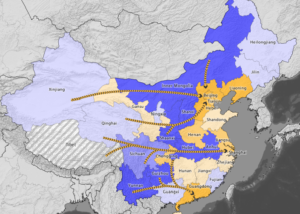

China has long planned to channel billions of cubic metres of water from the Tibetan upper Yangtze (Dri Chu in Tibetan) in order to pump water into the depleted Yellow River.

The three specific routes officially planned are now poised to begin construction, if the recent announcement of “big reservoirs in Tibet”, on the list of 13th Five-Year Plan targets is implemented.

Tibetan river waters have become, to China, even more desirable than its forests, grasslands, livestock or minerals, most of which fail to “come out” to China’s satisfaction, or are in decline, due to official bans.

What will be the impact on Tibet if these three south-to-north (S2N) water diversion projects, with their big reservoirs, tunnels and canals, are built, across the most troubled regions of the Tibetan Plateau?

If all three S2N western river diversion projects are built, and work as well as planned, sending 20 bn m3 more water into the Yellow River, this will be a major boost to an exhausted Ma Chu/Huang He/Yellow River, which, at Lanzhou, not far beyond the Tibetan Plateau, has a mean annual runoff of around 35 bn m3. On paper, the extra water from Tibet, taken from the upper Yangtze, could boost the yellow River by 50 per cent or more. However, even this boost would do nothing for the lower Yellow River, as all the benefits will have been captured by midriver users.

WILL THESE BIG RESERVOIRS BE BUILT?

There are cogent reasons to suppose that since the 13th Five-Year Plan for 2016 to 2020 has announced big reservoirs will be built “in Tibet and other areas” which China no longer thinks of as Tibetan, that the go-ahead signals their inevitability. Some observers suppose that an official announcement is in itself proof that the project will proceed as planned. However, China is not monolithic, and it is not the case that central leaders have only to snap their fingers and their command is implemented.

The official announcement, part of a long wishlist of official projects, has been long on the drawing board, and may yet fail to eventuate, for reasons of technical difficulty, expense, insufficient return, or lack of customers willing to pay for the construction cost recovery. So it is worth looking more closely at the reasons, for and against, to reach some estimation of whether it will happen.

China’s first plan to intercept the upper Yangtze was in 1932, in a report that six decades later led to the construction of the Three Gorges Dam.[1] The Three Gorges Dam, intended to provide not only a massive boost to hydropower generation but also add hundreds of kms of navigability, remains the most decisive human intervention on the Yangtze, also the most contested. Since its completion, the grand vision of the Yangtze becoming a shipping highway extending China’s coast thousands of kms inland, has not been realised. That is the focus of another 13th Five-Year Plan project.[2] That it took eight decades of planning and construction is an indication of the size and complexity of major hydraulic engineering schemes. Here are seven reasons why S2N Western Route may already be past its’ sell-by date.

CONTRA

There are many reasons to suppose S2N Western Route will not be built, or not for a long time. Three Gorges required a powerful patron at the very highest level to push it through, and in its wake, enthusiasm for huge projects has waned.

1 CLIMATE CHANGE: The stripping of the forests of eastern Tibet has increased the inflow of water to the many Tibetan tributaries of the upper Yangtze, and the climate change trend also increases rainfall, while climate warming is melting the glaciers at the source of many Yangtze sources in Tibet. While this increases overall flow, it also concentrates that flow more in the summer months, exacerbates the danger of flooding (one of the key arguments for building Three Gorges) and also increases sedimentation which may greatly reduce dam water retention capacity, as sediment load carried along by fast flowing mountain rivers is slowed and stopped by big reservoirs. These combined impacts suggest that even though the Yangtze is a massive river, far bigger than the Yellow River, it will be very difficult to capture sufficient water to make much difference on the Yellow River at the times of year when water is most needed.

However, when one takes a more long-term view, as climate scientists do, towards the end of this century, the trend is for rainfall in the upper Yangtze (UYRB) to gradually decline, especially in summer. Scientists warn that climate change could “reduce runoff in the UYRB and exacerbate water supply problems in the region.”[3] Runoff in summer months could reduce by as much as 15 per cent, and in autumn by 10 per cent.

2 COST/BENEFIT: Unlike statist nation-building projects in Tibet such as railways and highways, paid for by central party-state funds with no expectation of recouping costs, water users throughout China do pay and are expected to pay sufficiently to recover the costs of S2N Western Route construction, even if repayment is over a longish period. The cost of water has historically been kept low, both to encourage its (wasteful) use in agriculture and as a low cost industrial input. Even if farmers are incentivised to use water more carefully, by increasing its cost, there is no way peasant farmers will be able to bear the costs of S2N Western Route, and this is acknowledged by advocates of the project.

3 COMPETING USES: Water diversion competes with hydropower generation. China is committed to increasing renewable energy as a proportion of total energy consumption, to make its annual burning of more coal than the rest of the world combined more acceptable internationally. Hydropower is the oldest renewable energy technology, but in the mountains of eastern Tibet, the steep valleys are to be used for both eater diversion and electricity generation, but not in the same spot. Meeting China’s renewable energy target requires investment not only in hitech wind and solar power, attracting great interest from investors, but much less fashionable hydropower. Dams can be designed to provide both hydropower and for diversion of water elsewhere, but in most situations it is one or the other. For example, on the Tibetan Plateau so far, water impoundment for diversion to farmers or distant users has not been done, and all dams have been to hold water only as long as is needed to turn turbines and generate electricity, a design usually known as run-of-the-river.

Even on long rivers in the mountains, with steep valleys well suited to dams, there is still only a limited number of sites suitable for dam construction. On Tibetan rivers, endless cascades of dams have long been planned, with many built and many more due for construction; all of them until now being for hydropower. On the Yarlung Tsangpo a series of six dams below Tsethang in southern Tibet is planned with one, the Zangmu dam, in operation. This area is on the same stretch of river once proposed, by retired PLA officers, as the best location for a massive water diversion scheme, far bigger than S2N Western Route, that would eventually reach the Yellow River. The fact that a string of six hydro dams is under way in this district means there can be no water diversion. Doing both is not possible.

Hydropower from the planned dams in eastern Tibet does have customers, far away in coastal China, in major cities such as Guangzhou and Shanghai, willing to pay for the electricity generated on Tibetan rivers and transmitted by ultra-high voltage cables (with little wastage) right across China from west to east. By comparison, the main beneficiaries of S2N Western Route water diversion will be in poorer and more remote areas, with less political clout. Fully 33 percent of China’s population lives in the Yangtze catchment.

At the Three Gorges Dam, and all the way to the coast, is another competing use: a Yangtze with enough water for sizeable ships to ply up and down. This was always one of the promised benefits of the  Three Gorges Dam, which created a lake hundreds of kms long, stretching all the way to the boom city of Chongqing. While the main Three Gorges Dam was completed a decade ago, it was only at the end of 2015 that the final stage, of completing the lock enabling biggish ships into and out of the Three Gorges lake finally came into operation. Now Chongqing industries expect access to global markets for their manufactures, down the Yangtze. The central party-state has responded by announcing the Yangtze River Economic Belt project, a major investment in bringing prosperity to the middle and upper Yangtze, but not to Tibet.

Three Gorges Dam, which created a lake hundreds of kms long, stretching all the way to the boom city of Chongqing. While the main Three Gorges Dam was completed a decade ago, it was only at the end of 2015 that the final stage, of completing the lock enabling biggish ships into and out of the Three Gorges lake finally came into operation. Now Chongqing industries expect access to global markets for their manufactures, down the Yangtze. The central party-state has responded by announcing the Yangtze River Economic Belt project, a major investment in bringing prosperity to the middle and upper Yangtze, but not to Tibet.

4 ENVIRONMENTAL CONCERNS: The amount of water to be withdrawn from the Yangtze by S2N Western Route, even the full 20 bn m3, as planned, will make little difference in the midst of the summer rainy season, but at other times of the year it could be more problematic.

As popular Chinese worries about environmental damage grow, with fears about the purity and safety of food, air and water, there is widespread concern about water diversion in an upstream area officially represented as pure and even pristine.

Large dams –whether for hydropower or water diversion- disrupt environmental flows, interrupt the paths of breeding fish and other fauna, and in Tibet may trigger earthquakes and massive debris flows, as eastern Tibet is a highly active seismic activity zone, and dams are often on fault lines, unable to bear the extra load of impounded water, which seeps down a long way, lubricating faults straining against each other.

Officially, the planners of the central party-state make light of such dangers, as they do of the concerns of local populations who, by Chinese standards, are small. But the concept of environmental flow, of a river maintaining its natural seasonal rhythm, is growing, and there have been several popular mobilisation campaigns to protest at dam builds, some successful.

Chinese scientists have identified rare fish species in these upper Yangtze rivers, whose lifecycles will not only be blocked by the many dams planned, but also, below the hydro dams required to generate the electricity to pump water uphill, the water that spills out after turning the turbines, has a higher level of atmospheric gases in it than the fish can take.[4]

As evidence accumulates, at a time when urban Chinese strongly want conservation of pristine landscapes, if only as authentic tourism destinations, the concerns of scientists can become popular concerns.

5 AN INVESTMENT CAPITAL SHORTAGE: China has bankrolled any number of massively expensive infrastructure construction projects in Tibet, so it might seem strange to suggest the flow of subsidies and capital expenditure on grand projects could ever end, or even slow. China has been committed to “leap-over” development in Tibet Autonomous Region for nearly two decades, and seems ever willing to pump in more money. The result is that, on paper, GDP is growing fast, even if ordinary rural Tibetans remain poor, and benefit little from the capex spend. This all looks good on paper, China can boast that the TAR economy continues to grow rapidly and all is well. In the first quarter of 2016, many provinces grew only minimally, while Liaoning, reliant on yesterday’s heavy industries, actually fell. Only two provinces reported ongoing fast growth: Chongqing and TAR. Both reported 10.7 per cent growth.[5]

What drives the Chongqing economy to grow so fast is not hard to explain. But TAR? As Andrew Fischer has explored in great depth, the TAR rate of growth is almost entirely artificial, driven by central subsidies with very little rate of return if judged purely economically. The payoff is not monetary, but in extending the reach of the state, the establishment of sovereignty over all of Tibet. These are the expenses of nation-building, and are set to persist whether they make economic sense or not.

Yet China could find itself constrained, in ways that are barely imaginable at present, by the consequences of the huge accumulation of debt, and investment in projects that fail to generate a return. One to three years from now, some predict, the crunch will come, and China will have to settle for a period of no growth, until the mess caused by excessive credit, excessive stimulus and excessive investment in unproductive assets all get painfully sorted.

“Many are now concerned that China’s debt could lead to a so-called balance-sheet recession — a term coined by Richard Koo of Nomura to describe Japan’s stagnation in the 1990s and 2000s. When corporate debt reaches very high levels, he observed, conventional monetary policy loses its effectiveness because companies focus on paying down debt and refuse to borrow even at rock-bottom interest rates.

“A financial crisis is by no means preordained but in our view, if losses don’t manifest on financial institution balance sheets, they will do so via slowing growth and deflation, à la Japan, a path China arguably already is on,” Charlene Chu, senior partner at Autonomous Research Asia, wrote recently.

“Every major country with a rapid increase in debt has experienced either a financial crisis or a prolonged slowdown in GDP growth,” Ha Jiming, Goldman Sachs chief investment strategist, wrote in a report this year.”[6]

In such constrained circumstances, there may be greater financial discipline and less occasion to splash money on grand projects that may have a political payoff, but no economic justification. However, China’s determination to remake Tibet, with Chinese characteristics, suggests politics will always trump economics, at least in Tibet Autonomous Region.

6 REDUCED COAL INDUSTRY DEMAND FOR WATER Coal remains highly contentious in China, primarily because it is irremediably dirty, polluting the air of most Chinese cities, and also because the coal industry has an appalling safety record. It may yet be that, despite delegating decision-making to subnational governments, China gets serious about reducing coal use, if only to avoid chronic problems of over-capacity in many industries that rely heavily on coal, notably steel. The Ministry of Water Resources may finally succeed in regulating coal industry water use.

7 SCIENTISTS AND ENVIRONMENTALISTS MOBILISE TO OPPOSE BIG RESERVOIRS

Prof Wang quoted above, and the scientists who found rare fish in the specific area to be dammed[7] are among the familiar Chinese pattern of scientists at the forefront of familiarising Chinese audiences with remote locations in Tibet, and what is special about them if untouched. Sometimes these scientific reports and the scientists themselves, who increasingly feel protective of the areas they have studied, gather momentum, and a movement gathers energy to politely but persistently argue against official plans for big dams and reservoirs. Such campaigns, if done skilfully, and with good inside channel connections to high-level decision makes, are sometimes successful, even in the current highly authoritarian situation.

Another example of scientists complicating the narrative of the hydro engineers is the study of the earthquake history of planned dam locations, highlighting the risks that dam advocates brush aside. One example is the Suwalong Dam in Kham, on the Jinsha, one of China’s names for the upper Yangtze, where, between the Tibetan towns of Batang and Markham, it cuts a deep valley. The valley walls are actually so steep, and the valley so deep that it receives little rain and has little vegetation to bind the soil, so there have been massive landslides that in turn have dammed the upper Yangtze, only to have these huge natural dams later burst disastrously. Careful scientific work recently has shown that 1900 years ago and again 1355 years ago enormous landslides blocked the Jinsha, then, 200 years later, a major earthquake liquefied the water-laden earth holding back the Jinsha, leading to a catastrophic collapse of the lake. [8] Such scientific rediscovery of earthquake histories might make planners pause.

When it became clear, in 2013, that under Xi Jinjping accelerated construction of big dams on Tibetan rivers was to resume, a coalition of environmental NGOs formed, to collectively issue a detailed argument for sparing the Tibetan rivers from intensive extraction of both water and hydropower. The 19 NGOs, with long experience of campaigning to save Tibetan rivers, issued a detailed 88 page report in Chinese and in 2014, a 17 page summary in English. [9] These NGOs have much experience in calmly speaking up for nature, even in repressive times, as they know from experience what can be said, and how to say it, within the bounds of acceptable discourse. This small constituency of advocates for nature, and for the indigenous communities who have long protected nature, are in many ways the only Chinese who have become familiar with remote Tibetan landscapes, other than the Chinese surveyors and engineers who went to Tibet to plan its exploitation.

In keeping with past successful campaigns to save rivers from dams, such as the Nu River campaign of 2004, the environmental NGOs, and their well-connected and respected scientists, arranged to meet with senior decision makers to put their case. “In November 2013, we were invited to two internal consultation meetings on Yangtze River Basin’s planning and management, held by the National Development and Reform Commission’s Energy Research Institute.” Diplomatically, they state: “These meetings provided us with valuable insights into the new Administration’s efforts to balance basin development and conservation. We left the meetings with new ideas and more optimism on better water governance in China. The health of China’s people and economy is tightly linked to the health of the country’s rivers. We hope this report will help stimulate new efforts and dialogues on balancing river development and conservation, new institutions enforcing public participation, new emphasis on implementing “ecological redlines.” We also hope to ensure that the pursuit of renewable energy and pressures to reduce greenhouse gas emissions does not sacrifice the multiple values of rivers.”

Nonetheless, as the 13th Five-Year Plan is rolled out, it seems the dams and reservoirs are to go ahead. The environment movement did succeed, largely through the 2004 campaign over the Nu river, to obtain (in hindsight) a decade-long moratorium on dam building. But, if the 13th Plan is implemented, massive infrastructure spending on dams and reservoirs is back on the agenda.

China’s environmentalists, in the longer term, have time in their side, as more Chinese, often well educated, get to see remote areas for themselves, and speak up for nature, for Tibet, and implicitly for the Tibetans who may not form their own NGOs. When these skilful and experienced NGOs remind everyone that “the health of China’s people and economy is tightly linked to the health of the country’s rivers,” this quiet expression of obvious truth reminds a much wider audience what matters in the longer term.

More than a decade ago Chinese environment scientists, NGOs and Tibetan communities created a mass mobilisation campaign that successfully stopped official plans to hydro dam the Gyalmo Ngulchu/Nu/Salween river. That story is told in a later blog in this series. Can such a coalition of ethnic minorities and Beijing intellectuals happen again, in today’s more repressive circumstances?

REASONS WHY THE RESERVOIRS, DAMS AND TUNNELS WILL BE BUILT AS PLANNED

While China is no longer totalitarian, and official plans are often delayed, or even fail to materialise, there are many vested interests pushing for the capture of Tibetan rivers, none more so than the official Yellow River Conservancy Commission. Many arguments are made for pressing ahead with all the planned dams and reservoirs, not only to benefit mid-Yellow River industries, notably coal, but even to deal with the dangerous build-up of silt in the bed of the Yellow River further downstream, on the North China Plain, cradle f China’s civilisation.

1 SAVING THE YELLOW RIVER FROM FLOODING THE NORTH CHINA FLOODPLAIN

S2N Western Route has been on the wishlists of central planners for decades.

A 2015 book by a leading hydrologist, Zhao-Yin Wang, puts the debate over the future of the lower Yellow River into wider context of dealing with the opposite danger to the absence of water: the danger of floods, which has long been the reason why this river, with its huge burden of yellowish sediment from incising its way across the Tibetan Plateau, has for so long been known as “China’s Sorrow.” Prof Wang shows that the flooding danger is now less than before, but the sediment load, now captured in the reservoirs where water stops moving and drops its load, is still problematic. He looks at the prospect of flushing the lower Yellow River with seawater to scour out the accumulated sediments. The idea has been considered for the past 20 years, and would involve pumping seawater uphill, though nowhere near as high as in the Nga Chu/Dadu S2N Western Route proposal. Prof. Wang looks at deliberately engineering a “hyperconcentrated flood” to flush out sediments that in places make the river bed higher than the surrounding land.

Finally he looks at “Interbasin Water Transfer Projects”, which means the S2N Western Route. He is optimistic that it will not only provide more water but also sufficient water, even in the lower Yellow River, to flush out to sea the dangerous accumulation of sediment. He writes: “The water shortage in the Yellow River basin was estimated to be around 7 billion m3 in 2010 and 15 billion m3 in 2030 (Chen, 1991). The main strategies to solve or ease the water shortage and save the river from dying out are reallocation of water resources and interbasin water transfer projects. Three routes of South–to–North Water Transfer Projects have been proposed and will be implemented. The West Route will transfer water from the Qinghai-Tibet plateau to the upper reaches of the Yellow River. The west route of water transfer project will transfer water from the Jinsha River (the Yangtze River), Yalong River, and the Dadu River to the upper Yellow River. About 1.95 billion m3 water can flow to the Yellow River by building dams and tunnels. The water shortage problem of the Yellow River basin can be solved and the clear water may carry sediment into the sea, thence the siltation of the river channel can be stopped. Nevertheless, the ambitious project needs a lot of investment. The Jinsha, Yalong and Dadu Rivers are only 100–200 km from the upper Yellow River. The total annual runoff of three rivers is 120 billion m3. The project can divert 19.5 billion m3 water from the three rivers to the Yellow River.”

Prof Wang acknowledges that the plan is to intercept high mountain tributaries of the Dadu/Nga Chu, which in turn is a tributary of the Yangtze, in order that the water diversion tunnels start as close as possible to tributaries of the Yellow River. On the tributaries due to be captured and diverted, as much as half their stream flow will be lost, and this “will impact the local ecology. It is necessary to study the impacts of water diversion on the local ecology and take measures to mitigate the impacts as the water diversion is implemented.”[10]

- THE TIBET DIVIDEND There is a widespread perception in China, cultivated by official media, that Tibet has been generously supported by richer provinces, which have poured money and manpower into lifting the backward Tibetans up, but without much payoff. In this view, not only does Tibet remain backward and unproductive, little comes out of Tibet, and it is time China’s huge investment in Tibet paid a dividend.

Although China long expected the profit-making “pillar industries” of Tibetan economic take-off would be minerals, mass tourism, meat and timber, most have failed to materialise, or are already exhausted. It turns out that the most precious commodity Tibet has in super abundance (in this lowland view from below) is water, that just goes to waste unless it is dammed, captured, channelled and tunnelled for use in northern China, or to turn hydropower turbines (or both).

Now that then army of water canal construction engineers have completed the south-to-north canals and tunnels across eastern and central China, it is time to turn to the S2N Western Route. That was the plan all along. It has taken three successive Five-Year Plans to build those lowland canals, now is the turn of the Tibetan prefectures of Kandze and Ngawa, in eastern Tibet.

So valuable is the water of the upper Yangtze and upper Yellow Rivers, that all else can be sacrificed to ensure watershed protection. Even if that means shutting down the pastoral production landscapes, cancelling nomadic herder land tenure entitlements, displacing hundreds of thousands of nomads, it is worth it if the result is that more grass grows, thus protecting what really matters most to northern China, the degrading watersheds far above.

[1] Yang Guishan et al., Yangtze Conservation and Development Report 2007, Science Press, Beijing, 7

[2] Political Bureau of CPC Central Committee passes two documents, Xinhua | 2016-03-26

[3] Jialan Sun, Xiaohui Lei, Yu Tian, Weihong Liao, Yuhui Wang; Hydrological impacts of climate change in the upper reaches of the Yangtze River Basin, Quaternary International 304 (2013) 62-74

[4] J. Feng, R. Li, R. Liang, and X. Shen, Eco-environmentally friendly operational regulation: an effective strategy to diminish the TDG supersaturation of reservoirs, Hydrology and earth System Sciences, 18, 1213–1223, 2014

[5] Lucy Hornby China province falls into negative growth: Liaoning is first regional economy to shrink in seven years, Financial Times 28 April 2016

China’s Provinces Take Aim at Moving GDP Target, Wall Street Journal, Jan 29, 2016

[6] Gabriel Wildau and Don Weinland, China debt load reaches record high as risk to economy mounts: US-style credit crunch or Japan-style grinding malaise seen as increasingly likely, Financial Times, APRIL 24, 2016

[7] J. Feng, R. Li, R. Liang, and X. Shen, Eco-environmentally friendly operational regulation: an effective strategy to diminish the TDG supersaturation of reservoirs, Hydrology and earth System Sciences, 18, 1213–1223, 2014

[8] Pengfei Wang , Jian Chen, Fuchu Dai et al., Chronology of relict lake deposits around the Suwalong paleolandslide in the upper Jinsha River, SE Tibetan Plateau: Implications to Holocene tectonic perturbations, Geomorphology 217 (2014) 193–203

[9] https://www.internationalrivers.org/china%E2%80%99s-last-rivers-report

[10] Zhao-Yin Wang, Joseph H. W. Lee and Charles S. Melching, River Dynamics and Integrated River Management, Tsinghua University Press, Springer, 2015, 392