ON THE ROAD, IN YOUR DREAMS

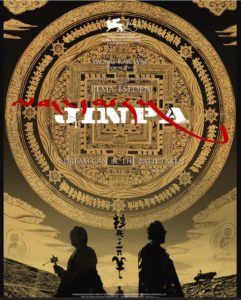

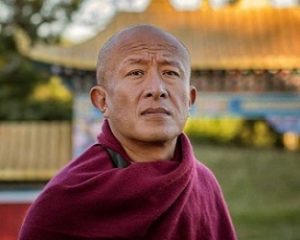

Film maker Khyentse Norbu aka Dzongsar Jamyang Khyentse Rinpoche, has inspired and shaped a 2021 movie, shot inside Tibet, that vividly shows how an advanced tantric practice -dream yoga- frees the mind of its literalism, and habitual addiction to facticity.

The title alone says a lot: Bipolar. That immediately evokes the madness of swinging between extremes, with no sure footing. Yet, far from madness, the practice of dream yoga is the circadian interplay of dream and awake, admixed to loosen our usual privileging of the diurnal over the nocturnal. “It’s just a dream” we say when we wake shaking it all off, ignoring the playful, endlessly creative versions of my life. Then we get on with living in the real world, with its real facts, real categories, real decisions, all of them based on unexamined and arbitrary reductive editing of fluidity.

Dream yoga invites us to treat being awake as a dream; then at night to treat dream as reality, a technique that not only dissolves those sharp distinctions, it makes for a more fluid, open-minded way of living. In today’s world, beset by ideologies, everyone obsessing about identity at both personal and national levels, a bit more fluidity might help. A bit of bending of categorical imperatives might be useful.

That is what Queena Li’s Bipolar does. Only a visual medium -film- could mix dream and daily life so well, in a road movie heading out of Lhasa across Tibet, Yunnan and Guangxi, towards the ocean closest to Tibet, ostensibly on a mission to return to the sea a lobster first met in the Lhasa Intercontinental in a glass tank, awaiting its fate as the dinner choice of a rich man, having been flown in for the purpose of conspicuous consumption.

That is what Queena Li’s Bipolar does. Only a visual medium -film- could mix dream and daily life so well, in a road movie heading out of Lhasa across Tibet, Yunnan and Guangxi, towards the ocean closest to Tibet, ostensibly on a mission to return to the sea a lobster first met in the Lhasa Intercontinental in a glass tank, awaiting its fate as the dinner choice of a rich man, having been flown in for the purpose of conspicuous consumption.

Instead, our central character hijacks the sacred lobster and hits the road. Lhasa, the iconic locus of enlightenment, did not deliver on cue as expected, a reminder that what we seek is seldom where it’s supposed to be. So to the road, on a journey with no end, as it’s the journey, not the destination, that matters.

Director Queena Li says: “The girl in the film goes on a pilgrimage. She’s seeking spiritual answers. Lhasa is a very typical place to do that. It’s a classic motive. When we find the answers not in the place where we thought we will find them, we set off in the next direction. It’s only after she leaves Lhasa that she starts her real pilgrimage.

“I’m interested in combining the illusionary, and the dreamy with what you can call real. I guess it’s similar to my life. I’m hastily daydreaming through it. The story brings together all kinds of different metaphors, from fairy tales to local Tibetan sagas. I tried to reflect on my life and the area where the film takes place in Tibet through different lenses.”

Reviewers of Bipolar so often call it “weitd”, so much so that in interviews you see Queena Li (Li Mengqiao) wince in expectation. We can take only so much gender bending, and dream/reality bending, without a steady post to hitch our horse to.

Queena Li calls Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche her mentor, with a big role in writing the screenplay, and a bit part onscreen as a bald seller of wigs. Nothing transforms the persona as quickly and wholly as a wig, a classic Khyentse Norbu storytelling way of teaching the Buddhadharma, inviting us to be more playful.

Queena Li and Dzongsar Khyentse have a heart connection. She says: “He’s my mentor and I simply love his work. Initially, I wanted to make this film in Canada, where the novel [Hasting Express by Gosha Wen] takes place. But then, Norbu told me that it’s better to do it in Tibet. There is a quote from one of his books in my film: “True surrealism is to see your whole mind”, which shines a very important light for the message of Bipolar. He also appears in the film as a wig seller and his dialogue with Leah’s character really fits him as a person, as it’s full of wisdom. Well, you can say that he’s like that in real life.”

Dream yoga, rmi lam, one of the six yogas of Naropa, is among the many strengths of Tibetan culture. The more grindingly literal and prescriptive Xi Jinping gets, the more Tibetan float free and dance past his command to narrow the mind ever further. The Tibetan practitioners of dream yoga are one of the reasons Tibet has survived decade after decade of occupation and repression, of racist contempt at Tibet’s supposed backwardness.

Tellingly, the first audience this movie faced was China’s censors, empowered to make major cuts, or ban altogether. Instead it sailed through. The one and only change they required was to make it clear at what point on the road the wo/man and lobster depart Tibet and enter Yunnan. A tiny bit of bureaucratic formalism that exempts the censors from responsibility for the last part of the movie.

China’s inability to see Tibetans as they are, or to recognise their abilities, almost always results in painful directives. But it sailed past the censors, enabling skilled, imaginative movie makers to elude the dull, slogan filled minds of the censors, who see only “weirdness.” They were asleep at the wheel. When we think we are awake, and in command, we are asleep, compulsively driven by habit.

Dream yoga, as an advanced tantra requiring much prior mind training, is accessible to very few, so making it visually coherent is a creative achievement. Modern folk, the kind who go to film fests and seek out “arthouse” movies, are sometimes drawn to dream yoga for the wrong reasons, as validation of the truth of their dreams, a way of extending ego to encompass sleep. A practice to loosen the self becomes, in western Buddhism, a technology for solidifying the self. All the more reason to show -not tell- what happens when dreams and daily life mix, both being manifestations of what imprints into our storehouse.

Queena Li: “Another recurring line is: ‘When you lose your mind, come back. When I’m back, I’m here. And when I’m here, I’m out there.’ This is the line that I got from my other teacher. It was his way to help students practice searching their minds. It’s an exercise, that I really like, and I thought it would fit the film. It’s about losing oneself, but it’s also about coming back to one’s senses again. It’s a mantra that can remind oneself of coming back to the here-and-now, to the moment of presence, both of flesh and mind, time and place.

“I think that as a person and a creator, I try not to draw strict lines between the real world and the imaginative one. Limiting oneself to these two categories, real and unreal, is not my thing. When I was filming Bipolar, I wanted to film the dream as if it was reality. In that way, I made the line of fuzziness. I had to convince myself first, that the dreams are just as real. Only after that, I could convince the audience about the same. There’s a small exercise that I suggest you try if you can. It doesn’t have anything to do with the film, but it can be interesting. In the morning, when you’re awake, tell yourself that you’re dreaming. And when the evening comes, when you’re about to fall asleep, just tell yourself: “I’m waking up now, and going into the real life.”

This blog took a look in 2019 at the unfashionable topic of Chinese movies filmed in Tibet. Most assume a need to explain why a Han is in Tibet, and the reason, foundational to the unfolding movie, is often loss, such as the death of a lover. Bipolar also assumes loss is what drives the central character to Tibet.

But there the similarities end. Bipolar takes off down the road, bending all fixities, a wildly creative ride.

Xi Jinping’s China is off in a different direction, obsessed with pinning down and defining reality; editing out and suppressing everything that does not conform to the Thought of the only permitted thinker. We need more than ever to bend our categories, shake up the quotidian, loosen the mania for control. Bipolar does just that.