Blog four of five on an industry totally new to Tibet: mass manufacture of millions of alien trout in hydro dams on the Ma Chu/Yellow River

CONSUMING TROUT AND SALMON SHOWS YOU ARE CIVILISED

The mean price paid by consumers for salmon sold in Shanghai supermarkets in 2017 was RMB 176 per kilo, almost $26, a price comparable to what consumers in western countries are willing to pay.[1] There is a lot of money to be made.

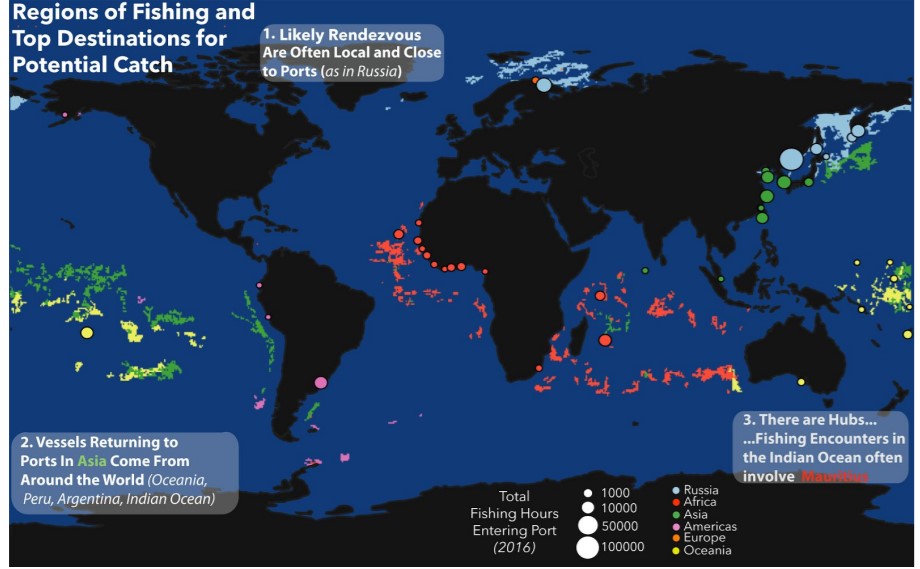

The wider context is that China is the biggest consumer and exporter of processed fish in the world, with a global fishing fleet extracting fish on an extraordinary scale worldwide. The US Department of Agriculture says: “China continued to be the world’s leading seafood producer in 2019, with production stable at 64.5 million metric tons (MMT). Aquaculture production was basically flat at 50.5 MMT, while wild catch fell to 14.0 MMT, a 5 percent decrease compared to 2018. E-commerce has become a popular way for Chinese consumers to purchase seafood products, leading some producers to shift their focus from foreign markets to domestic e-commerce channels.”[2]

Consumption of fish alien to China’s rivers, lakes and coastal waters is a sign of being an urban sophisticate, a discerning individual with cultivated tastes, a high-quality person others can look up to. Just about anyone in China can afford carp but eating salmon or rainbow trout demonstrates your superiority. Globally, only six per cent of fish eaten are salmon or trout.

China now produces around two million tonnes of fish from inland fish farms each year, which is 16 per cent of global inland fish production. This is an industry that worldwide is transitioning from small scale fish farming in farm ponds, to large scale industrial production. The transition from labour-intensive small scale to capital-intensive large scale is driven by the hunt for greater profit, which means concentrating on the highest priced fish, salmon and trout.

In 2015 wealthy Chinese in Beijing and Shanghai were surveyed to find out what they know about their virtue signalling consumption of the more expensive fish.[3] Most respondents showed little interest or concern about whether the fish they buy and consume are produced sustainably, or are in danger of extinction, often arguing that the high price consumers pay was the best protection against extinction.

The greater the industrialisation, and investment in cold chain commodity flows, the more premium priced fish, chilled, vacuum packed, standardised, barcoded, will be ready for export to the world. The UN Food and Agriculture Organisation forecasts that China’s fish exports, which were 8.17 million tonnes in 2018 will rise to 8.7 million tonnes by 2030. This could include trout manufactured in Tibet, on the plate not only in China’s cities but cities worldwide, if China succeeds in its plan to intensify trout production in the Amdo Ma Chu.

China’s long-term ambition is to export premium priced as well as cheaper fish, processed, packaged and chilled. In the shorter term, while China remains an importer of prestigious fish such as salmon and trout, the priority is to scale up production. This is where the deep inland factory farms of the Ma Chu come in. If China can, as planned greatly increase the scale, intensity and profitability of trout farming, the market is ready.

This is especially so if the trout marketers, with the backing of the Qinghai provincial government can continue to conflate trout with salmon, to get top price. If fish farming in the reservoirs impounding the Ma Chu could reach 150,000 tons of trout a year and manipulate their pale flesh colour to match pink salmon, Qinghai would have a substantial industry. What we see now could be just the start.

How would Tibetans feel about 20, 30, 50 million trout produced and sold from Tibetan waters, as against the current five million? On the scale planned, there are major impacts and ethical issues beyond those raised earlier. Those ethical issues are familiar to Chinese consumers, as there have been many scandals, during this century’s aquaculture production boom, over the health of the farmed fish, the health of the waters they grow in, and the health of the humans who eat them. The bad reputation of the coastal aquaculture industry is a major reason to move doing business so far from the coast is higher, given the expense of shipping the fish in oxygenated trucks to the processing plant in Fuqing and their forswearing illegal drugs, which lowers survival rates and increases the growth period of most fish to five years from three years.”

More recently, the main concern has been the addition of antibiotic tetracycline to fish feed in trout farms worldwide.[4] In a globalised industry all fish farms, whether big or small, wherever they are, are under pressure to use such short cuts to reducing fish deaths and increasing profits. If they don’t adopt similar methods, their prices are uncompetitive. This applies even to the 762 small scale trout farms in Himachal Pradesh, India, in Kullu, Chamba, Shimla, Kinnaur and Mandi districts.[5]

A 2020 comprehensive guide to taking care of welfare of farmed trout is freely downloadable. This welfare manual, written by Norwegians, suggests a dawning awareness that fish are fellow sentient beings: “Many studies have shown that fish have a qualitative experience of the world, have a good ability to learn and remember, have anticipations of the future, have a sense of time, can associate time and place, can make mental maps of their surroundings, can know their group members and can cooperate with them. Fish can also learn by observing others, and some fish can even make innovations and use tools.”

What is fed to caged trout has many consequences. If the premanufactured feed is too low in nutrients, the fish don’t grow as fast as on competing fish farms, slowing production and reducing profit. If, however, the feed is too rich in nutrients, those nutrients build up in the water, feeding other organisms, changing the whole ecosystem. This is problematic in trout farms worldwide.[6] Scientists from the Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency calculate that in 2010 1.2 million tons of nitrogen entered fish farm waters worldwide, in excess of what was eaten by the farmed fish.[7] They forecast this figure is likely to rise, even though fish farmers do try to not overfeed.

IS THERE A DISTINCTIVELY TIBETAN RESPONSE?

Integrating Tibetan waters into a competitive global industry means these are all questions Tibetans, for the first time, need to consider. In a time of climate change, global industries have global impacts, and have to adapt to global challenges. Again, Tibetans never had to worry about such matters, back in the day, not so long ago, when all Tibetans “lived worlds where economic, social, and sacred ties were not separated. In Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist, economist Kate Raworth calls for the need to recreate or re-recognize ties between economic activities and complex social, biological, and cultural systems. Such re-integration, she argues, is the foundation of a necessary shift from extractive to regenerative systems. She writes: ‘When political economy was split up into political philosophy and economic science in the late nineteenth century, it opened up a “moral vacancy” at the heart of public policymaking. Today economists and politicians debate with confident ease in the name of economic efficiency, productivity and growth—as if those values were self-explanatory—while hesitating to speak of justice, fairness and rights.’”[8]

Tibetans do seek to be heard on justice, fairness and rights. Displaced Tibetans may find it hard to scientifically measure antibiotic and effluent nutrient pollution in the Ma Chu trout farms. But Tibetans can recall the strengths of traditional Tibetan culture, which did not separate the lived world into separate realms of the economic and the sacred. To remember this is to discover a basis for questioning not only intensive trout farming but all of China’s campaigns to intensify production in Tibet.

The more trout farming is globalised, the more complex it gets, and harder to change in a good direction. China calls this development, as if such intensification, acceleration and productivism is automatically good, unquestionably beneficial.

China, the world’s aquaculture superpower, having encouraged fish farm intensification for decades, now struggles with the consequences. Pollution of soil and water by antibiotics fed to fish (and to feedlot farmed animals) is now so pervasive in eastern China, the scientists of the Key Laboratory of Environment and Population Health, National Institute of Environmental Health, Chinese Centre for Diseases Control and Prevention, and Key Laboratory of Land Surface Pattern and Simulation, Institute of Geographical Sciences and Natural Resources Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences, and are alarmed.[9] They say: “China is facing serious antibiotic pollution in the environment, and it is becoming a significant threat to ecology and human health. The consumption of antibiotics in 2013 was approximately 162,000 tons, with 48% being used for humans and the rest for animals. This was 150 times more than the UK and 9 times more than the USA. Among the total consumption, more than 50,000 tons were emitted into water and soil environments.”

One Chinese answer is to relocate fish farming, away from polluted eastern China, far inland, to Tibet, starting again in landscapes Chinese consumers perceive to be pure and unpolluted. Fish farming along China’s coasts is a huge industry. Satellite remote sensing data monitoring concludes “China’s 2018 coastal zone raft aquaculture area comprised 194,110 ha, the cage aquaculture area covered 57,847,799 square meters.”[10] If only part of this was transferred to Tibet, for a fresh start, the burden would be great.

A major ethical concern is what to feed to caged fish to maximise growth to a size suited to slaughter, which in industrial fish farming is usually electrocution followed by bleeding each trout to death.

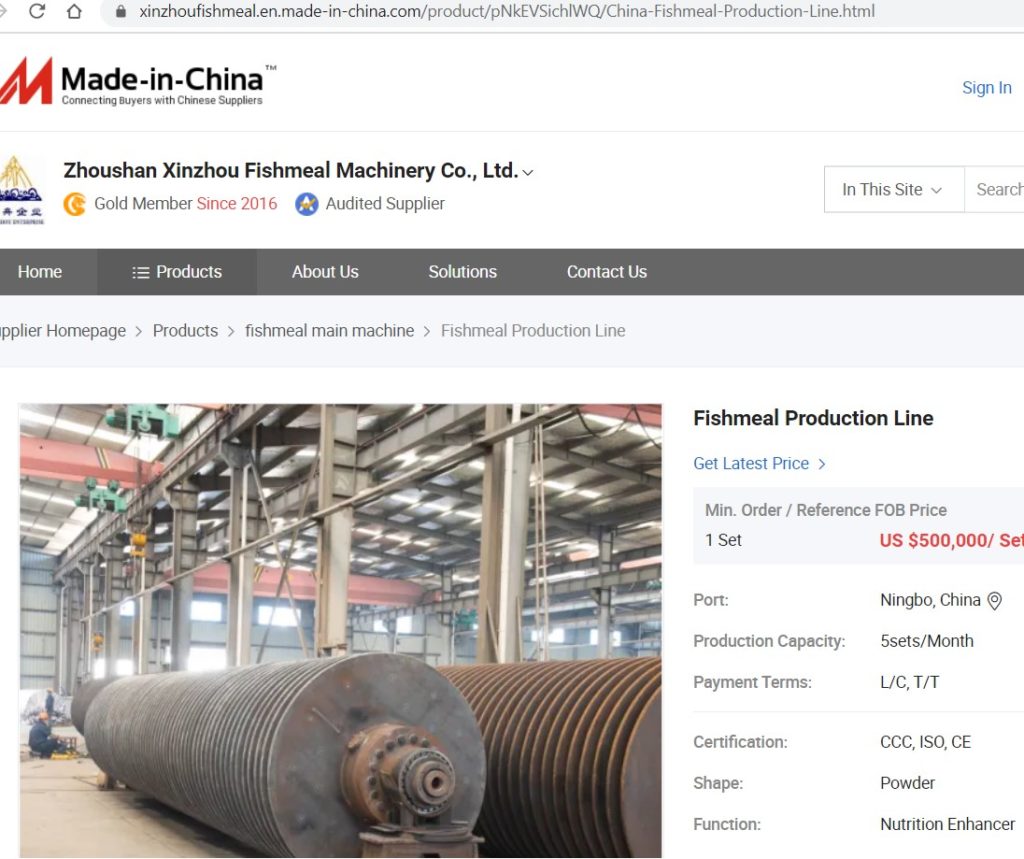

Manufacturing pelletised dry feed for trout is a substantial industry, also globalised. For each kilo of weight gain in each fish, two kilos of feed pellets must be thrown into the water. Since those feed pellets are highly nutritious, with a very high proportion of protein, they could feed people directly. This is one of the biggest objections to fish farming: it is a highly inefficient use of scarce food. Further, the standard formula, in order to achieve a high level of protein and fish oil, includes a lot of cheaper fish that have been caught en masse, killed, dried, ground up and pelletised. This means the wastes from killing the previous generation of rainbow trout -guts, bones, scales- are routinely gathered to feed the next generation, in addition to the inclusion of wild fish that get caught in fishermen’s nets but only attract low prices.

This barbaric, almost cannibalistic practice has long been routine, but global overfishing has become so widespread there is now a shortage of cheap fish in the oceans, and the industry is actively seeking vegetable based alternative pellet manufacture.

FISH EATING AS SHOCKING

Tibetan horror at consuming fish shows up in Tibetan art, illustrating the life of the Indian Buddhist adept Luipa རྒྱ་གར་གྱི་གྲུབ་ཆེན།. Paintings of siddha Luipa usually show him eating the most revolting of foods: fish guts. This deliberately transgressive image is a visual reminder that if you are serious about fully awakening, there is no normal or abnormal, no convention, no boundary. Luipa is still revered in Tibet, 13 centuries after his life in India, for discovering -the hard way- that the inner path is no respecter of social norms. Luipa ‘s liminal, antinomian, playful story admonishes us all to see past what we consider normal: “As a young king on the island of Shri Lanka, Luipa felt only contempt for his wealth and power. He made one attempt to escape the royal palace but was stopped by his brothers who bound him in golden chains. On his second attempt he succeeded in bribing his guards, then disguising himself in rags he fled for the country of Rameshvaram. He became a simple yogin, sleeping on a bed of ashes and eating only what was given to him in his begging bowl. Despite his meagre conditions, he remained handsome and charming. When his travels brought him to Pataliputra he met a courtesan outside a house of pleasure who was an incarnate worldly Dakini. She told him that although he was quite spiritually advanced and pure, there was still a pea-sized obscuration of royal pride in his heart. She then poured some putrid rotten food into his begging bowl. When he thought she was gone, he threw the contents of the bowl into the gutter. The Dakini, who had secretly been watching him, appeared and scorned him. She stated that someone who truly wished to attain enlightenment would not be concerned with the purity of their food. Luipa was mortified and realized that his judgmental mind was still active and that he still viewed certain things as intrinsically more desirable than others, and that this was an obstacle on the path toward enlightenment. He decided his new meditation practice would be to live on the banks of the Ganges River and eat nothing but the entrails of fish that were left by local fisherman. He did this for twelve years and then achieved a level of realization, transforming the fish entrails into the nectar of pure awareness through the insight that that the nature of all things is emptiness. Luipa lived the rest of his days as a respected and revered teacher.”

[1] Ya Du, Xiaobo Lou, Taro Oishi, Yiyang Liu, The influence of quality characteristics of aquatic products on its price determination in China-A case of salmon products in supermarkets of Shanghai, Aquaculture & Fisheries journal, article in press 2020

[2] USDA FAS GAIN report, China: Continued Seafood Import Growth in 2019, May 08,2020, Report Number: CH2020-0058, https://www.fas.usda.gov/data/china-continued-seafood-import-growth-2019

[3] Michael Fabinyi et al., Aquatic product consumption patterns and perceptions among the Chinese middle class, Regional Studies in Marine Science 7 (2016) 1–9

[4] Murat Topal, Investigation and monitoring of tetracycline and degradation products in waters of trout farm, Pamukkale University Journal of Engineering Sciences, 23(3), 273-278, 2017

[5] Bhartiya Krishi Anushandhan Patrika, 33(4): 58-61, 2019

[6] M. A. B. Moraes et al., Environmental indicators in effluent assessment of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) reared in raceway system through phosphorus and nitrogen, Brazilian Journal of Biology, 2016, vol. 76, no. 4, pp. 1021-1028

[7] A. F. Bouwman et al., Hindcasts and Future Projections of Global Inland and Coastal Nitrogen and Phosphorus Loads Due to Finfish Aquaculture, Reviews in Fisheries Science, Volume 21, 2013 – Issue 2

[8] Wendi L. Adamek, As if This Is Home, Canadian Journal of Buddhist Studies, Number 15, 2020. https://thecjbs.org/archive-document-details/?id=231

[9] Jia Lyu et al., Antibiotics in soil and water in China: a systematic review and source analysis, Environmental Pollution, 266 (2020) 115147

[10] Yueming Liu et al., Satellite-based monitoring and statistics for raft and cage aquaculture in China’s offshore waters, International Journal of Applied Earth Observation & Geoinformation, Volume 91, September 2020, 102118