KOKOSHILI/HOH XIL:

TIBET’S EMPTY QUARTER OR HUMAN LANDSCAPE?

NATURAL AND CULTURAL WORLD HERITAGE

Blog 2 of 2 on the decision facing UNESCO World Heritage Committee in the first week of July 2017

The inspiring example of Tibetans determined to protect wildlife as fellow sentient beings created a worldwide movement to stop animal slaughter. It is that Tibetan campaign to save the tsö antelopes that China now wants us to forget, denying even that Kokoshili is a human landscape. China demands amnesia about the brave Tibetans who 25 years ago halted the massacre, insisting that Kokoshili is a “no-man’s land” with no human presence, a wildlife wilderness untouched by human hand, awaiting discovery by today’s railway tourists.

Fortunately, despite official amnesia, there is a rich record of how Tibetans led a campaign to save the antelopes, and inspired a global civil society movement, with almost no government involvement.

We are also fortunate that this popular movement inspired ordinary Chinese people, resulting in rich documentation, telling the story of the Tibetan Wild Yak Brigade of wildlife rangers, from a Tibetan viewpoint. Two Chinese storytellers, movie director Lu Chuan and journalist Liu Jianqiang both moved fully into seeing the world, including Kokoshili, through Tibetan eyes, and gave us deeply moving accounts, from a Tibetan viewpoint.

Lu Chuan’s movie Kekexili: Mountain patrol came out in 2004, the same year a Chinese government publisher put out a deeply sympathetic photojournalism book by wildlife photographer Xi Zhinong.[1] Liu Jianqiiang’s story of the Tibetan wildlife rangers was published in Chinese in 2010 and in English in 2015. Through them, we can know so much about a China that was able to deeply connect and respect Tibetans. This blog draws on those insider narratives.

A POPULAR WORLD WIDE TIBETAN-LED MASS MOVEMENT SAVED THE ANTELOPES FROM EXTINCTION

In the early 1990s it was official policy to encourage even remote areas to take whatever opportunity there might be to get rich, to set up small enterprises based on local strengths; and a Western Working Commission was announced, for the development of Kokoshili. The Tibetans determined to risk their lives protecting the antelopes saw a slim chance, and took it. In 1993 they became the Western Working Commission, a job no-one else wanted, headed by local Communist Party secretary Sonam Dargye.

He was ahead of his time. Today we do talk of markets and payments for environmental services, but not then. Officially the Western Working Commission was to somehow bring development to Kokoshili. Party secretary Sonam Dargye, one of the first generation of Tibetans with a modern education, was keen on development. But first the resources of Kokoshili being plundered had to be protected, and an Office of Wildlife Protection became part of the work of the Western Working Commission. For the first time, Tibetans had legal authority to arrest poachers and hand them over to police, but almost no budget, and a contract with Drito county providing minimal funding for just one year, after which they were on their own.

That was a slender legal basis to deal with 30,000 gold feverish immigrants, armed and used to slaughter. Yet ranger Sonam Dargye and his Tibetan colleagues did stop the massacre, and became national heroes, known across China for their courage in standing up to violence. Chinese photographers, journalists and film makers came to document their efforts, sparking a popular movement. Chinese and international environmental NGOs became involved.

On the ground, the long and dangerous patrols of the Wild Yak Brigade, as they called themselves, succeeded in slowing the slaughter of the antelopes, and capturing the popular imagination. All over China, people wanted to help them succeed. In distant Tianjin, on the coast beyond Beijing, a TV station held a telethon  fund raiser to buy jeeps and fuel for the Wild Yak Brigade. Dancers in costume inspired by antelopes staged dance performances.

fund raiser to buy jeeps and fuel for the Wild Yak Brigade. Dancers in costume inspired by antelopes staged dance performances.

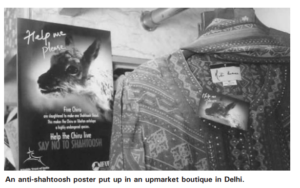

Global NGOs campaigned to stop the shahtoosh shawl trade based on the massacre of Tibetan antelopes.

These successes were an embarrassment to China’s government, a shameful admission that the rule of law, of a sovereign state, did not reach the badlands. Until the Wild Yak Brigade Kokoshili was a lawless frontier.

The more widely ordinary Chinese people celebrated the heroism of the Wild Yak Brigade, the more the state lost face. In 2001, the Brigade was abruptly terminated, its powers transferred to the Administration Bureau of the Hoh Xil Nature Reserve, which on paper was created in 1995, the bureaucratic source of the current World Heritage nomination. By then Sonam Dargye was seven years dead, shot by a poacher. Other Tibetans stepped in to persist with the dangerous frontier work.

By the time the Wild Yak Brigade/Western Working Commission was abolished, urban China had been mobilised in support, a conference on trade in endangered species had been held, movie maker Le Chuan was making his re-enactment of the rangers’exploits, which became the 2004 hit movie Kekexili: Mountain Patrol. [2]

Wildlife conservationists worldwide took up the cause. In India, in order to outlaw the luxury shahtoosh shawl industry, Wildlife Trust of India first proved Tibetan antelopes also live in Ladakh, in India’s far north, making it an Indian animal entitled to legal protection. Celebrities were mobilised to post videos calling on their followers to refrain from buying shahtoosh shawls.

The decline in the number of antelopes slaughtered was achieved not by governments, treaties and formal ascription of World Heritage status; but by a global mobilisation of civil society, uniting Tibetan rangers on the frontline with European celebs warning that shahtoosh shawls, once cool, are now toxic. It was this ad hoc coalition of NGOs, wildlife campaigners and frontline Tibetan rangers that made shahtoosh the shawl of shame, and halted the extinction of the tsö antelopes. The turning point was the 1999 gathering of all parties, in the Qinghai capital, Xining. The resulting Xining Declaration insists on local community involvement in all future antelope protection programs.[3] By 2016 the Tibetan antelope was taken off the IUCN Red List of endangered species, though it is still listed as near threatened. Community based conservation, connecting high end fashionistas and Tibetan badlands rangers, had saved the tsö from extinction.[4]

Chinese and Tibetans had joined in partnership, and the slaughter came to almost a complete end. In 2010 Liu Jianqiang published in Chinese a booklength insider account of the heroism of the rangers, with an English translation in 2015. [5] The full story is available to all. It is full of the voices of the Tibetans of this “no-man’s land”, passionately debating how best to protect it.

Since then, the state has taken over. On paper it is committed not only to rebuilding the Tibetan antelope herd, but to protecting the entire habitat, and the many other endemic species, including snow leopards, brown bears and wild yaks. The state alone is in charge. This does not mean, however, the state has coherent or consistent policies for achieving its goals of human poverty alleviation for Tibetan nomads, and effective conservation of endangered species. In fact, in much of the antelope habitat, China persists in requiring nomads to construct fences, which interrupt antelope migrations.[6]

How is the state doing? Tibetan antelope numbers continue to gradually recover. The tsö continue to be very wary of crossing the QTEC engineering corridor, which they must, in order to reach their safe birthing grounds. Chinese scientists in 2011 reported: “Tibetan antelopes exhibited risk-avoidance behaviour towards roads that varied with proximity and traffic levels, which is consistent with the risk-disturbance hypothesis.” The trains headed for Lhasa seldom stop at any of the 13 scenic viewing platforms erected along the rail traverse of Kokoshili, because the antelopes, the iconic sight to be photographed, flee approaching trains.[7]

How is the state doing? Tibetan antelope numbers continue to gradually recover. The tsö continue to be very wary of crossing the QTEC engineering corridor, which they must, in order to reach their safe birthing grounds. Chinese scientists in 2011 reported: “Tibetan antelopes exhibited risk-avoidance behaviour towards roads that varied with proximity and traffic levels, which is consistent with the risk-disturbance hypothesis.” The trains headed for Lhasa seldom stop at any of the 13 scenic viewing platforms erected along the rail traverse of Kokoshili, because the antelopes, the iconic sight to be photographed, flee approaching trains.[7]

A LONG TERM FUTURE FOR KOKOSHILI

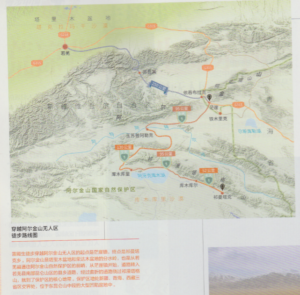

Antelope habitat is much more than the area designated by China for World Heritage. China’s focus is almost entirely on just one species, the antelope, rather than on habitats, ecosystems and whole landscapes.

A holistic approach is needed, rather than publicising a single iconic species, used by China as a symbol of its 2008 Olympics in Beijing, as the sole attraction. A comprehensive approach would give local Tibetan communities, both within the designated World Heritage area, and in their traditional nomadic wintering grounds to the east, ongoing roles as stakeholders. These nomads have for thousands of years taken their herds into Kokoshili for summer pasture, moving alongside the antelopes and gazelles. The Tibetans have proven, by taking the lead in conservation in the 1990s, that they are part of any long term solution, not part of the problem. Yet China persists in labelling them problematic, removing many to Gormo, to live in the shadow of petrochemical factories.

Much of the proposed World Heritage area is the uppermost reaches of two great rivers, the Yangtze and the Mekong, which makes whole landscape protection essential for hundreds of millions of people downriver. The rest of Kokoshili does not drain to rivers, but is a land of lakes, on a flat plain, collecting but not releasing inflows of water, which freezes over in winter and melts in summer, creating water meadows that can be navigated by animals, but badly bogs jeeps, a major reason China calls it “no-man’s land.” Due to climate change, recent data shows an increase in summer rain, increase in grasses for both antelopes and nomad herders, and increase in the area of lakes.[8] This is one of the few places where global climate change, at least in the short-term, has beneficial effects. Kokoshili is rapidly recovering, after decades of rapacious mining, and antelope slaughter. There is summer grass for both wild and domestic animals, if managed skilfully by those who know the land, as Tibetans do. In the past human use and wildlife existed together, in future this could expand.

DOES UNESCO WORLD HERITAGE STATUS IN TIBET RESULT IN EFFECTIVE PROTECTION?

World Heritage status transforms areas inscribed, not always for the better. UNESCO’s World Heritage Committee need only look at the record of its earlier acceptances of China’s nominations of natural landscapes in the Tibetan Plateau. In 1992 the spectacularly beautiful Jiuzhaigou valley, in Sichuan, directly north of Chengdu, became World Heritage, its inscription partly as panda conservation habitat. No panda has been seen there for 20 years. This valley, named for its nine Tibetan fenced villages, has been surrounded by luxury resorts, millionaire villas, conference centres and a high-speed railway is under construction. The resort operators on their website proudly proclaim it the eastern Davos. Meanwhile, under a deluge of tens of millions of domestic Chinese tourists, UNESCO has increasingly worried that the values for which it was accepted are seriously threatened. But the response has been to make the Tibetan villagers, who cared for this land for millennia, to limit their land use, by forbidding farming, then forbidding them to earn a little by offering homestays to a few of the tourists. Both of these restrictions were proposed by IUCN missions sent by UNESCO to find solutions to the extreme over-use of the Jiuzhaigou valley by China’s tourism accommodation industry.

In 2002 the World Heritage Committee accepted China’s nomination of a bigger area, customary home of Tibetans and other minority nationalities nearby, as the Three Parallel Rivers site of Yunnan province. Three of the world’s great rivers –the Yangtze, Mekong and Salween- flow there in parallel, only 20kms apart, separated by high ridges, which are rich grasslands, ideal for dairy and livestock production. None of the actual rivers, after which the site is named, are actually inside the World Heritage boundaries, which were carefully mapped by China to exclude the riverbeds, so as to allow for the construction of hydro dams and power grids to carry the electricity generated there far away to China’s coastal factories. The dams and power grids are now under construction, and the World heritage Committee, despite protests, has been firmly told by China to mind its own business, as the dams, mines and grids are outside the World Heritage area, in the steep valleys below.

CHINA’S AGENDA

Far from proposing an inclusive World Heritage property that embraces nature and culture, conservers and conserved, human protectors and endangered species together, China’s nomination comes from the Ministry of Housing, Urban and Rural Development (MHURD). As urbanisation is at the core of China’s development model, this is a powerful ministry, but what has a housing department got to do with wildlife in a remote “no-man’s land”?

The answer is that MHURD runs zoos in urban areas.

It also has some responsibility for scenic spots, and the 13 bare railway platforms on the rail line to Lhasa, as it traverses Kokoshili, are classified as scenic spots, designated by the state as vantage points from which to take the iconic photos which qualify the photographer as an individual, with educated tastes and personal accomplishments, a consumer of the wild with proof of having been there.

China’s most recent report to the UN Convention on Biodiversity states: “Scenic spots are important areas for biodiversity conservation. Since 2002, MHURD has established a system of information for monitoring and managing national-level scenic spots, using remote-sensing and GIS technologies to monitor natural resources conservation and implementation of relevant plans in scenic spots.”[9]

How can MHURD make those windswept platforms to nowhere into scenic spots where antelopes are photogenically available? Only by impeding the migratory flow of herds of female antelopes seeking their birthing grounds, fencing them in to be available to the camera. In short, a zoo.

WAYS AHEAD

After twice finding itself powerless to limit the impacts of rapid urbanisation and industrialisation, in two key World Heritage natural landscapes of the Tibetan Plateau, Tibetans now hope UNESCO has learned from experience that China uses World Heritage listing directly as a brand equity boost to promote mass tourism, while also arguing vigorously that it is China’s business alone if it also industrialises World Heritage landscapes with dams, grids and resorts.

What is the lesson to be learned? World Heritage status can be a blessing, ensuring effective protection of landscapes, habitats and local human livelihoods. The problem is in defining Kokoshili, like Jiuzhaigou and Three Parallel Rivers, from the outset, purely as natural landscapes, omitting the human cultures that in all three areas have protected lands and animals, wildlife and domestic herds, sustainably for thousands of years.

The alternative facing the World Heritage Committee is to make Kokoshili a landscape protected as both natural and cultural. There is plenty of precedent for this, in China and elsewhere. The mountains sacred to China’s Buddhists are World Heritage sites classified as both natural and cultural hybrids. In order to qualify as cultural heritage, monumental buildings are not necessary, as director of the World Heritage Centre, Dr Mechtild Rössler pointed out in 2016: “The inclusion of such landscapes on the World Heritage List is justifiable by virtue of the powerful religious, artistic or cultural associations of the natural element rather than material cultural evidence, which may be insignificant or even absent. This type is exemplified by Uluru Kata Tjuta in Australia, Sukur in Nigeria and Tongariro National Park in New Zealand.”[10]

[1] Tracking Down Tibetan Antelopes, Foreign Languages Press, Beijing, 2004

[2] Lu Chuan’s hit 2004 movie Kekexili http://www.dailymotion.com/video/xse8pd_kekexili-mountain-patrol-eng-subtitles-1-of-9_travel in nine online episodes

[3] International Declaration for the Conservation of and Control of Trade in the Tibetan Antelope, TRAFFIC Bulletin Vol. 18 No. 2 (2000) http://www.traffic.org/bulletin-download

[4][4] http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/15967/0

[5] Liu Jianqiang, Tianzhu, Xizang Renmin Chubanshe, Lhasa, 2010

Liu Jianqiang, Tibetan Environmentalists in in China, Lexington, 2015

[6] Joseph L. F o x , Kelsang Dhondup and Tsechoe Dorji, Tibetan antelope Pantholops hodgsonii conservation and new rangeland management policies in the western Chang Tang Nature Reserve, Tibet: is fencing creating an impasse? Oryx, 2009, 43 #2, 183-190

[7] Lin Xia, Qisen Yang, Zengchao Li, Yonghua Wu, Zuojian Feng, The effect of the Qinghai-Tibet railway on the migration of Tibetan antelope Pantholops hodgsonii in Hoh-xil National Nature Reserve, China,Oryx / Volume 41 / Issue 3 / July 2007

[8] Zhao Qian, Wu Weiwei, Wu Yunl ong, Variations in China’s terrestrial water storage over the past decade using GRACE data, Geodesy and Geodynamics 2 0 1 5 , v o l 6 no 3 , 1 8 7-1 9 3

ong, Variations in China’s terrestrial water storage over the past decade using GRACE data, Geodesy and Geodynamics 2 0 1 5 , v o l 6 no 3 , 1 8 7-1 9 3

[9]China’s Fifth National Report on the Implementation of the Convention on Biological Diversity,The Ministry of Environmental Protection of China March, 2014 https://www.cbd.int/doc/world/cn/cn-nr-05-en.pdf p 65

[10] Dr Mechtild Rössler World Heritage cultural landscapes: A UNESCO flagship programme 1992 – 2006, Landscape Research, 31:4, 333-353