EVALUATING CHINA’S NOMINATION OF HOH XIL NATURE RESERVE TO BECOME A UNESCO WORLD HERITAGE NATURAL PROPERTY

#3 of a series of 3 blogs

WATER VERSUS PASTORALISM

In 2007, China’s leading research institute for making Tibet a scientific object reported that: “No man’s land records of scientific investigation in China for the first time the work of the Tibetan Plateau memoirs, ‘broke into the roof of the world Qiangtang no man’s land,’ a book has been finalized, is being organized by the Academy Press, publishing and printing. In 2007, the expedition team traversed from the north into southern Xinjiang Kunlun Mountains Ruoqiang, through no man’s land of northern Tibet, near Tibet Highway……” (China’s Qinghai-Tibet Plateau Research Work Summary 2007, China’s Qinghai-Tibet Plateau Research 2007 annual summary Itpcas.cas.cn)

China’s insistence that much of Tibet is “no-man’s land is deeply rooted.

As China’s north-south highway and railway across the Hoh Xil “no-man’s land” intersect at several places with the west-east uppermost source of the Yangtze, China has already intruded on the most pristine river sources it represents as the guarantor of water purity downriver. The paradox is that mass transit access bisecting a fragile landscape now provides the basis for mass tourist access, while China persists in portraying the entire Hoh Xil as pure “no-man’s land”,  a wilderness untouched by human hand. To say the least there is a tension between a multimodal engineering corridor bisecting the sources of the Yangtze; and the image China wishes to project, of primal purity.

a wilderness untouched by human hand. To say the least there is a tension between a multimodal engineering corridor bisecting the sources of the Yangtze; and the image China wishes to project, of primal purity.

The tragedy of the present moment is that China’s way of dealing with that tension seems to be to let tourists in, while shutting Tibetan pastoralists out. The pastoralists of the Hoh Xil are depicted as environmental vandals, despoiling the sprawling plateau lands between the glaciers and the thirsty Chinese lowlands.

China’s developmentalist ideology accuses customary land users, the pastoralists, of being both unproductive and unsustainable, hence the need for a “no-man’s land” that can then become Chinese, and filled with tourists. As the eminent Mongol scholar Uradyn Bulag points out: “In recent years, environmental degradation of the Inner Asian steppeland was powerfully symbolised by the sandstorms that swept across Mongolia, Inner Mongolia and northwestern China, the dust reaching as far as Texas, the United States. The environmental catastrophe was brought about by the developmentalist logic, which destroyed the ecological habitats, inducing a reverse human flow, indigenous minorities being evicted from their pastures, which have been closed to create a ‘no-man’s land’, for ecological recovery.” (Uradyn E. Bulag, Hybridity and Nomadology in Inner Asia, Inner Asia, Vol. 6, No. 1 (2004), pp. 1-4

China justifies this contradictory attitude by blaming mobile pastoralists and their herds for land degradation, which threatens watersheds, and Tibet’s reputation, in China’s eyes, as “China’s Number One Water Tower.”

At the same time, China invokes planetary climate change as an objective reason for removing the pastoralists, relocated to demoralised, useless existences on urban fringes. China claims climate change as force majeure, necessitating exclosure of pastoralists from their pastures, because a warming climate is causing desertification, especially in the drylands of Hoh Xil and Changtang.

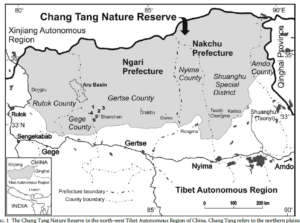

However, the scientific evidence, both from Chinese and global scientists, in report after report, is that in Tibet, including the proposed World Heritage area, rainfall is increasing, river flows are increasing, both due to increased precipitation and glacier melt; and for the first time in thousands of years, lake levels are rising. As both Hoh Xil and Changtang are lake lands, with many of the lakes having inlet streams but no outlets, this is a significant change, suggestive of a return to the conditions when Tibetans first made the Changtang their Zhang Zhung homeland. If anything, the long term trend is conducive to a greater human presence, not less.

A team from China’s leading cold regions research institute, the Academy of Sciences Cold and Arid Regions Environmental and Engineering Research Institute, recently measured the size of all 83 of the Hoh Xil’s largest lakes, and found that: “From the 1970s to 2011, the lakes in the Hoh Xil region firstly shrank and then expanded. In particular, the area of lakes generally decreased during the 1970s–1990s. Then the lakes expanded from the 1990s to 2000 and the area was slightly higher than that in the 1970s. The area of lakes dramatically increased after 2000. From 2000 to 2011, the lakes with different area ranks in the Hoh Xil region showed an overall expansion trend. Some lakes were merged together or overflowed due to their rapid expansion. The increase in precipitation was the dominant factor resulting in the expansion of lakes in the Hoh Xil region. The secondary factor was the increase in meltwater from glaciers and frozen soil due to climate warming.”[1]

China’s discourse on degradation emphasises overgrazing by pastoralists (who are constrained by compulsory fencing and fixed land tenure allocations that restrict mobility) and is silent on other causes of degradation. The waves of gold rushes into arid areas of Tibet, ripping river banks, dredging river courses, chopping shrubbery for fuel, diverting river streams, leaving toxic mercury and cyanide in streambeds, are nowhere mentioned in China’s proposal to UNESCO as a source of degradation, and reasons why Hoh Xil is far from pristine, due to recent, uncontrolled greed. A section outlining the history of mining in Hoh Xil and Changtang, above, illustrates this more exactly.

UNESCO must be absolutely sure this proposed World Heritage area is not gravely compromised by China’s plans to divert water, on a massive scale, from upper tributaries of the Yangtze via tunnels through the mountains, at least 100 kms long, to upper tributaries of the Yellow River. China’s published plans for this massive water diversion indicate locations for dams and tunnels very close to the proposed World Heritage property, or perhaps within it. UESCO has already experienced the extreme frustration of having allowed China to define the boundaries of the Three Parallel Rivers World Heritage property, far downriver on the Yangtze, to exclude the rivers themselves, thus allowing China to construct dams. In vain, UNESCO has protested, only to be told that UNESCO has no jurisdiction or right to question the dam builder.

BUFFERING THE WILDERNESS

The ultimate source of the Yangtze (Dri Chu in Tibetan), long veiled in myth, in modernity plays a key role in the romanticisation of the pristine, the pure, authentic, wilderness source, high in the glaciers, which are the guarantors of purity for all downstream. The source is a place for intrepid expeditioners, commemorative plaques, videos and songs, not the main highway carrying everything China manufactures, from soy sauce to surveillance equipment, into central Tibet. Making Hoh Xil World heritage will solve this dilemma, making a virtue of a contradiction. Once it becomes a prized destination, it will be yet another example of how the people’s government enables the masses access to the most special sites, for a photo opportunity to be shown to the folks at home, proof that you are a civilised person who has done the circuit of iconic scenic sites.

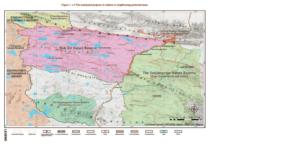

Thus it is that the bureaucratic distinction between the three huge nature reserves of the Tibetan Plateau is now dissolving. Of the 77,000 km2 China is now nominating for acceptance by UNESCO, 41.5 per cent by area is in the Sanjiangyuan nature reserve, henceforth to be included in Hoh Xil.

Technically, this added area is not core but buffer, but when one looks at China’s legislation defining these exclusionary categories, one finds the definition of buffer to be highly exclusionary. The nature reserve regulations are clearly aimed at protecting that which is most precious, beautiful and exceptional.[2] The regulations state: “Article 18. Nature reserves may be divided into three parts: the core zone, buffer zone and experimental zone. The intact natural ecological systems and the areas where precious rare and vanishing wildlife species are concentrated within nature reserves shall be delimited as the core zone into which no units or individuals are allowed to enter. No scientific research activities are allowed in this zone except for those approved according to Article 27 of these Regulations. Certain amount of area surrounding the core zone may be designated as the buffer zone, where only scientific research and observation are allowed. The area surrounding the buffer zone may be designated as the experimental zone, where activities such as scientific experiment, educational practice, visit, tourism and the domestication and breeding of precious, rare and vanishing wildlife species may be carried out.”[3]

This leaves a huge area that will remain Sanjiangyuan, the main area where pastoralists are being rapidly removed, required to lead unproductive sedentary lives in peri-urban concrete cantonments.

This leaves a huge area that will remain Sanjiangyuan, the main area where pastoralists are being rapidly removed, required to lead unproductive sedentary lives in peri-urban concrete cantonments.

The addition of 32,000 km2 of Sanjiangyuan to the Hoh Xil, constituting the package now before UNESCO, adds iconic river sources into the mix, which matters a lot to China. In 2015 China floated the idea of making the sources of the three rivers for which the Sanjiangyuan is named –the Yellow, Yangtze and Mekong- into national parks.[4] The Qinghai provincial forestry bureau explained that: “The park will cover more than 30,000 square kilometres, including the rivers’ sources in Madoi, Zhidoi and Zadoi counties. If the plan is given the green light, construction can begin as early as the end of this year.” These are pinyin Chinese names for Mato, Drito and Dzato, in Tibetan, names that mean, in turn, the source of the Yellow, source of the Yangtze and source of the Mekong. It is this proposal that has now been upgraded to a World Heritage nomination, with support at the highest level of the party-state.

HUMAN RIGHTS

Establishing a World Heritage property solely for wildlife conservation, mass safari tourism and infrastructure engineering corridors is a violation of the human rights of the Tibetan population who will be displaced, demobilised and excluded, in the name of conservation.

A recent survey of similar cases states: “there now exists a very detailed and situation-specific set of internationally agreed rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities that should be fully considered by actors involved in conservation initiatives. Distilling this large body of international law to identify key standards that should be upheld in all conservation settings is of utmost importance if conservation actors are to play their part in respecting human rights in the areas in which they work.

“Over 30 non-exhaustive and non-exclusive categories of rights can be identified which

can be affected by conservation interventions including:

Substantive Individual and Collective Rights

- Overarching human rights;

- Women;

- Children;

- Indigenous Peoples (collective rights);

- Traditional governance systems and customary laws;

- Cultural, spiritual and religious integrity;

- Assimilation;

- Cultural traditions;

- Cultural expressions;

- Knowledge, innovations and practices;

- Education and languages;

- Development;

- Cultural and natural heritage.

Substantive land, and natural resource rights

- Lands and Territories;

- Stewardship, governance, management, and use of territories, lands and natural

resources;

- Customary use;

- Sustainable use;

- Equitable conservation of biodiversity;

- Protected areas;

- Sacred natural sites;

- Food and agriculture;

- Water;

- Climate change;

- Forests;

- Deserts.

Procedural Rights

- Benefit sharing;

- Precautionary approach;

- Free, prior and informed consent;

- Cultural, environmental and social impact assessments;

- Information, decision making and access to justice; and

- Capacity building and awareness.”[5]

All 30 rights listed apply to China’s nomination of Hoh Xil, which cannot proceed unless fully addressed. The specific UN conventions violated if Tibetans of Hoh Xil/Sanjiangyuan are silenced, ignored and disempowered are listed specifically:

“Indigenous Peoples have the right to manifest, practise, develop and teach their spiritual and religious traditions, customs and ceremonies; the right to maintain, protect, and have access in privacy to their religious and cultural sites; the right to the use and control of their ceremonial objects; and the right to the repatriation of their human remains. (UNDRIP).

Indigenous Peoples have the right to maintain and strengthen their distinctive spiritual relationship with their traditionally owned or otherwise occupied and used lands, territories, waters and coastal seas and other resources and to uphold their responsibilities to future generations in this regard (UNDRIP).

Indigenous Peoples have the right to promote, develop and maintain their institutional structures and their distinctive customs, spirituality, traditions, procedures, practices and, in the cases where they exist, juridical systems or customs, in accordance with international human rights standards (UNDRIP).

In applying the provisions of this Part of the ILO Convention No. 169 governments shall respect the special importance for the cultures and spiritual values of the peoples concerned of their relationship with the lands or territories, or both as applicable, which they occupy or otherwise use, and in particular the collective aspects of this relationship (ILO 169).

Everyone has the right freely to participate in the cultural life of the community, to enjoy the arts and to share in scientific advancement and its benefits (UDHR).

In those states in which ethnic, religious or linguistic minorities exist, persons belonging to such minorities shall not be denied the right, in community with the other members of their group, to enjoy their own culture, to profess and practise their own religion, or to use their own language (ICCPR).

States shall protect the existence and the national or ethnic, cultural, religious and linguistic identity of minorities within their respective territories and shall encourage conditions for the promotion of that identity (Declaration on the Rights of Minorities).

Everyone shall have the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion. This right shall include freedom to have or to adopt a religion or belief of his choice, and freedom, either individually or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief in worship, observance, practice and teaching (ICCPR). “

AFTER HOH XIL, WHAT NEXT?

If China succeeds in getting Hoh Xil (and its portion of Sanjiangyuan) inscribed by UNESCO as a World Heritage natural (not cultural) property, the next step would be to nominate the rest of the Sanjiangyuan for inclusion, and perhaps the newish nature reserves beyond Sanjiangyuan, in Sichuan and Gansu provinces, all in prefectures that technically are “Tibetan autonomous prefectures.”

This is not likely to happen immediately. Making a decision on Hoh Xil will take time. UNESCO must send a scientific mission to ascertain the facts independently. The mission will come from IUCN, which sees itself as the global voice of conservation science. Its missions are narrowly scientistic, confining their gaze to the issues China has identified as grounds for inclusion.

Since China has nominated Hoh Xil as a natural and not a cultural site (or a hybrid embracing both, as is the case in China of many pilgrimage mountains on the UNESCO list) IUCN’s investigation and report will in no way focus on culture. If, as China says, echoing Sven Hedin more than a century ago, this is indeed a “no-man’s land”, a “terra incognita” with no cultural history whatsoever. When China, decades ago, applied to have the Tibetan valley of Dzitsa Degu (Jiuzhaigou) declared World Heritage, a similar process occurred, erasing its Tibetan history and connection with the upland pastures, reinventing it as a Chinese fairyland complete with Chinese goddesses.

But Jiuzhaigou is verdant; Hoh Xil is barren, alpine desert. Actually, that is only part of the bigger picture. Sven Hedin, with many pack animals to feed, frequently mentions discovering thick grass, which is the reason the chiru antelopes migrate great distances to give birth to their young in Hoh Xil and, crossing the highway/railway/oil pipeline/high voltage cables, in the Changtang (Qiangtang in Chinese) nature reserve further west.

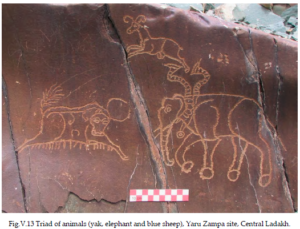

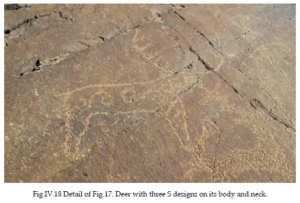

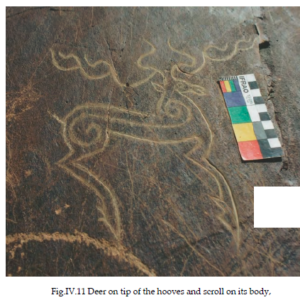

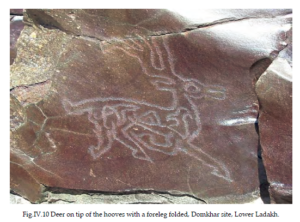

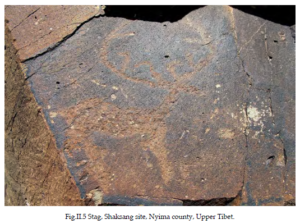

Contrary to the official master narrative of “no-man’s land”, a trope used over and over in celeb-rating the 2006 completion of the railway line, there is plenty of evidence of human culture in Hoh Xil and in in the lake land of the northern Changtang adjacent. In fact, archaeologists consider the northern Changtang to be part of Zhang Zhung, the birthplace of Tibetan civilisation. Archaeologist John V Bellezza reminds us that thousands of years ago, this now arid land had a more benign climate, more rain, endless lakes, much flattish, open land between lakes and mountains, and the lakes, lacking outlets and gradually becoming salty, were less salty when Tibetans first arrived. His photos of chiru carved into rock by Tibetans thousands of years ago are above.What today seems to be Changtang badlands, little more than cold stony desert, supported farming as well as pastoral nomadism, with stone irrigation channels and remains of villages on the Changtang still to be found today. The Changtang is full too of ancient art, carved into rocks, elaborate burial grounds, citadels and temples. Bellezza sums up his decades of painstaking investigation all over the “empty” northern plan or Changtang: “The hundreds of archaeological sites I have documented point to a land that once hosted larger numbers of more elaborately organised people as compared to more recent times.”[6] Bellezza’s many books, and lengthy tramps all over the Changtang, testify to the richness of that ancient, seminal culture; and to the changes wrought by climate change.

China’s Hoh Xil World Heritage nomination, under the heading of “Human History” (p72) supports this. It states: “According to archaeological research, many Palaeolithic stone tools were found at the alluvial fans of the south bank of the Ulan Ul Lake, which date back to approximately 20,000 years.”

However, in contemporary Tibet, “according to historical literature, before the pre-Kuomintang period, there were no residents in the Hoh Xil area due to the bitter cold and anoxic weather.” (72) Which ‘historical literature’ was consulted is not specified. There is a long history in China of restricting research to official annals, which pay little attention to “waste lands.” If Hoh Xil was cold and anoxic (thin air) in the pre-Kuomintang Qing dynasty, and is so today, it has been just so throughout human history and prehistory, with minor variations. The Chinese scientists who wrote this nomination clearly did not ask any Tibetan pastoralists about their history.

Bellezza reminds us of the deep backstory in the Changtang: “The Changthang lakes belt makes up a large portion of Upper Tibet. In the time of Zhang Zhung, these lakes contained fresher water and were subject to a generally milder climate, making them more conducive to human habitation than they are today. The rivers and streams feeding the lake basins constitute great reservoirs of freshwater, and pasturelands abound along these waterways. The all-stone corbelled residences with their hives of small cells demonstrate that the secluded, high-altitude locations were a fundamental part of religious life in the ancient Tibetan upland The construction of large and extremely durable citadels and burial grounds in Upper Tibet points to a people in possession of considerable technological expertise. The great variety of necropolises in the region indicates that intricate beliefs were attached to death and the afterlife. A high level of cultural sophistication is also evidenced in the fine-quality copper alloy and iron objects attributed to archaic era Upper Tibet. The Tibetan textual patrimony that has come down to us since the early historic period describes this material culture with great flourish. Eternal Bon scriptures proclaim that the priests and rulers of Zhang Zhung were attired in sumptuous fur robes, and that they wore turquoise, patterned agates, and meteoric iron talismans, as well as brandishing many kinds of weapons. These literary accounts also hold that the ancient priesthood was very adept in the practice of astrology, divination, magic, and medicine.”[7]

Given this cultural history, present skilful pastoral land use, and abundant archaeological treasures, Bellezza specifically appeals to UNESCO to step in to preserve what remains.[8] This would entail revising the nomination to include culture. China has led the way in proposing World Heritage sites that are classified both as natural and cultural, including many famous Buddhist pilgrimage mountains around China. UNESCO could, in light of the rich history and prehistory of the Tibetan drylands, propose such a reclassification. This move to a more inclusive status –in UNESCO jargon, such sites are called hybrids- is a middle way between the extremes of approving or disallowing China’s current proposal.

CHINA AND UNESCO

The UNESCO World Heritage centre encourages governments to submit proposed World Heritage sites on its “tentative list”, which is public and online. http://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/state=cn

China has 54 properties queueing to become World Heritage, some were proposed as far back as 1996. Some of these are Tibetan, notably #10, the sentinel towers built by Tibetans in Kham centuries ago to warn of danger, usually from lowland China; and #52, the Yarlung valley of central Tibet, sacred to the earliest lineage of Tibetan kings (Yalong in Chinese). At #32 on the list is Qinghai Hoh Xil, first proposed in January 2015, a nomination now proceeding.

- Ancient Porcelain Kiln Site in China (29/01/2013)

- Ancient Residences in Shanxi and Shaanxi Provinces (28/03/2008)

- Ancient Tea Plantations of Jingmai Mountain in Pu’er (29/01/2013)

- Archaeological Sites of the Ancient Shu State: Site at Jinsha and Joint Tombs of Boat- shaped Coffins in Chengdu City, Sichuan Province; Site of Sanxingdui in Guanghan City, Sichuan Province 29C.BC-5C.BC (29/01/2013)

- Baiheliang Ancient Hydrological Inscription (28/03/2008)

- China Altay (29/01/2010)

- Chinese Section of the Silk Road: Land routes in Henan Province, Shaanxi Province, Gansu Province, Qinghai Province, Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, and Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region; Sea Routes in Ningbo City, Zhejiang Province and Quanzhou City, Fujian Province – from Western-Han Dynasty to Qing Dynasty (28/03/2008)

- City Walls of the Ming and Qing Dynasties (28/03/2008)

- Dali Chanshan Mountain and Erhai Lake Scenic Spot (29/11/2001)

- Diaolou Buildings and Villages for Tibetan and Qiang Ethnic Groups (29/01/2013)

- Dong Villages (29/01/2013)

- Dongzhai Port Nature Reserve (12/02/1996)

- Dunhuang Yardangs (30/01/2015)

- Expansion Project of Imperial Tombs of the Ming and Qing Dynasties: King Lujian’s Tombs (28/03/2008)

- Fanjingshan (30/01/2015)

- Fenghuang Ancient City (28/03/2008)

- Haitan Scenic Spots (29/11/2001)

- Heaven Pit and Ground Seam Scenic Spot (29/11/2001)

- Historic Monuments and Sites of Ancient Quanzhou (Zayton) (20/01/2016)

- Hua Shan Scenic Area (29/11/2001)

- Jinfushan Scenic Spot (29/11/2001)

- Jinggangshan–North Wuyishan (Extension of Mount Wuyi) (30/01/2015)

- Karakorum-Pamir (29/01/2010)

- Karez Wells (28/03/2008)

- Kulangsu (29/01/2013)

- Liangzhu Archaeological Site (29/01/2013)

- Lingqu Canal (29/01/2013)

- Maijishan Scenic Spots (29/11/2001)

- Miao Nationality Villages in Southeast Guizhou Province: The villages of Miao Nationality at the Foot of Leigong Mountain in Miao Ling Mountains (28/03/2008)

- Nanxi River (29/11/2001)

- Poyang Nature Reserve (12/02/1996)

- Qinghai Hoh Xil (30/01/2015)

- SanFangQiXiang (29/01/2013)

- ShuDao (30/01/2015)

- Site of Southern Yue State (28/03/2008)

- Sites of Hongshan Culture: The Niuheliang Archaeological Site, the Hongshanhou Archaeological Site, and Weijiawopu Archaeological Site (29/01/2013)

- Sites for Liquor Making in China (28/03/2008)

- Slender West Lake and Historic Urban Area in Yangzhou (28/03/2008)

- Taklimakan Desert—Populus euphratica Forests (29/01/2010)

- The Alligator Sinensis Nature Reserve (12/02/1996)

- The Ancient Waterfront Towns in the South of Yangtze River (28/03/2008)

- The Central Axis of Beijing (including Beihai) (29/01/2013)

- The Chinese Section of the Silk Roads (22/02/2016)

- The Four Sacred Mountains as an Extension of Mt. Taishan (07/04/2008)

- The Lijiang River Scenic Zone at Guilin (12/02/1996)

- Tianzhushan (30/01/2015)

- Tulin-Guge Scenic and Historic Interest Areas (30/01/2015)

- Western Xia Imperial Tombs (29/01/2013)

- Wooden Structures of Liao Dynasty—Wooden Pagoda of Yingxian County,Main Hall of Fengguo Monastery of Yixian County (29/01/2013)

- Wudalianchi Scenic Spots (29/11/2001)

- Xinjiang Yardang (30/01/2015)

- Yalong, Tibet (29/11/2001)

- Yandang Mountain (29/11/2001)

- Yangtze Gorges Scenic Spot (29/11/2001)

For China, modernising Tibet has been a menu with many options. Modernising in some areas means mineral extraction, urbanisation and industrialisation, with networks of highways, railways, fuel pipelines and power grids to connect these enclaves to each other and to lowland China. When people think of modernity and development, that’s what usually comes first to mind.

But modernity can also mean setting aside areas of limited human utility for conservation, showing that the state cares for biodiversity and international treaties meant to protect wildlife. Drawing red lines round nature reserves, national parks, even declaring World Heritage areas, all declare the state to be in command, inscribing its agenda on the land and people.

Modernity by whatever means possible has long been China’s agenda for Tibet, making the state a tangible presence, in lands that have never had much governing from anyone.

It makes immediate sense that industrial, extractive and urban enclaves are located in areas endowed with minerals, hydropower potential, along trade routes, on rivers, in well-watered districts where the terrain is rolling rather than rugged. These are what economists call factor endowments.

That leaves the badlands: the alpine deserts of upper Tibet, where even the last wisps of the Indian monsoon and the East Asian monsoon seldom reach. High, dry and most of the year intensely frigid, these are the waste lands, where modernity instantiates as nature reserves, nobly serving a purpose wider than immediate human wealth accumulation. This is modernity at its best, paying due heed to the needs of nature.

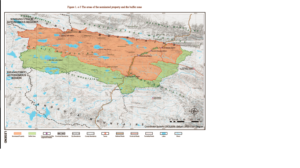

This evaluation considers all three of the very large nature reserves China has declared, in the most arid portions of the Tibetan Plateau. The Changtang, Hoh Xil and Sanjiangyuan (Three River Source) nature reserves are considered together because they are together, in one contiguous, interlocking belt that stretches right across the entire Tibetan Plateau west to east. In this trio of nature reserves, Hoh Xil is literally central, with Sanjiangyuan to its south and east, Changtang to its west. If Hoh Xil becomes UNESCO World Heritage, the others will most likely follow. In fact over 41 per cent of the Hoh Xil area nomination is actually Sanjiangyuan, now redesignated as “buffer zone” of the proposed Hoh Xil World Heritage area.

But modernist management simplifies its objectives to conform to the remit of the administering agency of state, to the point where land use outside of official policy is at best seen as problematic, at worst illegal, to be punished. The wild herds of chiru antelopes which migrate annually into this remote area to give birth during the summer flush of grass growth are now the sole purpose of this northern plain –Changtang in Tibetan. The migratory chiru, the wild yak, the wolf, bear, kiang (wild donkeys) and wild drong yaks, are now the sole, exclusive legitimate land use. The conflict between conservation and human use was foundational, and has become China’s model for extending exclusion to other areas of Tibet, in the name of wildlife conservation or, more recently, the growing of ungrazed grass, in the name of carbon capture and climate change mitigation.

From the outset, this was an American idea whose time had come. Advocacy was led by George Schaller, of Bronx Zoo and its Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), an effective lobby for this dualistic zero/sum model. The extent of official protection, to the exclusion of other human uses, especially pastoralism, has increased to the point that the UN now classifies the North Tibetan Plateau-Kunlun Mountains alpine desert as having 67 per cent of its total area under official protection, far in excess of the global goal of 17 per cent of each ecoregion protected.[9] This ecoregion is both frigid and arid, being the highest plateau terrain, and furthest from the reach of rain bearing clouds in any direction. It is this ecoregion where the push for official protection began, as a global as well as a Chinese campaign whose public face was George Schaller, of the Wilderness Conservation Society. To Tibetans, this is upper Tibet, seldom visited, but important as the area where antelope go to give birth, in the brief summer when herbage is plentiful.

Tibetans are glad this vast northern plain, the Changtang, is officially protected. They are less sure that protection should extend to the wild yaks, lest they mate with their domestic females, undoing generations of breeding of yaks of a manageable size and docility. Other than that, the Tibetan pastoralists who make occasional use of the Changtang are pleased official protection is meant to end the indiscriminate slaughter of wild animals which was a popular sport among Chinese soldiers stationed in Tibet in the revolutionary period.

Schaller writes at length, and with passion, about his campaign to protect the Changtang: “The Tibetan Plateau had infected me, particularly the Chang Tang. The name enchants. It conjures a vision of totemic loneliness, of space, silence, and desolation, a place of nowhere intimate –yet that is part of its beauty. I had long wanted to explore its secrets. In 1984 I finally had the opportunity to penetrate its vastness.”[10] By 1991, Schaller was ready to propose official state protection: “After my surveys in1988 and 1990, I discussed the need for a reserve with the Tibet Forest Bureau, and we also considered potential reserve boundaries and options for managing livestock and wildlife. The creation of a reserve is a complicated political process, needing the cooperation of forestry, agriculture, military, and other departments. However, the government of the Tibet Autonomous region was then becoming seriously concerned about conservation, and in December 1990 it approved in principle the establishment of a Chang Tang Nature Reserve.”[11]

Although there is neither forestry nor agriculture in the Changtang, these were the departments in charge, along with the military, who Schaller lobbied. Entirely absent from the negotiations were the Tibetan nomads. From the outset, inherent in Schaller’s case, was a sharp critique of pastoral nomads as destructive of wildlife, especially of the wild yaks, but also of the kiang wild donkeys and chiru antelopes. Schaller continued campaigning for the Nature Reserve to be bigger, and to press for official rules excluding Tibetan pastoralists: “Some areas need to be closed, at least during certain seasons. Use of the basin by nomads should be carefully regulated. Population growth will make sustainable management of resources in the reserve increasingly difficult. To limit such growth, further immigration should be prohibited.”[12]

The seed was sown. Even though Schaller’s own narrative is of the slaughter being instigated by officials, to feed Chinese labourers on construction projects[13] and Muslim Chinese gold diggers,[14] Schaller took every opportunity to express his concern that Tibetan pastoralists would build permanent homes in the Changtang and degrade the pasture. [15] Schaller reports a party secretary assuring him that hunting has been banned, yet Schaller noticed a freshly shot Tibetan gazelle in the back of the official’s SUV.[16] But he was concerned that the 1993 legislation officially establishing the Changtang nature reserve, an area the size of Schaller’s native Germany, was “not as a wilderness to be set aside as a park but as a multiple-use area where the needs and aspirations of the nomads must be considered.”[17]

CREATING WILDERNESS ON THE RANGELANDS

The recourse to state power as the ultimate solution to problems of conservation, and the exclusionary power of the state as the guarantor of successful conservation, espoused by Schaller, has increasingly become China’s model, and rationale, for the creation of protected areas, not only in the remote Changtang but in the best pasture lands of the Tibetan Plateau.

The model outcome is an ideal type, a Platonic form existing nowhere on the inhabited earth, of pristine wilderness. The romantic ideal of wilderness is almost by definition, uninhabited by human animals. Schaller, whose soul aches for the lonely wilderness, and who tells us how disinclined he is to listen to nomads, [18] wants nothing less than the wildest of wildernesses, in which the state stands guard to prevent any human predation.

This sharply dualistic opposition of man and nature, hardly Schaller’s invention, has increasingly informed China’s approach to Tibet. We now have, on official maps and plans, a sharp, territorial distinction between Tibet’s production landscapes, which are shrinking, and protection landscapes, which are growing.

Man, the despoiler of nature, is an embedded concept of European culture, not of China’s. It is the obverse of man, whose rightful place is to proclaim dominion over all the earth and all therein. Man as part of nature is not part of the European tradition, but it is in Chinese Taoism and Buddhism, and in the figure of the cultivated Confucian sage who cultivates learning for one’s self by writing nature poetry arising from immersion in nature. When China a century ago cast aside its traditions, and instead embraced Mr. Science, the sharp distinction science makes between observer and the observed became the norm.

In a revolutionary, irreligious China, nature became the ultimate Other. Mao exhorted the Chinese to conquer nature, by sheer force of human will, which could even remove mountains. Inevitably, given the opposition of man and nature, there have also been times, especially in more recent years, when nature has been on a pedestal, admired and revered for offering everything we humans lack.

China’s system of nature reserves, the term China uses for officially protected areas, is squarely based on nature as Other, to be kept apart from the depredations of humanity by strict regulations and red lines on maps. China’s nature reserves are places of exceptional beauty, and especial richness of rare wildlife, or landforms of breathtaking angularity, or hotspots of biodiversity. A survey of nature reserves published in 1989 groups its list of all the reserves that then existed into broad categories: representative samples of natural ecosystems, paradises for rare animals, refuges for ancient plants, beautiful natural parks, and natural geology museums. [19] Those are the chapter headings, following common practice worldwide.

RECOMMENDATIONS:

- Hoh Xil should be classified as a hybrid, mixed site of both natural and cultural significance. UNESCO should advise China its application cannot proceed solely as a natural site. Human use of Hoh Xil is as old, perhaps older than at Yarlung, Tibet’s valley of the kings, which China put on the World heritage tentative list in 2001, explicitly as a “mixed” natural/cultural property, listing in some detail its historic importance to Tibetans and thus to the world.

- Any mission sent on behalf of UNESCO to assess Hoh Xil should include not only wildlife scientists from IUCN, but also archaeologists from ICOMOS and/or ICROMH, capable of surveying 77,000 km2 of drylands with little archaeological research conducted until now.

- Any mission on behalf of UNESCO should be given time and access to this huge area, almost twice the size of Switzerland, to ensure there is no mining or resource extraction anywhere within the proposed World Heritage area. Mindful of UNESCO’s recent and repeated experiences of mining in the Three Parallel Rivers of Yunnan, any repeat failure to impose UNESCO standards is unacceptable.

- UNESCO should obtain assurances that any plans to divert waters of upper Yangtze tributaries to the upper Yellow River do not in any way impinge on the proposed Hoh Xil World Heritage property.

- Any management plan for a World Heritage Hoh Xil property must include participatory co-management; with local pastoralist communities empowered to jointly make decisions, together with the state party, as equals. The experiences of WWF and Conservation International in the Changtang and Hoh Xil nature reserves show that it is possible to achieve conservation objectives and enhance local livelihoods at the same time. UNESCO faces a real choice between a proven record of local Tibetan communities successfully protecting endangered wildlife by putting their lives on the line; and state-sponsored official conservation amid a tourism surge.

- UNESCO should prioritise meeting with civil society in Hoh Xil, notably with the Tibetan NGOs campaigning for Chumarleb to be declared a Sacred Natural Site (SNS). SNS is a concept more closely aligned with traditional Tibetan drivers of effective stewardship and active protection of wildlife from poachers. SNS does not necessitate an overpowering state presence, or decision-making centralised in distant cities. SNS is in many ways preferable to World Heritage inscription, as it respects community control and does not encourage mass visitation and a mass tourism industry. Sacred natural sites have long served as a primary conservation network for conserving nature and culture. The rapid degradation and loss of sacred natural sites severely threatens critical biodiversity, ecosystem services, cultural resources and even ways of life. Recognizing sacred natural sites supports community autonomy, promotes effective management and gives voice, rights and action to local people. Faith, spirituality and science provide different but complementary ways of knowing and understanding human-nature relationships. Successful co-existence of sacred natural sites and modern economic imperatives requires a better understanding of their interrelationships, and of the broad values and benefits of sacred natural sites for human wellbeing and development. Sacred natural sites as nodes of resilience, restoration and adaptation to climate change offer opportunities for recovering ecologically sound, local ways of life. Local commitment, wide public awareness, supportive national policies and laws, state protection and broad international support are essential for the survival of sacred natural sites.[20]

******************

If you wish to join the campaign to make Hoh Xil a Sacred Natural Site, under Tibetan community control, please contact:

Stephan Dömpke

World Heritage Watch e.V.

Palais am Festungsgraben

10117 Berlin, Germany

Tel. +49 (30) 2045-3975 landline

contact@world-heritage-watch.org

[1] YAO Xiaojun, LIU Shiyin, LI Long, SUN Meiping, LUO Jing, Spatial-temporal characteristics of lake area

variations in Hoh Xil region from 1970 to 2011; Journal of Geographic Science. 2014, 24(4): 689-702

YAO Xiaojun, LI Long, et al, Spatial-temporal variations of lake ice phenologyin the Hoh Xil region from 2000 to 2011, J. Geogr. Sci. 2016, 26(1): 70-82

[2] A detailed examination of China’s regulatory regime for protected areas, and George Schaller’s role in persuading China to establish nature reserves in Tibet, are to be found in Wasted Lives, Tibetan Centre for Human Rights & Democracy, 2015, portions of which are reproduced here with permission. http://tchrd.org/wasted-lives-new-report-offer-fresh-insights-on-travails-of-tibetan-nomads/

[3] Regulations of the People’s Republic of China on Nature Reserves 中华人民共和国自然保护区条例 [已被修订CLI.2.10458(EN), Decree No. 167 of the State Council, 10-09-1994

[4] http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/china/2015-01/27/c_133951132.htm?utm

[5] Harry Jonas, Dilys Roe and Jael E. Makagon, Human Rights Standards for Conservation: An Analysis of Responsibilities, Rights and Redress for Just Conservation, International Institute for Environment and Development, 2014

[6] John Vincent Bellezza, The Dawn of Tibet: The ancient civilisation on the roof of the world, Rowman & Littlefield, 2014, 8

[7] Dawn of Tibet, 298-9

[8] Dawn of Tibet, 166

3 Asia Protected Planet Report 2014: Tracking progress towards targets for protected areas in Asia, UNEP, 2014, 26 http://wdpa.s3.amazonaws.com/WPC2014/asia_protected_planet_report.pdf

[10] George B Schaller, Tibet Wild: A naturalist’s journeys on the roof of the world, Island Press, 2012, 2

[11] George B. Schaller, Tibet’s Hidden Wilderness: Wildlife and nomads of the Chang Tang Nature Reserve, Abrams, 1997, 56

[12] Schaller, Tibet’s Hidden Wilderness, 154

[13] Schaller, Tibet’s Hidden Wilderness, 62

[14] Schaller, Tibet’s Hidden Wilderness, 157

[15] Schaller, Tibet’s Hidden Wilderness, 125

[16] Schaller, Tibet’s Hidden Wilderness, 91

[17] Schaller, Tibet’s Hidden Wilderness, 124

[18] Schaller, Tibet’s Hidden Wilderness, 124

[19] Li Wenhua and Zhao Xianyang, China’s Nature Reserves, Foreign Languages Press, 1989

[20] This recommendation owes much to: McNeely, Jeffrey; Verschuuren, Bas; Wild, Robert; Oviedo, Gonzalo. Sacred Natural Sites. : Taylor and Francis, 2012.

One reply on “EMPTYING TIBETAN LANDS FOR SAFARI TOURISM”

I am so pleased to see in your blog a discussion of the relationship between the ancient cultural and ecological setting and the contemporary scene in pastoral Tibet. Thank you also for making an appeal to conserve the environment and heritage of the region. May your words reach far and wide.