Blog two of three on Tibetan nomads, frogs, green iron rice bowls and highland clearances

CAN NOMADS, WILDLIFE AND YAKS STILL COEXIST SUSTAINABLY?

China’s program of steadily depopulating rural Tibet, especially in the upper watersheds of the Yellow, Yangtze and Mekong Rivers, is not the only possible way ahead. Quietly, Chinese NGOs such as Shan Shui and Plateau Perspectives have shown in practice that rangelands and pastoralists do go together, in the future as well as in the past, doing “eco-husbandry”, as active, skilful landscape managers.

A key figure in these on-the-ground experiments in sustainable drogpa pastoralism is Du Fachun, even though his decades of immersion in the back country of Tibet has been appropriated by China’s official propaganda media, reducing him to bumper sticker simplification.

Du Fachun’s three decades of careful fieldwork in Tibet and other minority ethnicity areas, detailing how relocation of traditional land managers works out in practice, has been reduced by the party-state propaganda machine to a single word. Tibetans, Du Fachun said, are “amphibious”, at home on land and water, adaptable. An academic career leading research teams interviewing urbanised pastoralists over decades boils down to one word.

How reassuring to know Tibetans are adaptable. It makes the mission of the state, to turn rural Tibet into wilderness, and Tibetans into modern citizens literate in Chinese, easier.

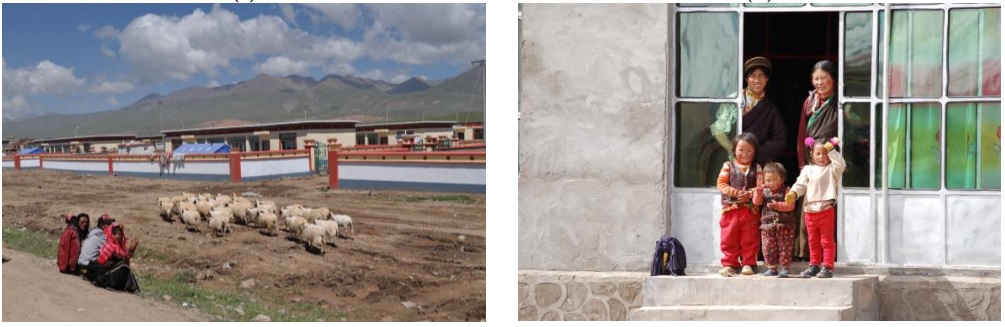

CCP media Global Times reports on resettled Tibetans on the outskirts of Gormo, in Changjianyuan village:

However, if one looks beyond that one word, to the lifework of Du Fachun, his careful questioning of sedentarised Tibetan nomads reveals their exit from a constrained life of poverty on the open range, under strict herd size limits, to ongoing, even worse poverty on the urban fringes. From poverty to poverty is not the story official China likes to tell, and Du Fachun’s social scientific work at Institute of New Rural Development, Yunnan University, has been ignored, in favour of the sedentarisation/civilisation success story inspected and validated by Xi Jinping in 2016.

“NEITHER DEER NOR HORSE, NEITHER COW NOR DONKEY”

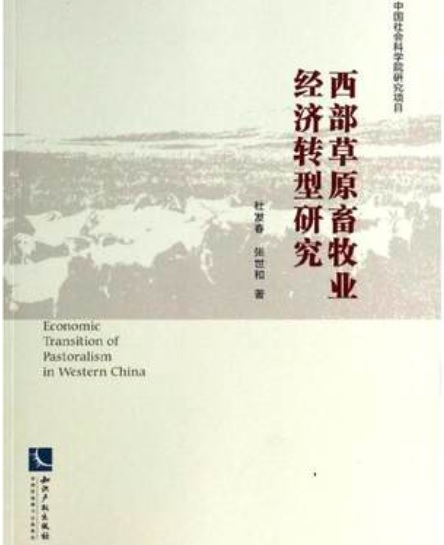

Du Fachun 杜发春did manage to gather his team’s fieldwork over decades into a book published in 2014, which shows the failure of the central state to live up to its promises of lifting the herder masses out of poverty by relocating them to straight striplines of concrete boxes lining the southern approaches to the industrial city of Gormo (Golmud in Chinese). Those straight lines of regular modernity line the road, but are kept 15 to 20 kms from the Han industrial city, where only standard Chinese is spoken. Situating the resettled thousands well out of town but hundreds of kms from their customary landscapes, is intended to be salutary, minatory, a halfway house or bardo, suspended between worlds, a first entry into history and civilisation, a test of whether they can reinvent themselves, ideally with primary loyalty transferred to the state.

Du Fachun, however, found these geometric containers of human lives far from fulfilling their pedagogic promise. They were indeed a bardo, a suspension of life, awaiting the eventual plunge into some new rebirth. His 2014 book, summing up a decade of interviews as fresh waves of displaced were deposited in these new model villages, shows a picture quite different to the upbeat depictions in official media.[1] The book discusses the vulnerability, conflict and integration of ecological migration enclaves; analyzes the composition, follow-up livelihood and employment types of Sanjiangyuan relocation herdsmen with a large number of survey data.

It finds that limited government subsidies make it difficult to maintain the promised follow-up livelihood of relocated herdsmen. The employment rate of immigrants is low, the urban adaptability is weak, and the environmental recovery effect of the emigration place is poor. Du Fachun’s comparative study of the experience and lessons of foreign ecological immigrants emphasizes that it should be avoided or reduced as much as possible. Social problems that may be caused by ecological immigration; a series of alternative policies are proposed for the dilemma and problems of Sanjiangyuan ecological immigrants.

Du Fachun draws on worldwide experience. Next year, 2012, he published a low key critique[2] of official policy and its consequences, arguing that shengtai yimin resettlement policy “rationale and consequences need rethinking, from both an ecological and socio-economic perspective. This article draws on field research and a case study in Madoi County to argue the logic for resettlement, to examine its socio-economic consequences and environmental effects, and to explore possible solutions. Grassland degradation cannot simply be attributed to overgrazing and population growth, hence the idea of improving grassland by simply implementing resettlement projects may sound implausible. The paper then analyses the process and policies of resettlement and examines its socioeconomic changes and environmental effects. Although the herders are provided with free accommodation and a certain amount of subsidies, many cannot adapt well to the new urban lifestyle and some have an identity crisis, while their quality of life after resettlement is in general not very satisfactory due to high living expenses.

“The 2004 Sanjiangyuan General Plan closely links eco-resettlement with efforts to restore grazing land to grassland. The plan called for the relocation of 55,774 people (10,142 herding households), the reduction of livestock by 3.2 million sheep units, the imposition of a ten-year grazing ban on the abandoned grasslands, and a period of off-season and rotational grazing (QECC 2003). Herders who agreed to be resettled would receive compensation. Data from the Ecological Resettlement Management Office of the Qinghai Development and Reform Commission indicates that eighty-six new settlement villages were built between 2004 and 2010. Small towns or suburbs were also established to house herders who left the grassland. As a result, eighty-six resettlement communities sprouted up in urban areas or rural townships, near markets along the state highway, and in neighbourhoods around fodder bases in the Sanjiangyuan.

“Each resettlement household was provided with a 45 sq m house (valued at RMB 800/sq m), a 120 sq m barn (priced at RMB 200/sq m), and a RMB 400 one-off taxi fare for one family to move to a new town. In addition, the government implemented a compensation policy of RMB 8,000 annually for families (regardless of family size) which continued to obey the ten-year grazing ban.

BETWIXT IN BARDÖ

“The eco-migrants experienced drastic changes in their livelihood security, identity and adaptation. First, livelihood security: according to interview data, ecological resettlement, to some extent, improved the housing, education, medical care and transportation conditions of the migrants, but their overall living standard actually fell. The following are the comments made by interviewees. ‘Everything here costs money. A slice of meat costs 10 RMB, so does a bag of livestock dung

“We can’t afford them. Yet when we lived on the grassland, we didn’t need very much at all. We got everything from our livestock. Before we came here, we sold all our livestock, tore down our houses, and gave our grasslands back to the state. Now we can’t find any jobs and we just stay at home doing nothing all day long.’ (Mr Dawa, 52, Golok Xincun, September 2009)

“‘My family had about a hundred yaks and three hundred sheep. Our grassland was about 4,600 hectares. We were satisfied with our lives. However, after we moved to town my whole family [ten people] mainly relied on government subsidies. We received about RMB 10,000 per year, which was less than our income from raising two yaks on the grassland. What’s worse, our expenses here are much higher due to inflation. My family seldom buys meat or milk nowadays.’ (Mr Jiayang Danzeng, 55, Heyuan Xincun, September 2009)

“Most resettled herders interviewed had similar accounts. They relied on subsidies because few alternative job opportunities had been created for them. However, these subsidies were insufficient to meet daily expenses for food, water, electricity, clothing, transportation and religious activities. Moreover, the price of daily necessities was driven up by increasing inflation in China, but resettlement subsidies were not correspondingly increased.

“Some resettlers undertook various off-farm activities, such as digging up caterpillar fungus, knitting blankets for sale, operating small businesses, or working as security guards, taxi drivers, or construction workers. The unstable nature of these low-income jobs resulted in their standard of living declining after resettlement. Local government invested funds and effort to provide technical training and jobs, but it proved hard to create alternative industries for the resettlers. Qinghai Provincial Poverty Alleviation Office tried to support the establishment of a Tibetan blanket manufacturer in Heyuan Xincun. Ecological settlers in the village held great hopes for the factory, but it went bankrupt in October 2010. A local official from Gyaringhu rural township commented that the cost of transporting raw materials from the provincial capital of Xining was very high, and the skills of the eco-migrants were generally poor. Second, identity: eco-migrants faced unfamiliar surroundings after resettlement, and some experienced culture shock and social disruption (Li 2008).

“Migrants who moved to new prefectures had identity crises due to increasing marginalization. Some joked that by leaving their grassland, they had lost their identities as herders. Their new identity had not yet been formed.

“They did not hold urban resident registration identity cards to become citizens. Most of them could not adapt well to urban life. Instead, they were rather like the odd-looking Père David’s Deer – neither deer nor horse, cow nor donkey. These frustrations and uncertainties further led to their dissatisfaction with the poor quality of infrastructure, land management, education and social security in the new resettlement villages.”

That same year, 2012, Du Fachun teamed up with Cao Qian, a Helsinki University sociologist, and published in Chinese on global experience of projects to enhance rather than cancel nomad livelihoods while improving ecological outcomes.[3] Du Fachun expanded further on what China can learn from others in 2014.[4] He emphasized that emigration as a solution to the presumption that pastoralists on pasture are incurably poor, and emigration as solution to land degradation, have both been abandoned worldwide, in favour of a new paradigm of inclusiveness and co-management of common pool resources.

Du Fachun has quietly introduced China to new thinking. Usually China is quick to adopt new approaches, ever keen to be up with the latest, even to excel and become exemplary leader in implementation of new concepts. But not when it comes to those uncivilised, backward drogpa nomads of Tibet, who actually could do more for the land, more for wildlife and more for China on their land rather than off it.

THOSE AMPHIBIOUS TIBETANS

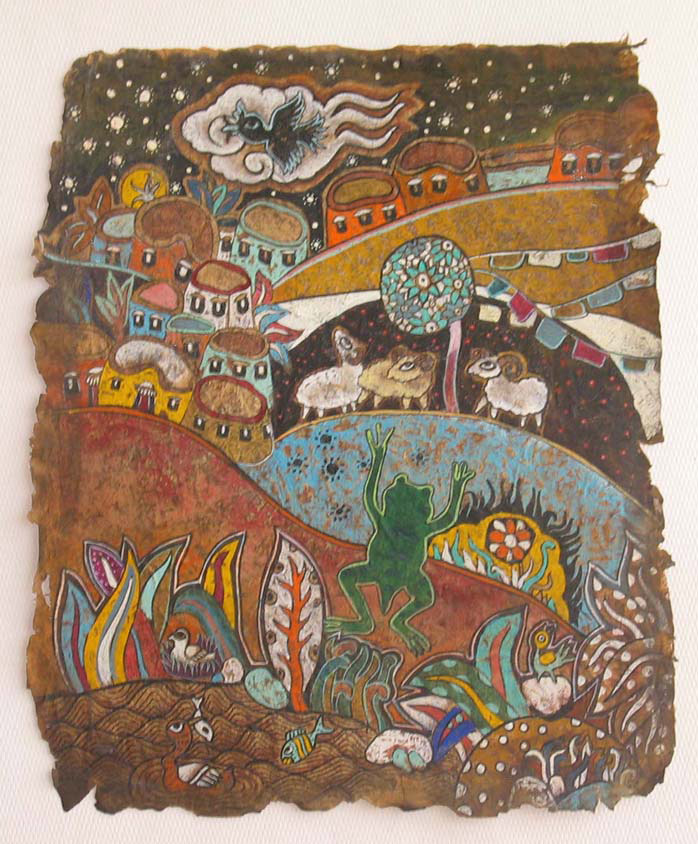

Du Fachun describes the Tibetans as “amphibious”, a metaphor for adaptability, at home on land or in the water. Official propaganda media are quick to pick up this phrase to validate urbanisation of drogpa nomads as a good thing.

Yet it is a trope worth thinking with further. Is the new concrete settlement the land or the water? Is the rangeland, with its endless braided streams, the land or the water? Surely the sub urban concrete, these days often an apartment tower, is land, complete with police station, bright lights and surveillance cameras. Surely the open range, a sea of grass waving in the wind, is the water.

Modern China, like any modern state, has a passion for separating land and water, each in their own regulated space. Revolutionary China set about draining the swamps, haunted by memories of the revolutionary soldiers sucked into Tibetan marshes on their Long March. Today’s China is obsessed with Tibet’s redefined primary function, the provision of water to lowland China. In contemporary jargon of environmental services, this means both water retention, and water provisioning. Tibet is now engineered to retain pure water as much as possible, no longer in the melting glaciers, but in the flow of the greatest of rivers –the uppermost Yellow, Yangtze and Mekong- as they flow gently across the gently dipping meadows of Amdo where only the slight gradient of the plateau floor keeps them moving through the mountainous lip of this enormous island in the sky. Only as those rivers incise their way down deep valleys do they become wild and, in modern eyes, suitable for damming, for endless cascades of dams. This is mostly for the electricity but also for water retention, to smooth out the annual summer monsoon influx to make water available far downriver long after the monsoon clouds have gone.

All of this engineering of landscape requires that land and water be separated and regulated, which may well, incidentally, require shifting human populations out of the way. More displacements.

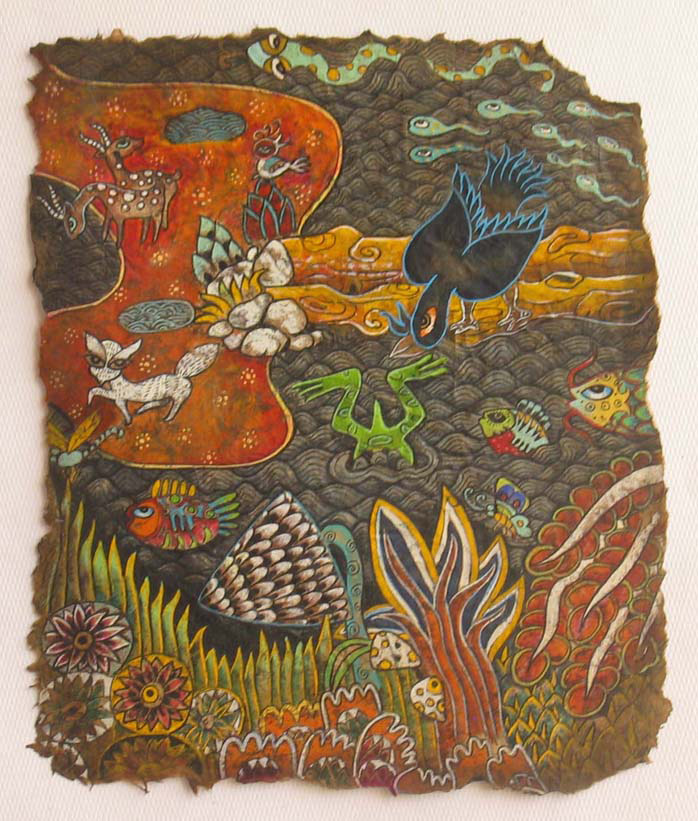

Yet the alpine meadow pasture lands are rich in herbage because land and water mingle, that is what makes them fertile and abundant. The Amdowa Tibetans are people of both land and water, of horses and cattle readily fording streams, of seasonal nomadic shifts of camp upstream to the high country before the summer rains set in fully, returning to the lower winter pasture after the summer rains, and swollen rivers, have passed. Tibetan nomads have always preferred to camp near a stream.

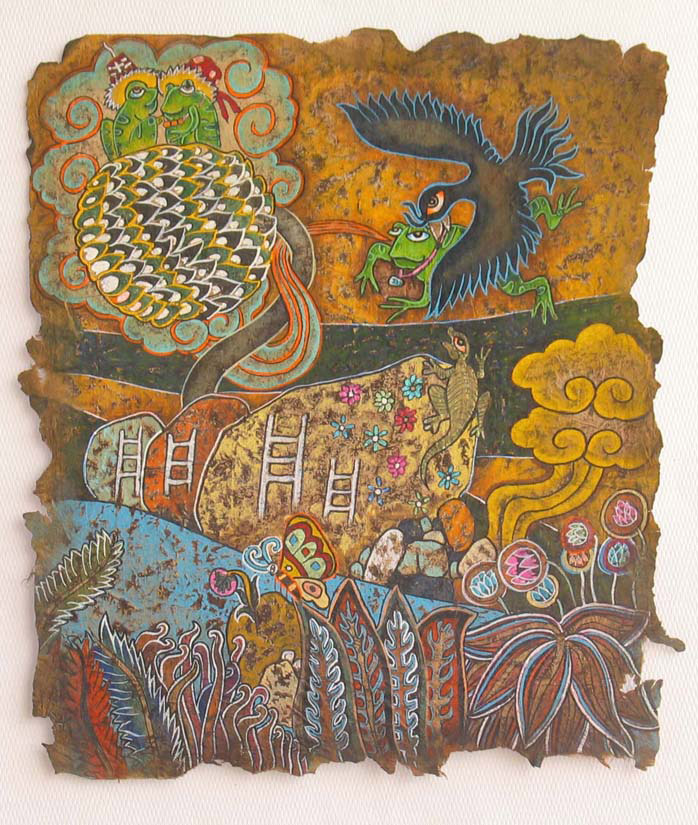

Amphibians, frogs for example, are not only at home on land and in the water, they move between them, their life cycle is built around transitioning back and forth. How can Tibetans still be adaptably amphibious when stranded 500 kms from water, and from home?

For the thousands of Tibetans of Changjiangyuan village, 500 kms from their traditional rangelands, the loss of water is as deep as the loss of pasture. Changjiangyuan and nearby Kunlun National Culture Village, the Potemkin villages of China’s nomad resettlement program, were inspected by Xi Jinping in 2016. Changjiangyuan is named after the absent river, with an absent name in an absent language. Changjiang is the Yangtze, in Tibetan the Dri Chu, but even Han China only calls it the Changjiang a long way downriver, well past Tibet, at the Three Gorges. Upriver, in Tibet, it is, for all Chinese, the Tongtian and further up, closest to the glacial source, the Tuotuo.

Yet the model Tibetans of Changjiangyuan –Yangtze source- village are stranded in a parched land, not only 500 kms from home, but far from all water, on the edge of the oil and gas fields of Tibet, in the arid Tsaidam Basin. Gormo city (Golmud in Chinese) is the second biggest city of Amdo, busily turning the millions of tons of Tibetan lake-bed salts and oil extracted annually over many decades, into petrochemicals, chemical fertilisers, plastics, explosives and myriad producer goods, the essential materials for distant manufacturers. China made Golmud the most industrialised part of Tibet despite its lack of rain, because that is where the oil was found and later, the gas fields.

So why did China decide to park thousands of Tibetans, deemed surplus to the requirements of “ecological civilisation” in a semi-desert? The answer does not lie in the soil. The soils of the Tsaidam basin are saline, infused with salts deposited in this lowland (by Tibetan standards) over millions of years of rainfall and evaporation. These soils do not bear crops, even if irrigation water could be found. Chinese scientists, led by Li Runjie 李润杰 did eventually manage, by decades of experimentally draining salts to the subsurface soil, to actually grow a good crop of wheat on 2000 mu (133 hectares) of Hexi State Farm land.[5]

There are no Tibetan livelihoods to be found based on land or water anywhere near the new settlements. Their location is due to their proximity to a Chinese city. They are well outside the “walls” of this heavy industrial base of Golmud, separated by 15 to 20 kms of desert and expressway, designed to keep them out of both customary pasture and the new city, yet lure them to city life, where all facilities, services, offices and permissions, comforts and shopping malls are to be found, as well as the peteochemical refineries.

Because the oil and gas had to be deliverable to the heavy industries of distant Gansu Lanzhou, China was quick to push through a highway, then a railway which much later was extended to Lhasa, and most recently an expressway. Tankerwagon trainloads continue to haul Tibetan oil from Gormo to Lanzhou, two million tons extracted each year, and also haul the refinery products of the Gormo petrochemical plants. This then is the perfect spot for a Tibetan nomad settlement, not in an exclusively Han Chinese city, but on its outskirts, strung out along the road, on display to all who pass by on their long highway drive towards Lhasa or Lanzhou. This is where the drogpa have landed, where even water to drink must be a dispensation of state power. This is hardly the amphibious life Du Fachun has in mind.

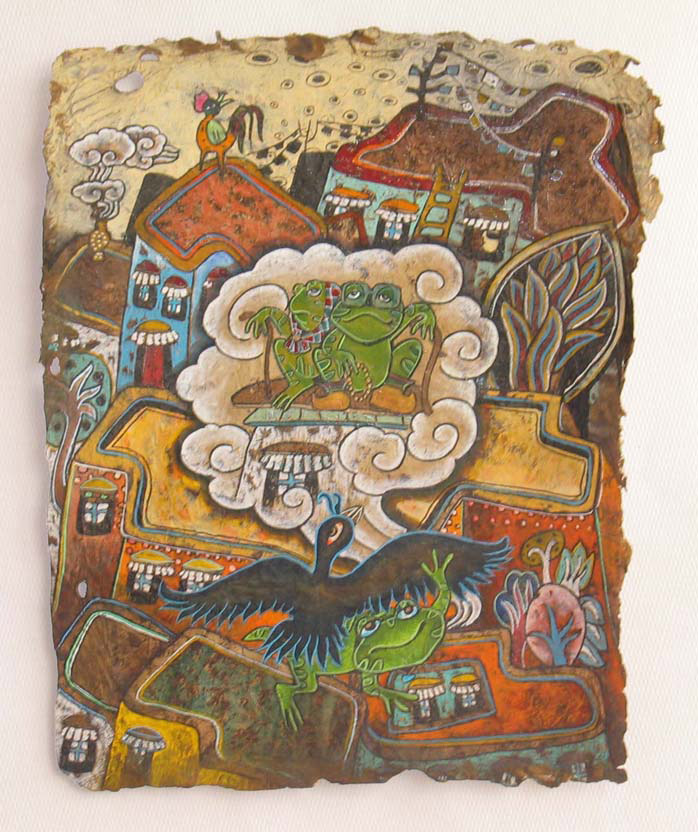

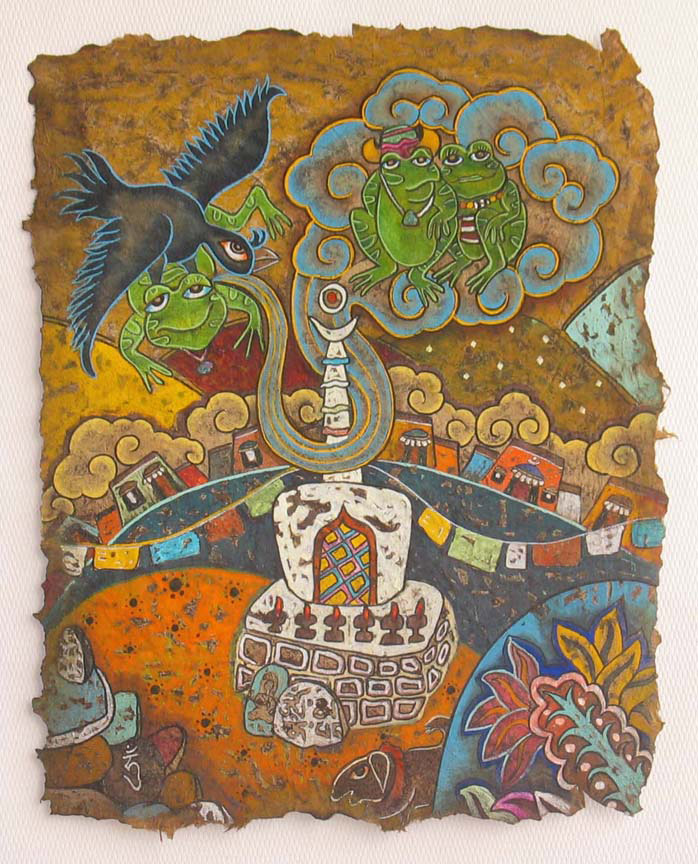

Tibetans indeed are adaptable, as are Tibetan frogs. Contemporary Tibetan painter Dedron tells us how a defenceless yet clever Tibetan frog outwits a ravenous crow. It’s a classic. Maybe the resourceful drogpa frogs on the outskirts of Gormo will yet outwit the central planners and petrochemical factories, and somehow hop home? Maybe they will grow their powers by first making it rain in their new desert home, recalling an old Hindu ritual Tibetans learned way back:

“Tantric techniques for controlling the weather are nothing unusual in the Tibetan tradition: weather-makers were even employed by the Lhasa government to ensure rain at appropriate times and to keep hail off vulnerable sites. The technique used by the senior lama of Tshognam, however, does not belong to the usual Tibetan repertoire but was assimilated by his grandfather, “Doctor Dandy,” from the “outsiders’ religion” (Tib. phyi pa’i chos) — specifically, from Hinduism: he learned it, it is said, from a mendicant Indian pilgrim. The ritual is performed in the summer, with the intention of ensuring that the pastures are well watered and that the snow-melt that irrigates the buckwheat crop is supplemented with rain.

“Two hollow wax models of frogs are made. Through a hole in the back, the frogs are filled with various ingredients, including the excrement of a black dog and magical formulae written on slips of paper, and the holes are sealed with a wax lid. One of the frogs is stuffed into the mouth of one of the springs to the east of Te, and the other is burned at a three-way crossroads. The principle of this method is apparently to pollute the subterranean serpent-spirits and the sky gods, and induce them to wash away the contagion by producing water from the earth and the heavens.”[6]

*********************************************************************

Will the frog outwit the big state crow? What are the inner

strengths of the traditional Tibetan drogpa

mode of production, living off uncertainty? Will the green iron rice bowl

prevail, a victory of suburban certainty over open range risk taking? These are the issues explored in the third

blog in this series of three.

[1] Du Fachun 杜发春, Sanjiangyuan Ecological Immigration Research, 三江源生态移民研究BeiJing : China Social Sciences Press, 杜发春著2014

Zhou Huakun; Zhao Xinquan ;Zhang Chaoyuan;Xing Xiaofang;Zhu Baowen; Du Fachun, 周华坤;赵新全;张超远;邢小方;朱宝文;杜发春,The Dilemma and Sustainable Development Strategy of Ecological Immigrants in the Three Rivers Source Area, China三江源区生态移民的困境与可持续发展策略Population.Resources and Environment, 2010 中国人口资源与环境

[2] Fachun Du, Ecological Resettlement Of Tibetan Herders In The Sanjiangyuan: A Case Study In Madoi County Of Qinghai, Nomadic Peoples, volume 16, issue 1, 2012: 116–133

[3] Du Fachun, Cao Qian, 杜发春 曹谦 Ecological Animal Husbandry: The Trend of Economic Development of Animal Husbandry in the Western Grassland, 生态畜牧业:西部草原畜牧业经济发展的走向 Original Ecological Ethnic Culture Journal 2012, 4 (01): 118-127 原生态民族文化学刊 2012, 4 (01): 118-127

[4] Du Fachun 杜发春, A Review of Western Academic Ecological Emigration Studies 国外生态移民研究述评, Ethno-National Studies 民族研究, 2014, (02): 109-120

[5] Li Runjie and the indissoluble bond of water, Qinghai Scitech Weekly 28 Nov 2018

[6] Charles Ramble, Navel of the Demoness: Tibetan Buddhism and Civil Religion in Highland Nepal, Oxford University Press, 2008, 174