INTO THE CANYON

ENERGIES OF LANDS BEING BORN

Chasing the putative mega hydro dam supposedly due for construction in the remotest corner of the Tibetan Plateau, we (and China’s busy tunnellers) find ourselves in landscapes of extraordinary energy, within an axial pivot of explosively highly pressurised rock, as subterranean worlds are reborn anew.

As below, so above: in these Tibetan lands of maximum energy, the mountains and skies are also highly energetic.

The mountains are rainmakers, drivers of both the Indian monsoon and the West Pacific monsoon, clothing this pivot of Asia in cloud, mist, torrential downpours, snow and glaciers. This is as far from the Equator as the tropics ever get, a massive biodiversity hotpot with almost no redlined protected areas to warn meddlesome visionaries to curb their enthusiasms.

The Eastern Himalaya Syntaxis and the orogenous uplift zone eastward, beyond, remain obscure, yet all that lives there rejoices in habitats from tropical to alpine as you climb out of the Brahmaputra, (or Salween, Mekong or Yangtze gorges) up to the glaciers capping the ranges, trekking as you climb through rhododendron forest, fir and spruce forests The profusion of life incudes snakes, leeches, mosquitoes, parasites and scattered villages perched above streambeds. All the more reason to gaze from afar, unless you are a visionary.

MUTUALLY INVISIBLE VISIONARIES

Those visions cluster into two schools, so far apart they are not only polar opposed, they are invisible, incomprehensible to the other.

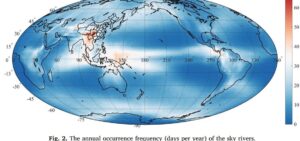

One group of visionaries is the geologists and hydro dam designers of Chinese modernity. Maoist China called them the guerilla fighters of socialist construction. Their vision is extractivist, reductionist, quantitative, classifying entire landscapes as energy flows, natural capital valuations, assigning numbers to sky rivers and the downward tug of gravity.

They tell a compelling story of why everything in nature should be classified as an asset class, in a world where money is all that matters:

What emerges from their calculations is the deeply incised Tibetan Plateau as a factor of production, especially the kinetic energy of a great river as it rushes down towards the floodplains of India. Having isolated an enumerated those kinetic energies, they become available to be made into electricity, exported thousands of kilometres to distant factories, via ultra-high voltage power grids.

This is the vision of high modernity mastering nature; yet today’s China has moved on from mega dams, mega projects, massive infrastructure that often fails to deliver what the vision promises. Constructing the biggest hydro dam the world has ever seen, in the Yarlung Tsangpo Great Bend syntaxis is a curiously old fashioned vision in a China no longer commanded by Politburo engineers, now by tech entrepreneurs whose mission is to stimulate new desires, new demand, new high quality development.

VISIONS OF PROTECTION

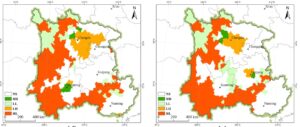

China today ignores the scientific teamwork of 20 years ago, which brought together leading Chinese and American biodiversity scientists to map these lands and their richly flourishing life. Those collaborations are long gone. We may be amazed to learn that only two decades ago Peking University, Birdlife International, Sichuan Forest Academy, Institute of Zoology – Chinese Academy of Science, Chengdu Institute of Biology – Chinese Academy of Science, Sichuan University, Xihua Normal University, Harvard University, Sichuan Forest Department, The Nature Conservancy all worked together to document the great biodiversity “hotspot” that is most of Kham, the medicine mountains of eastern Tibet.[1]

This was the Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund, created by the NGO Conservation International, in the earliest 21st century years, when Chinese and American researchers cooperated closely to rescue Kham from obscurity. By 2008 it was all shut down, and securitisation took command. Prior to the 2008 Tibetan uprising, China’s security state was already rapidly terminating this program and its visionary aspect, cancelling CEPF elevating Tibetan communities as active partners.

Now it is as if these partnerships of local Tibetan communities, Chinese scientific research institutions and international NGOs never happened. Yet “The rich cultural traditions and the Buddhist faith of the Tibetan people emphasize reverence toward life and nature. Traditionally, each Tibetan village and monastery designated its own sacred sites near mountains, forests, lakes and rivers where wildlife and habitats were protected. This system has always encouraged a harmonious relationship between humans and their surrounding environments, and serves as a particularly helpful cultural feature in support of biodiversity conservation and sustainable community development in this biodiversity hotspot.

“However, the Chinese government and outside experts usually make such decisions, which perpetuates the situation of local communities being excluded from important decisions that directly affect them and their natural resources. Since 2002, Conservation International (CI) has worked with local partners and stakeholders in the Tibetan lands to promote community-based conservation and livelihood development in the Mountains of Southwest China Hotspot.

“CI aims to revitalize the Tibetan cultural values for sacred lands as an effective measure for creating and expanding the number of community-based protected areas for conservation as well as a value basis for local sustainable development. In 2004, the Blue Moon Fund provided a one-year grant that allowed CI to implement Phase I of this project, which included: 1) assessing the sacred lands system in Ganzi, Sichuan, and Yushu, Qinghai……Community Conservation Fund, an innovative method to support community conservation initiatives, has been set up. 27 grants were made to pilot communities wide-spread in Sichuan, Qinghai and Yunnan, covering 80% the area of the SW China biodiversity hotspot. A community conservation model and network is preliminarily established. The network does not only include the communities’ elites who are playing fundamental roles in front line conservation but also the conservationists from NGOs, research institutions or even government agencies, who are providing technical, scientific, and legal back up for the community protection activities. The tremendous grassroots knowledge of indigenous approaches, folk tales, or even traditional customs of conservation have been collected and preserved through the project.

“The Community Conservation Fund got the funding from the EU-China Biodiversity Project, which aims to scale up the outcomes of the small grant project. Over 80 community small grants with clear biodiversity conservation outputs will be made in the ECBP project covering over 10 KBAs in Sichuan and Qinghai. Policy, legislation, and government recognition of community conservation will be better promoted under the ECBP project as an objective of CCF in the next 2-3 project period.”[2]

UNPROTECTED

There had been hope that much of this unique region would be given protected status, part of UNESCO World Heritage. IUCN – The World Conservation Union (Asia Program), UNESCO, United Nations Foundation (UNF), Conservation International (CI), The Nature Conservancy (TNC), World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), Fauna and Flora International (FFI), Ministry of Construction (MOC), Chinese Academy of Sciences, and the China Landscape and Historic Sites Association (CLHSA) all worked together, staging forums in Beijing in 2004 to promote World Heritage recognition.[3]

The abrupt cancellation of these collegial efforts, shut down completely in 2008, erased not only international cooperation but also awareness of the axial region as special, meriting protection. From then on extractivism returned as the dominant ideology, to be dammed. When China did eventually launch a “system” of national parks, most were in the pastoral landscapes to the north, while the axial pivot remains unprotected.

RECOVERING ECOSYSTEMS AFTER PILLAGE

Also erased, and by now forgotten, was the vision uniting this gathering of global institutions, national governments and NGOs, of ecosystem recovery, following decades of pillage. When the Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund got going, in 2001, it was only three years since decades of indiscriminate logging of the old-growth forests of Kham finally ceased, by decree, 1998. It was only one year since China joined the World Trade Organisation and its embrace of a global rules-based order, which China was keen to participate in. Transnational cooperation to mend rapaciously exploited ecosystems was the new normal, a new vision.

An early report from CEPF, in 2002 states: “Forest ecosystems in the region were under intense pressure from commercial harvest by state run enterprises from the early 1950s until a national logging ban took effect in 1998, limiting logging to subsistence needs of local communities. In the 1950s, Western Sichuan was reported to have a natural forest cover of 9.8 million hectares. By the 1990s, overharvesting had reduced the natural forest cover to 2.4 million hectares, a 76 percent decrease.

“State forestry management laws and regulations have traditionally prescribed a “quota management” system. In principle, such a system requires sustainable resource use by stipulating that annual timber harvests should be less than annual forest growth. In practice, however, the quota management system had been consistently overwhelmed by political events or development pressure.

“When timber markets were opened in the 1990s, no strong management mechanism was in place to properly deal with market-driven overharvesting by logging companies owned by different levels of government and by the communities that were involved as contractors and labourers. At the same time, forest users did not pay sufficient attention to replanting in state-owned and collective forests. Compounding management problems, forest inventory statistics are often inaccurate, resulting in logging quotas well above annual growth increments. The resulting overharvests, combined with land conversion for agriculture, were the main causes for the loss of 85 percent of old-growth forest cover along the Upper Yangtze during this period.”[4]

To suggest China made a mistake by indiscriminately logging the Chushi Gangdrug forests would today be classified as historical nihilism, the serious offence of alleging CCP rule has included mistakes. So this brief decade of flourishing of global focus on ecosystem recovery and protection now never happened, is never mentioned, not even by the NGOs involved.

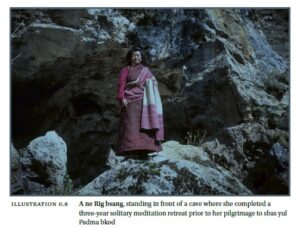

A REFUGE IN EXTREME TIMES

China now similarly ignores Tibetan pilgrims trekking to the lands designated for hydropower mega damming, ignores all Tibetan guidebooks to these hidden lands. Yet Pemakȏ, in the Yarlung Tsangpo Great Bend has, over many centuries, been a special geography of refuge and awakening, for many terton treasure finders, and many pilgrims. Similarly, the first account of Pemakȏ in a European language was in 1907: “Jacques Bacot’s account of the hidden land of Padma bkod in southern Tibet, in his Le Tibet Révolté: Vers Népémakö, La Terre Promise des Tibétains. Bacot was travelling in southern and eastern Tibet in 1907, at the time of Zhao Erfeng’s invasion, notorious for its brutality and destructiveness, and this was indeed a time when people were seeking to escape from a situation of conflict and destruction.”[5]

China has also chosen to forget similar traditions in China, right back to 5th century: “The theme of the hidden land is very close to that of the ‘heaven-caves’ (tung t’ien) of Chinese Taoist literature. Esoteric places where the initiation of the adepts took place, places of retreat for the Immortals, the‘heaven-caves’ like the hidden lands, represent a magic world, perfect and beyond the ordinary reality of the senses. In the Tale of the Peach-Flowers by T’ao Yuan (365–427) the site of the peach-trees is described as a world of Immortals, a place of happiness, a refuge which gives long life, outside time, to be found in the Hu-nan. There is also another place known as the Spring of the Peach-trees, to be found in the Ho-nan and which is also described as a place of retreat in times of trouble.”[6]

SEVERANCE

What Dudjom Lingpa composed was a practical, transformative method for facing imminent danger, that wholly frees the mind from fear by experiencing an unconditional willingness to surrender the body and die. Far from girding for combat, defeating the enemy violently, all enemies, both outer and inner, are defeated by developing unconditional willingness to offer the body to predators. Far from announcing a secret place of salvation, he turns our gaze to abandon all hopes and fears, all projections, to abandon the privileged self, to sever decisively all attachments.

Dudjom Lingpa and his immediate successors, inspired by immersion in the Pemako pure land of the Great Bend, wrote manuals for the intensive practices that transform the mind, for utterly letting go of all past regrets and future fears, freeing the mind to discover freedom, the abiding freedom from which all mental clutter, fear, hopes, expectations, habits and perceptions then arise.

They sought to persuade us that enemies, whether external or internal self-reinforcing subconscious chatter, come and go without any need of strenuous effort, to defend or attack.

How did the Yarlung Tsangpo Great Bend become the heart of these practices? “The great lama who acted as the vital link between Dudjom incarnations was Dza Pukhung Gyurmé Ngedön Wangpo. In accord with Dudjom Lingpa’s final testament and secret prophecies, Gyurmé Ngedön Wangpo went to Pemakö in Southern Tibet when his teacher passed away. He taught extensively throughout that region. There in Pemakö, as Dudjom Lingpa himself predicted, this superb disciple once again met his teacher, discovering Dudjom Lingpa’s immediate rebirth in a young boy who became known as Dudjom Rinpoche Jikdral Yeshe Dorjé (1904–1987). Every lineage that converged in Gyurmé Ngedön Wangpo was passed on flawlessly to the reincarnation of his teacher. By serving this supreme master through two incarnations, he guaranteed the seamless continuation of the Dudjom lineage into the modern world.”[7]

CLARITY OF VISION

So we plunge into these two visions: compare and contrast.

One cohort of visionaries seems to take for granted that rivers, mountainscapes are actually existing material realities to be measured, atomised, reduced to energy flows, quantified; engineered, all of which are real and objective categories, thus enabling carefully strategized extraction of specific flows. They would call themselves realists, not visionaries bewitched by abstractions they invented and are then enslaved by their fetishes. They are masters of the real world. In Buddhist terms they ae eternalists: materialists in thrall to their own inventions.

The other visionaries are not polar opposites, which to Buddhists would signify nihilism, denying there is any reality, that all is subjective. Their purpose is not to subvert materialism, but all -isms, all concepts invented by mind and then assigned objective status.

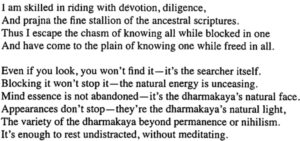

Actually, their work is to demolish all mental fabrications, of all kinds, whether my personal story of who and why I am as I am, or grand narratives, ideologies, missions. Their visions in place, in remote landscapes, are not inscriptions accreting new layers of meaning, adding to complexity. Instead they are radical deconstructions of any and all fixations, whether located in past, present or future, whether about the self or the world, revealed as mere assumptions that bind us to ongoing confusion and suffering.

This is not at all new, in the songs of the lamas, all the way back to Milarepa, and even earlier, to the mahasiddhas. Popular Tibetan songs of the most famous teachers of many centuries all point to this spontaneous awakening. Exhorting all who can hear to drop their habits, assumptions, anticipations, fears, plans, grudges, resentments, attachments, values, all of them as they keep you circling in confusion with no clarity as to the power of a free, uncluttered mind.

Freedom is the purpose, not adding to clutter in an already cluttered mind. The purpose of immersing in unfamiliar lands is remote landscapes is not to proclaim them as salvific, with some special power to liberate the mind, or to defeat enemies within or without. Reifying these beyul hidden lands is not the point. The shapes you encounter on the trail are mirrors, held up so you recognise the nature of reality, the nature of mind, and are spontaneously free. Such realisation is available to anyone, anywhere, at any time, but our habitual thickly described story telling of our selves usually smothers the occasional glimpse of the freedom of mind; so an alternative is to hike into a pure land, on pilgrimage, open to all that arises, with the visionaries’ pilgrimage guidebook pointing to trail moments conducive to awakening.

Their visions are in no way fabulations, impositions, fanciful romantic ascriptions of even further layers of meaningfulness projected onto rock faces and waterfalls, as if some cryptic, hidden deeper reality is revealed unto them.

We should not assume they are romantics out to weave even more rhizomal connections, or embellish mundane reality with their lyrical poetry.

“Another important Tibetan term dealing with Tibetan perception is ngön sum (mngon sum), which can function as both a noun and an adverb. It can indicate “the way things are without any error” (‘khrul ba min pa’i dngos gnas), meaning something like “actual” or “real.” In a context where it is understood that humans often misunderstand the way things are, to say that sees ngön sum or in a ngön sum way (mngon sum du) is to say that they see directly, in actuality, or really. Relatedly, it can mean “right in front, without anything hidden” (lkog gyur min pa’I srid snod bcud thams cad dag pa’i zhing du snang ba ste sku dang ye shes kyi rol bar snang ba.thad ka), or in other words, “evident” or “manifest.” Again, this definition shows how ngön sum indicates reality without errors or obscuration. Finally, ngön sum translates the Sanskrit word pratyakṣa, a term which literally renders before or in front of (prati) the eyes (akṣa), but is generally translated as “direct perception”. As a technical term, it indicates one of the means of knowledge (anumāna in Sanskrit) recognized by Buddhist philosophers, and indicates a direct and nonconceptual awareness of some object. One can also find uses of ngön sum indicating perception of one’s own mind or yogic perception, but for the most part it refers to sense perception, and in particular sense perception as giving correct and unmediated knowledge of some object.”[8]

BEYUL: HIDDEN LANDS

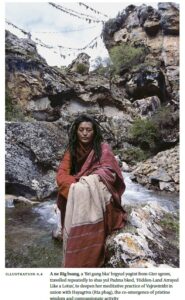

The special role of hidden lands is their capacity to cut through not only familiar habits, self-contrived constraints, but to deal decisively and instantly with all dangers, all enemies, all who would destroy. Pilgrimage into a pure land includes and accepts all the snakes, leeches, mosquitoes, landslides, not as heroic trials of endurance, but as mirrors just as are beautiful forests and waterfalls.

Hidden land pilgrimage is explicitly for destroying all enemies, subjective or objective makes no difference. It is a practice for degenerate times, when the malevolent craziness of the times closes in on you. It is in no way accidental that the most powerful pilgrimage guides were written in times of existential crisis, including the 17th century Dzungar Mongol army invasion of Tibet, the 1950s CCP PLA invasion of Tibet. Not only the pilgrimage guides of Dudjom Lingpa in the Yarlung Tsangpo Great Bend hidden land of Pemakȏ were lived, and then written in the extremes of 1959.

The same is true of Chogyam Trungpa’s 1959 Symphony of Great Bliss, written while fleeing the relentless PLA, a joyous song of total freedom, while on the lam:

‘

So it is little wonder that in our present degenerate times, filled with anger, blame, violence, confusion and incoherence, many now find these pilgrimage guides, their prayers and exercising of the power of imagination, to be useful on the streets of New York.

Walking a barely discernible trail in the mountains is in no way some alternative reality, an escape from danger into a paradise on earth. The entire purpose of pilgrimage is to defeat all enemies, from self-delusion through to People’s Liberation Army battle hardened shock troops out to machine gun you on sight. In short, the entry into the Pemakȏ hidden land is to decisively, definitively, irreversibly awaken to a deeply embodied experience of the nature of mind via encounter with the suchness of perceptual reality, once and for all. This goes further than mental decluttering or purification. This is an emergency measure for when the enemies press in, catastrophe is nearby.

It works because it is total, instantaneous and once wholly experienced, irreversible. It succeeds in transforming the mind, in the moment of maximum danger, by urging the pilgrim to wholly open the mind to the unknowable, ever changing fluidity of all phenomena, without and within, landscapes and thoughts, mountains and dreams, rivers and beliefs, flowers and judgements. [9]

It cuts delusions of all kinds, at the root. Nothing less will do when you are hunted by soldiers whose sole aim is to murder you. Only the invoked presence of the most wrathful of tantric deities has such power. We are the lands of Dorje Phagmo, dancing in her necklace of severed enemy heads. Urged on by the terton visionaries, we fully use the power of imagination to free the mind from all categories of the real and unreal, enemy and friend, fantasies and projections. The moment of imminent danger becomes abiding clarity.

HEROES OF SOCIALIST CONSTRUCTION, TERRIFIED OF TOUCHING TIBET

China is determined to make these lands Chinese, but the visionaries despatched to do the arduous, heroic struggle for hydro powered Sinicisation remain terrified of what they see, and worse, what might touch their bodies. As recently as 2006 a book The Yarlung Tsangpo Great Canyon: The last secret world, by historian and Xinhua reporter Zhang Jimin, was published in English by the official Foreign Languages Press. The entire book is a praise song to the heroic Han who have bravely penetrated Metok.

In a well illustrated book of 169 pages, Zhang has a long 27 pages chapter “Natural Disasters”, covering not only “really terrifying” landslides of “tremor-land”, avalanches, “primitive forests”, “the constant threat of mud-rock flows” but also eight pages on “blood-sucking leeches.”

Zhang is utterly horrified there is a creature that “punctures people’s skin and drinks their blood.”

So “in Lhasa the team members were supplied with white cloth knee socks” that not only failed, but showed up the blood, graphically photographed for the reader to see. “We walked in crouched positions with both hands crossed over our chests to avoid touching the plants and trees, because there were quite possibly dry-land leeches trying to bite passers-by. One had to go as quickly as possible so as to get through before the leeches had time to take action. When we walked on grass and open land we picked up our feet at every step and looked at each side. Our backs and feet were all pain, thanks to the countless bending and foot lifting.” (pp 147-151)

If this is visionary, it is hardly a vision of conquering nature and making the Yarlung Tsangpo Canyon Chinese; it is a vision of fear.

Fearless or fearful visions: take your pick.

CODA

China, at the highest level, is committed to assimilating Tibet into China, fears notwithstanding. Right now that means a huge struggle to tunnel a high speed railway across Tibet; tomorrow those massive TBM tunnel boring machines may be deployed to tunnel the Yarlung Tsangpo into the hydropower generating turbines.

So there is more to explore. As we track the tunnelers, we learn much more about the practical feasibility of a mega dam, since the rivers and rail routes are entwined. China is discovering, the hard way, that blasting and tunnelling Tibet is much harder than expected.

Next question: when is a mega dam not a dam at all, rather a river diverted into tunnels, with no dam required?

[1] Refining Conservation Outcomes for the Southwest China Hotspot, CEPF (Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund) Final Project Completion Report, Conservation International-China – 保护国际, February 28, 2007

[2] Small Grants in Supporting Integration of Science and Culture: Tibetan Sacred Land Protection and Conservation Effectiveness Measurement, CEPF Final Project Completion Report, 28 Feb 2007, Implementation Partners for this Project: Peking University, Green Khampa Association, Snowland Great River Association, Kawagebo Cultural Society

[3] Development of the China World Heritage Biodiversity Program, IUCN-The World Conservation Union Asia Program Project, CEPF Small Grant Final Project Completion Report, May 2005

[4] Ecosystem Profile Mountains of Southwest China Hotspot, Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund, 12 June 2002

[5] Geoffrey Samuel, Hidden Lands of Tibet in Myth and History, in Hidden Lands in Himalayan Myth and History; Transformations of sbas yul through Time, Frances Garrett, Elizabeth McDougal, Geoffrey Samuel eds, Brill, 2021, 52

[6] Giacomella Orofino “The Tibetan Myth of the Hidden Valley in the Visionary Geography of Nepal”. East and West, pp. 239-271. 1991, 239, note 1

[7] Traktung Dudjom Lingpa, A Clear Mirror the visionary autobiography of a Tibetan master, Rangjung Yeshe Publications,2011

[8] Catherine Anne Hartmann, To See a Mountain: Writing, Place, and Vision in Tibetan Pilgrimage Literature, Harvard PhD dissertation 2020, downloadable from https://dash.harvard.edu/entities/publication/9f9883e9-aa8c-4544-84a0-cfa71c683469

[9] Frances Garrett, Elizabeth McDougal, Geoffrey Samuel eds: Hidden Lands in Himalayan Myth and History: Transformations of sbas yul through Time, Brill, 2021