Blog five of five on an industry totally new to Tibet: mass manufacture of millions of alien trout in hydro dams on the Ma Chu/Yellow River

NORMAL FISH FOR NORMAL DEVELOPMENT IN NORMAL MARKETS OF URBAN MODERNITY

As the world (hopefully) emerges from pandemic, the landscape has changed, there is no return to the old “normal”. This is a moment that sharply questions China’s “normal” model for development of Tibet. In this moment, Tibetan insights into the nature of reality come to the fore, with renewed relevance, if we are to discover what is possible in the post-Covid world.

This case study of manufacturing millions of rainbow trout each year in a major Tibetan river, exemplifies all that is so yesterday about China’s development model for Tibet. China’s trout story was promoted as exemplary development of Tibetan resources, in this case the free public good of cold, fresh water impounded in dams China built across the Ma Chu/Huang He/Yellow River to generate electricity for the industrialisation of Tibet, and beyond.

In every way the trout industry ticked all the development boxes: making an unused stillwater resource productive; fully utilising the factor endowments -new and old- of Tibet; repositioning Tibet in China’s brand-conscious markets as a high quality, premium priced source of prestigious fish; teaching Tibetans the virtues of wealth accumulation; lifting Tibetan fish farm employees (if there are any) out of poverty; integrating Tibet into the wealthy urban Chinese consumer economy through a sophisticated cold commodity chain; demonstrating to backward, conservative, lazy Tibetans the virtues of capital accumulation to be invested in hi-tech enterprises for rich returns. It’s all good, a classic win-win.

It is all so yesterday. The “rules-based order” regulating the global trafficking of fish feed manufactured from dead fish; the global traffic in fertilised fish eggs flown in to Tibet from Scandinavia; the air freighting of chilled, filleted (or live) trout from Tibet to Shanghai, all used to be commendable achievements, proof of China’s sophistication and benevolent intentions towards Tibet. The rules-based order has faded away, not only because the virus snapped global assembly lines but because of trade wars and competitive economic nationalisms.

The old order struggles to return to “normal”, especially in China, where infected people were removed from society and isolated en masse, awaiting death or natural recovery. Now freight planes fly salmon from Norway to Shanghai, and return empty, traversing the whole of Eurasia with nothing on board. Is that normal?

If that is how we return to normal, driven solely by money, oblivious to the climate heating emissions of empty planes, we need a real restart. We need to reimagine what development means, what it is for, what its impacts are, not just today but in the longer term. To just go back to default settings would be blinkered, as if making money is all that matters.

A TIBETAN FRAMING OF MODERNITY

This is where classic Tibetan understandings of the phenomenal world come in. Far from being uncivilised, backward, feudal and ahistoric, Tibet offers the postCovid world a model of how to do development truly sustainably, over the long term, fully cognisant of consequences.

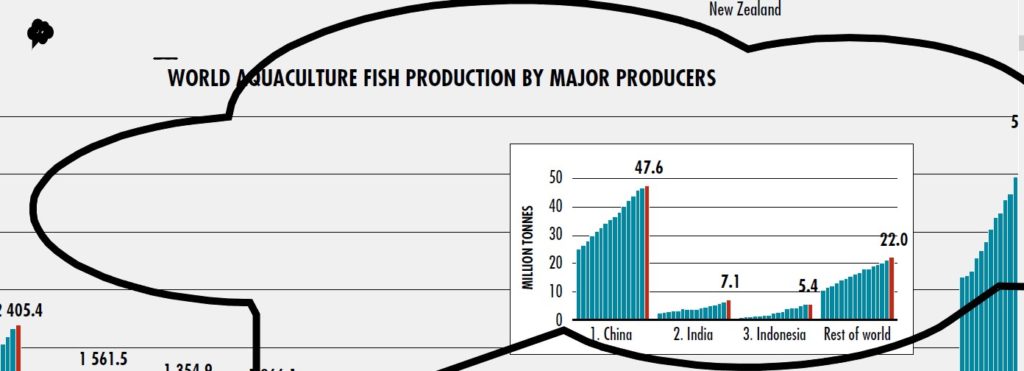

The routine plunder of planetary common pool resources was already at crisis point before the virus intervened. Treating the oceans of the world as free public goods, there for the taking, with no consequences, had long overfished every known fishery worldwide. The indiscriminate haul of any and all fish, scraping seabeds to capture all that lives, had already run out of cheap fish to kill, dry and grind into fishmeal to be fed to fashionable fish such as trout and salmon. Formulaic fish food manufacture was turning to vegetable sources of the nutrients farmed fish need, out of necessity as wild fish stocks were exhausted. China has long been the biggest exploiter of the world’s fish, its global fishing fleet making China the top predator of all.

Do Tibetans have anything to say in such circumstances, in today’s world? Tibetan civilisation values fish, in situ, at home in the water, frequently depicted as a sociable pair swimming together, the two golden fish, gaurmatsya in Sanskrit; གསེར་ཉ་ in Tibetan, pronounced sernya. This pair constitute one of the eight auspicious symbols, reproduced so often they may seem to be nothing more than sentimentality. Yet to Tibetans they symbolise fearlessness, specifically the resilient fearlessness of fully acknowledging all the uncertainties and dangers of living in a risky, contingent world. This is the fearless recognition that the root cause of death is birth, fearlessly facing whatever may arise. The inner strength of fluid acceptance of reality arises, giving rise to inner joy no longer dependent on desiring this and consuming that.

All that from a pair of fish. Little wonder it is a Tibetan custom to welcome a visiting lama by sprinkling white barley flour on the ground, in the shape of those fish, and the other auspicious symbols.

The best-known songs in Tibetan culture, the spontaneous songs of Milarepa and other mind training practitioners, take this awakening as their main theme. Thousands of gur and doha, many known by heart, urge ordinary folks to get over struggling, striving, planning and hoarding. The singers, emerging from their chosen lockdown solitude, sing to whoever has ears.

Some gur critique the passions of this time we now live in, so as to awaken their obverse:

“Stupidity’s senseless jokes are always increasing.

Primordial wisdom, do you dare dwell out there, asleep?

Desire’s actions are growing cruder.

Contemplations of the repulsive, which swamp did you fall into?

Anger’s brute force is always increasing.

Loving kindness, where have you fled?

Pride’s roaring is louder and louder.

Humility, are you deaf, or what?

Envy’s torments are grosser and grosser.

Pure perception, wherever you went, you did not penetrate to the root.”

That’s from the 17th century, by Kalden Gyatso, 1607-1677, not far from the Ma Chu/Yellow River and its trout farms.[1]

TOO MUCH YET NEVER ENOUGH

Meat and fish consumption in China have risen extraordinarily, yet it is never enough. China plans further intensification of factory farming of all edible species, in feedlot pens, in cages immersed in hydro dams. Intensification, for the sole purpose of feeding human greed, is the sole objective, despite the vague talk of green economy and ecological civilisation.

One consequence of the pandemic originating in China’s indiscriminate wet market jumble of captured species is the postponement of a global effort to get real about biodiversity. The UN Convention on Biodiversity (CBD) has, once a decade, a chance at setting targets that might, at last, make serious efforts to reverse the anthropocentric Anthropocene world made by the old normal. Everyone knows there is a wildlife crisis, in the seas, on the land, in the skies. Everyone values animals, even loves those which seem to exhibit human traits. Like climate change, the time for action is overdue.

The last time the world’s governments all got together to try to effectively halt wildlife extinctions was at the Conference of the Parties (COP) of the CBD in 2010. The result was the Aichi Targets, named after the Japanese city where the world assembled. Compared to the current situation, the Aichi targets were limited, something bolder is needed. The Aichi targets failed, and the world’s biodiversity conservationists are the first to say so.

The next opportunity to try again, to create a new normal agreed upon worldwide, was meant to happen at the next UN CBD COP, scheduled for 2020, in the Chinese city of Kunming. That had to be postponed, leaving the wildlife trafficking to China intact. Now, the CBD COP is rescheduled for 2021, still in Kunming. China was keen to be host, and the CBD was keen to accept, since, like most UN bodies, it has limited budgets and limited authority to set binding goals and then hold accountable the governments that sign onto them. Staging a CBD COP in Kunming was planned as a way for China to present itself as a champion of biodiversity conservation, complete with side trips for conference delegates to new national parks in Tibetan areas nearby, including the new Panda national park, which is mostly in Tibetan counties of the Sichuan mountains.

Then the virus struck, not only halting the global gathering, but also bluntly reminding the world that it originated as a zoonotic disease, jumping from wild animals to humans, due to China’s voracious trafficking in wild animals for human consumption. This has been a setback for China, and a reminder that we cannot go back to an old normal in which all governments make the right noises about wildlife, but little in practice is done whenever wildlife get in the way of making money. Will there be a CBD COP in 2021? Will it commit to real world goals to save wildlife? Will it still be held in Kunming? Will China allow the world’s conservation NGOs in, to do their advocacy work and hold governments accountable?

In today’s world there are plenty of folks whose response to the frailty, contingency, uncertainty and pandemic vulnerability is to seek, above all, to find out who can be blamed. From the US President down, the quest for blame consumes energy. The World Health Organisation, like the Convention on Biodiversity and the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change are weak, underfunded, unable to enforce anything, usually reduced to falling in line with the governments that finance them. This is true of all UN agencies. All of them are restricted by their donors and member states, who resist any international body having jurisdiction over them. The governments of the world, for all their talk of a “rules-based order” in practice prefer anarchy and, if you are big enough, bullying.

So, UN CBD Kunming 2021 may showcase China as champion of biodiversity, largely by rezoning much of Tibet as national park.

These are all instances of a world in denial, of lip service to lofty climate and wildlife goals which will not be delivered, a world in which little matters other than wealth accumulation, all else is external. That’s a world yearning to return to normal, having satisfyingly found who to blame.

POST PANDEMIC NORMALITY

Those less obsessed with blame nonetheless also yearn for normal, in which the economy one more takes precedence over everything else.

Yet a growing swell of thoughtful folks are telling us this virus is teaching us there is no going back to endless economic growth as an end in itself, which makes everything else secondary. The just-in-time globalised commodity chains, forever seeking to reduce labour costs and boost profits got us to the pandemic. Enough.

We emerge from lockdown changed, questioning the endless acceleration, intensification, urban densification, energy-intensive, capital-intensive global gig economy that concentrated wealth in a few hands, and made everyone else precarious, awaiting their job being automated by AI and algorithms. Efficiency has had its day, has sacrificed too many livelihoods, in its driven, disruptive insistence on finding hi-tech low wage solutions to problems we never knew we had.

The millions of trout made in Tibetan dams illustrate all of this. The plan is to intensify further and further. So where does the Tibetan take on reality come in?

Tibetan culture reminds us, for starters, that we are basically all the same, so privileging my pile of wealth over all others, human or animal, is plain foolish. Trusting wealth to make you happy is foolish. Forever deferring enjoyment because even more wealth generation is at hand is foolish. You can’t take it with you when you die. Human heartedness, the ability to recognize ourselves in others (and vice-versa) and forebear is essential. Patience, a wider perspective, knowing the difference between wants and needs: all are essential. Discovering inner sources of strength rather than the gratifications of consumption (followed by indifference or remorse); discovering immeasurable joy at simply being alive: all essential. Sufficiency matters more than efficiency.

These are among the strengths of Tibetan culture, not just because of the Buddhist teachings, but because they have been taken to heart, are embedded in daily life, can be observed at work in the lives of people you meet.

As the Dalai Lama has often said, all religions teach tolerance, love and patience. In Tibetan Buddhism these arise not as moral strictures, or dogmatic constraints on innate human selfishness, but as spontaneous experience of reality unadorned by overthinking. For Tibetans, working with whatever arises comes readily, not as disruption or threat, not as evil or good, just the constant arising of circumstances and perceptions in a contingent world dependent on causes and conditions. To behave morally is not to pledge an oath to a moral code that combats inherent sinfulness; it is a recognition that we are all alike, we all habitually wander repetitively, we all experience confusion and turmoil which get worse the more we expect control and predictability.

Modernity, development, urbanisation, intensification, densification, growth all demand control, aggressive risk management, constant measurement of variables, planning, critical path analysis and much more imposition of human will on wayward reality. Such tasks are endless and exhausting. We usually seem to have it all under control, in a seamless, interconnected, just-in-time delivery chain, then suddenly it all falls apart, as it did when a widely predicted pandemic arrived.

Many people, exhausted by the relentless accelerations and accumulations of modernity, are now seeking new paths. Some call it agro-ecology, or degrowth, rhizomatic networking, deep ecology, fungal futures, web of life, the great turning, subsistence affluence, bio-cultural diversity, it goes by many names, and struggles to be heard.

China frequently calls for establishing a harmonious coexistence model of man and nature in national parks with Chinese characteristics, but this cumbersome official phrase reveals tensions and contradictions. Having so sharply differentiated man from nature, also elevating human will above all else, the task of bringing these naturalised categories of man and nature back together is laborious, difficult, endless, elusive, made more so by the insistence on Chinese characteristics.

For Tibetans, this is not a struggle, nor a moral imperative. It arises spontaneously, not as a result of effort. Once insight into reality is realised, it is not forgotten; it is experiential, embedded in being alive. There is nothing romantic about this, or wishful fantasizing: it is a plain recognition of contingency and interconnectedness, once privileging of I over others is dropped.

Kälden Gyatso:

“Although the liberation-seeking bee of my mind

Longs to fly on the path of liberation,

I am attached to the feast of honey -the eight worldly concerns-

And to striving for personal gain and esteem.

Please teach me how to recognise

That sensory pleasures are deadly poisons.

Please grasp me with the iron hook of compassion.”

Trout farming the rivers of Tibet for the sensory pleasure of eating expensive, exotic fish should not be the new normal.

Reducing Tibet to a gourmet factory farm is not the way to development.

Better to leave the fish in the water, swimming sociably together, the abiding symbol of fearlessness.

[1] Victoria Sujata, Journey to Distant groves: Profound songs of the Tibetan siddha Kälden Gyatso, Vajra Books, Kathmandu, 2019, 53