At the end of 2024 an intensive scenario planning exercise on the future of Tibet was published. A hundred young exiled Tibetans gathered in several sessions to plot a wide range of scenarios for the year 2040, ahead far enough to be different, close enough to be imaginable.

The scenarios ranged widely from the most pessimistic – “Crushed Opportunity” and “Final Chapter” – to the most optimistic –“A New Hope”, with “Hanging in There” in between. Despite much classic Tibetan hopefulness, these scenarios tend to imagine fearsome advances by an unstoppable China. Sobering reading, which does not ignore weaknesses in exile Tibetan unity.

But is China unstoppable? Does Xi Jinping issue a decree, everyone salutes, and his command is implemented?

What if we attempted a similar scenario exercise, from a different angle, this time by diving deep into Chinese sources?

The authors of the Future of Tibet exercise generously invite further input: “We expect to contribute to a more open-minded, diverse and transparent discussion about our common possible futures.” In response to the pioneering exercise, initiated and achieved entirely by Tibetans, this blog -by a nonTibetan- explores likely Tibetan futures, clustered round two future dates deployed by China’s planners: 2035 and 2049.

Approaching the future of Tibet via China’s party-state plans has many limits. It says nothing at all about how Tibetans respond to China’s nation building; and we do know Tibetan civilisation withstood the onslaught of the Cultural Revolution, and in the 1980s and 1990s bounced back. We do know Tibetans are rapidly learning China’s laws, and also now a religious revival of inner transformation is strengthening resilience.

The 2024 Future of Tibet report focuses on resistance. Here the focus is only on China as top-down planner, struggling to invent ways of assimilating Tibet.

ACCELERATING ASSIMILATION

Our starting point is to assume China is in the middle of inventing a Tibet that is tangibly China’s, a mission still unfulfilled, that turns the alien rule of the conqueror into a unified nation-state with one single language, culture and identity shared by all. That is clearly China’s goal, a goal China says it has achieved with 54 of the 56 minority nationalities -120 million people- across China, with only the stubborn Tibetans and Uighurs holding out.

That explicit goal of complete assimilation is an invention of this century, a major policy shift away from China’s adoption of the Soviet model of regional autonomy for minority nationalities. The new goal demands more than begrudging compliance and performative declamation of CCP slogans. The demand is that Tibetans and Uighurs internalise and adopt a new identity, as members of the Zhonghua Chinese race, as their primary loyalty.

So ambitious is this goal, almost everything China does in Tibet can be seen as part of a coherent agenda, which combines push and pull, coercion and the attractions of urban wealth. Everything, from ruthless repression of protests, education and language policy, infrastructure construction, tourism planning, national parks, nomad displacements, frontier village construction, big data centres, extraction of minerals, hydro dams and massive solar arrays, can all be seen as aspects of a coherent plan to accelerate time, collapse space, collapse Tibetan identity and language into marginal irrelevance.

Although these policies cohere, their outcome is uncertain. China is trying to cross the river by feeling, stone by stone, for the next step towards the far shore of a unitary nation-state, no longer an unwilling empire under alien rule. In Xinjiang, China opted for extreme coercion, and in Tibet an open air prison. Neither is conducive to changing minds meaningfully.

In Xinjiang and even more so in Tibet the classic Chinese colonising strategy of shunting masses of desperately poor Han peasants into the new territories didn’t succeed. After decades of privileging Han emigrants to Xinjiang over the Uighurs, the marginalised revolted, and were crushed. In Tibet due to cryosphere cold, altitude and hypoxia, there was only limited population transfer of Han and Hui to lower altitudes, mostly in Amdo, few elsewhere.

With classic settler colonisation unworkable, and the Tibetans remaining uncooked, China has been searching for a strategy that, over decades, makes Tibet China’s. Whether that goal is achievable, by 2035 or by 2049, is what this post is about.

In 2020, at the Seventh Tibet Work Forum Xi Jinping -in instructions not made public- ordered intensive assimilation: “General Secretary Xi Jinping mentioned in his important speech at the seventh central government symposium on Tibet work that “excavating, collating and publicizing the historical facts of interactions and exchanges and intermingling of various ethnic groups in Tibet since ancient times, guiding people of all ethnic groups to see the direction and future of the nation, deeply understanding that the Chinese nation is a community of destiny, and promoting interactions and exchanges and intermingling of various ethnic groups.”

Those commands were later revealed by a Tibetan cadre loyal to the party-state, employed at Central University for Nationalities in Beijing. He is an example of assimilation in practice; in Chinese, he is called Xi Rao Nima 喜饶尼玛, in Tibetan Sherab Nyima.

Xi Jinping has demanded assimilation since 2014. Now there are textbooks 中华民族共同体概论which are compulsory reading for higher education students, and Communications University of China 中国传媒大学制has launched videos promoting the concept of one Zhonghua race, speaking one common language, aimed at younger students. So far the videos are very wordy: take a look.

The campaign to intensify assimilation is now gathering momentum. Now that there is one new core textbook, the “Introduction to the Chinese nation community” by top CCP ideologue Pan Yue, making a simplified Han history into everyone’s inevitable destination, the real work of a classic mass campaign is beginning. A lot of Han educators are finding the assimilation campaign provides them with an iron rice bowl for life: “We must tell the historical characteristics, cultural characteristics, and social characteristics of the Chinese nation community, and the facts and vivid stories of the long-standing civilization of the Chinese nation…., scientifically set up the curriculum system, compile general reading materials, establish case libraries, examination question banks, and student observation and internship bases; in particular, we must strengthen the construction of the team of young and middle-aged teachers, and drive young students to consciously become defenders, practitioners, and builders of the Chinese nation community…. How to get the “Introduction to the Chinese nation community” into colleges and universities, classrooms, and minds, educate the young generation and make them defenders, practitioners and builders of the Chinese nation community, requires effort.”

Will this push to assimilate succeed, by 2035 or 2049? Only Tibetans can answer that.

China is now in a hurry to complete the transformation of imperial alien rule into a single, unitary nation-state consciousness and identity, with a single language. The urgency arises for a CCP leadership elite obsessed with risk, seeing or foreseeing danger wherever they look.

Tibet in their eyes is not secured, not populated with politically compliant Han immigrants. The Tibetan Plateau is classified as ecological security barrier, but the Tibetans remain raw, uncooked, unconvinced China’s race to be rich is worth ditching the mother tongue and landscapes that provide all that is needful.

Tibetan prayers have always invoked “these degenerate times.” Now they are truly degenerate. The first action of President Trump was to close human rights funding. Initially, ever hopeful Tibetans assumed this was unintentional, a mistaken over reach. Not so. It turned out to be intentional. Greed, selfishness, the power of the powerful and forceful are back; and the elites of China and the US are more alike than ever.

China is deeply committed to achieving a future utopia based on global domination of manufacturing industry, even if that means ever greater use of electricity thus ever greater extraction from Tibet of lithium, copper, water, hydropower, sunshine and wind, all for use thousands of kilometres away in the world’s factory of coastal China. This is the compulsion that drives China to exploit Tibet, and shunt the Tibetans out of the way, into peripheral frontier villages, where they can be taught entry level into the Chinese economy.

Recognising China’s long term plans for the future of Tibet does matter; all the more so in degenerate times where greed and bullying rule.

Close to a century ago the great writer Thomas Mann wrote: “We know now that the idea of the future as a ‘better world’ was a fallacy of the doctrine of progress.”

However, knowing that these are indeed degenerate times, when all that is solid just vanishes, does not mean depression or despair. Tibet has lived through worse, especially the two decades up to and including the Cultural Revolution. We could recall that Khamtrul Rinpoche’s depiction of liberating reminders of the total freedom of the mind, imprinted in the rockfaces of the Yarlung Tsangpo gorge, were written at a time when he was fleeing the ruthless advanced of the PLA shock troops across Tibet We could remember that Chogyam Trungpa’s Symphony of Great Bliss was written while on the run from the PLA.

Facing the future, in deeply Tibetan ways, is so much more than grim resistance.

ONE DECADE AHEAD

2035 is now only 10 years away, close enough to readily assess current trends, Chinese policies, mass campaigns, compulsory slogans and Five-Year Plans to get some idea how China’s target year of 2035 might look.

2049, the centenary of the People’s Republic, is much harder to foresee, and Chinese planners tend to be vague, yet utopian, in their vision of what is to be achieved in Tibet and China by then.

If almost all aspects of China’s interventions in Tibet share a common goal, we may be able to extrapolate a range of outcome scenarios. What we don’t do here is assess the extent of Tibetan unity in the face of China’s drive to make all Tibetans scrutable, visible, compliant and loyal to Beijing.

What we can do is sketch China’s goals and plans to attain them. We could say China is trying to build a post-industrial Chinese Tibet; having failed, over several decades to industrialise: meat production communes, carpet factories, township and village enterprises, wool scours, walnut plantations. Almost all failed.

Extractive plunder did flourish in chromite mines of Lhoka, in magnesium and potassium extraction from Amdo Tsaidam Basin and later in the industrial processing zones radiating from Xining city. Intensifying Tibetan agricultural production largely failed. Thus population transfer in the 20th century largely failed.

Now China is feeling for a “high-quality” consumer-led future by mass domestic tourism to pristine landscapes largely devoid of Tibetan guardians, a post-industrial economy capable of employing large numbers of Han emigrants. In 2025 there is sufficient momentum to try to see ahead to 2035 and 2049.

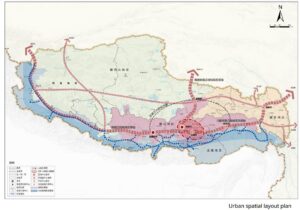

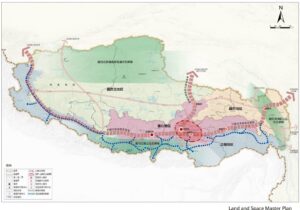

In the 21st century the economy and wealth creation rely on mass tourism and massive export of energy from Tibet, as well as sourcing of industrial raw materials -copper and lithium- from Tibet. This increasingly looks like an urbanised Tibet with rural districts depopulated and relocated to frontier villages, as the first steps in a civilising mission that reaches eventual fulfilment in full urbanisation, with most Tibetans in high rise apartment blocks by 2049.

This blog sketches what China has done in Tibet up to 2025, policy by policy, to see if it does add up to a coherent strategy aiming at attaining a consistent goal by 2035 or 2049. Usually we look at repression and human rights violations separately to the extraction economy. We usually look at frontier villages as a geopolitical move and not as also a step in a civilising mission headed towards eventual urbanisation. We look at hydro dams and demolished monasteries but not so much at Tibet as a major exporter of energy -hydro and solar- to the world’s factory on China’s distant coast. We look at mining as an environmental disaster, not so much as the start point of China-centric commodity chains and Tibet’s place as a cheap supplier of raw materials.

In short, we seldom look at Tibet as an economy, yet once we do the dots all join, and we discover how China is transforming Tibet into a modern economy, a colony that is transitioning from cost centre to profit centre, increasingly paying its way by provisioning China with copper, lithium, electricity, water and landscapes suitable for mass tourism; all now connected by transport links that reposition Tibet much closer to China. Tibet is being locked in to China. All those billions spent on highways, tollways, railways, highspeed electrified rail, power grids, urban construction, red meat and aquacultured fish cold chains, all add up to an economy, with Chinese characteristics.

TIBET AS A MASS HAN TOURISM DESTINATION

At the end of 2024 Lhasa became a spoke in the hub-and-spokes model of international airline strategy. Officially, the population of Lhasa is under half a million, yet “the city received nearly 37.6 million tourists in 2023, up 60.87 percent compared to 2019.” Even in the wintry first months of 2024 “the city received 3.5 million domestic and foreign tourists, an increase of 87.6 percent year-on-year.”

A state-owned airline based in Chongqing now flies several times a week between Lhasa and Singapore, Lhasa and Hong Kong, with Chongqing the hub.  Not only does this bring more tourists, but it is also the creation of Tibet as an investable asset for distant corporations expanding into fourth tier cities, keen to be first movers in establishing their brands, ahead of competitors. Lhasa has a Marriott StRegis hotel and an InterContinental next door to Gurtsa prison.

Not only does this bring more tourists, but it is also the creation of Tibet as an investable asset for distant corporations expanding into fourth tier cities, keen to be first movers in establishing their brands, ahead of competitors. Lhasa has a Marriott StRegis hotel and an InterContinental next door to Gurtsa prison.

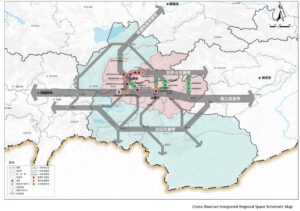

It has a train station that mimics the silhouette of the Potala with high-speed trains to Nyingtri and, by 2030, all the way to Chengdu and China’s entire high speed rail network, the world’s biggest.

If Lhasa currently receives almost 40 million tourist arrivals a year now, by 2035, with the Chengdu to Lhasa route scheduled to take only 14 hours of pressurised luxury, the total could double. Then there are the newly rich of India, doing Tibet, a consumable greater Hindutva. Can Lhasa handle 40 million tourists, nearly all domestic Han, now? Can it handle 80 million by 2035?

Only now is the infrastructure rapidly nearing completion, which turns TAR into a circuit of destinations. It was back in 1990 that UN World Tourism Organisation commissioned a Hong Kong consultancy to propose that TAR tourism circuit.

Tourism is a labour-intensive industry: meet & greet transfer, room service, bar staff, maids, cleaners, tour guides etc. Ideal for attracting Han immigrants, and Tibetans schooled in fluent Chinese as gig workers in the new economy.

By 2035 new regional airports will be operational, relieving Lhasa of being the sole destination. New airports at Mt Kailash, Nagchu, Nyingtri, Mt Everest base etc enable a tour circuit, with each branded as a unique destination.

Then there is the fast-growing urban Han market for exotic getaways featuring quaint ethnic customs dress and cuisine, to take a break from the intense competitiveness of the big Chinese cities. Now that the ethnic destinations of Dali and Lijiang, at the foot of the Tibetan Plateau, are overrun by Han, there is a new expressway and fast rail to Dechen Shangrila only 90 minutes away. Eastern Tibet is colonised by waves of hip entrepreneurs piloting chill and funky resorts, soon overrun by mass tourism, and the gentrification wave moves on the next remote village. This is Tibet as a consumable, an economy based on spectacle.

Right now Chongqing is the hub, Lhasa a spoke, with visa free international arrival in Chongqing, fast emerging as the capital of all of western China. Just look at a famous Thai influencer enthusing about the pleasures of Chongqing. In future Lhasa will also become a hub, its spokes radiating out in all directions as the tour circuit takes shape.

By 2035 a ski resort in Tibet is likely, as it is party-state policy to encourage snow sports and resorts.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QFG0P-7_0As

Even Tibet’s glaciers are now assessed as potential tourism destinations. As for 2049, China’s plans are vague. Intensifying tourism has been a high priority for a long time, named in one Five-Year Plan after another as a “pillar industry.”

In reality remaking Tibet into an asset, a profit centre with Chinese characteristics, capable of employing many Han, and maybe displaced Tibetans doing menial hospitality work, is taking decades. But it now looks like 2035 will be when it all comes together, including a mass market yearning to holiday in Tibet, China’s crown jewel.

What will be the role of Tibetans, beyond hospitality gig work? Tour guiding requires fluency in standard Chinese, with exam and licensing required. Han love cosplaying as Tibetans. Han tourists are rapidly discovering Tibetans are nice people, and romantic consumption of Tibet means having a few Tibetans around, to handle the yak you sit on for a selfie, or to line up a mastiff to pose with, or do that incomprehensible prostration thing Tibetans do while you film them.

China’s “well-known and widely liked rural nostalgia videos become framed as part of the ongoing rural development campaign promoting a new appreciation of the countryside and rural traditions, as well as a place of economic opportunities inviting the move of young educated urbanites, as well as the migrant population to return to the villages. In this “platformization of politics”, commercial platforms and government actors seem to work hand in hand in steering rural video production and dissemination towards both commercially and politically exploitable representations of the countryside.” https://www.worldmaking-china.org/en/aktuelles/ASC_2023.html

RURAL TIBET

In the enormous size of the Tibetan Plateau, its scattered population of livestock herders makes a sustainable living by mobile, extensive land use, always moving on, to protect the grassland. The weather is highly variable, snowstorms even in summer. Tibetan nomad livelihoods thrived not despite uncertainty but because of it, and nomad adaptability. China has never understood this.

China’s priority is to depopulate the rangelands, relocating the displaced to newly built prefabricated frontier villages and to urban apartment towers, where keeping animals is forbidden, and all inherited skills are redundant. This reduces the displaced to dependence on the party-state as benefactor who hands out transfer payment rations. Fit young adults capable of energetic exertion at high altitudes are required to patrol frontier districts, on advance security risk prevention monitoring. Very few Han can be energetic at high altitude.

Many of China’s policies, with seemingly varied purposes, all disempower, demobilise and displace rural Tibetans from their pastures, and land rights. In the name of productivity, carrying capacity, stocking rate regulation, household responsibility, land degradation repair, biodiversity conservation, watershed protection etc, nomads are removed, usually hundreds of kilometres away, their land rights and livelihoods cancelled.

Rural Tibetans, many still on their own lands, or shipped off to frontier villages, continue to face sharp restrictions on mobility, especially pilgrimage to Lhasa and the blessings of being in the presence of the Potala. While Han mass tourism accelerates, China remains fearful of Tibetans gathering as crowds, and making pilgrimage -measuring the earth with your prostrating body- is almost forbidden.

Han China’s foundational assumption, whether in 1949 or now, is that Tibetans had all that land, and did so little with it. Clearly unproductive, just wandering aimlessly, following the animals. Logically it is better to clear the land of ignorant rural labourers who degrade the grasslands, and start over, with a new economy, of intensified agribusiness cattle feedlots and slaughterhouses, the pastures aggregated into industrial scale, easily done once the people are removed.

Human Rights Watch, in a carefully tabulated 2024 report, calculates that 3.36 million rural Tibetans have been relocated, in this century, some still on their customary winter pastures, many displaced to distant new towns. The programs justifying displacement are ongoing. By 2035 we could expect most of rural Tibet to be depopulated, even if Tibetans are refused urban hukou residential status in the fast-growing cities. By 2049, if assimilation is seen as successful, those who were displaced to new frontier villages, and the new generation educated in Chinese schools to identify as Zhonghua, may be permitted to resettle yet again, in cities, primarily Xining and Lhasa, also fast growing cities such as Shigatse, Chamdo, Nyingtri and Yushu.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aqItwkOXgkU

By 2049, if China assesses a generation an d more of assimilation programs to have succeeded, Tibetans will be allowed to emigrate to cities, and transfer household registration, becoming one of many minorities scattered throughout the city mix.

Depopulation of rural Tibet has a destination in mind, with todays’ semi urban, semi-rural relocations an intermediate step towards the eventual goal of full urbanisation, the fulfilment of Chia’s civilising mission, the great achievement of a century of turning an empire into a unitary nation-state, ruled forever by a single party.

Whether this is achievable depends on the inner strengths of Tibetans to maintain culture and language transmission. But there can be no doubt full assimilation and city life are China’s 2049 goals.

INDUSTRIALISATION

By 2035 Amdo is highly industrialised, in a belt stretching from the salt lakes of the Tsaidam Basin all the way east to Xining and Gansu.

The drivers of this heavy industrialisation are many, pressing in from all directions: raw and semi processed minerals extracted from central Tibet but smelted in Amdo/Qinghai; photovoltaic solar panels relocated from factories that used to be in Xinjiang; largescale animal feedlots fattening yaks trucked from Golok, for slaughter and cold chain packing; heavy industries moving deep inland from the coast, incentivised by Beijing subsidies to go west. Many more, manufacturing chemical fertilisers, plastics, aluminium, bitcoin, lithium batteries. The merging of two cities into one megapolis, stretching 200 kilometres from Lanzhou to Xining, is well under way.

By 2025 much of this is already happening, held back by tech chokepoints restricting lithium purification from the massive deposits of the salt lakes near Gormo. A likely scenario: by 2035 those restraints are overcome, electric car demand booms, China aims at self-sufficiency rather than rely on lithium from Chile shipped right across the Pacific, vulnerable to American interdiction. Tibet is plundered.

In 2025 a cascade of 11 dams in succession, repeatedly interrupting the Ma Chu/Yellow River already generate so much electricity for industrial use much is exported to far distant provinces. By 2035, as the Lanxi (Lanzhou-Xining) megapolis fills with industrial “parks”, the massive output -solar and hydro- from Qinghai is needed for local industries. In 2035 the world congratulates China on having achieved a full-scale green energy economy in Amdo/Qinghai, even though this means ongoing intensive industrialisation. Only by 2049 does the world realise China’s green energy leadership and industrial revolution dominance of nearly all industries is contradicts claims to “ecological civilisation” and incompatible with reducing actual climate heating emissions.

CLIMATE

By 2035, as the world continues to heat, and the Tibetan Plateau heats faster than global average, the 60% of the plateau in the grip of permafrost is melting. As ice in the soil melts away, thousands of years of grass, shrub and tree roots in the soil are exposed to air, rotting microbially, emitting methane, a climate heating gas 80 times more potent than carbon dioxide.

Hydropower generated on Tibet’s major rivers becomes unreliable, lakes spill, glaciers collapse, landslides and debris flows intensify, rivers are blocked and then burst out. Wetlands dry as ice recedes.

By 2049 the monsoons coming towards Tibet from both the Indian Ocean and Pacific Ocean weaken further, and become more extreme and erratic, while westerly winds and their western “disturbances” grow stronger. Lakes in northern Tibet overspill.

Floods and droughts in China intensify, and Chinese efforts to geoengineer more rain over Tibet fail. Jetstream winds above the plateau weaken and wander, flipping unpredictably between skirting below the Himalayas in winter, and diverting to far northern Tibet in summer. As a result in some years the Indian Monsoon and/or the East Asian Monsoon completely fail to arrive onshore.

WHY 2035 AND 2049?

2035 is now close and is more defined. Two Five-Year Plans, China’s 15th and 16th, get us to 2035. In July 2024, the Communique of the Third Plenary Session of the 20th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China announced:

“By 2035, we will have finished building a high-standard socialist market economy in all respects, further improved the system of socialism with Chinese characteristics, generally modernized our system and capacity for governance, and basically realized socialist modernization. All of this will lay a solid foundation for building China into a great modern socialist country in all respects by the middle of this century.” https://english.news.cn/20240718/e74d931886e64878ae6e5419d19a64da/c.html

“In the 19th Congress Report, Xi revised his 2012 formulation of the China Dream. He replaced “country” with “great power.” He outlined two distinct phases, 15 years each, to divide the 30- year duration from 2020 to 2050. He said the Party would ensure that “socialist modernization is basically realized” in the first stage (2020– 35), and, on that basis, complete the process of building China into a “great modern socialist country that is rich, strong, democratic, cultured, harmonious, and beautiful” by 2050.

“He also specified six indicators for the “basic realization of socialist modernization” by 2035, in the order of:

- Greatly enhancing China’s economic and technological strengths, and making China a top- ranked innovative country.

- A comprehensive improvement of institutions, and finishing off the modernization of state governance system and capacity.

- Pushing to new heights the cultured level of society, and greatly enhancing China’s cultural soft power. The influence of Chinese culture has been broadened, widened, and deepened.

- Getting people to live more comfortably, and enabling the entire population to make solid progress to achieve common prosperity. This means significantly increasing the ratio of middle- income groups in the population, greatly reducing the disparities in urban– rural development, regional development, and living standard generally, and making access to basic public services more equitable.

- Completing a modern social governance layout, and making the society full of vitality, harmonious, and orderly.

- His ultimate vision is to make China a “great modern socialist country that is rich, strong, democratic, cultured, harmonious, and beautiful” by 2050.”[1]

Hu Angang, one of the principal architects of China’s policy of rapidly assimilating all minorities, amplifies: “The moral quality of China’s citizens will be improved in all respects. Observing core socialist values will become a conscious action of the whole society, national moral standard will be significantly improved, and the Chinese spirit, values, and strength will become important influences and driving forces of China’s development. China will become a global leader in terms of international influence. The overall strength, international influence, and soft power of Chinese culture will increase.”[2]

If you promise the masses a utopia, it should be well into the future, not something you find yourself accountable for any time soon.

“The journey that began in 1949 shall end in 2049. China’s communist leaders identify this centenary as the date by which China will officially have become a “great modern socialist country in all respects” [全面社会主义现代化强国] that sets an example of “prosperity, strength, democracy, advanced culture, social harmony, and beauty” for the entire world.” https://www.strategictranslation.org/articles/predicting-the-future-chinas-composite-national-strength-in-2049

“The current CCP Constitution, revised at the Twentieth Congress in 2022, goes further in promoting Xi Jinping’s thought as the great adaption of Marxism to China’s needs today. It has also enshrined the ‘Second Centenary Goal’ – that is, building a great modern socialist country in all respects by 2049 – and ‘common prosperity’ (gongtong fuyu 共同富裕).” https://press.anu.edu.au/publications/chinese-communist-party

China shall fulfil its destiny by 2049, a destiny decreed by China’s Marxist historicism that declares it inevitable that China regains its global primacy, its natural leadership of the world. So Tibet must be fully assimilated by then, not only by coercion but also be persuading all seven million Tibetans [2020 census] to embrace the single, unitary Zhonghua race as their identity and loyalty, not begrudgingly but of their own volition.

Given the depth of Tibetan attachment to land, clan, kin and family; and to Tibetan language as its medium, it is hard to imagine this “self-revolution” can be achieved by 2035. The tearing apart of Tibetan families by closing village primary schools, insisting on taking children to urban boarding schools, began to intensify around 2010. So it is only one generation, from 2010 to 2035, to break family bonds. But 2049 is four decades of destroying families, and cultural continuity.

ANTICIPATION, EXTRAPOLATION, SPECULATION

This post hopes to stimulate debate about the future of Tibet, a debate initiated by Tibetan exile community initiatives, in New York, Paris and Dharamsala in 2022. Taking a longer term view broadens the horizon, but nothing is inevitable, even if China’s ongoing plans up to 2049 are sobering.

What also becomes more coherent when 2035 and 2049 are our frames, is that all of China’s policies push Tibet in one direction, they all cohere. We see the emergence of the economy -wealth creation- as the purpose of life. From cost centre to profit centre; from self-reliance to integration into China’s national power grid, national rail grid, national highway grid; accelerating speed and shortening distance.

All of China’s policies take as their foundational premise that the Tibetans are a backward, primitive, ignorant, unproductive and ungrateful lot. These assumptions are seldom said, not only because of propaganda slogans but because there is no need, no contestation, no debate. To almost all Han, it is self-evident that the Tibetans are lazy and backward, so it is legitimate to shunt them around.

Whether we focus on language policy in Tibet, human rights violations, dam construction, nomad displacements, frontier villages, national parks, mining, we see a common pattern. We see the steady shunting, ongoing disempowerment, depopulation, sedentarisation, relocation, control, dependency of Tibetans under close surveillance. We see cultural continuity torn apart.

We see what all the Xi Jinping slogans add up to, on the ground. We see the direction China is pushing Tibet, which may or may not succeed. We owe it to the seven million Tibetans in Tibet to share with them the evolving scenarios of Future Tibet. Otherwise they have access only to China’s intentionally misleading propaganda slogans.

From a Buddhist perspective, trying to anticipate the future is as pointless as obsessing about exactly what you did in the past to warrant your current situation. Everything is in flux, too many causes and conditions.

Yet China does take very seriously its top level design, its big data-fuelled algorithms that detect patterns and trends, and extrapolate these far into their future scenarios. Because the party-state is fixated on a knowable, predictable, doable, securitised future it is worthwhile tracking China’s planned path.

Our conclusions may be sobering, as were the scenarios generated by the future of Tibet scenarios generated by exiled young Tibetans. Yet they also reveal China’s assumptions, plans, projections in a coherent joining of the dots. China’s ambitions go beyond making all Tibetans visible to state scrutiny, governing Tibetan bodies. China has persuaded itself it can, must and will change Tibetan minds, engineer souls, 人类灵魂的工程师, to use a high Stalinist phrase the CCP embraces.

China’s new textbook of assimilation “reflects the urgent need for ethnic regions to cultivate souls and educate people with history. General Secretary Xi Jinping stressed that we should make full use of the research results of the Chinese Civilization Origin Exploration Project and other research results to tell the ancient Chinese history more completely and accurately, and better play the role of educating people with history. Through historical narrative, the “Introduction to China’s national Community” fully reflects the objective requirements of cultivating the soul and educating people with history in ethnic regions.”

James Leibold, who has closely tracked China’s ethnic policies for 30 years says “Party leaders (and teachers in particular) must actively mould the thought, argot, behaviour, and bodies of all PRC citizens, with minority nationalities requiring special attention due to their perceived backwardness.”

CITY LIFE

Ethnographer Dorje Tashi (Duojie Zhaxi), a graduate of universities in Qinghai, Philippines and Colorado tells us “The recent rapid increase in the number of Tibetan youths moving to Xining has also been motivated by their explicit aspiration for personal autonomy, freedom, and adopting other signifiers of urban lifestyle and a “modern” way of being. In Amdo, after the implementation of rural revitalization strategy which provided villages with modern facilities and public services such as streetlights and concrete roads, community elders began to consider their villages to be mini cities.

“Young Tibetans, however, do not share their views. For the younger cohort, the urban is characterized not by public infrastructure but rather by non-agricultural labour, spaces that give them freedom, availability of amenities such as shops, bars, malls, and movie theatres, and non-agricultural employment opportunities. Tibetan youth describe their villages as boring and a place of narrow-minded people. In contrast, cities are understood as progressive, developed centres, and thus modern. Young Tibetans’ perception of rural/urban and village/city dichotomies reflect state discourse of quality or suzhi. People who reside in cities, Han Chinese areas, and economically advanced places are understood to have higher suzhi than those living in the villages, minority areas, and other ‘underdeveloped’ backward regions. During our casual chat, when I asked what they like most in Xining, rang dbang (freedom) is what both mentioned first. To gain specific insights on what they meant by freedom, I asked them to provide some examples. “You know, yak yak (makeup) is what most us [girls] like to do, and we can do it here. We are now in the city, not in the village,” said Sangdol. Wearing fashionable clothes are also what young men mostly desired upon their arrival in Xining. For instance, a twenty-two year- old man from Guinan County explained that “ripped jeans are the most stylish jeans everywhere, right? But for villagers, such jeans, including the tight pants for boys are seen as clothes for skya stong (bad boys), I don’t wear them in the village although I’d like to, but nobody cares here [Xining].

“Freedom (Tib. rang dbang) is what all my interlocutors desire and appreciate most during employment in Xining. The prospect of working in Xining expresses a high degree of independence and autonomy that is not possible in village setting. many young Tibetans working in Xining equate “modern” and urban status with personal autonomy and freedom from traditional customs.

“For Tibetan youths in Xining, the discourse of modernity is embodied in their everyday life. Young Tibetans in Xining frequently employ a language of liuxin and shishang, which in Chinese literarily means “fashion,” and deng rabs and deng sang in Tibetan, referring to the modern age, or the contemporary period, to explain the dichotomy of city and village. A young man in his twenties, for instance, noted that:

“People in the village still live in the past. They often like to compare what they see and experience, at present, with similar things they faced and experienced in the old days. They rarely take rapid social transformation (spyi tshogs kyi ‘gyur ldog) and progress (yar rgyas) beyond the village into account in their everyday life. Sangje, a young man from Trika, who worked as a waiter at Jamtsan’s restaurant, had obtained a hotel job in Shenzhen and opted to move there, because it is an even bigger centre for urban amenities.

“At the same time, Sangje’s friend, who worked with him at the same restaurant also decided to go to Shenzhen with Sangje, although Sangje’s friend did not find a job there. “For them, the bigger the city is, the more entertaining it is. Moving to a larger city is what most young people desire,” Jamtsan said. Most Tibetan youth also understand that their migration to Xining as an opportunity to “open their ears and eyes” (Tib. rta rgya thos rgya pheye ba).”[3]

If those outside Tibet have not much to say to those inside, what guidance is available? Right now there are more smart phones in Tibet than people, and even in remote areas instant access to all the seductive influencer shills of city glamour. Right now the only thing preventing mass migration of Tibetans to the cities is the party-state’s intense fear of Tibetans gathering in crowds. Roadblocks, security checks, police prohibitions prevent Tibetans from living in cities; but the yearning exists.

Scenario: by 2035, will China relax its fears of Tibetans gathering in cities to demand their lawful rights? Will the clampdown on Tibetan mobility persist in 2035? Or will it take until 2049, a new generation of assimilated Tibetans schooled to believe they are all Zhonghua, one race with the Han, until the Tibetans become just one ethnic group in the melting pots of city life?

Exiled Tibetans in NY Jackson Heights, London Woolwich, Toronto Parkdale, Sydney Campbelltown know all about that, in daily life.

If we cannot discern the flaws in China’s utopian slogans for 2035 and 2049, what can we say to the seven million Tibetans in Tibet? If we cannot name the racism of China’s foundational assumptions about Tibet, we cannot unravel the grand scale future plans grounded in false assumptions. We need the bigger picture.

Footnote to Future of Tibet:

On the first day of 2025 the leading CCP theory journal Qiushi [Seeking truth] published a long speech by Xi Jinping to top leaders almost two years earlier. Here are some of his key points which reinforce the perspective of this blogpost, that the Future of Tibet is in the hands of a party elite who are utterly obsessed with risk, demand all protest be quelled instantly, and proclaim themselves masters of the universe, uniquely capable of implementing the “laws” of modernisation, thus inventing a new form of human civilisation.

Original in Chinese: http://www.qstheory.cn/20241231/d21bd57c012d4d29824219effd18ca35/c.html

English translation by Bill Bishop, on Sinocism substack:

https://sinocism.com/p/xi-in-qiushi-comprehensively-advancing

“Chinese Modernization Has Created a New Form of Human Civilization

四、中国式现代化创造了人类文明新形态

“Chinese modernization is deeply rooted in China’s fine traditional culture, reflects the advanced essence of scientific socialism, draws on and assimilates all outstanding achievements of human civilization, represents the progressive direction of human civilization, and displays a new vision of modernization different from the Western model. It is, in fact, a completely new form of human civilization.

“It thus offers a Chinese solution for humanity’s quest for a better social system.

“The highest-level top-level design for advancing Chinese modernization. Realizing development goals at each stage and in each sector also calls for top-level design. When conducting top-level design, it is essential to gain a deep insight into global development trends, accurately grasp the shared aspirations of the people, and thoroughly explore the laws governing economic and social development

“Advancing Chinese modernization is an exploratory undertaking, one that involves many unknowns. We must boldly explore these in practice, driving progress through reform and innovation. Particularly in cutting-edge practices and unfamiliar arenas, we should encourage bold exploration and pioneering efforts, seeking ways and methods to effectively address new contradictions and challenges.

“Daring to struggle is embedded in our Party’s very genes and is a distinctive trait forged over a century of practice. Advancing Chinese modernization is an entirely new undertaking with no precedent in history, and it will inevitably encounter both foreseeable and unforeseeable risks and challenges, difficulties and obstacles, and even tumultuous storms.

“We must heighten our awareness of potential dangers, persist in thinking in terms of worst-case scenarios, remain vigilant even in peaceful times, prepare for contingencies before they arise, and have the courage and skill to carry on this struggle. Only through tenacious struggle can we open up new horizons for our cause. History has repeatedly proven that striving for security through struggle brings genuine security, while seeking security through weakness and concession ultimately leads to insecurity; seeking development through struggle brings real development.

“We must keep a firm grasp on all kinds of risks and challenges. Currently, China’s development has entered a period in which strategic opportunities coexist with risks and challenges, while factors of uncertainty and unpredictability have markedly increased. China’s economy faces triple pressures of shrinking demand, supply shocks, and weakening expectations. There are numerous hidden risks that could undermine social stability, and “black swan” and “gray rhino” events may occur at any time.

“We keep our nation’s destiny for development and progress firmly in our own hands. We must accelerate the establishment of a new development pattern that allows for internal circulation, while leveraging our super-sized domestic market to attract global resources and production factors.

“We must maintain strategic initiative and strengthen our ability to struggle. Senior officials must possess keen insight and foresight regarding risks. In other words, they need the capacity to detect, from the rustle of grass and leaves, that a deer has passed by, or from the stir of the pines, that a tiger is approaching; to perceive the autumn chill from the change in a single leaf. Nowadays, various potential risks and hidden dangers are highly interrelated, prone to chain reactions, and transmit rapidly. A moment’s carelessness can trigger a “butterfly effect”: small risks might escalate into major ones, local risks into overarching threats, and economic or social risks could even become political ones. Therefore, in our minds, we must have a comprehensive panorama of risks across all areas and fields, continually analyzing and assessing them. We must scientifically foresee potential hazards, keep a well-stocked “toolbox,” make the first move, and fight from a position of initiative. Once a risk emerges, we need to detect it early, act quickly, command from the front, and make decisive calls when necessary—never letting a small problem snowball into a major crisis or a large issue become an explosive one. We must be adept in the strategies of struggle, refusing to compromise on matters of principle while also placing emphasis on tactical flexibility and countering each move effectively. When needed, we should take the initiative, strike first, and actively shape a favorable posture in our struggles.”

[1] Steve Tsang & Olivia Cheung, The Political Thought of Xi Jinping, Cambridge University Press, 2024, 28

[2] Hu Angang, 2050 China: Becoming a Great Modern Socialist Country, 2022, 58, https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/46096

[3] Dorje Tashi, Tibetan Farmers in Transition: Urbanization, Development, and Labor Migration in Amdo, PhD thesis, U Colorado 2020. https://www.proquest.com/openview/c3f6fe5aa0ab0a3486b1746cfba445dc/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y

One reply on “FUTURE OF TIBET”

[…] By: Gabriel Lafitte | Rukor […]