CHINA, GLOBAL WARMING, AND TIBET

Climate change campaigners understandably yearn for good news, for signs that governments worldwide will get real, in Paris in December, about real action to stop baking the planet. After the utter failure of the last round, in Copenhagen in 2009, to produce substantial commitment to effective earth negotiations, there have been few signs that the biggest greenhouse gas emitters are serious about curtailing their entrenched habit of regarding the air we breathe as a dump. Despite all the dire reports on the likely effects of climate change on just about everything, governments continue to insist they will not do anything substantial until everyone else does too, and at the same time. No one wants to be first.

So maybe it is understandable that the prophets of climate change seize on the slightest signs that states, addicted to polluting the skies, are now changing their ways. Yearning for good news makes the good news happen.

Nowhere is that yearning more intense than over China, the world’s biggest greenhouse gas emitter. China, in the run up to the Paris Conference of Parties (COP) to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCC) has released its formal statement of intent. It is, as one might expect, quite carefully crafted, especially since China was widely recognised as the wrecker of the failed 2009 UNFCC COP in Copenhagen.

This time China seems to have got it right, to be on the side of the angels, on the path to clean air and a cleaner, survivable planet spared the worst of global warming. Here is a quite typical example of how China’s June 2015 climate change policy statement is received: “China’s new pledge to curb carbon emissions is credible and decisive, an encouraging sign that the country is ready and able to accept global responsibilities, at least in some cases. Despite Beijing’s far-from-spotless record in environmental management, last month’s promise looks serious, detailed and substantial.”

So let’s look at the facts. We might not reach the same rosy conclusions.

CHINA’S COAL ADDICTION

First, China’s action plan on climate change allows it to continue to increase the burning of coal, which is already at 3800 million tons a year, as much as the rest of the planet put together. Coal burning, the greatest source of climate heating, as well as seriously toxic chemicals, is to rise, on China’s best case scenario, to 4200 million tons by 2020 and continue rising until 2030.

China remains committed to growing as fast as it can, with a goal that by 2050 Gross Domestic product (GDP) will be 11 times greater than in 2005. This official goal necessitates a staggering consumption of resources from around the world, and from the remotest areas in China. At the same time, as China shifts gradually from being the world’s factory to a service economy, it is also committed to greater efficiency in resource exploitation, to maximise profitability. Greater efficiency means less resource extraction and less greenhouse gas emissions per RMB unit of GDP. But in an economy that is still growing, overall actual resource extraction continues to rise.

This means that greenhouse gas emissions from coal burning electric power stations, currently at 158% of 2005 levels, are officially due to rise to 182 percent by 2020 and 201 per cent by 2030.[1] Thereafter, hopefully, emissions will start to reduce. This is hardly serious, detailed and substantial environmental management. This is China insisting it remains a developing country with no obligations to work as hard as rich nations to cut emissions any time soon.

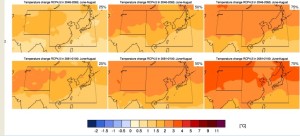

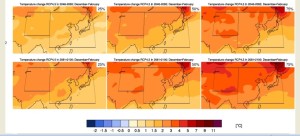

The result will be that the Tibetan Plateau warms fast, faster than anywhere on earth other than the Arctic. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in 2013 published its Atlas of Global and Regional Climate Projections, which map what Tibet can expect in the rest of this century:

IPCC scenarios of summer temperature increases across Tibet. Top row: projections for 2046 to 2065; bottom row: projections for final two decades of 21st century.

IPCC scenarios of winter temperature increases across Tibet. Top row: projections for 2046 to 2065; bottom row: projections for final two decades of 21st century.

IPCC scenarios of winter temperature increases across Tibet. Top row: projections for 2046 to 2065; bottom row: projections for final two decades of 21st century.

HYDRO DAMS TO OFFSET COAL BURNING

China’s ongoing addiction to coal is offset by several other initiatives that, at first glance, greatly improve its climate change commitment. First, as well as stepping up coal use, China is also increasing the use of renewable energy, not only wind and solar but also hydro power. Most of that hydropower increase is to come from the mountain rivers of the Tibetan Plateau as they rush towards lowland China. There are so many dams built, under construction and planned that nearly all the great rivers –the upper Yangtze, Yellow, Mekong and Brahmaputra- rising in Tibet will becomes a cascade series of stepped dams ruinous for migrating fish and aquatic ecosystems; the dams so big and heavy they are prone to trigger (and lubricate) earthquakes. Dam construction, in remote valleys of precipitous Kham, in eastern Tibet, bring huge immigrant workforces that overwhelm local communities, economies, ecologies and sacred mountain pilgrimage circuits. Once all the dams are built, the power generated will be carried across China, by ultra-high voltage power lines, all the way to coastal megacities including Shanghai and Guangdong.

EXCLUDING NOMADIC PASTORALISTS TO GROW MORE GRASS

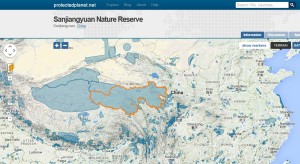

Another way China is now credited for its new seriousness about tackling climate change is the map of nature reserves and national parks which on paper exclude human use, dedicated instead to restoring forest and pristine grassland wilderness, thus capturing more of the carbon emitted by those coal fired power stations. A glance at a www.protectedplanet.net map of China’s officially protected areas shows most are on the Tibetan Plateau, some in arid areas of alpine desert, but much in the best pasture lands of Tibet, including the entire prefectures of Golok, Yushu and more, a rolling green sward 50 per cent bigger than the UK.

China’s protected areas, with the prime pastures of the Sanjiangyuan Nature Reserve of eastern Tibet highlighted. Source: www.protectedplanet.net, a database of the UN Environment Programme.

The best production landscapes of the Tibetan Plateau are now officially zones of human exclusion, all in the name of conservation and climate change mitigation. On a map, this looks like an impressive commitment to grow more grass and sequester more carbon, offsetting all those coal fired emissions. On the ground, for hundreds of thousands of pastoral nomads, it means total loss of livelihood, herded off their land into concrete barracks often far from their lands, their herds compulsorily sold, with no training to enter the modern cash economy of wage labour. China’s justification is rangeland degradation, a problem best dealt with by including the pastoralists as part of the solution, implementing the reseeding of bare areas, the best people to care for the rehabilitation of areas where, due to official policy, animals were concentrated more than the land could bear. There are now many Chinese scientists who identify the cause of overgrazing and degradation as a succession of “improper” official policies that forced nomads onto small allocated plots.

SHIFTING POLLUTION AND EMISSIONS WESTWARD

Why is China in no hurry to curtail its coal consumption, clean its skies, mitigate climate change and pull its considerable weight in global efforts to prevent disastrous planetary warming?

China is huge, and the pressure for change comes from the east coast cities, where articulate citizens, including plenty of party members, demand clean air. The simplest solution is to shift the dirtiest factories inland, far inland, as far as the foot of the Tibetan Plateau, to megacities including Chengdu and Chongqing. Elizabeth Economy, of the Council on Foreign Relations, notes that: “as China shuts down power plants and coal mining in the eastern provinces, they are planning to move the plants and mines to the country’s western regions. Thus, while some of China’s major coal-related initiatives will do much to improve domestic air pollution in the coastal provinces, they won’t produce the same benefits for climate change.”

This is where Tibetans get hit with a double whammy. On one hand, in the name of conservation, Tibetans are excluded from ancestral pastures. On the other hand the miners move in to lands no longer protected by living Tibetan communities, and the minerals extracted feed the new factories of the Fortune 500 relocated to Chongqing and Chengdu. On paper, China looks good: committed to protecting huge dryland areas from degradation; while in practice, off the books and out of sight of international scrutiny the miners move in.

THE WATER DIVIDEND

It is not only minerals that Tibet provides to the world’s factory as it moves to Sichuan, Gansu and Qinghai provinces. Tibet’s number one purpose is to provide water and hydro-electricity to downstream lowland China. Climate change is already producing a dividend for China, in the form of increased river flows and rising lake levels across the Tibetan Plateau, as glaciers melt and rain increases.[2] According to the scientists who study paleoclimate, the Tibetan Plateau has been slowly desiccating for thousands of years, with lake shorelines gradually dropping for millennia. But in the past few years this trend has reversed. This dividend will continue to pay out for several decades of climate warming to come, until eventually the glaciers are all gone. Why jeopardise such a dividend?

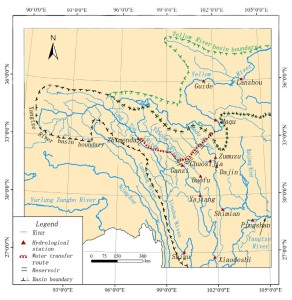

China’s scientists are now intensively monitoring the effects of climate change on Tibetan rivers due to be dammed and diverted, to feed extra water into the upper Yellow River in the hope of alleviating the drying out of the river that gave China’s civilisation its start. Recent research sponsored by the China Meteorological Data Sharing Service System, and the Bureau of Hydrology and Water Resources of Sichuan Province, has found that this massive project, officially the south-to-north water diversion western route, will be of greater benefit in coming decades as accelerating climate change will mean less seasonal synchrony between the heavily monsoonal upper Yangtze and the much drier upper Yellow River.[3] By factoring in the likely effects of climate change, scientists from the State Key Laboratory of Hydraulics and Mountain River Engineering, and the College of Water Resource & Hydropower, both part of Sichuan University, make the strongest possible case for going ahead with a project they call “the most magnificent trans-basin water diversion project in the world.”

The canal to be constructed runs across the most troubled areas of the Tibetan Plateau, across Kandze and Ngawa (Aba in Chinese) prefectures, where most of the public protest suicides by Tibetans have occurred in recent years

Planned route of dams and canal to divert Dri Chu (Yangtze) to Ma Chu (Yellow River).

Source: HUANG Xiao-rong, ZHAO Jing-wei and YANG Peng-peng; Wet-Dry Runoff Correlation in Western Route of South-to-North Water Diversion Project, China; Journal of Mountain Science, (2015) 12(3): 592-603

A CROPPING DIVIDEND

One further reason China sees itself as due for a payoff from accelerating climate change is the prospect of growing more temperate climate crops on the eastern Tibetan Plateau in coming years, as the climate heats. A major reason China has found it difficult to populate the Tibetan Plateau with politically reliable immigrants is that the frigidity of Tibet prevents the farming of grassland, especially the labour-intensive small plot traditional Chinese peasant farming that can employ lots of people. But if the climate warms, in coming decades it may be possible to grow more forest in eastern Tibet, and also open up new cropland.[4]

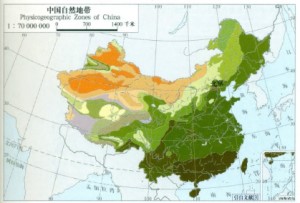

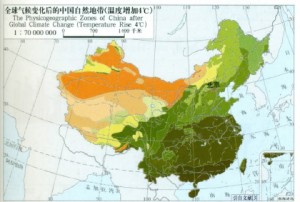

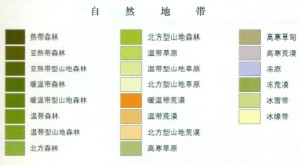

The official Geographic Atlas of China published in 2010 maps the likely effects of a 4°C temperature rise –double the redline danger zone of 2 degrees- on the productivity of the Tibetan Plateau, under two scenarios: no rainfall change, and a 10% rainfall increase. Both maps show a strong westward shift of forest into Tibet, the greatest being for the likeliest scenario, of increased rain accompanying increased temperature.

Plant growth zones of China 2010. Source: Geographic Atlas of China, Sinomaps, 2010 p 72

Plant growth zones of China after global warming adds 4 degrees C.

Plant growth zones if warming reaches extra 4 degrees C, plus 10% more rain

热带森林 Tropical Forest

亚热带森林 Subtropical Forest

亚热带型山地森林mountainous forest with Subtropical type

暖温带森林 Temperate zone forest

暖温带型山地森林 Mountainous forest shaped with temperate zone

温带森林 Temperate zone forest

温带型山地森林 Mountainous Forest shaped with temperate zone

北方森林 Northern Forest

北方型山地森林 Mountainous forest with type of northern forest

温带草原 Temperate zone grassland

温带型山地草原 Mountainous grassland with type of Temperate zone

北方型山地草原 Mountainous grassland with type of north

暖温带荒漠 Temperate zone Desert

温带荒漠 Temperate Zone Desert

北方型山地荒漠 Mountainous desert with type of north

高寒草原 Altitude Cold Grassland

高寒草甸 Altitude Cold Grassy Marshland

高寒荒漠 Altitude Cold Desert

冻原 Tundra

冻荒漠 Cold desert

冰雪带 Ice-snow belt

冰原带 Ice Sheet zone

The entire plant growth zones of China will move more than 300 kms westward in coming decades. For example, mountain forest with subtropical species on the lower slopes will, on these maps, spread to the Nyenchen Tanglha range of central Tibet, and the shores of Lake Namtso.

That is what China expects. The science of such forecasts is far from exact, the reality on the ground 35 or more years from now may be quite different. But China’s policies are based on such expectations.

Such expectations are not based on ground truths of actual climate change already happening fast in Tibet, which is shrinking permafrost, lowering water tables, drying out wetlands and robbing young crops of soil moisture that melts away in spring long before the summer rains arrive. The rosy expectation of a climate dividend for China in Tibet is based on extrapolating remote sensing data gathered by satellite, not on ground observation.

Taken together, these are the many reasons China knows it must talk the talk on climate change, but is reluctant to fulfil the hopes of the world as it looks to the UNFCC Paris COP in December 2015. China has so far successfully resisted all calls that it specify emissions reductions. China has bought time, and credibility with conservationists, by declaring half of the Tibetan Plateau to be nature reserves, and by talking about growing more grass on those depopulated pastures as China’s great contribution to capturing carbon.

Little wonder then that Tibetans coming to the Paris climate change negotiations ask the world’s conservationists to see beyond the plausible but vacuous slogans of China’s announcements.

[1] An Analysis of China’s INDC , Fu Sha, Zou Ji, Liu Linwei, China National Center for Climate Change Strategy and International Cooperation, http://www.chinacarbon.info/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Comments-on-Chinas-INDC.pdf

[2] Climate change, glacier melting and streamflow in the Niyang River Basin, Southeast Tibet, China.

Zhang MingFang; Ren QingShan et al; Ecohydrology, 2011, 4, 2, 288-298

[3] HUANG Xiao-rong, ZHAO Jing-wei and YANG Peng-peng; Wet-Dry Runoff Correlation in Western Route of South-to-North Water Diversion Project, China; Journal of Mountain Science, (2015) 12(3): 592-603

[4] XU Huajun, YANG Xiao鄄guang, et al; Changes of China agricultural climate resources under the background of climate change. VII. Change characteristics of agricultural climate resources in arid and semi arid region of Tibet Plateau. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecoogy,2011,22(7): 1817-1824.