Blog two of three on realities of China’s labour market for displaced Tibetans

China is urbanising fast, including in Tibet. From a distance, out on the open range, urban life can look tempting. Up close it’s a relentless hyper-competitive race.

China’s big consumer brands are in constant need of heroes, nudgers, validators, influencers or, as they are called in China KOLs -Key Opinion Leaders. The biggest brands snap KOLs up, exploit them and spit them out. What could be better marketing than a bright young Oxford prof who is a byword for authenticity, being true to yourself, keeping it real?

Little likelihood Xiang Biao would do that. izsHis emergence as a culture hero is based on decades of careful fieldwork, listening attentively to the migrant workers, gradually discovering that the kind of mobility now meant to include even remote Tibetans, has become the defining characteristic of contemporary China.

EXPANDING USES OF GRID MANAGEMENT, TIBETAN STYLE

Xiang Biao illustrates this by comparing the SARS epidemic of 2003 and the Covid pandemic of 2020. In 2003 it was the rural migrants flocking to city work who were the mobile ones, who had no choice but to return to their villages when their work on urban construction sites was shut down, depriving them not only of income but a place to sleep, as they often lived on site. By 2020 the number of migrant workers had grown greatly, but the whole society had bought the idea that mobility is the key to success, and China had become “hypermobile.” This, Xiao reminds us, is a result of China’s transition to an economy based not on farming or factories but services, and the innumerable gig economy jobs done by mobile precariat workers.

In 2003, during the SARS outbreak, although migrant workers had little choice but to return to home villages, taking SARS infections with them, China’s ambivalence about mobility meant migrant workers were stigmatised as spreaders. In 2003 the migrants went home; in 2020 they were locked down, in place. In 2020, China had perfected the grid management it had pioneered in Tibet, then spread to Xinjiang, then established as a model applicable wherever needed, across China. Grid management meant suddenly and totally stopping the hypermobility of the workers, a strategy that did halt viral spread more effectively than the muddled response in most countries.

That made for a short, sharp break in hypermobility, and a quick return to the gig economy and its bullshit jobs, the dead ends after all those years of exam cramming and chicken blood transfusions. Now hypermobility is back, increasingly extending to Tibetans deemed surplus to rural production requirements, and precarity is back.

The precarity of the new urban underclass is baked into China’s state capitalism and the rise and rise of the billionaires whose fortunes rely on taking no responsibility as employers of the underclass. Precarity is more than no job security and lousy pay; it is also the lack of access to health care or education for your kids, if you are one of the 230 million Chinese living in cities but excluded from any right to city services because they remain registered under the hukou system as rural. The cruelty of the hukou household registration system has been den oinked for decades as a basic contradiction, in a country where urbanisation is promoted as the prime path to poverty alleviation, yet 230 million urban folks are systemically second class.

Since their work is insecure, with no employer provision of welfare or even sick leave, and they are not entitled to urban health care or schools, not surprisingly those stuck in bullshit jobs save as much as they can, their only safeguard if things go wrong.

It is those savings that are at the heart of the party-state’s most recent campaigns to foster a shift towards an economy driven by consumption rather than by official investments. If only the underclass could be persuaded to spend more, the macro-economists urge, has the potential to unleash a wave of spending that lifts all boats, but especially the fortunes of the fintech billionaires, who would benefit most. In today’s China, that’s a compelling argument for finally loosening or even abolishing hukou. “Granting rural-born migrant workers the right to settle permanently in cities could raise their consumption by 27%, even assuming no change in their wages or other conditions.”

THE RETURN OF CLASS TO A NEWLY PROSPEROUS BUT DEEPLY UNEQUAL CHINA

China officially reveres Marx, champion of the downtrodden urban proletarian underclass struggle for social justice. In practice the ruling CCP elite is indistinguishable from the hyper-wealthy elite, and inequality keeps widening. Only a handful of academic sociologists dare talk about class, Xiang Biao among them.

Throughout the modern world we see the new underclass everywhere: the fast-food delivery riders, uber drivers.

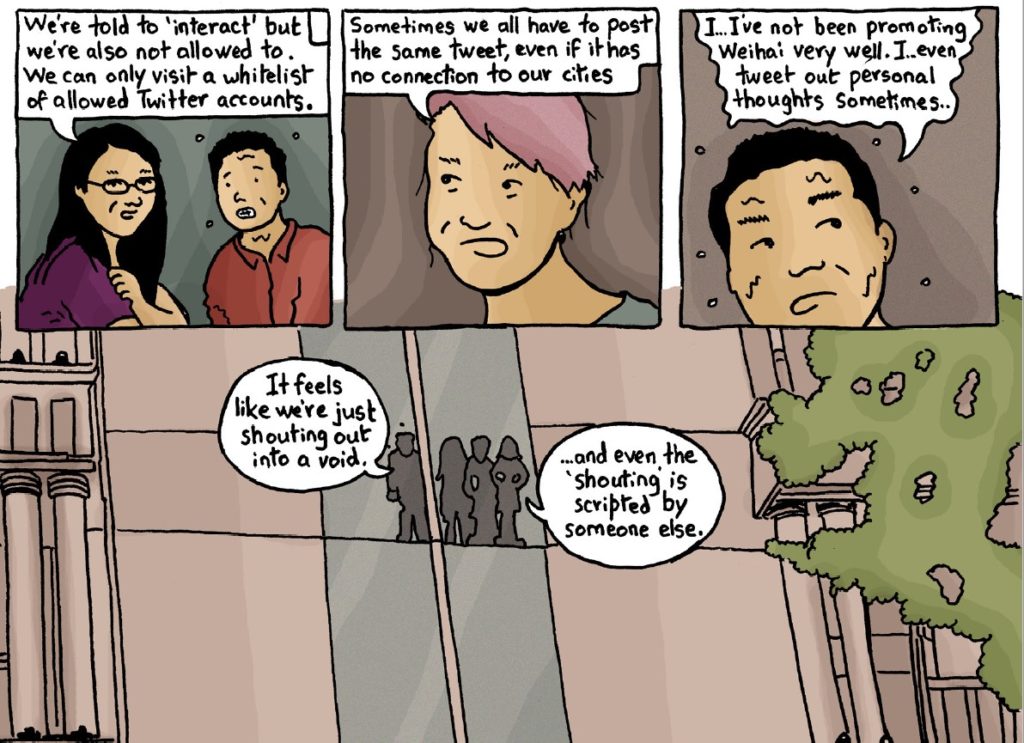

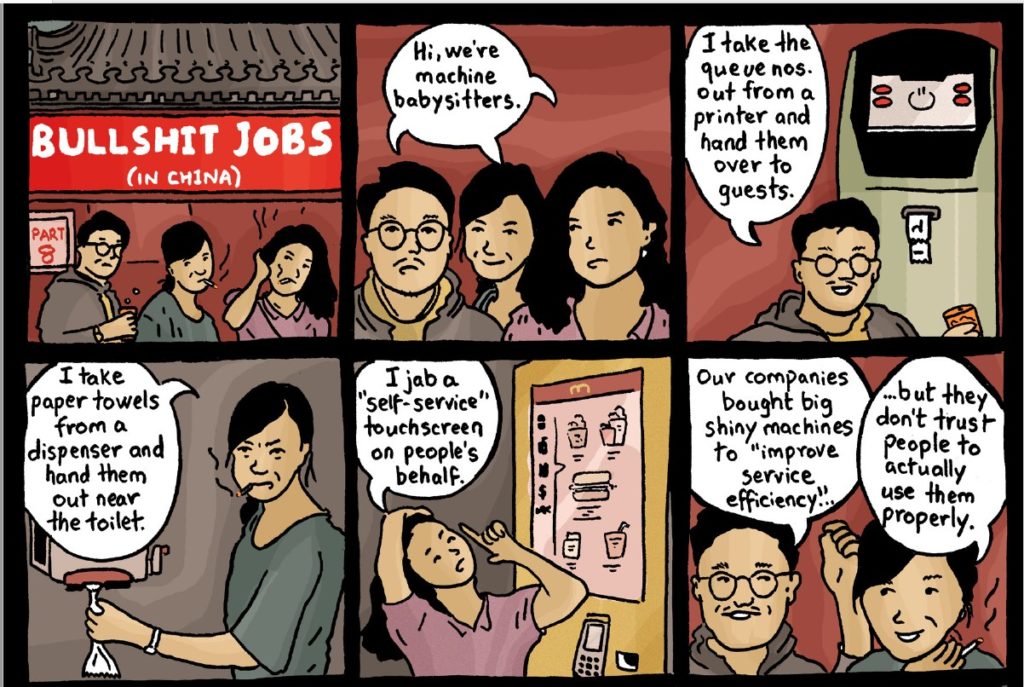

But China has taken this further, inventing many more bullshit jobs than you might have imagined, such as Guinness Book of Records verifier, the guy you pay to stand in line for a seat in a fashionable restaurant so you can then glide in and eat, the arbitrageur of the coolest sneakers, the guy who collects dumped e-bikes and brings them back to where people want one to hop on to, the list goes on. There’s the woman who airbrushes online images to conform to censorship decrees, the tweeters paid to promote local destinations, the machine minders paid to maintain illusions of seamless automated efficiency.

Other cataloguers of bullshit jobs write about this, among them grunge punk music sceners chronicling the energies of underclass losers, a parallax China of wild creativity and avant-garde pioneers, whose music has by now been around for 25 years. “The idleness of China’s so-called “wasted youth,” kids who’d dropped out or were asked to drop out of the narrow path to money and success, led to a very particular kind of ferment — in art, in music, in writing. Beijing’s punk scene, especially the cluster of bands that formed around Scream Club in Haidian, were of this ilk, and Wuliao JunDui (The Bored Contingent) laid the foundations for an entire country’s punk underground out of sheer boredom.”

Some of the best chroniclers of the lie flat underclass are musicians and comics illustrators, such as Krish Raghav, whose graphics illustrate this blog (with permission). The creativity and musicality of the lying flats suggests there is more to them beyond refusal to conform to the norms of accumulation.

Withdrawing from the rat-race, opening to the authentic in nature, in quiet receptiveness, has much deeper roots in Chinese tradition, especially Taoism. Since China is at last rediscovering its cultural heritage, after a century of repudiation, this could be a promising basis for lying flat to grow into a counterculture. There is much more to Chinese tradition than the official party-state versions of Confucius and the Legalists.