GEOLOGISING THE ROOF OF THE WORLD

In 2013 the 25,000 worldwide members of the Geological Society of America will celebrate the organisation’s 125th birthday. GSA is a global fraternity of the profession of geology, and is flourishing. Fed by competitive resource nationalisms, fears expressed by governments that they should not have to depend on other countries for “strategic” resources, geology is in demand.

New frontiers and new career opportunities are opening up. Promising new frontiers include the Arctic, now that climate change has melted so much sea ice that the ocean floor is accessible to drilling, and the Tibetan Plateau, long suspected to host major mineral deposits.

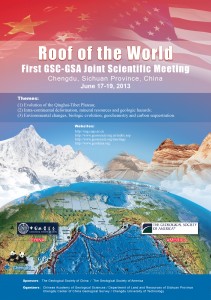

GSA is celebrating its 125th birthday with a “Roof of the World” conference at the foot of the Tibetan Plateau, in Chengdu, a major city of western China rapidly shaping up (with nearby Chongqing) as the capital of western China, and a global factory reliant on exploiting Tibetan resources.

Although billed as a “scientific meeting” jointly sponsored by China’s professional geological organisation, the agenda on the poster advertising the June 2013 meet specifically names “mineral resources” among the more evidently scientific questions of the tectonic origins of the Tibetan Plateau etc.

As China has made Tibet available to global scientific scrutiny, many sciences have come to Tibet to map, explore, experiment and report their findings. No science working in Tibet has been as engaged with China as global geology.

It is understandable that geologists worldwide have been fascinated to research the origins of a plateau uplifted kilometres into the sky, in a process that geologically is quite young and ongoing. But geology, as a profession, makes no clear distinction between geology as a science contributing fundamental knowledge of earth dynamics, from economic geology of mineral deposits and their suitability for exploitation. That blurring of key ethical divides has consequences for Tibetans, who have no power to speak for or defend their communities, lands, sacred lakes and mountains from mining, no right to form community based organisations to articulate their concerns.

Tibet is not just another frontier for scientific curiosity which might just happen to lead to mining. It is not an accident that so many of the Tibetans who recently chose the one method of protest left, burning themselves to death, were from areas disturbed by the intrusion of Chinese mining operations into remote Tibetan mountain communities.

It is perhaps no accident that the GSA 2013 poster advertising its “Roof of the World” conference shows a map linking the US and China across the Pacific, but does not extend to depict the actual global roof, stopping instead at the conference venue, Chengdu.

The city of Chengdu is not a normal city, as Colorado-based anthropologist Emily Yeh recently discovered: “I gave the taxi driver at Chengdu’s Shuangliu airport the name of the hotel in Wuhouci, the small Tibetan neighborhood in Chengdu, where I often stay. “Don’t go there,” he immediately advised, “The security is bad. I’m telling you the truth. That entire street is full of Tibetans. Everyone there is a Tibetan. There are security vehicles everywhere. It’s no good.” He tried to persuade me to go elsewhere and fell silent when I refused. As we arrived, he pointed out the police car with flashing lights by the side of the road, then another, and another. “See?” he said, “I told you.” “But why is the security bad? Did something happen?” I asked. “This whole street is full of Tibetans,” he said, as if he had offered an adequate explanation. “Who knows? You know, they have guns and stuff.”

The collaboration between American and Chinese geologists in Tibet goes back decades, and has led to many useful insights into plate tectonics and a host of scientific findings. There is no clear divide between such basic knowledge, and economically profitable knowledge that makes fortunes by exploiting Tibet. A study of the extreme pressures generated by colliding continents can explain how rocks melt and then cool slowly enough for molten minerals to separate into rich deposits.

This is not the first round of geological engagement with China, but it might be the first that leads to serious wealth accumulation. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the giant transnational energy corporations came to China, on the basis of highly promising preliminary findings by Chinese state geological exploration teams, to set up what promised to be major new oil fields. Instead, nothing much was found, and Chinese geology cadres, whose promotion depends on generating upbeat reports, were blamed. In 1993 China slipped below self-sufficiency in oil, and has since become a huge importer.

Now world geology is back, keener than ever to work with Chinese geologists, even at a time when China’s government has defined mapping of China by foreigners as a threat to state security. The “Decision on amendments to the ‘Interim Measures for Administration over Foreign Organizations or Individuals Surveying and Mapping in China’”, issued by China’s State Council in June 2011 shows a distinct ambivalence about the legitimacy of ordinary global geological work: “The rapid development of the market for Internet mapping services in recent years has also brought some problems, such as uploading and marking of geographic information and publication of problematic maps that endanger state sovereignty and undermine the dignity of the nation. All of this constitutes serious, hidden risks to China’s national security.”

In the 19th century the institution at the forefront of imperial expansion was the Royal Geographical Society of Great Britain. Like GSA today, it was nominally just a professional association, but in reality it spearheaded Britain’s colonial expansion. Geological Society of America has a similarly global reach, and needs a global ethics that matches its reach. Such standards are not hard to find, such as the Equator Principles or the International Council on Mining and Metals guidelines on working with indigenous communities. The bottom line is the informed, explicit consent of the locals, after the interventions of the geologists, and the possible consequences, have been explained to the locals in a local language. Geologists operating in Tibet, whether academic or economic, whether Chinese or international, have never gone through such a process of consultation and consent.

The Colorado-based GSA has position papers on various issues, including the importance of government funding of scientific geology to discover mineral resources. GSA’s 2011 official position is that: “GSA recommends increased public investments and public‐private partnerships to improve our understanding of mineral and energy resources and to support programs for renewable energy resources, energy efficiency, and resource recycling. Sustained public investments are essential to ….. exploration for new resources to replace depleted ones. Federal, tribal, state, and provincial governments should support mineral and energy resource assessments and related land management needs, physical sample preservation, and development of new knowledge about possible future resources. Enhanced partnerships between government and industry can improve access to land and foster new technology developments. Private foundations and public funding agencies can also support research related to mineral and energy resources.” http://www.geosociety.org/positions/pos11_GovInEnergy.pdf

GSA’s pro-development agenda emphasises making tribal and communal land available for mining, rather than putting first the needs of remote communities which may prefer to be free of mining.

GSA’s partner in Chengdu in 2013 is the Geological Society of China http://www.geochina.org/ which shows how deeply integrated it is with global economic geology by advertising on its splash page for attendance at a July 2012 New Hampshire conference on geochemistry of mineral deposits, with an emphasis on the kind of combined gold and copper deposits exciting most Chinese and Canadian investor interest in Tibet. For both GSA and its Chinese partner, GSC, it is but a short step from science of the lithosphere to exploring rich deposits of gold.

The other Chinese organisation listed on GSA’s announcement of the 2013 conference is the Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences, which has a division dedicated to mineral resources and publishes a regular Chinese language journal called Mineral Deposits http://imr.cags.ac.cn/ .

As yet there are few large mines in Tibet, outside of the Tsaidam Basin of arid northern Tibet, where China has exploited oil, gas, salts, lead and zinc for decades. Only now are mines, on a global scale, being built in central Tibet.

2013 is a crucial year: it is not too late to step back from abetting China’s exploitation of Tibet, without the consent of the Tibetans. 2013 is the centenary of British imperialism stepping back from over reach, handing back, at a meeting in Shimla, India, “suzerainty” over Tibet to China. The Tibetans were not asked to agree.

Geology, as a global profession, is deeply enmeshed in the upcoming intensive exploitation of the Tibetan Plateau. It is no longer sufficient to say, as GSA says, that there will be plenty of good basic science to discuss in Chengdu in 2013, at a conference in which almost no Tibetans will be present during the “Roof of the World” sessions. In the conference poster listing of topics basic geological research is inextricably connected with exploitation. So too on the ground, and beneath it.

Although purely academic geologists may consider economic geology beneath them, there is no clear separation, which is all the more reason for GSA to have clear protocols enabling its members to know when they have crossed the line and are abetting exploitation without the consent of the local Tibetan communities.