MATERIAL WORLD

A blog series on China’s lust for lithium from Tibet, blog 1 of 3

A concise version of this blog was published by Turquoise Roof. If you have read that report, do read on for further insights into China’s long term strategy for global dominance of all new industries, and in-depth analysis of the actual environmental costs of rock lithium extraction, and lithium battery manufacturing in China. Does the planetary pathway to decarbonisation really require a massive expansion of mining?

Also, in this long read, more on Elon Musk and Warren Buffett, the backstory on Sichuan province’s great leap forward, why battery powered cars are designed to appeal to male egos, and the likelihood of rare earths in the Tibetan rock lithium deposits. And we discover the heroic lone Chinese engineer, in the Audi factory paint shop, back in year 2000, who engineered the entire trajectory of China’s global dominance through lithium, So do read on…..

FACTORY CITIES SURROUND THE TIBET COUNTRYSIDE

Was there ever a material girl living in a material world quite as material as this? “We must deeply realize that the modern industrial system is the material and technological foundation of a modern country. Accelerating the construction of a modern industrial system supported by the real economy is related to our strategic initiative in future development and international competition. Industrialization is the premise and foundation of modernization. China has become the only country in the world with all the industrial categories in the United Nations industrial classification. Its manufacturing scale has ranked first in the world for 13 consecutive years, and the output of new energy vehicles and photovoltaics has remained first in the world for many years.”

Here comes China, in the passing lane. As it speeds by, we see it is a driverless robo-car, driven by China’s import of 19th century German historical materialism, which defines material mastery as humanity’s ultimate and inevitable utopian flourishing. China, just like its mentor America, now sees itself as tutor of mankind in its pilgrimage to perfection. [1]

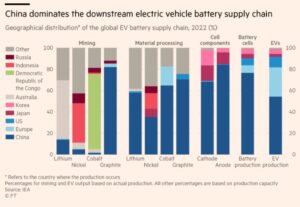

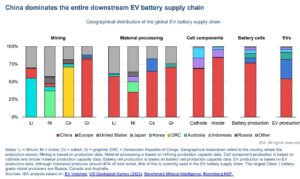

Nowhere is China’s materialism more triumphant than in the tech of a decarbonised world. Solar power, wind power, battery power, hydro power, power grids to connect them all: China has mastered the lot, buys the raw materials worldwide and sells the manufactured result worldwide. Whether it’s a gleaming electric car in a Berlin showroom, a hydro dam in Ghana, [2]ultra-high voltage power grids, [3] mass solar arrays in Tibetan deserts, proliferating wind farms, China dominates it all.

What this adds up to is the Fourth Industrial Revolution, won by China. Numbering industrial revolutions is not a popular pastime, especially when it feeds American anxieties about American decline. Yet THE industrial revolution, in 18th century England, was followed by second and third revolutions in material mass manufacturing, which signalled America’s era.

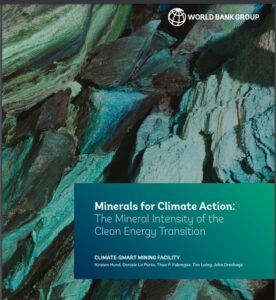

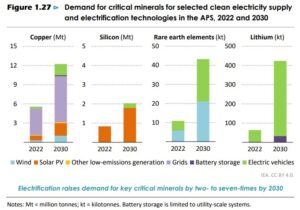

The Fourth Industrial Revolution is made in China, enabled by its mastery of all the technologies of a supposedly clean, green, decarbonised future world, which happens to dig from the earth far more of the critical minerals abundant in Tibet.

CHINA’S NEW ENGINE IS A BATTERY

China’s Innovation-Driven Development Strategy (IDDS), “is Xi’s grand strategy for transforming China into a global innovation power. The IDDS is the conceptual framework for an expansive staple of initiatives and plans that have been promulgated and implemented, such as the Made in China 2025 (中国制造 2025, Zhongguo Zhizao 2025) strategy and the 13th Five-Year Science and Technology Innovation Plan (十三五国家科技创新规划, Shisan Wu Guojia Keji Chuangxin Guihua) from 2016 to 2020.”[1]

Better known globally is the slogan Made in China 2025, which caused such alarm that China was positioning itself in the passing lane, that the slogan was quietly dropped from international usage. China was on a path to comprehensive national strength, but announcing this in advance of attaining it was only exciting nervousness. Better to revert to biding one’s time.

The ambition for securitised national industrial strength in no way disappeared with the discreet retirement of the Made in China 2025 slogan. All the ingredients for a master plan had been fostered by the elite for decades. They needed to be assembled, resourced and then implemented. Internal contradictions, such as the multiple ministries in charge, had to be rectified, building a centralised command and control system. Competing silos and bureaucratic fiefdoms had to be disciplined, if this greatest campaign of a campaigning ruling party was to be realised. Xi Jinping, by a consensus of leaders, was the man to do it.

Xi had plenty to build on. There was already strong awareness that China becoming the world’s factory meant much more than an endless source of cheap labour forbidden to strike or press for a share of the wealth. The world’s factory could not only manufacture anything and everything the world would buy, it could also engineer a new industrial revolution., the epitome of national strength.

For 250 years the world has known that whosoever dominates the industrial revolution dominates the world. From the first industrial revolution, of water, coal and steam in 18th century Britain, to the second, early in the American century, of the assembly line making skilled craftsmen redundant, to the third, the computer revolution of the 1970s, it has seemed natural and inevitable that an industrial revolution is far more useful than a political revolution, which is the last thing the CCP would want.

Could there be a fourth industrial revolution in the making? At the time Xi Jinping took over in 2012, there were plenty of intimations, including the suite of technologies that could displace fossil fuels, and reboot the richer countries as clean, green, decarbonised, post-coal, turning instead to a menu of green tech, including electric cars, solar power, wind power along with nuclear and hydro as further sources of energy. Taken together as a package, these were all technologies China could dominate, whether or not it had the raw materials within its sovereign boundaries.

In popular story telling the hero of this farsighted vision of a fourth industrial revolution is Gang Wan. He alone was the visionary. Way back when, in the Y2K millennium year, he foresaw the future of the entire auto industry was electric, and could be China’s big moment to vault over the dominant players, who would become “legacy”. At the time he worked for Audi in Germany, mostly in the paint department, as an engineer with a PhD from a German technical university, having obtained a scholarship awarded by the World Bank, which invested in China well ahead of private capital discovering “the China miracle”.

CHINA’S MIRACULOUS CONVERSION TO LITHIUM AS NATIONAL SALVATION

The hero story, as told in at least two books, is that he not only had his patriotic vision, he had a miraculous opportunity to put it before China’s rulers.[2] China’s Minister of Science and Technology, Zhu Lilan, was visiting Germany, including Audi. At 65, Zhu was nearing the end of her ministerial role. She invited Wan Gang to present his vision to China’s State Council, or cabinet.

Not only did the State Council buy his vision, by 2007 Wan Gang was the Minister of Science and Technology, in charge of making it happen. A classic Hollywood hero journey, complete with the early crisis of being banished as a young man to the forests on the northern wilderness during the Cultural Revolution.

A more insightful telling of China’s embrace of lithium battery cars and all green energy tech comes from Tai Ming Cheung, in his 2022 book, Innovate To Dominate: The Rise of the Chinese Techno- Security State. Cheung lists the key figures who designed China’s rise to tech mastery, including Wang Gan.

Cheung: “The finalized version of the IDDS [Innovation-Driven Development Strategy] was approved by the Chinese authorities in the spring of 2016 and an outline (纲要) was issued by the Party Central Committee and State Council in May 2016.20 The outline was described by Wan Gang as a top-level design and systemic plan that established the goals, directions, and priorities for China’s innovation-driven development over the next three decades. Wan said the IDDS built on the 2006–2020 Medium-and Long-Term Science and Technology Development Plan (中长期科学和技术发展规划纲要, Zhongchangqi Kexuehe Jishu Fazhan Guihua Gangyao) and the midterm evaluation of major S&T projects carried out under this plan.

“Barry Naughton, a leading expert of the Chinese economy at the University of California, San Diego, argues that the IDDS should be considered primarily as a highly sophisticated and expansive industrial policy as it “explicitly targets a range of specific sectors and steps up the resource commitment to those sectors.”21 This is a basic feature of industrial policies and not of innovation policies, which generally do not target specific industries. Consequently, Naughton argues that the IDDS is mislabeled and should more accurately be called a technological upgrading development strategy.

“The IDDS outline defines three stages for achieving China’s overall modernization by the middle of the twenty-first century. The first step is for China to become an “innovative country” by 2020. This means establishing a robust innovation-friendly governance regime with improved intellectual property protection, better incentives, and a comprehensive set of policies and regulations. The outline calls for annual R&D expenditure to reach 2.5 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) by 2020, which it came close to actually achieving.

“The IDDS outline defines three stages for achieving China’s overall modernization by the middle of the twenty-first century. The first step is for China to become an “innovative country” by 2020. This means establishing a robust innovation-friendly governance regime with improved intellectual property protection, better incentives, and a comprehensive set of policies and regulations. The outline calls for annual R&D expenditure to reach 2.5 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) by 2020, which it came close to actually achieving.

“The second stage is for China to “move to the forefront of innovative countries” by 2030 (subsequently revised to 2035). This requires the country to join the top tier of advanced industrial and innovation economies, with China becoming a global leader in select areas. Annual R&D expenditures should reach 2.8 percent of GDP by 2030. The third and final stage is to become a “strong global innovation power by 2050,”

“MOST [Ministry of Science & Technology] minister Wan Gang (万钢) pointed out at a press conference in March 2015 that nearly forty government departments and one hundred planning channels were dealing with S&T project management, which has “caused duplication and closures, affecting efficiency. The problem of resource fragmentation is prominent.” MOST only had control of 20 percent of the total state S&T budget.

“The State Council embarked on a far-reaching reform of the S&T funding system in 2015 to tackle many of the problems outlined by Xi with the issuance of the Management Reform Plan of Central Science and Technology Finance Plans (Special Items, Funds) (中央财政科技计划 (专项、基金等) 管理改革方案, Zhongyang Caizheng Keji Jihua (Zhuanxiang, Jijin Deng) Guanli Gaige Fangan). One of the plan’s most important reform measures was to consolidate several hundred existing special S&T plans and funds into five comprehensive programs.”

CENTRAL COMMAND

If Wang Gan is indeed the hero of China’s lithium battery car industry, it is due to his battling within the bureaucracy to centralise command and control, very much in line with Xi Jinping’s centralisation of everything. The outcome is that IDDS is now embedded in Xi Jinping Thought, the official ideology all cadres must study and obey.

At the 18th Chinese Communist Party National Congress in November 2012, the moment Xi Jinping took full power, the vision of a techno-security state was revealed. Retiring leader Hu Jintao, in his final speech, introduced Xi Jinping’s agenda, including China’s new engine, the Innovation-Driven Development Strategy (IDDS), saying ““science and technology innovation provides strategic support for raising the productive forces and boosting comprehensive national strength and must be placed at the core of the overall development of the country.” Key goals of the IDDS were as follows:

- China must focus on indigenous innovation and elevate the capability to conduct original innovation, integrated innovation, and reinnovation through importation, digestion, and absorption.

- China should attach importance to systematic innovation, deepen reform in technological structures, push for close integration of S&T and economic development, and speed up construction of a national innovation system.

- The Chinese government will build a market-oriented system for technological innovation with enterprises playing the lead role and combining with industry, academia, and research institutes.

- China will improve its knowledge innovation system and strengthen basic research and development (R&D) in frontier technologies.

- China will seek to occupy a strategic vantage point in S&T development by pursuing major national technology projects, make breakthroughs in major technology bottlenecks, and speed up research, development, and the application of new technologies.”

At the time, this formal announcement was not seen, inside China or beyond, as anything special. For a CCP Politburo dominated by engineers and technocrats, these aspirations repeated themes common among central leaders. Outside China, it seemed to be an aspirational list, at a time China was widely seen more as a skilled copier rather than innovator.

It took Xi Jinping some time to consolidate his rule, eliminate rivals, and marshal the capital and the campaign strategy to actualise his vision of the fusion of party and state, fusion of civil and military, fusion of industry policy and technology, with the concept of security binding them all together.

PREDATORY EXTRACTIVISM?

China’s dominance of the full suite of post-carbon tech would not necessarily drive China to predate on its Tibetan backyard, as China has long had access to deposits of critical minerals worldwide. The further factor that tilts China to intensify extraction from Tibet is the drive by the richest countries to secure critical mineral supply for themselves, switching the sourcing and processing of critical minerals away from China.

Perverse outcomes, unintended consequences are common in real world decision making, and this is one. When the G7 rich nations club decides to de-risk its critical minerals flow, after decades of outsourcing it all to China as globalised efficiency, there are perverse outcomes, including predatory exploitation of the Tibetan Plateau.

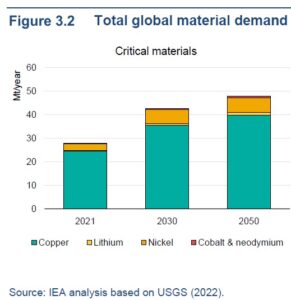

This blog is focussed on the globalised lithium trade, but the proposition above applies to copper as well, both in rapidly increasing demand due to the switch to “renewable” energy, both dominated by Chinese processing and manufacturing, both essential to all the tech needed to get the planet off its addiction to fossil fuels, both abundant in Tibet.

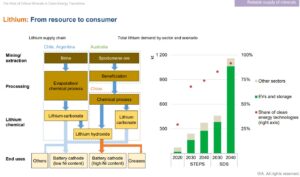

Right now, China has access to all the lithium it needs, for those lithium guzzling electric car batteries, whether it is salt lake lithium from Latin America, or rock lithium from Australia. China either owns the mines and refineries , or has long term contracts to be first in line from what is shipped right across the Pacific from Chile to China, or through the Indian Ocean and South China Sea from Western Australia.

Now the US, EU, Japan and Korea are gearing up to change all that, and have allocated billions to achieve their de-risking goal. Since lithium demand is forecast to grow rapidly, there may soon be tight competition for who owns the mines, who does the mining, and where the lithium processing is done, even if it does cost billions to disentangle the commodity chains of globalisation.

For Tibet, this decoupling of the critical minerals supply chain could have deep impacts, especially in mountainous eastern Tibet, where the rock lithium is, in districts China has never found much use for until now.

Having set the scene, now for the evidence.

Madonna’s material girl is by now four decades older. Four decades ago China was feeling for each stone as it crossed the river from command and control to capitalism. In the 1980s only the World Bank was willing to invest in China. Central planning was bankrupt. Now China proudly proclaims mastery of each one of the statisticians’ 41 industrial categories, 207 industrial subcategories and 666 industrial subsubcategories of manufacturing.

A major component of the second industrial revolution, ushering in the American 20th century, was the division of labour, replacing skilled craftsmen with interchangeable, lesser paid assembly line workers. That division of labour went global in the 1980s, closing American factories, relocating production to China and cheaper labour. For decades this was celebrated as the efficiencies of globalisation and scale.

Now the actual price of globalisation is all too apparent, but it may be too late to do much to reverse it. China is on the brink of nailing it all, even if it means sourcing lithium from Tibet rather than Chile, Argentina or Australia, as the newly discovered rock lithium deposits of Tibet await.

China’s two biggest electric vehicle brands, BYD and Tesla, rely on lithium extracted from Tibet as the foundation of their corporate expansion into markets worldwide. Lithium, classified almost everywhere as a critical mineral, is meant to be the gateway to a clean, green, decarbonised future; but in reality its’ accelerating extraction from Tibet is deeply troubling.

BYD and Tesla compete vigorously, and deploy different corporate strategies, including in Tibet, where BYD has long relied on salt lake lithium from the alpine desert of far western Tibet; while Tesla turns to rock lithium from the rugged landscapes of subtropical eastern Tibet.

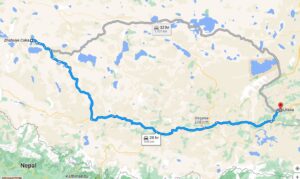

BYD has long boasted of its exclusive right to extract from Chabyer salt lake, which is far closer to India than to lowland China; while Tesla’s mega factory in Shanghai depends on major Tibetan lithium miners for access to the spodumene rock lithium of Kham, in the Tibetan autonomous prefectures of western Sichuan.

Demand is soaring, a scramble within China to claim mining rights to Tibetan mountains is under way, hot speculative money is pouring in, fortunes will be made. China’s party-state engineered and nurtured this boom, but fears it might become a destabilising bubble. Yet China, at the highest level, does want to be the winner of this Fourth Industrial Revolution, the global master of all the tech of a decarbonising world. Through decrees, incentives, subsidies and policy statements by Xi Jinping, China intends to dominate, as surely as Great Britain dominated the first, and the US the later industrial revolutions.[4]

In June 2023 a high level gathering in Chengdu announced the new strategy is under way, “focusing on national resource security needs, strategic mineral resource development, oriented to solve key technical problems, integrating resources, multidisciplinary cross research and development, promoting technology engineering.” This wording is uncannily similar to the US-led critical minerals secure supply plan. The new national policy is called the New Round of Strategic Action for Mineral Search and Breakthrough, 新一轮找矿突破战 略行动. with China’s Ministry of Natural Resources setting up a Strategic Mineral Comprehensive Utilization Engineering Technology Innovation Centre, in charge of implementation.

This intensifying securitisation of Tibet is on the orders of Xi Jinping. “It is a practical action to implement the spirit of General Secretary Xi Jinping’s important instructions on ensuring the security of national energy resources. It is a key deployment to maintain the stability of the industrial chain supply chain, ensure the security of national energy resources, and prevent the risk of recession in the international economic cycle. It is a support for the new era and new journey. The country’s major strategic needs and practical measures to build a new development pattern.” [5]

The decisive moment was in late 2022, just when China threw off its pandemic restrictions: “The Central Economic Work Conference held in December 2022 emphasized strengthening domestic exploration and development of important energy and mineral resources and increasing reserves and production, accelerating the planning and construction of a new energy system, and enhancing the national strategic material reserve guarantee capacity. This has pointed the way forward and provided fundamental guidelines for the comprehensive implementation of the new round of strategic actions to find and breakthrough in mining.”

Now that the internal combustion engine is so yesterday, electrification is everything, and China already has created market dominance in PV solar, wind turbines, hydro dam construction and the power grids that connect them all to distant industrial users. If China can now dominate electric vehicles as well, it has the full suit, a lock on the future.

STATE CAPITALISM EVOLVES

This is a new moment for state capitalist developmentalism ideology and its implementation by a party-state the pushes investors to capitalise new electric vehicle (NEV) companies. Maoist command and control is gone. Now investors are nudged by IPO listing eligibility rules into AI, high tech and NEVs. As a result Xi Jinping gets to be champion of the next industrial revolution, master of the universe, timelord.

Financial Times explains: “President Xi Jinping is intent on boosting investment into sectors that fit with his priorities for control, national security and technological self-sufficiency, and is using stock markets to direct that capital with the aim of reshaping China’s economy. Clearly there’s a policy incentive to direct capital to areas that are deemed strategically important to China. The new approach centres on the top-down co-ordination of resources from government, industry, finance, universities and research labs to accelerate technology breakthroughs and help reduce China’s reliance on the west. But making markets serve the state’s priorities is a major departure from past administrations and the pro-market position initially espoused by Xi after he became party leader in 2012.

“Roughly a year ago, Xi told top leaders assembled in Beijing that China needed to mobilise a “new whole-nation system” to accelerate breakthroughs in strategic areas by “strengthening party and state leadership on major scientific and technological innovations, giving full play to the role of market mechanisms”. Key to that shift, says Kinger Lau, chief China equity strategist at Goldman Sachs, is getting companies in sectors such as semiconductor manufacturing, biotech and electric vehicles to go public. With stock market investors backing them, they can scale up and help drive the growth in consumer spending needed to fill the gap left behind by China’s downsized property market.

“Xi’s administration was already channelling hundreds of billions of dollars from so-called government guidance funds into pre-IPO companies that served the state’s priorities. Now it is speeding up IPOs in Shanghai and Shenzhen. Xi’s stated plan to give “full play” to the role of markets comes with an important rider: those markets will take explicit and frequent direction from the party-state.

“They’re listing the firms and they’re making them attractive because they have government subsidies or enjoy low taxes,” says Thomas Gatley, an analyst at Gavekal Dragonomics. “The strategy is market driven, but not fully market driven — the government’s thumb is on the scale.” Xi’s stated plan to give “full play” to the role of markets comes with an important rider: those markets will take explicit and frequent direction from the party-state. “Xi Jinping wants all these things, but he wants them in a particular way because self-sufficiency and political control are very important to him,” says Fraser Howie.”

LOCATION, LOCATION, LOCATION

For decades, the salt lakes of the Tsaidam basin in northeastern Tibet were the obvious location for large scale extraction of lithium, which had been dumped as a waste byproduct after the extraction of potassium, magnesium and sodium salts, all more valuable than lithium. Then lithium rocketed in price, but extraction, to a sufficient level of purity, has remained frustratingly close, yet has not happened.

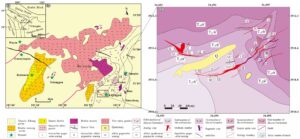

Spodumene rock lithium was so evidently a poor second, little effort went into exploring. That all changed in this pandemic decade. China’s Ministry of Natural Resources annual English language survey for 2021 says: “A new large spodumene deposit in Jiada mining area on the periphery of Ma’erkang [Markham] in western Sichuan was newly discovered.”[6] By 2022, intensive research was under way.[7] Chinese names were assigned to these remote locations at 3540 to 3830 metres altitude. Excitement grew when small concentrations of rare earths were found nearby.[8]

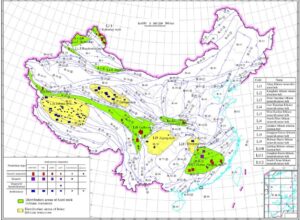

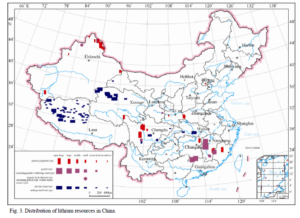

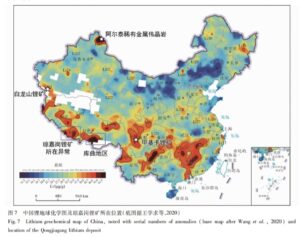

By 2023, China’s assessment of its lithium resources had changed so much that a new overview, written by a team of 16 geoscientists, put rock lithium first.[9] Their opening words reflect a dramatic shift: “China is rich in abundant lithium resources characterized by considerable reserves and a concentrated distribution of metallogenic zones or belts, with proven reserves of 4046.8×103 tons” of lithium dioxide. That’s over 4m tons. Until very recently it was a well-known truth that China has quite limited sources of lithium. Now in 2023 pure lithium within China’s borders has been upped to 4.047 million tons.

“The major lithium deposits in China are distributed in provinces and regions such as Qinghai, Jiangxi, Sichuan, Tibet, and Xinjiang. The study aims to serve as a guide for the future prospecting of lithium deposits in China.” Of the 4.047 million tons of lithium in deposits in China, 3.655 m tons are in the Tibetan Plateau. That is about 90 per cent.

Conventional wisdom worldwide is yet to catch up with this intensification of lithium locations across Tibet. Electric car marketers and critical minerals analysts continue to report that China has little access to lithium within its borders, yet dominates lithium processing. In reality, once it became clear lithium of the major salt lakes of northern Tibet was so near yet far, impossible to separate to a purity required for batteries, central leaders turned to their geoscientists to find rock lithium deposits, and they found plenty.

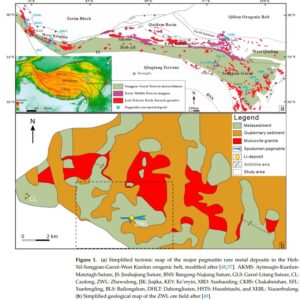

There are now substantial spodumene rock lithium deposits identified in many scattered districts of Tibet, their discovery aided by high tech satellite camera imagery rather than laborious foot patrols. A 2023 report in a journal dedicated to detection by satellite says: “these metallogenic belts are generally higher elevations, cold, hypoxic with harsh environmental conditions, raising great difficulties during field investigation. Therefore, it is necessary to develop a more efficient and cost-effective exploration method specifically for Spud [spodumene].rich pegmatite deposits. The rapid development of remote sensing technology has made it possible. Pegmatite deposits are typically characterized by their small outcrop area and lack of prominent regional alteration features, making it challenging to apply established HRS [hyper spectral remote sensing] exploration models. Due to the small width of the pegmatite dykes and the lack of typical alteration zones, the ability of HRS in the exploration of Li-rich pegmatite deposits remains to be explored. Therefore, the direct detection of Li-bearing pegmatites using hyperspectral data remains a subject that requires verification, particularly considering that the width of most pegmatite dykes is often smaller than the spaceborne sensor’s spatial resolution.”[10]

The Zhawulong spodumene pegmatite deposit is geographically located at the junction of Sershul [Shiqu in Chinese]in Sichuan Province and Thridu [Chindu or Chengduo 称多县]County in Qinghai Province. Sershul is a district chosen by Tibetans as suitably remote, peaceful, suitable for intensive mind training inner transformation programs, much to China’s security state alarm. In the 1990s it seemed the right place for a large encampment of sincere mind training practitioners, on the periphery of three provinces: Sichuan, Qinghai and Gansu. Now the lithium rush has caught up with them.

SALTING THE MINE, MINING THE SALT

Although China’s attention has shifted away from the massive salt lakes of the Amdo Tsaidam basin, and towards rock lithium, intensive research seeks the elusive breakthrough that will at last enable complete separation of lake lithium from the other metal salts it has strong affinity with.

While the Tsaidam salts remain unusable for battery grade lithium, there is one other Tibetan region where salt lake lithium extraction is much more straightforward. In the alpine desert of far western upper Tibet are salt lakes where separation is much easier. As in the brine of the salt lakes of Chilean and Argentine high deserts, all it takes is a bit of patience, to bulldoze evaporation ponds which, over two years, concentrate the salts, which fall out of solution one after the other, finally leaving the yellowish lithium brine naturally separate from its friends.

The only problem is that Tibet’s far west is much closer to India than China, a full 1000 kilometres west of Lhasa, a further thousand kms to the factories that make batteries. That is not as far as shipping Chilean lithium across the Pacific, but it’s all overland by truck, very energy intensive.

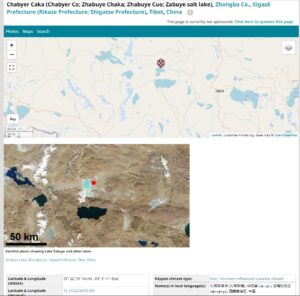

That was no barrier to BYD and its strategic investor Warren Buffett, whose long ownership of BYD stock today legitimates BYD’s surge to top lithium powered car maker globally. It was Buffett’s shrewd purchase of BYD shares back in 2008 that provided BYD capital sufficient to exploit the Chabyer Tsaka salt lake. Chabyer was just the first of 24 salt lakes of western Tibet to be identified as rich in lithium, extractable through simple evaporation Extraction has grown, despite the logistical difficulties of the very remote locations, and now is around 30,000 tons a year, far from fulfilling China’s hunger.

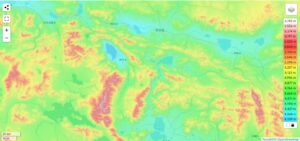

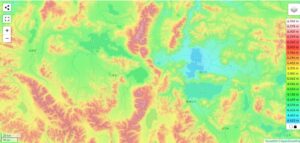

Lakes in Zone I, coloured pink, are easiest to extract pure lithium by letting the sun do the work of evaporation. Source: https://ars.els-cdn.com/content/image/1-s2.0-S1674987122001384-gr1_lrg.jpg Tao Ding, Lithium extraction from salt lakes with different hydrochemical types in the Tibet Plateau, Geoscience Frontiers, Volume 14, Issue 1, January 2023, 101485

The earliest, initially sporadic efforts at locating and extracting Tibetan rock lithium were at Jiajika, near Markham. This ore field is now at the centre of the lithium rush, even those narrow dykes of crystallised lithium in Tibet are still elusively hard to find, with no certainty that surface outcroppings signify deeper veins below. The only way to be sure is drill, baby, drill.

This means the rock lithium boom in Tibet is only now scaling up. If this boom, based on long term lithium price, supply and demand forecasts holds up, we can expect many more lithium extraction enclaves, in several of the Chinese provinces into which the Tibetan Plateau has been fragmented.

As well as the cluster of rock lithium deposits near Markham, there is a major cluster in Sichuan province, near Barkham, which China calls the Ke’eryin ore field. There is Zhawulong to the northeast of Yushu town [Jyekundo traditionally in Tibetan]. China’s primal dream of Tibet as a treasure house is coming true, as never before.

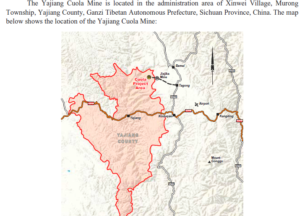

Not far away is Dechenongba, just beyond Qinghai Yushu prefecture, and in Sichuan, where the big guys in rock lithium extraction are moving in, with PR hype to match: “China’s leading battery manufacturer CATL is continuing to increase its reserves of lithium mine resources. According to an announcement released on November 28,2022, it became the first investor in the bankruptcy and reorganization of Sinuowei Mining in Sichuan Province, aiming to control the enterprise with an annual output of 300,000 tons of lithium and enhance its supply chain support capabilities.

“Sinuowei Mining now owns the prospecting rights for detailed investigation of the Dechenongba Lithium Mine and Quartzite Mine in Yajiang County, Sichuan. The Dechenongba site is categorized as a “super-large” lithium mine, capable of achieving a production scale of 1 million tons per year. The annual production capacity of lithium concentrate can reach 300,000 tons after production.”

ZOOM ZOOM: PEDAL TO THE HEAVY METAL

At the heart of corporate strategy of BYD and Tesla, and the many hundreds of Chinese electric car makers, is a clear recognition that the best sellers will be cars that accelerate sharply, and clock up plenty of kilometers before needing a recharge. Electric cars are quiet, no throaty vroom vroom. But they must go zoom zoom, which satisfies the egos of the mostly male buyers. Both the fast acceleration and the long range require big, heavy batteries laden with lithium. That is where Tibet comes in.

BYD’s top of the range model is badged the 3.9s, a chrome plated boast that it accelerates from still to 62 mph in 3.9 seconds, zoom zoom.

Never before has Tibet been such a prospective profit centre for China. Despite heavy industrialisation of the Tsaidam Basin of northeastern Tibet, decades of rapacious logging of the forests of transHimalayan south eastern Tibet, rapidly growing extraction of copper, and the almost exhausted extraction of chromium from southern Tibet, none of these booms (and busts) compares with the lust for lithium.

Lithium fever runs hot in China, undeterred by a mid-2023 cooling in lithium prices from their nosebleed peaks in late 2022. If you are into making money fast, and you aren’t in possession of mining rights in Tibet, you are a nobody still making boring stuff like iron and steel.

Selling Tibet to Chinese investors has been gamified for maximum viewer excitement, and lunatic pricing. Like a game show, the sale of a mining right, or just an exploration right, is done online over a week, as bids come in and excitement builds. The listed reserve price is set low, to exaggerate the extreme price offered by the ultimately successful bidder. Such is the appetite to own a slice of Tibet it is not uncommon that 11,000 bids are registered.

“The auction for the Jiada lithium mine closed earlier this week with the equivalent of around US $580 million – 1,300 times more than its starting price, according to data from the Sichuan Public Resources Trading Centre, administered by China’s government. Last week, an auction for the Lijiagoubei lithium mine, also in Sichuan, closed at more than 1,700 times the starting bid.” Noticias Financieras 17 August 2023.

SICHUAN BOOMTIME

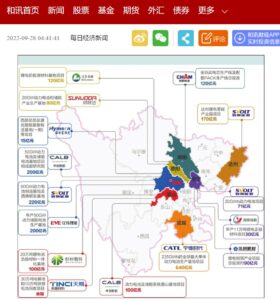

The deep inland province of Sichuan is shaping up to be the centre of a new industry based on rock lithium extraction from its mountainous Tibetan hinterland. On the basis of exclusive access to the hard rock lithium deposits of eastern Tibet, Sichuan now has elaborated plans to become the powerhouse of an entire industrial value chain that starts with rock extraction and ends with the manufacture of lithium battery powered care, which are then exported to Europe overland on a trans Eurasian railway currently under construction across eastern Tibet.

Sichuan as powerhouse is not new. Sichuan was designated decades ago as a major source of hydropower generation for export to China’s long belt of distant coastal factories. What is new is that Sichuan, a laggard province on most human development indicators, now wants to be much more than a source of raw materials and electricity for use elsewhere; it wants to do the value adding in the province, and capture the profits.

In some ways comparable to inland Uttar Pradesh in India, Sichuan is China’s most populous province, but lacks ports, and immediate access to global shipping. Sichuan is a long way upriver on the Yangtze, and was meant to gain access to heavy shipping by the damming of the Three Gorges. In the decades since the dam was built the promise of a river road to the sea has largely failed to materialise. Not only does that deprive Sichuan of export opportunities, it also means competitive disadvantage compared to coastal provinces in accessing imported raw materials, such as China’s huge purchases of salt lake lithium from Latin America and now rock lithium from Australia. So a new source of rock lithium within Sichuan is a revolutionary opportunity to do the whole upstream to downstream chain, from rock mining to electric car manufacture.

Sichuan acquired its Tibetan uplands only with the revolution of 1949, and by area constitute 42% of the province. Mao’s revolutionary regime wasn’t revolutionary in its definition of provinces and their boundaries, largely leaving previous carvings of fiefdoms intact. Sichuan is the exception. Under the previous regime, eastern Tibet was a separate province, carved off from Tibet by conquest, called Xikang. Republican China struggled to Sinicize Xikang and largely contented itself with extracting tax from the Tibetans. The rugged uplands of Kham and Amdo, forcibly separated from the rest of the Tibetan Plateau, had little connection with the hot and humid valleys of Sichuan, other than the trade in Tibetan horses for military use, with the teas of Yunnan and Sichuan going back up into Tibet.

Revolutionary China abolished Xikang, making it the backblocks of Sichuan. For decades Sichuan found little use for its western uplands, beyond predatory logging of the forests of the steep slopes, sliding tree trunks down into the many tributaries of the Yangtze to be floated down to the Sichuan basin by gravity. After disastrous floods in 1998, made much worse by hillslopes denuded of forest cover, logging was halted. Sichuan and central leaders turned to hydropower, helped by substantial loans from the World Bank, to dam Tibetan rivers, mostly where they exited the plateau, where valley walls are still steep enough for dam placement, but not so far upriver as to be too costly to build.

Other than timber and water, Sichuan has found little it can achieve in its Tibetan rump, until recent years, when rock lithium extraction quickly became profitable.

The population of Sichuan (including Chongqing municipality) is 116 million, densely concentrated in the lowlands. Tibetans of the two prefectures that used to be Xikang province, Amdo Ngawa and Kham Kandze are 823,000 and 1.1 million respectively. Fewer than 2 million among a total population of 116 million, in a region with two massive cities gradually fusing into one, Chengdu and Chongqing, both of them major manufacturing hubs, both keen to replicate China’s menu of industries in all categories. Being two fifths of Sichuan by area doesn’t count for much when by population you are less than two per cent, technically incorporated into Sichuan but effectively still an upcountry barrier beyond the frontier.

These are compelling reasons Sichuan looks upstream with greed aforethought, and depicts its extractivism as a civilising missions, bringing modernity, development and urban services to remote, poor, backward prefectures.

Despite similarities, densely populated Uttar Pradesh agreed to hive off its mountainous uplands, which became the state of Uttarakhand in year 2000. Now that rock lithium is found in upland of Sichuan, no way would the province let its outposts be free.

[1] Tai Ming Cheung, Innovate To Dominate: The Rise of the Chinese Techno- Security State, Cornell, 2022, 18

[2] Levi Tillermann, The Great Race: The Global Quest For The Car Of The Future, Simon and Schuster 2015

Akshat Rathi, Climate Capitalism: Winning the Global Race to Zero Emissions, Hachette, 2023

[1] Reinhold Niebuhr, Discerning the Signs of the Times (New York: Scribner’s, 1946), 72

[2] Keyi Tang, Yingjiao Shen, Do China-financed dams in Sub-Saharan Africa improve the region’s social welfare? A case study of the impacts of Ghana’s Bui Dam, Energy Policy 136 (2020) 111062

[3] Hao Zhou, Wenqian Qiu, Ke Sun, Jiamiao Chen, Ultra-high Voltage AC/DC Power Transmission, Springer, 2018, 1490 pages.

[4] Qiuyi Wang, Jai S. Mah, The Role of the Government in Development of the Electric Vehicle Industry of China, CHINA REPORT 58 : 2 (2022): 194–210

[5] 是落实习近平总书记关于保障国家能源资源安全重要指示批示精神的实际行动,是维护产业链供应链稳定、保障国家能源资源安全、防范国际经济周期衰退风险的关键部署,是新时代新征程上支撑国家重大战略需求、构建新发展格局的务实举措。

[6] Ministry of Natural Resources, China Mineral Resources 2021, Geological Publishing House, 3

[7] Xin Li et al.,

Geochronological and geochemical constraints on magmatic evolution and mineralization of the northeast Ke’eryin pluton and the newly discovered Jiada pegmatite-type lithium deposit, Western China, Ore Geology Reviews 150 (2022) 105164

[8] Zhang Wei, The C-H-O Isotopic Composition and Significance of Spodumene for Redamen Pegmatite Type Rare Metal Deposit in Western Sichuan, 川西热达门伟晶岩型稀有金属矿床锂辉,C-H-O 同位素组成及意义, 矿产综合利用2023 年2 月Multipurpose Utilization of Mineral Resources Journal

[9] Bo Zhang et al, Geological characteristics, metallogenic regularity, and research progress of lithium deposits in China, China Geology 5 (2022) 734−767, downloadable from http://chinageology.cgs.cn/en/article/doi/10.31035/cg2022054

[10] Wenqing Ding et al. Lithium-Rich Pegmatite Detection Integrating High-Resolution and Hyperspectral Satellite Data in Zhawulong Area, Western Sichuan, China, Remote Sensing, . 2023, 15, 3969. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs15163969, freely downloadable: https://www.mdpi.com/2072-4292/15/16/3969