TIBETAN EMPLOYMENT IN NATIONAL PARKS ཡུལ་དང་དུས་ཀྱི་རྣམ་འགྱུར་ལ་བརྟེན་ནས། བོད་ལ་ལས་དང་མ་རྩའི་དོན་ལ་བརྟག་པ༎

Blog one of three on the fate of Tibetan nomads, frogs, green iron rice bowls and highland clearances

(This blog is an expanded version of a presentation by Gabriel Lafitte to the Paris seminar of the International Association for Tibetan Studies, July 2019)

SECURE STATE EMPLOYMENT FOR SPECIALISTS IN LIVING OFF INSECURITY

Li Xiaonan, head of the Sanjiangyuan National Park says: “after living in the hardships of the past ecological degradation, Sanjiangyuan herders now have an ‘ecological bowl’ and ate the ‘green rice’, tasted the sweetness of protecting the ecological environment.”[7]

Today the iron rice bowl is overtly back, in this new iteration rebadged as the green rice bowl, a guarantee to every remnant drogpa nomad family of Yushu and Golok prefectures, that one family member now has a job for life, employed by the Sanjiangyuan National Park. The guarantee is explicit: one state employee per family, not more nor less. A year prior to the 2020 official launch of the Sanjiangyuan National Park the number of local Tibetan staff to be employed is precisely 17,211.

Many are already employed, and can already be seen in video docs online, engagingly sharing with us their joy at being out on the range, on their motorbikes, protecting wildlife. It all looks so good. This is much more sophisticated than China’s usual clunky propaganda, more plausible, more like the win/win eveyone hopes far.

It has a dark side: the ongoing, accelerating exclusion of more and more drogpa nomads from their pastures, in the name of national parks and wildlife protection. And the newly employed green rice bowlers are at the heart of the state’s machinery of exclusion and depopulation.

How to tell such a confusing story? Why would anyone doubt the word of a handsome Tibetan ranger telling a young English woman the delights of wildlife ranger work, even though it comes from China Intercontinental Communications Centre, CICC, now partnering with National Geographic and al Jazeera to get its docos into the mainstream?

Employing Tibetans doesn’t look at all like depopulating Tibet, so we need to wind back to the iron rice bowl days, meaning not only a guaranteed state salary but better access to health care and a pension after retirement, security to the grave, provided directly by the state.

This return of the almost forgotten iron rice bowl is a master stroke by a state that, in contemporary China’s unique fusion of state capitalism, retains dirigiste allocative power and a highly centralised capacity to redistribute. As a metaphor, the green rice bowl is immediately understandable to livestock producers accustomed to living off uncertainty, but increasingly uneasy with their peripheral position in a glittering urbanised world instantly accessible on their mobile phones.

This recursion is thus welcome, a return of certainty, and the 17,000 jobs allocated for Tibetan staff resident in Sanjiangyuan will be keenly sought, among the 72,000 herders deemed eligible to apply.

PRELUDE: MAGNETISED BY THE IRON RICE BOWL

In the revolutionary decades (1949 to 1976) the iron rice bowl, tiefanwan, connoted a state bent on industrial mastery, with iron and steel manufacture the highest priority. It was the ultimate and universally understood symbol of security for life, the end of famine, the arrival of a people’s republic, in which the people own everything.

The green rice bowl is overtly about wildlife protection and poverty alleviation, less overtly about urbanising drogpa. Urbanisation has replaced the walled compound enclave, as revolutionary push is replaced by urban pull. The privileged few who gain green rice bowl employment by the State Forestry and Grasslands Administration, will deploy daily from compounds, while their relatives will be encouraged, sometimes compelled, to depopulate the rangelands so the land of Tibet can become pristine grassland wildernesses, patrolled by the one family member remaining, with green rice bowl status.

In these ways the state achieves several objectives. It raises the cash income of drogpa families, fulfilling the pledge of central leaders to entirely eliminate all poverty, even in “contiguous destitute areas” 个集中连片特困区贫困 by 2020; it brings the state back in as guarantor of nationwide water provision, wildlife protection, biodiversity conservation, climate change mitigation, carbon sequestration, carbon market product creation, land degradation neutrality. Above all, it establishes sovereign state power as the active agent in command of the territorialised pristine grassland wilderness of eastern Tibet.

NATIONAL PARKS AS NATION BUILDERS

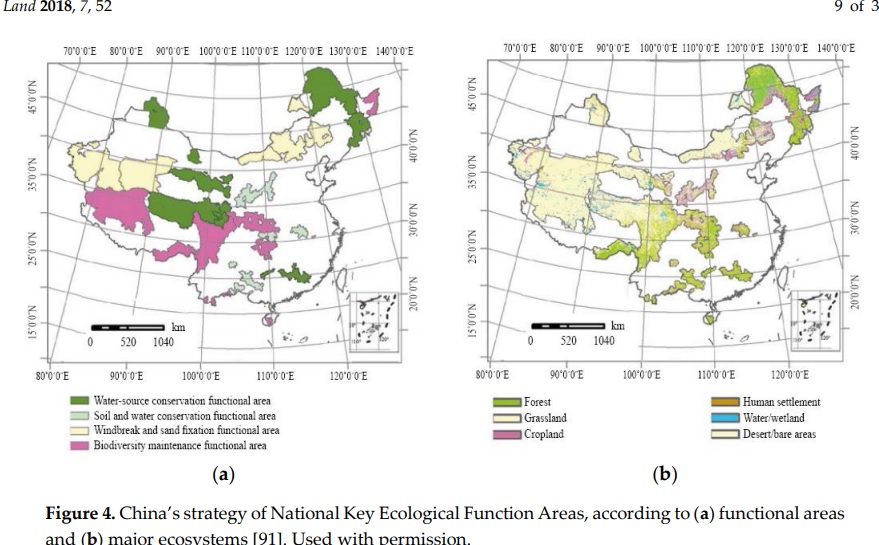

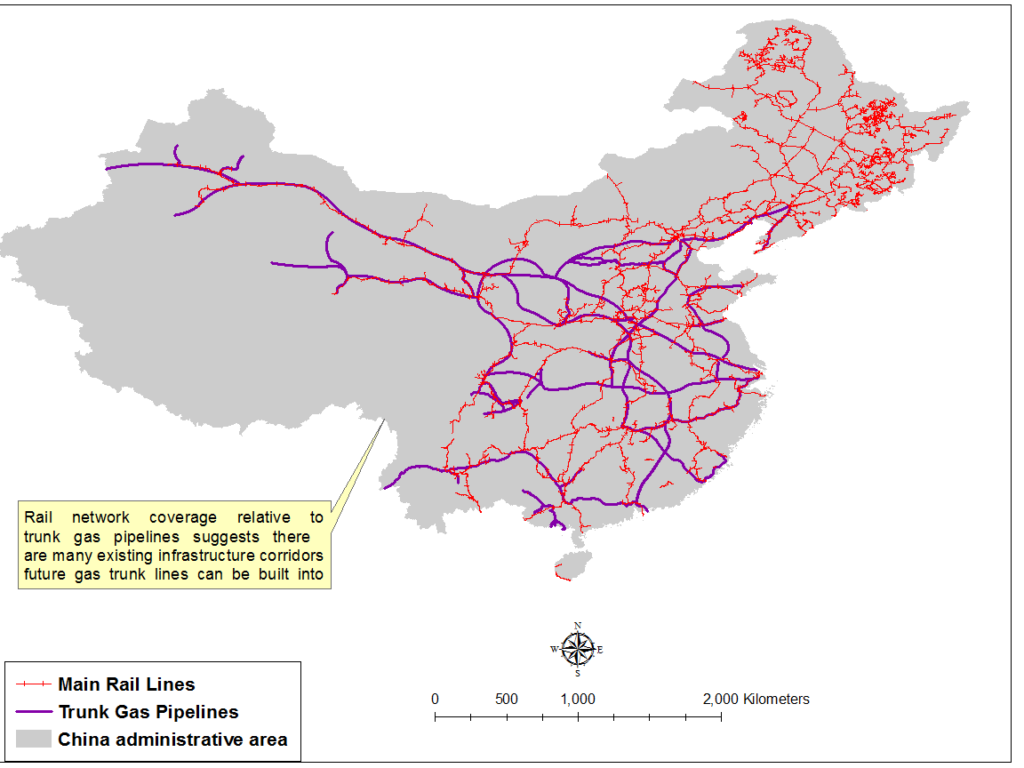

Never before has the geo-body of Tibet, which was traditionally stateless, been so deeply inscribed by nation-building state power, neatly partitioned by a rigid zoning system into an upper riparian zone designated exclusively for provision of environmental services, and a mid riparian zone, in Amdo and Kham, zoned for economic production of hydropower and water for industrial and urban consumption below.

This transformation achieves its apotheosis in the new system of national parks stretching across the Tibetan Plateau, about 30 per cent of the Tibetan sky island, which constitutes one quarter of the PRC geo-body.

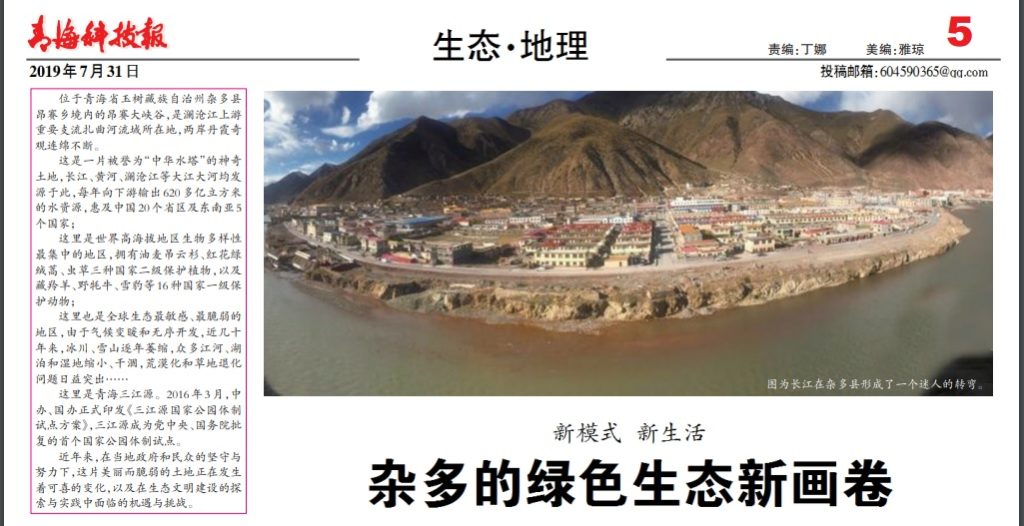

Source: Qinghai Scitech Weekly, 31 July 2019

In the recent past, the declaration of nature reserves and other categories of protected areas, notably wetlands, has been criticised as “paper parks” existing mostly as administrative categories, with little investment in actual biodiversity conservation management.

The new national park system is different. It comes at a time when China is not only much wealthier, it’s core goals now look beyond industrialisation and the primitive stage of accumulation, and China is keen to establish its credentials as the builder of an “ecological civilisation.” Previous protected areas were under provincial control, the national parks are indeed national, under central control, and bound up with China’s national reputation as exemplary global agent.

The new approach is better funded, more comprehensive in its interventions, more extensive in its reimaginings of landscape management, and more sophisticated in its recourse to ”top-level design”, derived from systems engineering. Part of this new sophistication is to go beyond the binary opposition of livestock production versus grass production, the famous Marxist dialectic of “the contradiction between grass and animals.”

The new approach, partly prompted by the suggestions of international partners, is more inclusive, less inclined to zero/sum exclusions. Now the new slogans speak of the “endogenous enthusiasm of the herder masses” to be mobilised, under state management, to do the actual work of park patrolling, gathering data on species numbers, and picking up rubbish. This endogenous enthusiasm is the basis of the green rice bowl guarantee of state employment, and implicitly, the loyalty of the 72,000 family members of whom 17,211 are to be employed, to the benevolent state provider of the green rice bowl.

This is enormously attractive, at a time when pastoral production remains as risky as ever, perhaps riskier as climate change accelerates, and city life appears seductively attractive, over the horizon yet instantly legible on the mobile phone everyone now has.

Tsering Bum, in a recent book on drogpa life, tries to explain to his friends why he wants to live among the nomads: “I made many friends while living in Ziling (Xining) and by 2015, many had worked in the NGO sector for years. When we met to catch up and I told them that I wanted to live in a rural community for the next year or two, their common reaction was that without internet access, I would be so bored that, within two weeks, I would probably give up and return to Ziling. Many Tibetans I know are like others living in China today – they view city life as highly desirable. It was easy to discuss my plans with friends in the NGO sector, owing to our shared interests and backgrounds. Many I interacted with thought that I should work in a city or, even better, work in a government office in order to have an “iron rice bowl” – job security for life. I understand this reaction. Economic development has facilitated and driven urbanization, creating ‘rural’ and ‘urban’ as binary opposites. Many in China are convinced that the city is the space for the civilized and developed, whereas rural areas are symbolic of backward, uncouth people. The goal then of higher education is to live and work in a city.”[1]

The green rice bowl is the arrival of city values in the countryside, the security of urban predictability, with a lifetime job guarantee, while still out on the grassland. It is deeply attractive, to those who have visited the cities, drawn in on the new tollroad expressways giving quick access to distant cities, but are yet to find an urban niche. Not only do the skills of pastoral production not translate to urban economy skills, in the urban context such skills are incomprehensible, and the risks routinely taken are deeply alarming to city folk.

Hence the endogenous enthusiasm of the herder masses to protect ecosystems, 着牧民保护生态的内生动力全面激发, Zhe mùmíng bǎohù shēngtài de nèi shēng dònglì quánmiàn jīfā to use a phrase attributed to Li Xiaonan, director of the Sanjiangyuan National Park Administration.[2] This is an advance on the standard “tragedy of the commons” narrative that blames nomads for degradation, refuses to admit evidence of successive past policy failures as alternative explanations for pasture degradation, and is amnesically silent on past efforts by drogpa to protect both wildlife and pastoral landscapes.

Is it the benevolence of central leaders to ascribe endogenous enthusiasm for doing the state’s work in remote landscapes? Is endogenous enthusiasm not only presumed by the state employer of drogpa, but prescribed?

We need to look more closely at what the job is, beyond cleaning tourist garbage, checking the camera traps for sightings of elusive snow leopards, and counting birds. The core duty of the green rice bowlers is to finalise the exclusion of most fellow drogpa nomads from the core Sanjiangyuan landscapes. This is why endogenous enthusiasm is mandatory.

Completing the highland clearance is the culmination of the official depopulation agenda, starting 2003 with the declaration of tuimu huancao, close pastures to grow more grass, as the ruling slogan. In fits and starts, as new quotas for nomad removals descend from above to local officials, and batches of deportees are recruited.

Well before 2003, Animal Husbandry Bureau officials were instructing drogpa to reduce herd size, to sell more animals for slaughter, to reduce grazing pressure on the limited land allocations awarded to each drogpa nuclear family. For decades this pressure on herds and herders reduced not only the total population on the land, but also reduced those who remained to poverty, as herd sizes fell below subsistence level, often in a seasonal disaster. The immiserisation of remaining nomads has been a major push factor in family decisions as to whether and when to give up the struggle, and move to the urban fringe.

In 2020, in the Sanjiangyuan National Park, this piecemeal process of depopulation becomes total. Until now, as several fieldwork ethnographers have reported, there has been some to and fro, as nomad families did move to town, yet could somehow keep their herd, in the hands of relatives, on lands not yet vacated. Sometimes young adults relocated to the concrete cantonments could slip past the surveillance cameras and return for the busy summer production season, to do the intensive milking, weaning, shearing and rotational grazing that generates an abundance of food and fibres for another year.

Until now, the total exclusion of all drogpa, and the complete cancellation of their mode of production, has not been absolute. Now, with the ceremonial opening of the Sanjiangyuan National Park in 2020, the final solution has arrived.

Employment of the green rice bowlers locks in and polices the end to such workarounds. For the first time, the police force out on the rangelands will be Tibetan, with knowledge of the land and its winding valleys where cattle can be kept away from official scrutiny. For the first time, policing will be by state gamekeepers whose knowledge of drogpa ways is unparalleled.

Economists, looking from afar, are tempted to call the green rice bowl state employment, a welcome return of the state, with social security guarantees of lifetime employment that lifts the poor out of poverty. The state is keen to see it that way, announcing that the monthly pay of 1800 RMB suffice to keep a family of five or fewer above the official poverty line.

Policing the rangelands, enforcing removals, ensuring there is no backsliding, no surreptitious herding, no ongoing pastoral production, no high country drifters left, are the core responsibilities of the green rice bowlers, policing the compliance of their own folks, in the core zones of the new national park.

This chimes well with the tropes abounding at the highest levels of the party-state. Now that the party’s disciplinary apparatus has formally taken over the state disciplinary machinery, the task of their combined capacity to police the entire forest of the Chinese population calling upon party members to be good “forest rangers” of the “political ecology,” which requires a clear understanding of the relationship between the so-called trees and forests. At the highest level, the rectifiers 整风 of the entire nation are forest rangers who uproot diseased trees that have no place in a healthy forest, while protecting those trees deemed suitable to remain. At the lowest level, the rectifiers of the rangelands enforce the closing of degraded pastures and permanent removal of the offending drogpa nomads, emptying the stage for the next act in the drama, the reintroduction of the tourist masses to partake of virginal wilderness.

In current CCP jargon setting drogpa to police drogpa is the phrase 主惩小恶, 以诫大恶, pay attention to punishing the small evils in order to forestall the larger evil. Now that the state has at last attained mastery over Tibetan landscapes, which took 60 years, the task is shifting from uprooting diseased trees to prophylactic prevention of any reversion to the bad old days when nomads were beyond the gaze of the state, inherently an affront to the panoptic scrutiny of the party-state.

POLICING THE HIGHLAND CLEARANCES

Tibetan exnomads loyal to this official agenda are employed not only as eco-inspector park rangers 立新增生态管护员岗位 but overtly as police enforcing exclusion. The park rangers sweep through the entire landscape doing three full patrols per month: “a total monthly comprehensive patrol protection zone for three times a month. During the period, several clues of ecological violations were discovered by the inspectors and reported to the relevant government departments.” They are the frontline, but not empowered to punish; that is the role of the police, who are also often Tibetans, ex-nomads who have decided to fall in line with the overwhelming power of the party-state.

The police must contend not only with drogpa evading mandatory displacement, but drogpa already removed to urban fringes seeking to return, now reduced to destitution because official algorithms allocate less than survival rations to them, because they had little land to begin with. The complex formulae awarding subsistence payments (transfer payments or payments for environmental services in official jargon) are based on previously granted, now cancelled, land tenure certificates. Those scanty rights to secure tenure were issued 20 to 30 years ago, long enough for a new human generation to come up. In some cases families grow beyond the capacity of allocated land to support them, pushing them into poverty, since customary drogpa processes for regularly re-assigning pasture according to need are no longer recognised by the state. Those squeezed into poverty by the rigid land allocation system are then further penalised on removal to urban fringes, because they had so little to be compensated for losing.

Official media acknowledge this double penalty for being poor: “the resettlement created several ‘ecological enclaves,’ which caused difficulties in terms of government management. Meanwhile, some of those who left did not have much grassland before, resulting in lower subsidies. Because of this, a small group of them have been trying to move back to the grassland. Moreover, conflicts over land still exist in natural preservation work, the Global Times reporter learned. For instance, Tanggula (Tanglha in Tibetan) town residents are currently in a dispute over grassland with the Hoh Xil preservation station.”

This presents the police with much work to do, both pushing remaining drogpa off their lands, and preventing desperately poor resettled drogpa from illicitly returning to their lands and livelihoods. Many of the police have been recruited from the earlier batches of the displaced, who have by now had 15 years on the fringes of Gormo, the Han Chinese petrochemical industrial city of Tibet, (Golmud in Chinese). They have seen the allocative, redistributive power of the authoritarian state close up, and decided to go with the strength.`

Official media give us a glowing portrait of a couple enjoying the new life, 500 kms from their traditional pasture high in the Tanglha Ri mountain range at the source of the Yangtze. She is now a cadre, he is a policeman. “Resettlement was an important part of the project. Over 55,000 herdsmen from 10,140 households abandoned the nomadic life and settled down in brick houses on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, according to the Xinhua. Aqie Jamo was one of them. She was resettled in Changjiangyuan village, 10 minutes by car from Golmud, the second largest city in Northwest China’s Qinghai Province. Aqie Jamo now works in the local town government. Her husband is a police officer. Every month, he spends 15 days in the Tuotuo River area in Tanggula, where Aqie’s family used to live. Aqie Jamo’s two children, who are 6 and 1, do not have to experience the harsh childhood their mother did. Every morning, Aqie Jamo drives her older child to school in Golmud city. ‘There are more social resources here, which make our lives easier,’ Aqie Jamo said. ‘Also, there is more oxygen.’”

Aqie Jamo (Gyalmo?) expresses her gratitude at being able to breathe the thicker air of Gormo, a sure sign the words attributed to her address the standard Han apprehensions, the thin air, never a problem for Tibetans, but always high on the Han list of reasons to fear Tibet. Also attributed to her is the comfort of life ten minutes by car from the urea, potash and PVC plastics factories of Gormo, which thicken the air further. Mentioned almost in passing is that her husband, a policeman, works back home on their former rangeland, 500 kms away, in a rotation of 15 days on duty 24/7, with 15 days a month off.

What does her husband do for that half of each month out on the Tanglha Riwo rangeland at 4700 m altitude, a high pasture indeed? The lawless days of Hui hunters and gold diggers exploiting wildlife and riverbeds with impunity are long gone, and this alpine desert landscape is close to being what China now calls “no-man’s land.” It seems the sole duty of a policeman on duty is to ensure all grazing ceases, even though the high-impact Qinghai Tibet Engineering Corridor, with its new expressway, bisects the Tuotuo/Tongtian (uppermost Dri Chu/Yangtze) as it crosses the Tanglha high passes. Aqie Jamo’s husband is at the forefront of tuimu huancao compliance enforcement. Grass trumps Tibetan livelihoods, and negates Tibetans as owners of their pasturelands.

Aqie Jamo’s unnamed husband is the frontline of nomad exclusion enforcement, recruited because he knows the land and its people, and is used to the hard life. He is just who the party-state needs, to uproot the diseased trees, the recalcitrant and recidivist nomads who still see their land as their only lifeline. He is the decisive closure of the Tibetan pastoral lifeway, cancelled by decree after 9000 years of sustainable and productive landscape curation.

This does not mean all nomads will soon be gone, Tibet is just too vast, and official policy in many areas supports ongoing pastoralism. The closure is most intensive in the core area to be declared Sanjiangyuan national park in 2020, around 150,000 sq kms, less than half the total area of the Sanjiangyuan protected area of 363,000 sq kms, bigger than Germany.

Sanjiangyuan is being rolled out in stages, over several years, with no announced timeline for full expansion to its planned full size. Exclosure of the pastoral mode of production has taken decades already, and will take more years, although the pace is accelerating.

What sort of life do exnomads have in the new concrete settlements?

The next blog in this series of three takes us into the lives of Tibetans

displaced by China’s nation-building agenda.

[1] ཚང_ཚ_རངིངི_འ_མ_Tsering Bum རང_ང_ཁམས ི ང ངོངོ བ བདོདོི_ིའ_གོག_པ_དང_ི_དོདོ_ི_ིའཇགིགི ེནེན__Guardians of Nature: Tibetan Pastoralists and the Natural World, Asian Highlands Perspectives, 2016

[2] Herdsmen become the main body of ecological protection of Sanjiangyuan, Qinghai Scitech Weekly 10 April2019 http://www.cnepaper.com/qhkjb/html/2019-04/10/content_1_4.htm