Blog three of three on Tibetan nomads, frogs, green iron rice bowls and highland clearances

INSECURITY AS THE MODE OF HUMAN EXISTENCE

Pastoralism worldwide is confined to drylands, which receive enough rain for grass to grow, but not forests. The drylands are between the desert and the arable. By definition, such lands are inland, often upland as well, as in Tibet, dependent on rain from distant oceanic sources, by definition environments of great uncertainty, precipitation unpredictable.

There is much to learn from the debates about pastoralism elsewhere, especially Africa, where urban elites govern the remote drylands, assuming those rangelands, at best, are unproductive and backward; at worst are exacerbating desertification and disaster. In recent decades these assumptions have been questioned by serious re-assessments, which suggest that traditional pastoralists not only make a living despite uncertainty but actually from uncertainty, by flexibly and quickly responding to unpredictable and changing circumstances, by mobility. Saverio Kratli calls this “living off uncertainty”,[1] which in Tibet could be said to be an art central to the drogpa mode of production. This China has never understood. Living off insecurity is fast losing its attraction. The green rice bowl means security, even beyond the working life, into retirement with support from a pension fund.

Today the pull of urban comforts and certainties is irresistible. The centralisation of schooling, health care, offices and shopping malls in cities makes a life of uncertainty and endless adaptability far less attractive. This is irreversible. The pull of urban life is strong. In recent years China closed 80 per cent of primary schools in Tibet, centralising access to schooling in bigger towns and cities. But the push is also strong, pushing drogpa from their land, cancelling what limited land tenure rights they had been granted, compelling the sale of livestock, emptying the land in the name of biodiversity conservation.

Tibetans weaving livelihoods from uncertainty did not separate into exclusive categories the wild and the domestic, human and animal, nature and culture; all had the same status, all were to be protected, which is what Tibetans continue to teach to children. It’s a nice video.

Tibetan attitudes to animals -wild and domestic- are explained by the scholar Peter Schwieger: “Although Tibetan language confirms that there is a clear categorical boundary between man and animals in Tibetan society, there is—unlike in Western societies—no strict ontological boundary between the two. This is on the one hand due to the animist worldview deeply rooted in Tibetan culture, but on the other hand also due to basic Buddhist concepts which explain animals as possibly one’s own forms of existence in previous or future lives. Moreover, as beings bound to the process of cycling through one rebirth after another, they are all considered as living beings to be liberated.”

The lamas remind anyone with ears that uncertainty is the human condition, it is all we have, we must adapt as appropriate to changing circumstances. Uncertainty, conditionality, impermanence, contingency, unpredictability are the realities of life, where causes and conditions combine and dissolve, each moment. To suppose we can control all risks is impossible, yet China is more determined than ever to govern all risk away by removing the drogpa nomads away from their landscapes.

TIMELESS NOMADS ENTER THE CITY & ENTER HISTORY

Yet many questions remain. It is the central state that has nationalised the territories constituting the new national parks, and it will expect active gratitude, loyalty and compliance from those it employs under green rice bowl guarantees. What is particularly unclear at present is whether the privileged 72,000 drogpa of the huge Sanjiangyuan National Park are to become the only pastoralists permitted to remain on the rangeland, and still engaged in the pastoral mode of production. Does tuimu huancao, the slogan since 2003, the closing of pastures to grow more grass, still hold sway? It seems so.

The master narrative has not changed. Degradation is still the driver of policy, and blame for degradation is still solely the fault of drogpa, even if they now do have an acknowledged endogenous enthusiasm for protection, under state direction.

If anything, the institutionalisation of National Parks as a system of uniform top-level design reifies these categories further. While Tibetans from Golok and Yushu are to be employed as rangers and field data collectors etc., Han Chinese are being recruited to staff Sanjiangyuan research institutes to aggregate the field data, key metrics such as water retention, degradation of grasslands, biomass gains, and biodiversity species abundance; all numerical grist for scientific management and further evidence of China’s mastery of modernity. The distinction between those entering history –the Tibetans- and the agents of ecological civilisation construction is precise.

The recent Global Times report[2] makes it clear that the “resettled” drogpa now housed on the outskirts of Gormo/Golmud, a long way from their customary Yushu pastures, have entered history and are no longer timeless: ”Aqie Jamo, 29, still gets frightened when she looks back on her childhood experience of herding sheep alone in the mountains. Once, when she was 7, she and her flock got caught in a storm, and all she could do was find a hole in the ground and hide inside it.

Aqie Jamo is the daughter of a Tibetan herdsman. At that time, her whole family lived a nomadic life.”

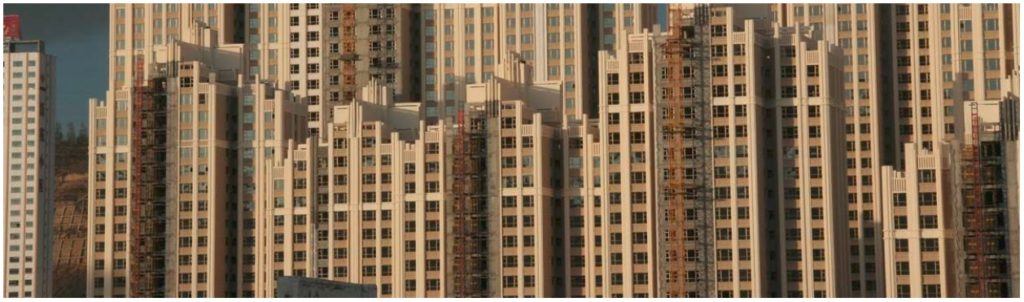

Now she and her policeman husband are exemplary citizens, with not only a horrifying past but a guaranteed rice bowl future as low level officials. They have entered history. Becoming civilised, acquiring human capital, learning the urban life, living in a high rise apartment with no space for animals, all propel the timeless uncivilised nomads onto the conveyor belt of history, a first step on the long journey to the inevitable goal of modernity with Chinese characteristics.

THE COMPOUND AND THE IRON RICE BOWL

When the modern developmentalist state arrived in Tibet, especially in the vast stateless pasturelands of eastern Tibet, pastoralists were amazed. The very first incoming instantiations of a distant power establishing force majeure authority over the grasslands was military. The violence of “liberation” is now well documented.

PLA soldiers, when not actively fighting, camped in compounds. This was familiar, even in remote pastoral valleys of Amdo, because expeditionary forces come equipped with supplies for their campaign and, if militarily successful, then dig in as an occupation force to prevent further outbreaks of conflict. Many areas of eastern Tibet not only have memories of past conquest centuries ago, by Mongol armies and by forces despatched from Lhasa, but remember the way the soldiers literally dug in, seized land, made their forts into cantonments, produced their own food. Soldiers married local women. So there are many districts and dialects tracing their distinctiveness back to the time, many centuries ago, when their ancestors arrived as soldiers, and stayed.

The modern, centralised, command and control state rapidly grew well beyond those military compounds. Wherever the redistributive state was able, through coercion, to direct emigrant settlers, including demobilised revolutionary soldiers, to settle the virgin unploughed lands of Xinjiang and Amdo, new compounds grew.[3]

Initially, to the displaced pastoralists, these compounds, the production bases of a Construction Corps or State Farm, were less familiar than the military compounds. Their physical shape was legible, even if the compound was fenced to sharply demarcate the immigrant new reality that was superimposing itself onto the fluid, unfenced older pastoral reality. It was evident that the immigrant Chinese workers every morning left the compound in trucks, to build roads and other basic infrastructure, and returned each evening to the fenced safety of the compound. The fenced, sharply demarcated compound was the urbs, the walled town, in miniature, implanted into the rangelands.

Even if drogpa were fenced out, it was apparent that within the compound the Han had built dormitory housing, canteens, workshops, even factories, and administrative headquarters, with a school and a first aid station. It was a complete, self-enclosed world, the proto city in miniature, as a single enterprise.

What remained mysterious, not at all evident, was the source of this vigorous implantation of compounds. What was driving this new economy? Conquest, even when acutely painful, is comprehensible. Attempts at ploughing and cropping pastoral lands were comprehensible as efforts to live off the land, even though most such experiments failed. So what was driving all this compound based activity? A new kind of economy had arrived, in the wake of a new kind of military power spearheaded by modern artillery. How to make sense of this?

DISCOVERING THE IRON RICE BOWL

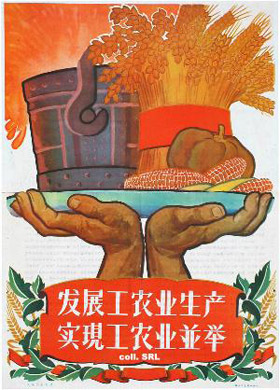

Soon enough Tibetans were themselves inside the compound, rounded up like their animals, in the hasty collectivisation of the Great Leap Forward.[4] It was the great misfortune of Tibet to experience total military defeat in the late 1950s, when Mao’s revolutionary enthusiasm for mobilising all productive forces was at its height, and nomads were rapidly consolidated into production brigades.

Although it took decades for the communes to collapse, the earliest years were especially disastrous. Cadres held greater power over Tibetan lives than feudal rent-seeking land owners had ever had. Tibetans were compulsorily agglomerated into communes, their herds compulsorily aggregated, and herders were granted survival rations only if they earned work points sufficient to have labour translated into flour.

In these ways rural Tibetans discovered the iron rice bowl, the guarantee provided by the revolutionary state that if you are absorbed into a danwei work unit, itself part of a collective or a commune, the distant state will feed you, for life. The unbreakable, life-long iron rice bowl was the primary source of regime legitimacy, especially across lowland China, with recent memories of warlord ruin, civil war, Japanese invasion and famine.

Tibetan pastoralists, used to a life of acute uncertainty out on the range, where anything could happen, were deeply struck by the magic of the iron rice bowl. Even when the worst famine ever known[5] reduced communards to eating bark and grass, and dying, the promise of the iron rice bowl retained allure. The state’s failure to fill those iron rice bowls with food, after three years of starvation, eventually turned out to be temporary, and the magnetic attraction of iron rice bowl security returned.

SMASHING THE IRON RICE BOWL

China’s decisive turn to neoliberalism in the 1980s dramatically changed the concept of the iron rice bowl, which suddenly epitomised all that was inefficient, bloated, overstaffed, unproductive about China. The new slogan, under Deng Xiaoping, was the necessity of smashing the iron rice bowl. Under Deng and later Zhu Rongji, and with external support from the World Bank, payrolls were slashed, guaranteed employment for life was stigmatised. While factory workers were made redundant, the administrative and managerial classes only grew, especially in Tibet, where industrialisation was limited to a few extraction zones, and the maintenance of “stability” became a huge source of employment. The iron rice bowl, especially in Tibet, lived on, even if in public discourse it was no longer the raison d’etre of state legitimacy.

Across China, among the older generation, there remains a nostalgia for the iron rice bowl time, not only because of its secure employment guarantee, but because its stands for a period of shared values and common purpose, in contrast to the hypercompetitive present. But the iron rice bowl is long smashed, except in Tibet, where the surveillance state constitutes as much as 60 per cent of the economy of Tibet Autonomous Region.

INVENTING THE GREEN RICE BOWL

Cities exist because they reach deep into the countryside, making it into a hinterland. Cities extract from the ecosystems and production landscapes of the countryside all of their water supply, food production and clean air to blow away urban pollution. Urbanism is entrenched as the primary mechanism for attaining all of China’s goals of new era prosperity, post-industrial as well as industrial development, poverty alleviation and much more. Yeh and Makley distil this succinctly: “the ideology of urbanism has replaced that of industrialization as the medium of history and progress. Thus, as Oakes put this, ‘The state in China reproduces itself in urbanism, not merely by constructing cities, but in the way the state is restructured and reorganized in the form of urban institutions.’”[6]

The benevolence of the central state remains the hegemonic speaking position, but the state, in its benevolence, now shifts from depicting the lumpen category of herders as the sole cause of ecological degradation, to also being its victims, thus deserving benevolence.

URBAN SECURITY OUT ON THE OPEN RANGE

The new slogan is “one household, one post” 一户一岗 yi hu yi gang, as the mechanism for fulfilling the most labour intensive part of park administration, the data gathering generated by painstaking observations of wildlife in habitat, plus garbage disposal, and property maintenance, none of them jobs likely to attract motivated Han year round.

The state acquires, out on the open range, an ability to scrutinise the privileged green rice bowl few, usually found only in cities, under hitech surveillance. One household, one post fits into old Chinese governance structures of collective responsibility and collective punishment if any family member is deemed guilty of infraction. The loyalty of the entire family is thus guaranteed. Filial piety of the peripheral to the central is thus guaranteed.

By pinning to the state the secure livelihoods of green rice bowl clients of state power, the security state, as patron, ensures the loyalty of entire families, including those who now live in cities. The new national park system, especially the elaborately planned Sanjiangyuan, extends the reach of the urban state into vast areas primarily designated for urban consumption, by mass tourism, on the promise of seeing not only Tibetan antelopes and gazelles but even snow leopards. This is a new form of urbanism, which requires pristine wilderness as the setting that will attract the urban leisure masses, rather than pastoral production landscapes, nowhere near as attractive to urban imaginations.

DO TIBETAN NOMADS HAVE A FUTURE?

But what of the other customary residents of Sanjiangyuan and beyond, their traditional stewardship of landscapes and wildlife, the maintenance of their sacred sites, their secure land tenure rights, their food security?

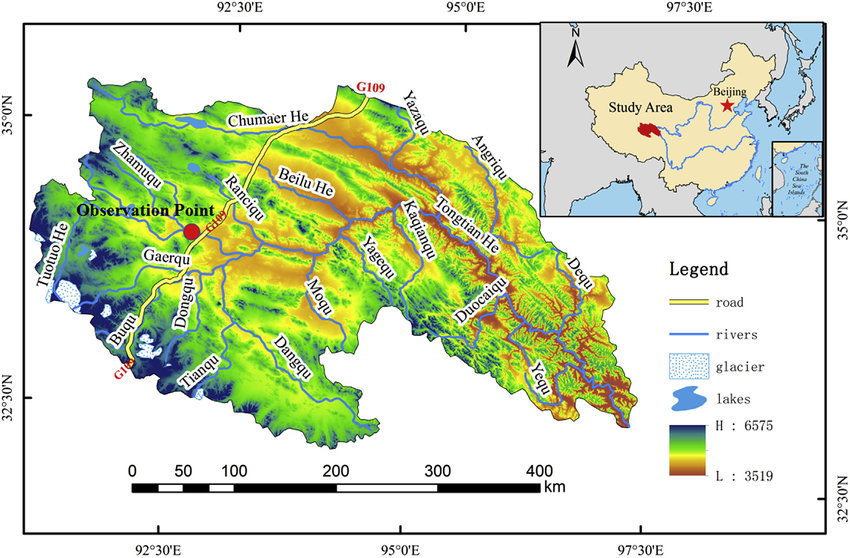

On official statistics, as recently as 2016 Amdo/Qinghai still had 4.8 million yaks and hybrid cattle on the hoof, over 12 million sheep despite a decline in sheep raising in prospering Yartsa gumbu caterpillar fungus collection districts,[8] and 1.8 million goats. This includes nonpastoral and minimally Tibetan areas of eastern Qinghai, where animals are penned and fed on fodder crops.[9] Within the new Sanjiangyuan National Park the yak herd was 900,000 in Golok prefecture and 1.9 million in Yushu prefecture; sheep in Golok 390,00 and in Yushu 530,000, in 2016.

The human population of rural Golok, excluding the prefectural seat, was 168,000 and of rural Yushu 368,000 in 2016.[10] The number of households was 70,000 in Golok (rural and urban) and 110,000 in Yushu. To these can be added the several counties included in Sanjiangyuan, beyond these two prefectures.

What will happen to all those animals, to the pastoral production system on which Tibetan food security and herd genetic diversity depends, and to the many households which will not obtain a “one household, one post” state guaranteed green rice bowl? What will happen to the large number of animals “freed for life” tsethar, free to wander until they die of natural causes, freed by their pastoralist owners, from the prospect of slaughter?[11] If the rangelands are remade into pristine grassland ecosystem wilderness, who will ensure the sentient beasts freed to live out their days are not poached by new arrivals?

Figures on the total size of Sanjiangyuan in official reports vary between 152,000 sq kms and 363,000 sq kms. This is a huge discrepancy . Much remains unclear. While the rural population of Sanjiangyuan is around 600,000 people, overwhelmingly engaged in livestock production on the rangelands –some of the best pasture lands of the entire plateau- what is not clear is the staging of Sanjiangyuan. It seems the scope of the park is planned to widen over the years beyond 2020, and that the 2020 launch is focussed on the defined “core” and “buffer” districts mapped by scientists as crucial for distant lowland water supply and compromised by land degradation.

Also unclear is the pace and extent of displacement of drogpa, as there are other ongoing official policies that continue to promote livestock production, while pushing it to feedlots with Chinese characteristics, intensively fattening livestock on urban fringes, while also continuing to support the traditional Tibetan mode of production on the open range. This is confusing.

Even in a single media story, several policies, pulling in different directions, are listed, as if there is no contradiction. On one hand, the construction of urban fringe intensive high rise housing blocks for former nomads continues to get bigger; on the other hand there are programs to stockpile fodder so that, when a disastrous blizzard happens, emergency fodder supplies can be trucked to remote, snowed-in areas to save the lives of starving animals unable to paw through heavy snow to feed.

There are also plans for a compensation scheme, which is intended to pay modest amounts to drogpa nomads who lose some herd animals to predation by snow leopards, wolves or bears. While this may not be a big expense for government, it is a sign that for some time to come, extensive open rangeland production will continue, and herders will be incentivised to not hunt down wolves, bears or leopards, because compensation will be payable, to avoid human-wildlife conflict, as conservationists call it.

Taken together, this suggests policy incoherence, but the Tibetan Plateau is huge, policy implementation varies a lot in different areas. What is clear is that, in the core 152,000 sq kms of Sanjiangyuan, the mobile mode of extensive pastoral production is officially outmoded, and is to end.

TIBET AS CHINA’S ECOLOGICAL SECURITY BARRIER

The shift in the official Chinese imaginary of the entire Tibetan Plateau, from industrial extraction of raw material producer goods, to a post-industrial leisure and hospitality destination marketed as a pure land of grassland wilderness, is a dramatic transition, with far yet to go.

The origins of this transition, consonant with China’s overall transition from world’s factory to post industrial services-driven economy, go back at least a decade, especially in Tibet Autonomous Region. Perhaps there was a recognition that despite massive infrastructure investment, the sheer size, aridity and cryospheric climate of Tibet meant the dream of wealth accumulation from resource extraction was unlikely to eventuate on anything like the scale Mao envisaged.

Chinese planners see the liminal moment, the dawn of the new era, as 2009: “On the 18th of January 2009, the State Council of China principally approved the proposal submitted by the People’s Government of the Tibetan Autonomous Region of China (TAR), to conserve and build the Tibetan Plateau as an ecoshelter. This is considered one of the most ambitious national environmental protection and restoration programmes in China. It will last twenty years, and over 15.5 billion Yuan (2.4 billion USD) will be invested. According to the final proposal of The National Development and Reform Commission, 2009, the programme was launched because of the significant function the Plateau plays in stabilizing the climatic system, maintaining water resources and hosting rich biodiversity, which was being depleted by increasing grassland degradation, desertification, soil erosion and biodiversity loss. The programme included five conservation projects (rangeland conservation; forest fire and disease control; protection of wild plants and animals and construction of protected areas; wetland protection; and development of alternative rural energy), four restoration projects (forest shelter building, grass planting, rangeland restoration, and desert and soil erosion control), and one monitoring and assessment project. It is an undoubtedly magnificent programme.”[12]

That assessment of China’s pivot, by plateau research scientists in Beijing, Kunming and Lhasa, was published in 2011. Since then this ambitious and magnificent program has gotten bigger and better financed, to now include the four new national parks in Tibet, with Sanjiangyuan the headliner. The ambitious mission has grown to making China an exemplary:

- ecological civilisation,

- a model to be emulated throughout the developing world,

- a global leader in biodiversity conservation,

- water retention and provision,

- carbon sequestration,

- land degradation neutrality,

- payment for environmental services,

- participation in carbon markets, and more.

- Attaining UNESCO World Heritage status for many of the new protected areas is also a high priority.

As the vision of Tibet as ecological safety barrier has progressed, Sanjiangyuan, China’s Number One Water Tower, has come to the fore as the most important of all providers of environmental services from Tibet, and the locus of innovative inscriptions of state power, including the mobilisation of a cohort of Tibet park staff with guaranteed green rice bowl employment.

Yet the resourceful, adaptable land and water frogs of Tibet may amphibiously find ways of being both urban and rural, maintaining identity and curating their ancestral landscapes, leaping from nomadic uncertainty to rice bowl certainty and back again.

To be realistic, the scattered Tibetan drogpa frogs have little chance of evading the predatory crow, if other Tibetans just look on, and do nothing.

It’s not only Chinese cadres who disdain nomads, the experts at living off uncertainty. Secular urban Tibetans also dismiss the pastoralists as backward, as Tsering Bum reminds us. The nomads face the power of the party-state alone, to be removed, family by family, by China’s latest technology of enforcement: the green iron rice bowl police.

[1] Saverio Kratli, Living Off Uncertainty: The Intelligent Animal Production of Dryland Pastoralists, European Journal of Development Research, 2010, Vol. 22, 5, 605–622

Saverio Krätli, Wenjun Li et al, A House Full of Trap Doors: Identifying barriers to resilient drylands in the toolbox of pastoral development; IIED Discussion Paper, 2015

[2] Shan Jie in Golmud, Tibetan villager resettlement program leads to improved ecology in Qinghai, Global Times Published: 2019/April/16 http://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1146161.shtml

[3] Greg Rohlf, Dreams of Oil and Fertile Fields, The Rush to Qinghai in the 1950s, MODERN CHINA, Vol. 29 No. 4, October 2003 455-489

[4] Dhondub Choedon, Life In The Red Flag People’s Commune, 1978

[5] Ian Johnson, Finding the Facts About Mao’s Victims, http://www.nybooks.com/blogs/nyrblog/2010/dec/20/finding-facts-about-maos-victims/

[6] Emily T. Yeh & Charlene Makley (2018): Urbanization, education, and the politics of space on the Tibetan Plateau, Critical Asian Studies, 50, 4, 2018

[7] Herdsmen become the main body of ecological protection of Sanjiangyuan, Qinghai Scitech Weekly 10 April2019 http://www.cnepaper.com/qhkjb/html/2019-04/10/content_1_4.htm

[8] Kabzung/ Ga Errang, The case of the disappearance of Tibetan sheep from the village of Charo in the eastern Tibetan Plateau. Tibetan pastoralists’ decisions, economic calculations, and religious beliefs, Études mongoles et sibériennes, centrasiatiques et tibétaines , 50 | 2019,

[9] Qinghai Statistical Yearbook 2017, table 12-16

[10] Qinghai Statistical Yearbook 2017, table 4-4

[11] Gillian G. Tan, “Life” and “freeing life” (tshe thar) among pastoralists of Kham: intersecting religion and environment , Études mongoles et sibériennes, centrasiatiques et tibétaines [Online], 47 | 2016

[12] Fu Yao, Tu Yan-li , Yang Yong , To build the Tibetan Plateau as Eco-Shelter: from Policymaking to Designation, Action and Reconsideration; in: Pastoralism and Rangeland Management on the Tibetan Plateau in the Context of Climate and Global Change, Hermann Kreutzmann, Yang Yong, Jürgen Richter eds, GIZ German Development Agency, Bonn, 2011