GOING STRATEGIC IN THE BADLANDS

China’s latest railway across Tibet into the Xinjiang desert

China’s railway builders boast they are not only part of the Belt and Road, they are the Belt and Road. They also boast that for a long time they have been listed in the Fortune 500 top companies worldwide and have now made it into the top 50. This state-owned dragonhead of China’s expansion has reason to be so boastful.

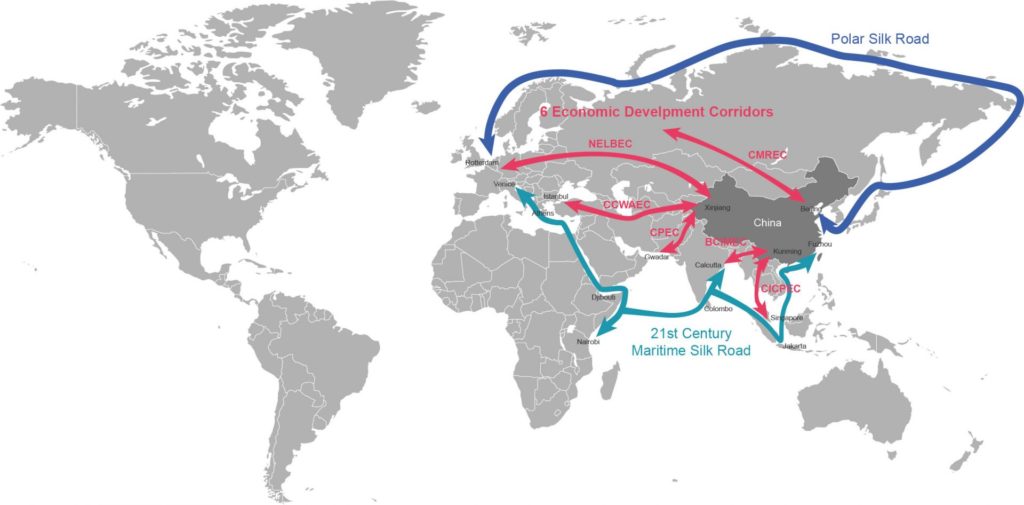

From the outset the Belt was steel track, from western China through central Asia, all the way to Europe, with branches to Pakistan and an Indian Ocean connection with the maritime Road. The engineering of all that track laying, tunnelling and bridging has resulted in CREC, the China Railway Engineering Group, not only cracking the global corporate top 50 but also attracting customers worldwide, especially in Africa and SE Asia.

Thus far, it’s all well known, a regular feature of Chinese media, and of course it’s all win-win.

What is less well known is how busy CREC is in Tibet. Everyone knows about the single track from Lanzhou and Xining to Lhasa via Gormo (Golmud in Chinese), opened to traffic in 2006. There has also been publicity about the rail line under construction from Chengdu to Lhasa which, because of the terrain, is taking several years to build through the rugged landscapes of Kham.

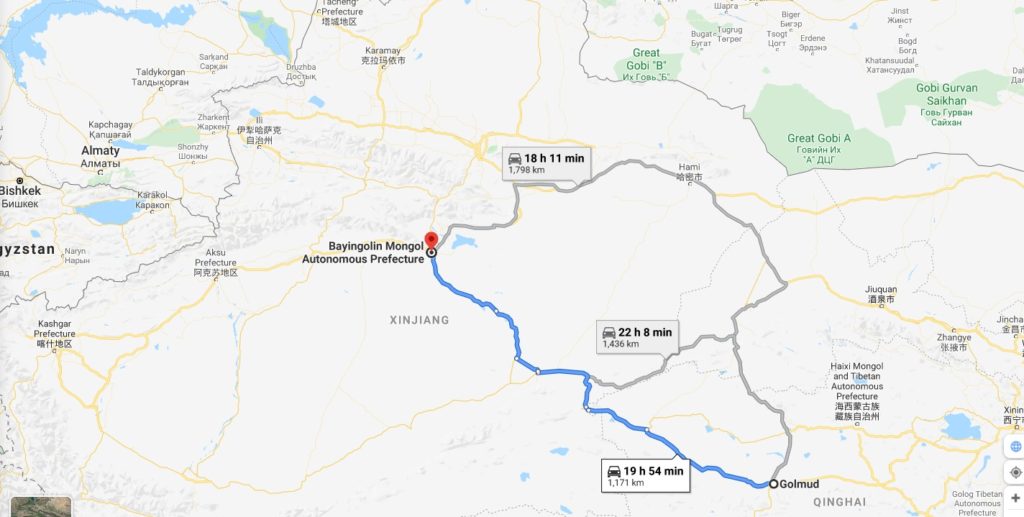

However, CREC is also busy building two more rail lines across Tibet, that few seem to have heard of. One is from Amdo Tsonub Gormo to Korla in Xinjiang. The other is from Xining to Chengdu.

Both, inevitably, are defined as poverty alleviation, good for the locals, access to markets, win-win.

But, on closer examination these two new rail routes tell us much about China’s motives and plans.

A RAILWAY FROM NOWHERE TO NOWHERE?

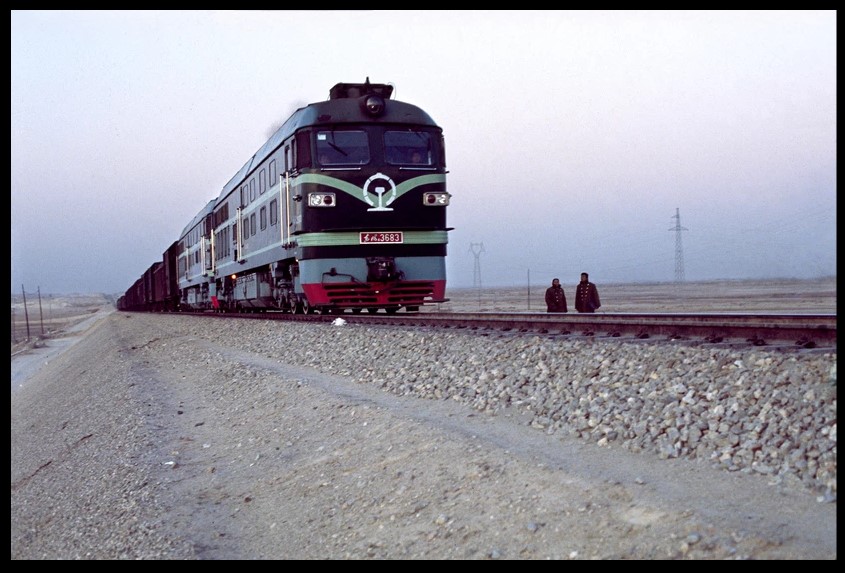

First, the head scratcher: Gormo northwest to Korla. China calls it the Geku rail line. From an engineering perspective, construction is not as challenging as the climb up the Tanglha Riwo into the Chang Tang alpine desert permafrost, to get through to Lhasa. The altitude is lower and can largely skirt the flanks of the Kunlun Mountains which also run in a line southeast to northwest. That’s why this line, through cold, arid and windswept landscapes is coming on fast.

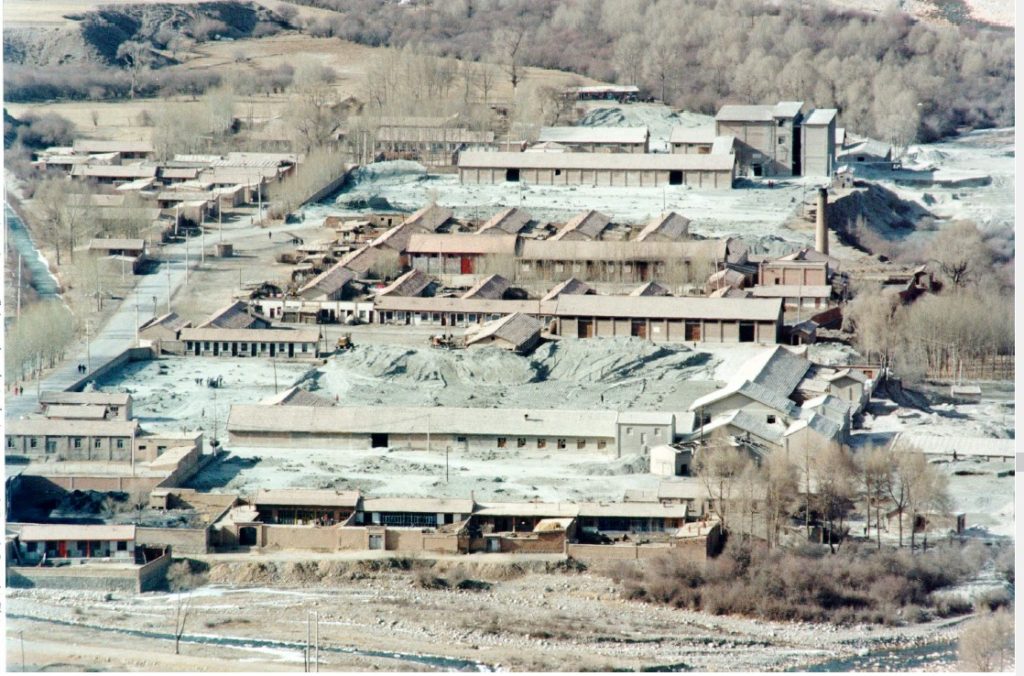

The puzzle is: why? Gormo is by far the most industrialised district of the entire Tibetan Plateau, an enclave of extraction and heavy industrial processing, for export to inland and coastal China, in the opposite direction to Korla. For decades China has extracted oil, gas, potash, magnesium, lithium and common salt from the Tsaidam Basin, in massive amounts. The combination of fossil fuels and metal salts provides all the key ingredients for the manufacture of a wide range of key products, including fertilisers, plastics, explosives, petrochemicals, pharmaceuticals and more recently, lithium batteries for new energy vehicles.

Much of what is extracted from the Tsaidam Basin goes by rail raw or minimally processed to the factory belt surrounding Xining or on to the heavy industries of Lanzhou, or by oil and gas pipelines. Much is processed in Gormo. If socialism with Chinese characteristics manifests as the factories of high modernity, Gormo is the most modern city in Tibet, even if very few Tibetans live in Gormo, apart from the resettled nomads lined up on its outskirts, with little to do. Gormo faces northeast, towards Xining and Lanzhou, towards inland and even coastal China beyond. So why would China build a 1214-kilometre rail line to Xinjiang, and not to Urumqi but to Korla?

We have known since 2008 that this route was on the Ministry of Railways to-do list. But no business case has ever been published.[1]

NOT THE END OF THE LINE

After Urumqi, Korla is the biggest city in Xinjiang, gateway to the southern half of Xinjiang, which remains largely Uighur, largely poor and unhappy. Korla is the centre of Han colonisation of southern Xinjiang. In some ways it is quite similar to Gormo: an outpost of intensive Chinese investment in industrialisation, a magnet for not only Chinese capital but also a Han Chinese workforce settling into a new home on the frontier, in the hope of getting rich, a hope that eludes many. Gormo and Korla are nodes of Han expansion.

But the similarity of Gormo and Korla is not a reason for 1200 kms of rail line, if anything they have little need of each other. The demand for passenger traffic would be close to zero.

So this is a heavy haulage freight line, but what freight?

From Korla it is only 200 kms north to Urumqi, a hub for quickly despatching Xinjiang production east to inland China, both on the old railway built decades ago and on the new high speed line that spears through northern Amdo en route, tunnelling through the Dola Riwo (Qilian Shan in Chinese) to speed up connections and collapse distance. Neither Urumqi nor the northern half of Xinjiang, nor the existing Belt and Road need a rail line via Korla to Gormo. They already have a direct, high speed connection. Much of what Xinjiang sends east is perishable -melons, grapes- and in no need of a detour to get to market.

IS THERE A BUSINESS CASE?

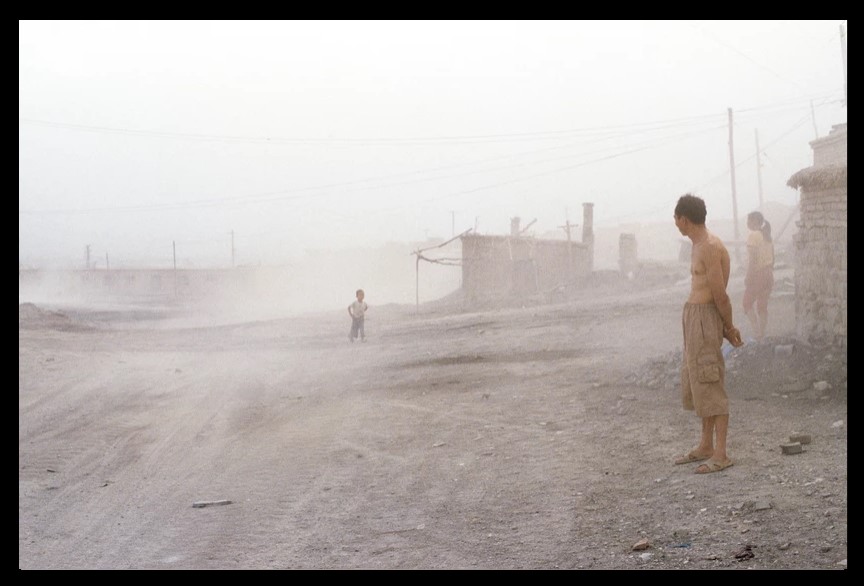

So what has prompted central leaders? Almost the entire 1200 kms route is desert, with very few inhabitants, so agriculture has no part to play. Not even the large scale State farms of the militarised Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps have much interest in these driest of drylands, so remote China in the 1960s used the Lop Nur desert to explode its nuclear weapons tests, to display mushroom clouds to the world, signalling it had achieved nuclear parity with the superpowers.

There is the Mangnai asbestos mine on the Tibet Amdo side, which has operated for decades, despite the great danger to human lungs of breathing in any asbestos fibres. It is hardly big enough to warrant a railroad. The mystery deepens.

On the Xinjiang side, the only town en route is Çakilik, in Chinese卡克里克 Qiǎkèlǐkè but officially known as Ruoqiang, a small town along the chain of old oases linking the Uighur trade towns of southern Xinjiang, again hardly a reason to build a railway. Actually, Çakilik/Ruoqiang turns out, geostrategically, to matter more than Korla.

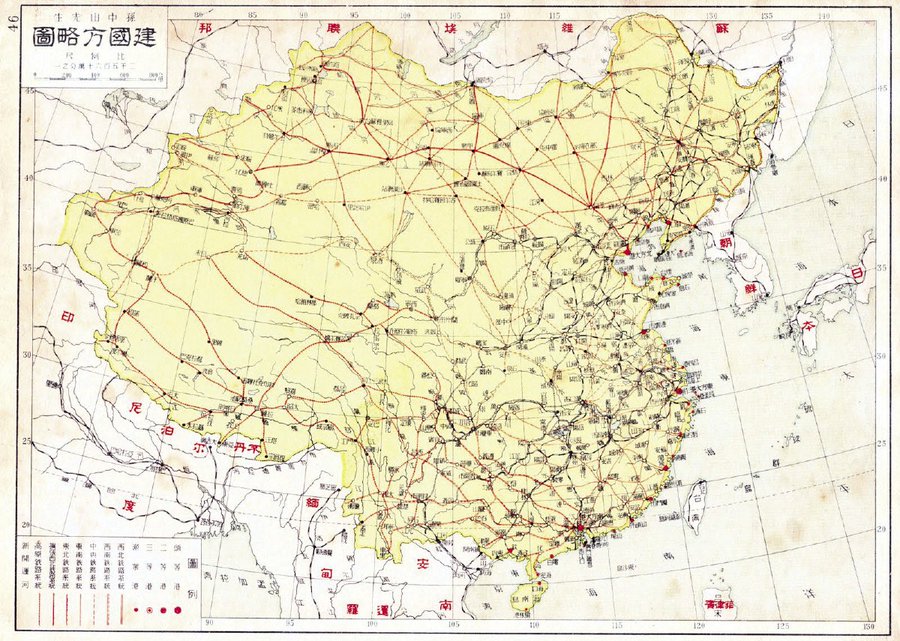

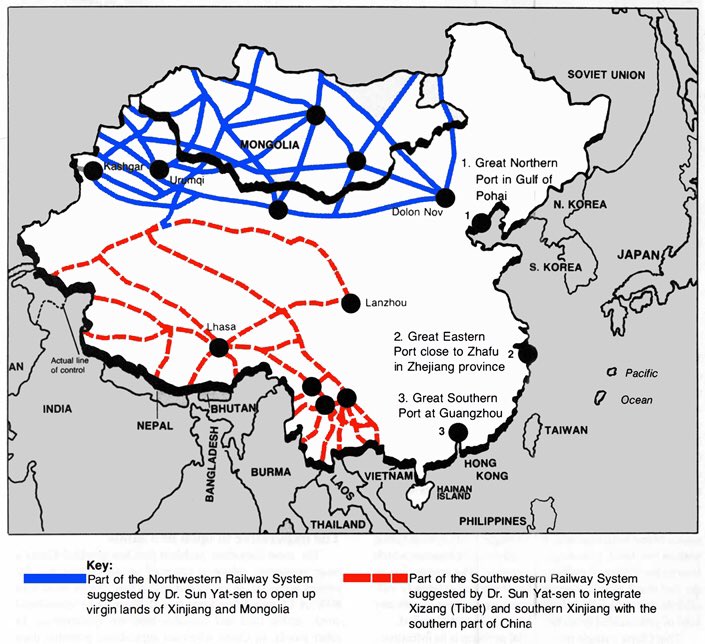

To find an answer to this riddle, we need to start elsewhere. We need to go back a century, to the “father of the nation” Sun Yat-sen, hero of the toppling of the Qing Dynasty. In 1919 he published his vision of a future China which succeeded in integrating its vast land empire into a nation, binding all into one, by railways. In 1919 the steel way (chaglam in Tibetan) was the obvious technology for knitting China together.

Sun Yat-sen’s vision was bold, crisscrossing all of China in a dense rail network that also included Mongolia, since China had not in 1919 yielded Mongolia to the Soviet sphere. Sun’s nation-building weave of tracks was colour coded blue for the northwest and red for the southwest, and where the two colours meet is Korla.

It took a century, but Sun Yat-sen’s vision is at last being built. Trade publication Railway Gazette International explains: “The strategic north-south line connects the long straggling route running west from Urumqi to Kashi with the 1 956 km Xining – Golmud – Lhasa route serving Tibet. It is being developed as part of China Railway’s strategic programme of rail expansion in the west of the country, which includes an ambitious plan to build a complete rail ring around the Taklaman desert in Xinjiang autonomous region.” Key word: strategic.

PROJECTING CHINA’S POWER WESTWARD

If the ring of steel around the huge Taklamakan desert is built, China will achieve a much shorter route to its many international frontiers. Clockwise: Ladakh under direct control from Delhi; Gilgit-Baltistan, the northernmost part of Pakistan; Afghanistan; Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, all abutting southern Xinjiang, which has been so remote, so tenuously linked to China that the oasis towns were until recently intact communities deeply linked to central Asian trade, with the only railway to Urumqi and inland China taking a very long “straggling” route to terminate in Kashgar. Now these six international borders are all strategically important, as Belt and Road corridors of growth and resource extraction, or as recurring security threats, the Gormo to Korla line at last reveals its primary use, as the shortest route from inland China to the frontline. Wherever China looks, in its farthest west, it sees urgent securitisation tasks, whether in the 2020 Galwan and Panggong confrontations with Indian troops, or in securitising the old oasis towns of southern Xinjiang such as Kashgar.

This tilts the Tibetan Plateau, which historically has seldom been a route to anywhere, into a different geography, intrinsic to both the militarisation of the Xinjiang repression and the border confrontations with India. Tibetan scholars have wondered for years whether Tibet is part of the Belt and Road, without finding much evidence that Tibet is included. Now Tibet is a necessary part of the long haul of power projection, the shortest route to the frontier and beyond. Tibet is being geopoliticised, as never before.

China’s long term goal is to be able to access its vulnerable Mid-Eastern sources of oil long before they are shipped by tanker all the way across the Indian Ocean, narrow strait chokepoints in SE Asia, then across the contested South China Sea to ports on the coast. Three quarters of this shipping route could be eliminated if China could bring its crude oil ashore in Pakistan, then take it north to Xinjiang, to the old oasis town of Kashgar, the current rail terminus. The Chinese financed, Chinese constructed CPEC China Pakistan Economic Corridor currently taking shape, will achieve energy security for China, a high priority. The rail line from Amdo Gormo into the deserts of Xinjiang are part of this long-term capability, which could bring tanker wagon trains laden with Mid-eastern oil, to be refined in Gormo. That is still several years away. The CPEC corridor is a highway, starting i8n the south at the Pakistani port of Gwadar on the Arabian Sea, reaching north all the way to Kashgar, an old trading town now bulldozed to make way for a Eurasian logistics hub, while incarcerating the Uighur population in indoctrination prisons. In the longer term the highway is to be paralleled by a railway for bulk transport of goods like oil.

ANOTHER NOTCH IN THE EURASIA BELT?

Kashgar (Kashi in Chinese) has been the terminus of China’s rail system for two decades. While a rail line on from Kashgar, traversing Pakistan south to the ocean may be for the future, the other direction for rail is to head west from Kashgar, traversing Kyrgyzstan and into Uzbekistan, both well endowed with minerals. This is the long-planned CKU (China-Kyrgyz-Uzbek) railway, which has the potential to head much further west, all the way to Europe, further collapsing distance, as it would be as much as 1000 kms shorter than the current Eurasian transboundary interconnection at Xinjiang Khorgos, far to the north. So the Gormo to Korla line is just part of the jigsaw of further shortening the distance between China and Europe.

When China completed its long railway line to Kashgar in 1999 there was much talk of the push westward across Kyrgyzstan and beyond, but it has not happened. Kyrgyzstan’s terrain is so rugged the Soviet rail network barely entered during the decades when Kyrgyzstan was the outer margin of the Soviet Union. Kyrgyzstan does not have the capital to build the railway itself and is more interested in linking the north and south of the country than in a west-east transit corridor for Eurasian silk road BRI traffic. A 2019 Asian Development Bank report tried to rekindle enthusiasm: “Especially important for the Kyrgyz Republic among the PRC proposals to strengthen and diversify Landbridge rail links is a Kashi–Osh–Andijan rail link, which would provide the missing link in a potentially major PRC–Iran– European Union rail line. The PRC’s 1,446-km South Xinjiang Railway from Turfan to Kashi was completed in December 1999, and in the early 2000s the PRC proposed extending the railway with a Kashi–Andijan line, linking to Uzbekistan’s rail network. The PRC–Kyrgyz Republic–Uzbekistan railroad would traverse and tunnel from the PRC’s far western rail terminus at Kashi to the Kyrgyz–Uzbek border town and trade hub at Kara-Suu, 20 km north of Osh, and would then connect with the Fergana Valley’s rail network, which links the region’s major cities and the GM Uzbekistan plant in Andijan. However, the project was dormant between 2005 and 2010. The PRC–Kyrgyz Republic–Uzbekistan railway network could be integrated into the PRC’s BRI via connections to ports in Pakistan, Iran, and Turkey.”[2]

KORLA: DRAGONHEAD OF HANIFYING XINJIANG

These strategic objectives require Gormo to be linked westwards to Çakilik/Ruoqiang. So why does this new rail line continue beyond Çakilik/Ruoqiang, further north to Korla?

Xinjiang is huge, bigger by area than Iran. For several decades China has long focussed on northern Xinjiang, where the oil, gas, coal, minerals and Eurasian interconnections all clustered, neglecting southern Xinjiang as offering little more than poor Uighurs, deserts and nuclear testing sites. Korla was the one outpost of Hanification in southern Xinjiang, the base of two regiments of the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (XPCC/bingtuan).

The XPCC for decades adopted the historic strategy for colonising conquered lands, a labour-intensive settlement of poor Han peasants seeking a better life in new lands, guarded by garrisons of troops, who were also customers for whatever crops could be grown. In the 1950s, human labour “reclaimed the wasteland”, and a substantial Han working class struggled, under XPCC command, to make the drylands yield more. Korla was their hub for the projection of Han hegemony over southern Xinjiang.

Now there is a substantial Han population in Korla who feel they, their parents and perhaps grandparents made Xinjiang theirs, by sweat and hard work, and the “Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region” is outdated. They were the pioneers of land “reclamation”, the builders of productivity. Now they feel they belong in Xinjiang, and Xinjiang belongs to them as much as anyone. This pattern repeats the Han settlement as China expanded south and then inland to the west, o9ver many centuries.

However this underclass has an underclass of Uighurs who have long felt excluded from the benefits of modernity, as James Millward told us in 2014: “Xinjiang’s rapid development in recent years has brought many more Han to the region, and relations between native Uyghurs and these millions of newcomers have grown more and more strained. While standards of living for some Uyghurs have indeed risen in cities, there is a broad perception that Uyghurs enjoy less access to economic opportunities than Han. Many anecdotes, some backed up by documentary evidence, tell of active discrimination against Uyghurs in hiring not only by Han-run private enterprises but by state organs, specifically the massive Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (the Bingtuan), which operates many agricultural, industrial, and commercial enterprises and has listed “Han ethnicity” as a requirement in its job advertisements. Uyghur unemployment runs high despite the booming Xinjiang economy, which is flush with oil money and state investment.”

Tom Cliff, an ethnographer who did his fieldwork in Korla tells us: “Conditions on bingtuan farms have always lagged behind those of urban areas where most of the rest of the Han population in Xinjiang reside. Every bingtuan person I know told me that they and their friends aspired above all else to leave the bingtuan. Historically, then, bingtuan people are the quintessential subaltern constructors. A significant proportion of Han in Xinjiang became frontier constructors by default or by state decree, not by their own design. Many of the voluntary Han settlers of the Mao era sought freedom—from poverty, famine, family, or restrictive social conditions—not nation- or empire-building through territorial gain or the expansion of Han cultural space.”[3]

Today, workers divided against each other on racial grounds is common worldwide. Now the best employment prospects for Han settlers is as guards staffing the prisons and concentration camps, coercing Uighurs undergoing predictive policing re-education for their wrong attitudes. Han-Uighur relations have collapsed.

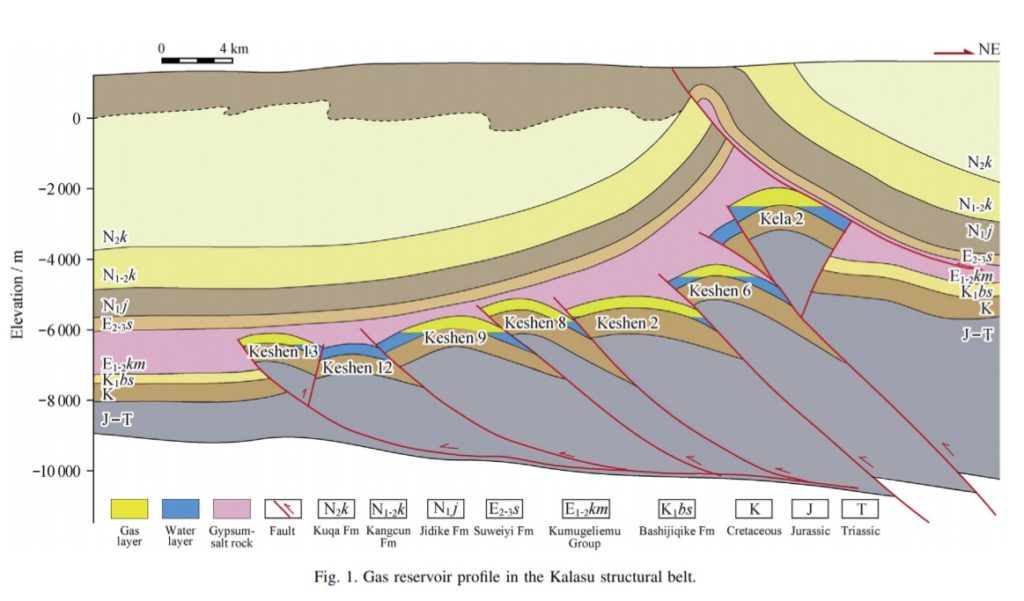

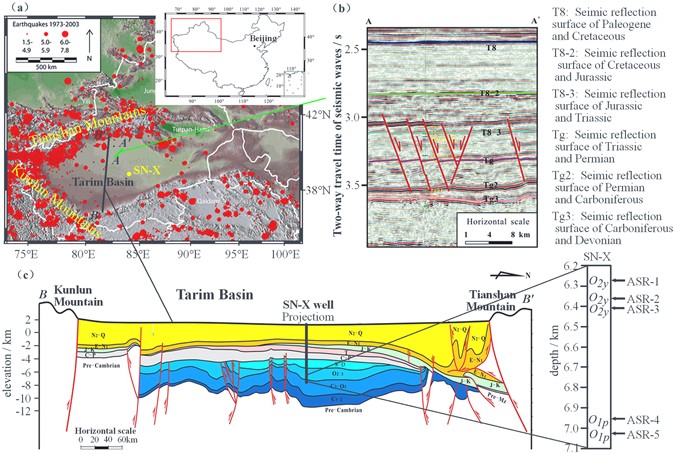

Despite substantial domestic oil output, China is increasingly dependent on Mid East oil, with attendant anxieties about shipping lane security vulnerabilities. Korla is the dragonhead, as they say in China, for projecting the power of the party-state into southern Xinjiang, both to establish Han dominance, and because China discovered oil in southern Xinjiang, several decades after extraction began in northern Xinjiang. Now the Tarim Oilfield Company headquarters dominates the Korla skyline. By 2019 the Tarim oilfields had cumulatively yielded 350 million tons of oil for China, one of the very few domestic oilfields not exploited until the 1990s. As drilling goes deeper and deeper, down to 8ms below the surface, more oil is found.

At great depth, gas is also found, so deep it is also dangerously hot, as much as 180 degrees C. The rock formations in which gas and oil are found are tightly packed, interrupted by fault lines, trapping the gas between gypsum below and water above. How to extract gas from two to seven kilometres below the surface? The answer is fracking, deliberately damaging the rock formations to deliver the gas. How to achieve this? For years China experimented, and many attempts failed. Pumping in water laced with chemicals is no solution in a desert with no available water. The answer seems to be “oil-based fluids.”[4]

Putting oil in to get gas out? Does that make sense?

A NEW NINE DASH RAIL LINE INTO INNER ASIA?

China has projected its power far out to sea, making the South China Sea its sphere of influence, by dredging the reefs and building artificial islands for positioning attack weaponry. This is what China calls the road of the Belt and Road, a maritime road. Now a new rail line is becoming a notch in China’s overland Belt. Arguably China’s Belt and Road Initiative has had little to do with Tibet until now; as ever the Tibetan Plateau has remained too cold and too high, too logistically difficult, easier to skirt around.

The new rail line from Gormo to Korla, at first glance from nowhere much to nowhere much, turns out to be strategic, part of a much bigger geopolitics game of shrinking Eurasia, overcoming the tyranny of distance, delivering raw materials to China. In this process Amdo Tsonub becomes just another geography, territory to be traversed, conquered, reduced, nullified as an impediment to wealth accumulation, just a link in a commodity chain stretching across Eurasia. Tibetans have never thought of themselves as steppingstones to Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan or Pakistan. This is new.

If Tibet has been effectively downgraded, as just one geography among many in Inner Asia, Tibet is reduced to a single attribute: extent. That existent extent is conquered by the speed of the new railway, no longer a barrier to China’s power projection far, far to the west. Tibet is now measured by China’s railway engineering capacity to master extent, reducing even this last attribute to absence. Dryland Tibet then becomes a void, its last attribute absent, nullified by rail.

However Tibet as a geography for production, consumption, tourism and high-speed traverse, is quite a different story, the topic for another blog, focussing on another new but very different railway under construction, from Xining to Chengdu. Departing this platform soon.

[1] US Congressional-Executive Commission on China, Special Topic Paper: Tibet 2008-2009, 47, https://www.cecc.gov/sites/chinacommission.house.gov/files/CECC%20Special%20Topic%20Paper%20-%20Tibet%202008%20-%202009%20-%2010.22.09.pdf

[2] Takashi Yamano, Hal Hill, Edimon Ginting, and Jindra Samson, Kyrgyz Republic: Improving Growth Potential, Asian Development Bank, 2019, 193-4 https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/527161/kyrgyz-republic-growth-potential.pdf

[3] Tom Cliff, Refugees, Conscripts, and Constructors: Developmental Narratives and Subaltern Han in Xinjiang, China, Modern China 2020

[4] Du J; Liu Q; Guo P; Jiang T; Xiong Y; Jiang X, Study on Water Displacing Gas Relative Permeability Curves in Fractured Tight Sandstone Reservoirs Under High Pressure and High Temperature, ACS omega [ACS Omega], ISSN: 2470-1343, 2020 Mar 27; Vol. 5 (13), pp. 7456-7461; Publisher: American Chemical Society

Zhao, Jinzhou; Pu, Xuan; Li, Yongming; He, Xianjie, A semi-analytical mathematical model for predicting well performance of a multistage hydraulically fractured horizontal well in naturally fractured tight sandstone gas reservoir, Journal of Natural Gas Science and Engineering. May 2016 32:273-291

Jiang, Tongwen; Sun, Xiongwei, Development of Keshen ultra-deep and ultra-high-pressure gas reservoirs in the Kuqa foreland basin, Tarim Basin: Understanding and technical countermeasures, Natural Gas Industry B. January 2019 6(1):16-24

Zhu, Jinzhi; You, Lijun; Li, Jiaxue; Kang, Yili; Zhang, Junjie; Zhang, Dujie; Huang, Chao, Damage evaluation on oil-based drill-in fluids for ultra-deep fractured tight sandstone gas reservoirs, Natural Gas Industry B. July 2017 4(4):249-255

Ma, Hongyu; Gao, Shusheng; Ye, Liyou; Liu, Huaxun; Xiong, Wei; Shi, Jianglong; Wang, Lin; Wu, Kang; Qi, Qingshan; Zhang, Chunqiu. Change of water saturation in tight sandstone gas reservoirs near wellbores, Natural Gas Industry B. December 2018 5(6):589-597