SUSTAINABLE WILDLIFE, SUSTAINABLE TIBETAN LIVELIHOODS

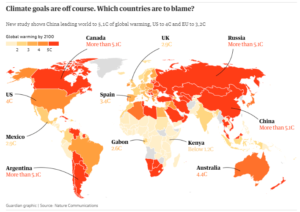

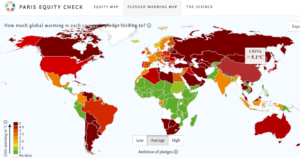

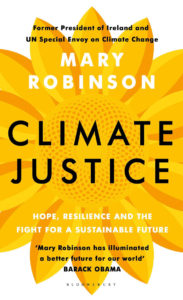

“The industrial powerhouse China and major energy exporters are doing almost nothing to limit carbon dioxide emissions.” That is how The Guardian sums up China’s inaction on climate change, summarising a 2018 report in a leading scientific journal warning against the likelihood of global warming spiralling out of control. The journal, Nature Communications, warns that the global consequences of China’s pledges made to the 2015 global climate treaty negotiations will result in global heating of the climate, by the end of this century, by more than five degrees C. The UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) says any temperature rise greater than 1.5 degrees will be disastrous. China’s vague emissions pledges are alarming.

China, however, has answers to its critics. China has backers who hope against hope China will be the good guy, even a world leader in saving the planet, in the absence of America.  Above all, China has Tibet. By declaring huge portions of the Tibetan Plateau as national parks, available for investment as carbon trading targets for China’s fleet of coal-fired power stations, China plans to get credit for making Tibet all that China is not: a pristine wilderness of depopulated grassland dedicated to carbon capture, water provision to lowland China, and biodiversity conservation of iconic species.

Above all, China has Tibet. By declaring huge portions of the Tibetan Plateau as national parks, available for investment as carbon trading targets for China’s fleet of coal-fired power stations, China plans to get credit for making Tibet all that China is not: a pristine wilderness of depopulated grassland dedicated to carbon capture, water provision to lowland China, and biodiversity conservation of iconic species.

The four new national parks across Tibet will be formally launched in 2020, plus a further six (much smaller) national parks in lowland China. Then there’s the Kailash Sacred Landscape, inching its way forward to inscription as a UNESCO World Heritage landscape.

China’s national parks system is taking shape. As details emerge, this Rukor blog will track the available evidence, and present it for your judgement. Already one crucial aspect is apparent, that makes all the difference to how this promising prospect looks through Tibetan eyes. The emptying of rural Tibet of most of the Tibetan population, into crowded concrete settlements on urban fringes, is essential to this national parks plan, as the Key Ecological Function Zone system draws its’ exclusionary red lines around Tibetan landscapes.

Exclusion, exclosure, clearance, depopulation, displacement are terms used around the world for the displacement of populations, in the name of development, by states and rich landowners determined to dictate the fates of local communities, from the Scottish Highlands to the Amazon rainforests of Brazil, to the productive pastoral landscapes of the Tibetan Plateau.

Growing more grass, to capture more carbon is essential to the design of this new national parks system in Tibet. Without the exclusion of grazing there would be a steady state of biomass, seasonally maintaining the long term equilibrium of grass growth and grazing pressure, that has kept the pasture lands of Tibet sustainable for thousands of years.

That is no longer what China wants. Top priority now for China is enhanced water delivery from Tibet, boosted by glacier melt and geoengineered cloud seeding; and enhanced carbon capture available for electric power generator investment in carbon emissions offsets. That is what matters now to China’s central planners. The nomads have to exit the scene.

Much of this vision for the future role of Tibet, and the lack of role for the Tibetans, is new, and will surprise many who assume China’s motives have not changed much. Yet China has changed direction, and is now gradually repurposing Tibet. Much is yet to emerge; carbon trading is still in its infancy. This blog charts the emerging trend.

Evidence of that shift is the task of this Rukor blog. Over successive blogs, Rukor will dig deep into the available evidence, so you can make your own assessment. Since 2011, in close to 200 blogposts www.rukor.org has tried to offer Tibetan audiences advance notice of what China has planned for Tibet.

China is always planning something, and those plans keep changing, as China shifts to its’ “new era.” Those plans have many consequences in Tibet, for local communities impacted by mines, hydro dams and high speed rail lines. But the impacts are sometimes more widespread, affecting the whole viability of the customary Tibetan livelihoods and values.

Sometimes China’s plans fail to materialise, even when included in successive Five-Year Plans, intrinsic to the official agenda of top-down development. The “pillar industries” promised by those Five-Year Plans largely flopped.

So Rukor’s task is to alert readers to what seems to be ahead, and also to assess the practicalities, and likelihood those plans, often grand plans, have of actually being implemented. That makes for lengthy blogs, looking at China’s plans from several angles, including Tibetans in remote valleys designated for a cascade of hydro dams, and also the competing Chinese interests that may, for example, oppose diverting water from the Yangtze to the Yellow River, because they live on the Yangtze and rely on it.

The stories Rukor tells are often complex, a mix of geology, geography, economics, politics and culture, plus the engineering of Tibetan landscapes. Not an easy read.

HERE WE GO AGAIN

China’s system of national parks is due to be officially launched in 2020, giving us time to think through what this will mean for Tibet. As this news spreads, perhaps the initial, cheerful Tibetan reaction will be to welcome these new parks, obviously a whole lot better than mining and exploitation.

But nationalising vast Tibetan landscapes, repurposing them as mass domestic tourism destinations, has many consequences to consider.

The key conclusion is that China’s plans lock traditional Tibetan land users –the drogpa nomads- out of the parks; even though this is unnecessary, as drogpa have lived sustainably alongside wild herds of antelopes and gazelles for thousands of years, and know intimately how to care for the grasslands.

The new parks mean the end of the traditional Tibetan mode of production, an end to Tibetan land tenure security and collective food security; replacing productive and sustainable landscape management with idle lives on urban fringes dependent on rations handed out by authorities who expect gratitude in return.

This is a familiar process, of exclusion, enclosure, clearance of pastoralists classified as poor, ignorant and to blame for pasture degradation actually caused by past policy failures. So in many ways, this is a familiar story, ever since in 2003 China launched its official slogan, tuimu huancao, close pastures to grow more grass. Human rights monitors have reported on this displacement and depopulation, usually prompting little response. China has argued that such removals of both herds and herders is a scientific necessity, because the visible degradation of grazing land is due to the ignorance and primitive mentality of herders who don’t care about consequences. That racist depiction of drogpa as uncivilised despoilers of a commons they don’t own and don’t care about, has been critiqued by much on-the-ground research, both by international and Chinese scientists, as Rukor has reported. But China sticks to its official narrative that degradation is the fault or f backward herders, not a consequence of policy blunders which may not be mentioned as that is impermissible “historical nihilism.”

Gradually, the argument for depopulating the Tibetan grasslands has morphed into a much wider rationale. For official China, this is not only about degradation, it is above all about guaranteeing water supply from Tibet to lowland northern China. It is also about displacing communities in the name of poverty alleviation, on the official assumption that Tibetan landscapes are inherently and inevitably so unproductive that poverty is inevitable, unless people are compulsorily moved.

All of these official arguments –degradation, water and poverty- made nomad removals a scientific, objective necessity. Now, in addition to those three arguments, comes a new one, that wildlife protection requires all human activities (except science and tourism) to be excluded, in order to save iconic wildlife. Traditional mobile pastoralism is now classified as just as bad as mining and deforestation, requiring new legal status for the new national parks, new land zoning, new management and strict limits on human use of landscapes especially in designated “core” areas of these vast parks.

Four official discourses now come together –degradation, water supply, poverty and wildlife protection- to depopulate rural Tibet, especially the best pastures of Amdo, including the entire prefectures of Golok and Yushu.

Relying on these four arguments, and on official “red line” zoning, Tibetans will be more excluded than ever, from their own lands, although some will be allowed to remain, at least for a while, in the designated “buffer” and “experimental” zones within the national parks but outside the “core”. Some drogpa will be trained and employed as national park rangers, to welcome visitors, pose for tourist photos, and to enforce the ban on herds and herders. Overall, this signals the end of lifeways that made Tibet humanly habitable, and speeds up the accelerating urbanisation of Tibet.

From a human rights perspective, herding herders on to concrete accommodation, on urban fringes, into allotments so small there is no room for animals, violates not only individual civil and political rights but also collective social and economic rights to livelihood and land security.

Much of this has been covered before, but until now the removal of drogpa has been piecemeal, and not rigidly enforced. Sometimes herders have been able to rent their animals to other drogpa who remain on their land, and return occasionally to look after land and animals. Implementation of tuimu huancao has been patchy and slow, coinciding in many areas of eastern Tibet with the boom (and later bust) of the yartsa gumbu caterpillar fungus market, which lessened reliance on sheep and yaks for livelihood.

Now the pace of depopulation is accelerating, with fewer exceptions. Now China has the added acclaim that readily comes with the concept of the national park.  Now China is adding yet another argument to the four already invoked to justify the cancellation of land tenure rights and the displacement of so many drogpa. The emerging fifth argument is global climate change, with a Tibetan Plateau free of grazers and grazing becoming a carbon sink, capturing carbon in grass growth, to save the planet and restore China’s green credentials, especially the reputation of China’s coal-fired power stations, which will be able to pay nominal amounts to offset their smokestack emissions, in China’s new carbon trading scheme. Capturing carbon in grass requires contracts guaranteeing no grazing for the rest of this century, penalising not only the present generation of drogpa, but generations to come. Read the fine print.

Now China is adding yet another argument to the four already invoked to justify the cancellation of land tenure rights and the displacement of so many drogpa. The emerging fifth argument is global climate change, with a Tibetan Plateau free of grazers and grazing becoming a carbon sink, capturing carbon in grass growth, to save the planet and restore China’s green credentials, especially the reputation of China’s coal-fired power stations, which will be able to pay nominal amounts to offset their smokestack emissions, in China’s new carbon trading scheme. Capturing carbon in grass requires contracts guaranteeing no grazing for the rest of this century, penalising not only the present generation of drogpa, but generations to come. Read the fine print.

So now, in official eyes, there are five compelling reasons why, as part of China’s great rejuvenation, mobile pastoralism is the past. All five can claim scientific justification, with lots of narrowly defined research findings in support. Above all, the world is likely to receive the 2020 launch of the new national park system across the Tibetan plateau as a self-evident good news story.

Who could possibly be against conservation, especially when it protects iconic species such as Tibetan antelopes?

Who could possibly be against conservation, especially when it protects iconic species such as Tibetan antelopes?

In China’s official version, it comes down to a dualistic choice: you can have antelopes, water supply and carbon capture, or you can have nomads wandering the landscape aimlessly and destructively, you can’t have both. A lot of conservationists worldwide will buy that, readily believing that all human presence in protected landscapes is dangerous. China expects to be widely congratulated when it launches its national park system in 2020, and probably will be.

If Tibetans find that outcome unnecessary and problematic, it will be up to Tibetans to tell the more complex story of nomad displacements and exclusions, and why that dualistic either/or logic is mistaken.

Why monitor China’s plans for Tibet, in advance? All too often, in Tibet, the first Tibetans know that a mine, a big hydro dam, a high speed railway is to be built nearby is when the construction crews and heavy equipment arrive. Tibetan communities do protest, but too often it is too late, and the party-state stands behind the miners and dam builders, ready to criminalise all protest, and break up petitioners violently. All too often removals of nomads are done without the wider world knowing.

To know is to prepare, to gauge how to respond, to mobilise support, let the world know it’s not as simple as “national parks, hooray.” There once was a time when Tibetan voices were listened to round the world, but that is decades gone. These days it takes at least a year to mobilise sufficiently for Tibetan concerns to be heard. It took the Uighurs a year of monitoring and documenting mass disappearances, construction of huge indoctrination camps, before the world started to listen. If Tibetans decide the closure of Tibetan livelihoods, the cancellation of rural Tibetan life, is worth protesting, and worth proposing constructive alternatives, there is just enough time to mobilise.

The emptying of pastoral Tibet is a human rights story, a development story, an environment story. That means the opportunity to connect with many audiences, in many countries. If we learn how to tell this story, we will perhaps also be challenging some habitual assumptions made by rights monitors, by development advocates and environmental campaigners. So we cannot expect immediate sympathy. We will find China has made skilful use of the standard concepts and categories of rights, development and environment, to make the nationalisation of Tibetan lands, on a huge scale, seem logical and necessary. China has been putting its case for years, with little Tibetan input.

On balance, we could decide it is all too hard, that the depopulation of rural Tibet and intensive urbanisation are already a done deal. Or we could carefully assess the detailed evidence assembled in these forthcoming blogs, note that there are well placed allies within China, and work on bringing together the rights, development and environment folks, into a new coalition that finds an effective voice.

If a campaign grows, it cannot expect quick results. Many conservationists will agree with China that it is best to keep humans out of protected areas, and that Tibetans must be strictly controlled to prevent hunting, and clashes over wild yaks attacking well-bred and well-behaved domestic yaks. The world’s biggest environmental NGOs, long embedded in China, will be the last to listen. Development advocates may say China’s rural land is controlled by local collectives, and if those locals decide, for the sake of building the nation, that they must become ecological migrants, we should not interfere. They may say that all over the world governments infringe on the lands and rights of indigenous minorities, so Tibet just joins the long queue. Rights advocates may say their hands are full holding China accountable over transgressions of individual civil and political rights, and this is a question of economic and social rights, too hard to get traction. Enclosures mean Tibetan drogpa may be losing their land tenure security, and Tibet as a whole losing its food security, but those are not headline issues.

China’s planned system of national parks is taking years to design and launch, for a reason. China is taking time to mobilise a welcoming chorus, with high profile friends such as the US National Parks Service. Above all, the national park is a brand that is recognised, appreciated and believed in worldwide, a self-evident good that needs little justification. Any Tibetan mobilisation begins with a recognition that the wind is not blowing our way.

China’s planned system of national parks is taking years to design and launch, for a reason. China is taking time to mobilise a welcoming chorus, with high profile friends such as the US National Parks Service. Above all, the national park is a brand that is recognised, appreciated and believed in worldwide, a self-evident good that needs little justification. Any Tibetan mobilisation begins with a recognition that the wind is not blowing our way.

If Tibetans around the world do decide that Tibetans in Tibet should not be protesting alone and unheard, this issue has the potential to knit together new audiences, reach new publics, amplify Tibetan concerns, get Tibet back on the agenda.

If Tibetans do find their voice on the emptying of Tibet, it will be taken up by environmentalists and development folks worldwide. What they will discover, as Tibetans speak up, is that concepts familiar to them become strange when “Chinese characteristics” are added. Natural capital valuation, carbon trading, community based development, biodiversity conservation, climate change mitigation, community conservation, ecological migration, poverty alleviation, provision of environmental services, net land degradation neutrality, reducing emissions from deforestation and degradation, land reclamation are concepts which are usually meant to be empowering of local communities, but in Tibet, in practice, disempower. This may be news to both environmentalists and developmentalists.

There may be initial disagreement, as China has been arguing its case for excluding nomads for years, in professional conferences. Yet a distinctive Tibetan voice will be heard, and reset a new normal. The world has learned that China’s ways of doing globalisation, reciprocity, fair trade, technology transfer, cyber security, access to information, definitions of human rights and much else are not what the rest of the world thought they meant.

There may be initial disagreement, as China has been arguing its case for excluding nomads for years, in professional conferences. Yet a distinctive Tibetan voice will be heard, and reset a new normal. The world has learned that China’s ways of doing globalisation, reciprocity, fair trade, technology transfer, cyber security, access to information, definitions of human rights and much else are not what the rest of the world thought they meant.

Now the world can discover that that China’s master plan to lock Tibet, not just now but in coming generations too, into “red line” ecological zones is actually because the whole of lowland China is so urbanised, overcrowded, overstressed, in need of vacationing in unspoiled serene wilderness. Tibet is being made into China’s ultimate Other, China’s orientalist fantasy “no-man’s land” of pristine, unpopulated wilderness, to compensate for China’s urban density.

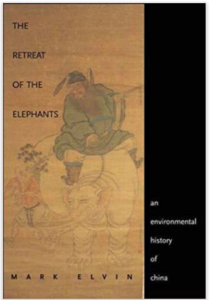

A thousand years ago elephants roamed freely across China; two hundred years ago half of China was panda habitat. The elephants are gone, and the remaining pandas survive in the hilly Tibetan borderlands, soon to be upgraded to national park status, which means excluding the locals. Tibet is to pay for China’s concentrations of wealth, power, consumption and wasteful use of natural resources. Tibet is to be all that China is not, a virgin land untouched by human hand, other than the benevolent reach of the state.

This is a dramatic story, of the shift in official thinking towards Tibet, from extraction and exploitation to orientalist consumption destination. That shift is far from complete, only now beginning to gain momentum. There is still time for constructive alternatives, that include Tibetan pastoralists as part of the solution, not just as those to blame for problems. If Tibetans speak up, voicing the concerns of Tibetans inside Tibet now being dispossessed of their land tenure rights in the name of water provision, high speed tourist railway construction, national parks and wildlife conservation, the world will hear.

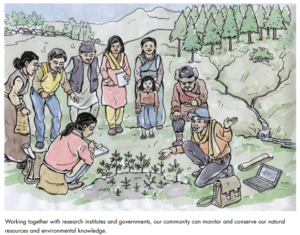

The world already has a roadmap, and detailed directions as to how to get there, that would include not exclude rural Tibetans, to achieve environmentally sustainable development. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), adopted by all countries, including China, bring together both environment and development, climate justice, traditional land management knowledge and much more. Implementing the SDGs in Tibet would enable a genuine win/win, conserving biodiversity, protecting landscapes and empowering local communities. This is not a situation of having to ask the world to drop its preconceptions and start anew. The map for an empowered, sustainable Tibet exists.

The SDGs are a new generation of human rights, which all countries, China included, have pledged to implement, with a target date of 2030. Packed into the 17 SDGs are many more explicit commitments to human rights: “explicitly grounded in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights treaties, and affirms that the 17 SDGs seek to realise the human rights of all. Further, the pledge to leave no one behind reflects the fundamental human rights principles of non-discrimination and equality. Human rights are reflected throughout the SDGs and targets. Concretely, 156 of the 169 targets have substantial linkages to human rights and labour standards. The SDGs and human rights are thereby tied together in a mutually reinforcing way.”[1]

The preamble that begins the SDGs proclaims: “The 17 Sustainable Development Goals and 169 targets . . . seek to realize the human rights of all and to achieve gender equality and the empowerment of all women and girls. They are integrated and indivisible and balance the three dimensions of sustainable development: the economic, social and environmental.” The introduction to the declaration states, “We resolve, between now and 2030, to end poverty and hunger everywhere; to combat inequalities within and among countries; to build peaceful, just and inclusive societies; to protect human rights and promote gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls; and to ensure the lasting protection of the planet and its natural resources.”

The World Bank Legal Review in 2016 published a volume called Financing and Implementing the Post-2015 Development Agenda: The Role of Law and Justice System, on how the SDGs can be implemented and enforced.

The UN Secretary-General made clear that human rights are inherent to the SDGs by condensing the 17 SDGs to six goals: “1. Dignity: to end poverty and to fight inequalities (Goals 1 and 10) 2. Prosperity: to grow a strong, inclusive, and transformative economy (Goals 7, 8, 9, and 12) 3. Justice: to promote safe and peaceful societies, and strong institutions (Goal 16) 4. Partnership: to catalyse global solidarity for sustainable development (Goal 17) 5. Planet: to protect our ecosystems for all societies and for our children (Goals 2, 11, 13, 14, and 15) 6. People: to ensure healthy lives, knowledge, and the inclusion of women and children (Goals 3, 4, 5, and 6).”[2]

The SDGs are more comprehensive than the Millennium Development Goals, which ended in 2015, when the SDGs took over, with much higher standards, and a more comprehensive approach. Negotiating the SDGs was a massive effort involving the entire global communities of environment and development actvists, advocates, think tankers, researchers, governments and UN agencies, in an effort to name specific goals that bring environment and development together, that demand action from governments, and push states to lift their game.

There are several advantages to pressing China to fulfil its SDG obligations in Tibet. Not only did the world’s environmentalists and developmentalists sign on to this new agreement on human rights, after years of negotiation, so too did China, with enthusiasm. China now proclaims its global investments and loans around the world, as part of its Belt & Road Initiative, fulfil the SDGs. China proclaims itself a leader of the developing world, fully embracing the SDGs.

China seeks a reputation for exemplary delivery of SDGs, all over China, and in other countries it invests in. China cannot afford the embarrassment of breaching the SDGs by disempowering, dispossessing and displacing rural Tibet.

If Tibetan voices are absent, China will, yet again, argue that its marginalisation and immiserisation of Tibetans is actually a contribution towards fulfilling sustainability. SDGs with Chinese characteristics will selectively ignore SDG 10 requiring reduced inequalities and SDG 16: “to significantly reduce all forms of violence, and work with governments and communities to find lasting solutions to conflict and insecurity. Strengthening the rule of law and promoting human rights is key to this process, as is reducing the flow of illicit arms and strengthening the participation of developing countries in the institutions of global governance.”

Instead, Chinese appropriation of the SDGs focuses on a narrowly technical interpretation of SDG 15: Life on Land, to protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, arguing that exclusion of nomads from pastures corrects land degradation, and exclusion of farmers from sloping drylands is necessary to restoring forests.[3]

Could China be held accountable for its failures to implement SDGs during the Universal Periodic Review process all members of the UN Human Rights Council must be tested on? Writing in the Bulletin of the World Health Organisation, several human rights lawyers argue just that.[4]

That is the sort of intersection of human rights and environment that recharges the debate and gives the Tibet question fresh traction. Environmental organisations are keen to hear from Tibetans. A recent example is the NGO focussed on cloud seeding and geoengineering, which discovered China’s plans to artificially increase rain over Yushu and Golok prefectures of Amdo, to feed more water to downstream China through the Yellow and Yangtze rivers. After being briefed by Tibetans, the ETC NGO came out with a strongly pro-Tibetan report.

POWER OF THE ENVIRONMENT MOVEMENT

If environment advocates understand the threat to Tibetan lives when the exclusionary national parks go ahead as planned, does that mean they are capable of effective action? Consider this, as a measure of the power of environment groups. On 29 October 2018, China’s State Council issued a decree reminding everyone that China remains opposed to trafficking in rhino horns and tiger bones. However, in the fine print, if read carefully, the State Council actually permitted trade and use of both rhino and tiger parts, for “scientific research” purposes, especially for use in Traditional Chinese Medicine, since medicine with Chinese characteristics proclaims both rhino and tiger parts to be virility restorers. The State Council stressed that the source would be farmed animals, kept caged for the sole purpose of harvesting their organs.

Quickly the word spread, reminding us all that once exceptions to a rule are announced, very illegal trade tries to slip in under the guise of the new rule, opening the gate to more slaughter, corruption and trafficking. By 12 November, less than two weeks after media reported the alarm, China quietly gave in, and reversed its window for TCM sales and “scientific research” on rhinos and tigers, both farmed and wild.

It may have taken the Uighur of Xinjiang a year before the world looked more closely at Xinjiang, but it took little more than a week before China’s party-state, at the highest level, decided that yielding to TCM lobbying, in the name of “Chinese characteristics” was actually bad reputationally.

Whether we like it or not, there are many more people motivated to protest for animal rights than human rights. The environment movement is powerful globally, and in China. Let national parks onto the agenda.

[1] Birgitte Feiring et al, Building a pluralistic ecosystem of data to leave no one behind: A human rights perspective on monitoring the Sustainable Development Goals, Statistical Journal of the IAOS 33 (2017) 919–942

[2] United Nations, The Road to Dignity by 2030: Ending Poverty, Transforming All Lives and Protecting the Planet, Synthesis Report of the Secretary-General on the Post-2015 Agenda, 2014

[3] Xiufeng Sun . Lei Gao . Hai Ren et al, China’s progress towards sustainable land development and ecological civilization, Landscape Ecology, (2018) 33:1647–1653

[4] Judith Bueno de Mesquita, et al, Monitoring the sustainable development goals through human rights accountability reviews, Bulletin of World Health Organisation, 2108;96:627–633