WORLD’S BIGGEST HYDROPOWER MEGA DAM?

For thousands of years fabulists, fantasists, visionaries have felt attracted to Tibet as the locus of their fabulations. From the giant gold digging ants of Herodotus, robotically delivering buried gold for human consumption, through to Madame Blavatsky, Nicholas Roerich, Nazi SS-Untersturmfuhrer Ernst Schäfer, and Lobsang Rampa, who could resist the allure of a vast, unknown, unknowable island in the sky, where anything could, and does happen?

This essay is not about them, but a more modern generation of visionaries, from the 1950s on; captivated by canyons and wild rivers. Two clusters of visionaries, who did actually gaze into this remotest of remote Tibetan landscapes, in the Great Bend of the Yarlung Tsangpo Canyon, deep in the Tibetan subtropics.

A HEROIC REVOLUTIONARY YOUNG GENERATION

One group is the geologists and hydro dam designers of China, designated heroic shock troops of socialist construction, who superimposed onto the wildest of mountain rivers their concepts of extractable kilowatt hours of dammable, turbine-driven electricity. Plays were written and staged to celebrate their heroic achievements for the revolution, such as Black Stone黑色的石头 by Yang Limn.[1] The playwrights were inspired by PRC President Liu Shaoqi declaring: “Geological workers are the guerillas for the period of peaceful construction.”[2]

The most famous revolutionary play was The Young Generation, by Chen Yun, which can be read in full in English, in the 2010 Columbia Anthology of Modern Chinese Drama.[3]

So we now know how visionary heroes talk among themselves:

“Xiao Jiye: Place: wherever the motherland most needs me. Goal: revolution. I have only one request: give me the hardest work. Try and get to go to our place in Qinghai. Out there where we are, not only is everything under the ground a treasure, but so is everything above the ground. You like shrimp, right? At the foot of the Kunlun Mountains, I’ve seen a lake that’s filled with shrimp. You just reach into the water, and you get a huge handful of them. If you go out there, I guarantee that you’ll have plenty to eat.

Yao Xiangming: Not me. If they could let me choose for myself, I’d still have the same idea of going to Tibet. I’m going to stand on the peaks of the Himalayas and look out over the whole world!

Xiao Jiye: I came back on business for Mineral Region 205.

Xia Gianru: Have you finished writing the detailed investigative report?

Xiao Jiye: Yes, we’ve finished it.

Yao Xiangming: What about the research design? Did you finish that, too?

Xiao Jiye: Yeah, that too.

Zhou Jie: And the conclusion is . . .

Xiao Jiye: There’s ore.

Zhou Jie and Yao Xiangming (together): It’s . . . that ore!

Xiao Jiye: That’s right!’ According to our estimate, the deposit is very large. The quality is very high, too! (Everyone is happy and singing.)

Xia Gianru: And that foreign expert still says that there isn’t any ore there! (Everyone laughs.)

Zhou Jie: If there really is ore, you’ll have made quite a contribution! It’ll make us Chinese all feel proud, and let people see that we do have that kind of ore, and quite a lot of it, too

Yao Xiangming: Ah, you’ve been working so hard! No wonder you’re all tanned! I daresay it was because you were labouring so selflessly.

Zhou Jie: No matter where the party sends me, I’ll pack my bags and go. Of course, at the start there’ll be a lot of difficulties, and perhaps it’ll be very hard. But recently Party Secretary He put it quite well: “The people of this generation weren’t born to take it easy. If there weren’t any difficulties, then what use to have us?”

Xiao Jiye: That’s right. And there were difficulties blocking our progress as members of the prospecting team. For those of us who had lived a long time in the city, it took a while to get used to life in the wilderness; but when we overcame the difficulties, we felt an incomparable joy. On the way back this time I looked in on Mineral Region 508. Three years ago our class went there for practical training. Originally that place was just a vast, uninhabited wild plain, and now it’s already become a modem industrial city.

Yao Xiangming: Geologists are the guerrillas of this period of construction. That says it all: hardship, but glory!

Xiao Jiye: Yes! Some people only know about the hard side of our lives as a prospecting team, but actually, even in the hardest times, we’re still happy. Because we didn’t hold back our strength, we were able to live up to the party’s and the people’s expectations for us. The wind and the snow of the Kunlun Mountains know whether we are cowards or heroes. The fierce sun of the Gobi Desert understands whether we are mud or pure gold. It was just this kind of pride in the team members that brought us inexhaustible happiness and strength, because we were fighting for the happiness of hundreds of millions of people.”

Today, 60 years on. these visionaries define their realm as “tunnelling and underground space technology”, and have a journal of that name for themselves. These days China’s thrust into outer space attracts more attention, but underground space tunnels are essential to China’s plans to lock Tibet into China. These visionaries of red plenty, hydro abundance, work to make scrutable, legible, extractable, commodifiable and transmissible their concept of a new technocrat ruling class, in command of a new asset class, backed by natural capital valuation fictions, that could abstract from this wild river what socialist construction sought. They had no realisation they were actually making up a story, then persuaded themselves it was objectively true.

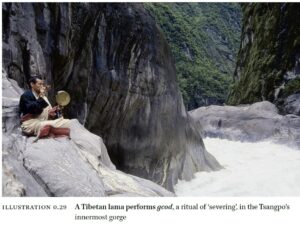

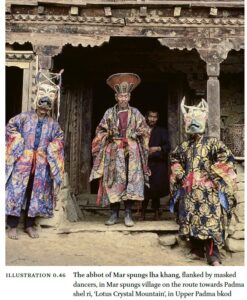

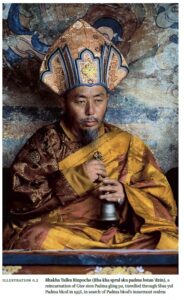

The other group is Tibetan, visionary revealers of treasures that liberate the human mind from all habits and fantasies by recognising all thoughts, all anticipations and conclusions, all subjects and objects, are fantasies, inventions we make and are then imprisoned by.

There is a deep tradition of Tibetan visionaries who discovered and rediscovered this hidden land of Pemmakȏ, which China has now measured for damming. Rig ’dzin ’Ja’ tshon snying po (1585–1656), Rig ’dzin Bdud ’dul rdo rje (1615–1672), Stag sham Nus ldan rdo rje (1655–1708), Chos rje gling pa (1682–1720), and Sle lung Bzhad pa’i rdo rje (1697–1740).Rig ’dzin Rdo rje thogs med, (1746–1797), O rgyan ’gro ’dul gling pa (1757–1824) and Gar dbang ’Chi med rdo rje (b. 1763). These visionaries opened and re-opened these beyul hidden lands, to draw pilgrims to walk the trail, and transform their minds.

Their pilgrimage guidebooks to the Great Bend confer liberating, awakening meanings to rock faces, waterfalls, forests; yet at the same time they tell us these are fantasies, as are our daily self-talk, our grudges, regrets, fears and attachments. As without, so within.

The other vision seems so old it comes from an enchanted world that no longer exists, yet it turns out to be surprisingly modern, fir for purpose for these degenerate, distracted times.

This is the vision of the lamas, whose pilgrimage guidebooks open these lands not to objectifying scrutiny but to surrender, encounter, fusion with rockface, forest, waterfall and sky, opening the mind to all as is, to realise the nature of reality, the unbounded, deeply free nature of mind.

These are visionaries who call themselves visionaries, such is their confidence arising from direct experience in wild mountain and river scapes utterly and instantly liberate the human mind from its obsessions, compulsions, distractions, delusions, resentments, blame.

Many of the pilgrimage guides written to encourage ongoing pilgrims were written in another degenerate time, as the conquering People’s Liberation Army hunted lamas, meditators, poets, visionaries seeking to escape through a pure land, as seen through their pure vision. Having plunged into a hidden land, in Pemakȏ, where even the PLA devil says good night, they paused, to drink in this world in a world, mosquitoes and leeches included, to let rockface speak to them, to hold up to them the face of a deep inner liberation that requires no conquest by machinegun or megadam.

Today, in a time of escalating degeneration, we could instantly dismiss these visionaries as quaint relics of a romantic world that barely exists any more; yet the texts, teachings, practices they wrote, inside the Great Bend Syntaxis, now show up in New York and thus globally as the latest, most direct and effective methods for cutting through delusion, distraction, despair. What is old is new again. What is new about modernity’s insistence on conquering nature is starting to look old.

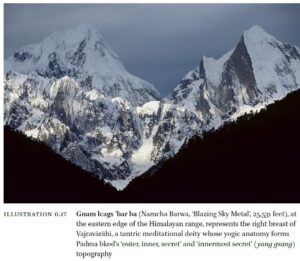

Visions pervade the human gaze, on seeing the Eastern Himalaya Syntaxis. This is where entire continents grow ever upward into the cryosphere and at the same time down, rifting apart, deep into carving the deepest canyon in the world, Simultaneously these lands push north, ever deeper into the Tibetan Plateau, and east into upland western China. The greatest of mountain ranges -the Himalaya-does an abrupt turn, clockwise, an axis driven by molten energies far below, pulling the collision of continents ever deeper into the planet’s core.

In a syntaxis this ongoing axial age simultaneously piles continent upon continent, up into vast sky islands; while at the same time rifting, orthogonally, at right angles, both northward and eastward at once, with deep clefts for the great rivers of Asia wedged between range after range of mountains.

Maybe not surprising these intensely energetic landscapes inspire visionaries. Here a river that has for 2000 kilometres drained the entire north face of the Himalaya abruptly turns south, incising its way right through the Himalaya, falling to India, where the Yarlung Tsangpo becomes the Brahmaputra. These energies are utterly beyond any human scale, yet they inspire visions.

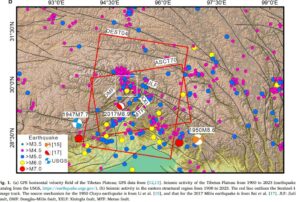

Red lines are faults pushing every which way, blue dots are recorded earthquakes of last 125 years, magnitude above 6; yellow stars are earthquakes above magnitude 8. The difference in shaking , between a magnitude 6 quake and 8.7, the Assam quake of 1950, 500 times as big, The difference in energy, however, is about 11,000 times. Source: Arun Bhadrana, , B.P. Duara , Drishya Girishbai , A.L. Achu, Sandeep Lahon , N.P. Jesiya, V.K. Vijesh, Girish Gopinath, Multi-model seismic susceptibility assessment of the 1950 great Assam earthquake in the Eastern Himalayan front, Geosystems and Geoenvironment, Vol 3, Issue 3, August 2024, 100270

FIRST PASS AT MAPPING

This investigation of the Metok མེ་ཏོག་རྫོང་། / Motuo 墨脱/Metok mega dam enables you to gaze at this very remote landscape through the eyes of central planners, geologists, engineers, local communities, Tibetan treasure revealers and other visionaries, shifting back and forth between perspectives, in the hope of helping you decide how probable is actual dam construction.

However, maybe long form is not what you want, so here -at a risk of spoilers- is a succinct evidence-based summary of key findings, to be explored in depth below.

CONSTRAINTS

Fourteen reasons why the world’s biggest hydro dam, in the world’s deepest gorge, in the remotest Tibetan landscapes is unlikely to ever happen.

1 The state-owned dam builder Huadian, which owns the Yarlung Tsangpo/Brahmaputra river in its 2000 kilometres long traverse of Tibet, shows no interest in attempting to construct a dam on the lower Yarlung Tsangpo, three times the output of Three Gorges. https://rukor.org/chasing-phantoms/

2 An even bigger state-owned dam builder, PowerChina, also shows little interest in a dam which would take at least a decade to build and connect to power grids reaching from far west to the industrial electricity demand in far east. PowerChina now has global reach, many other projects under way that are quicker, easier, less capital intensive.

3 Eastern end of the Himalaya terminates at Namche Barwa, the mountain that must be tunelled so the Yarlung Tsangpo can be diverted into multiple parallel tunnels through one of the most earthquake prone areas on earth

4 The northward thrust of India into Eurasia abruptly changes to an eastward push, which has created the many mountain ranges of Kham, and the deep river valleys dividing them; all at right angles to the main Himalaya thrust. This abrupt clockwise turn, driven from deep within the molten planet, pulls entire continents apart as well as pushing them together. The centre of this syntaxis is exactly where the Yarlung Tsangpo river diversion tunnels and turbines are designed to go. Extremely risky.

5 Catastrophic landslides have occurred frequently on the Yarlung Tsangpo and major tributaries, crashing millions of tons of rock, mud and collapsing glaciers, racing down valleys, ending up far downriver, blocking streamflow that then backs up behind until it bursts through, with disastrous consequences for downriver communities in Tibet and in India. Classic GLOF glacial lake outburst floods, unpredictable and uncontrollable.

6 Tunnelling would be done by massive TBM tunnel boring machines, their vibrations at the rockface set off mini quakes, rock bursts. TBMs are expensive, massive, hard to position them in a rugged mountainscape at the distant bottom end of the tunnel-to-be, to then tunnel up.

7 Most TBMs, whether made in Germany, US and now China are used for railway tunnels, far easier to get in place. China is struggling to deliver the Chengdu to Lhasa railway, huge tunnelling operations experiencing many obstacles, including rock burst, TBM machines jamming, flooding. Very few TBMs currently in use for hydro projects.

8 To generate anything like the mooted power, at least 8 turbines would need to be installed, inside the tunnels, in chambers excavated to accommodate spinning machines each weighing thousands of tons. Existing road access to Metok/Metok མེ་ཏོག་རྫོང་། / Motuo 墨脱, at the mouth of the tunnels, cannot transport these massive machines.

9 Logistically, to get the turbines to the installation site at the bottom end of the water tunnels, it would be far easier to barge the turbines up through the mouth of the Brahmaputra in Bangladesh, up through eastern India; but politically that is impossible. This is not only due to chronic geopolitical tensions but also because the best business case for constructing the mega dam is to then sell the electricity generated to nearby India, since India, despite many plans for big dams not far downriver, has struggled to build them. Not a plausible scenario. India’s deep mistrust of its upper riparian neighbour is primarily due to recent disastrous outburst floods of the Yarlung Tsangpo.

10 The diverted waters of the Yarlung Tsangpo, after four tunnels and eight turbines, would rejoin the river, thus bypassing the Great Bend canyon, and then very shortly enter India. Bypassing the Great Bend, the wildest of wild rivers, also means bypassing the biggest influx of water in the Yarlung Tsangpo watershed, especially in the summer monsoon wet season when major tributaries enhance the streamflow, since summer heat, now intensifying due to climate change, also melts glaciers perched above. If the Metok/Metok མེ་ཏོག་རྫོང་། / Motuo 墨脱 mega dam project misses out on much of the Yarlung Tsangpo’s streamflow, it may not be capable of generating anything like the mooted 60 gigawatts output.

11 All Tibetan rivers including Yarlung Tsangpo reach peak hydropower generating capacity only in monsoon months. In winter, flow is far less, yet distant industrial consumers require reliable 24/7 electricity 365 days a year. Climate change is making monsoons unpredictable, sometimes failing as in 2022, resulting in serious doubt in China as to reliability of big hydro. The 2024 drought again showed increasing unreliability of streamflow.

12 China now prioritises wind and solar power, often in Tibet, often clustered round hydro dams, as faster and cheaper to instal. A mega dam would take at least a decade to construct, probably longer is unforeseen difficulties arise. It would be extremely expensive, tying up investment capital China needs to instead invest in short term quick return consumption stimulus to revive a slowing, stagnant economy. The era of megaprojects seems to be ending, unless it is landing on Mars.

13 China’s central government has struggled for years to direct provincial governments to use electricity exported from Tibet but have failed to prevent widespread “curtailment” and “abandonment” of Tibetan hydro, while provincial bosses prefer their own coal fired power, which they own. China continues to build many more coal fired power plants, often constructed by the same corporations operating in Tibet, including Huadian and PowerChina.

14 A megaproject on this scale, requiring a massive upfront capital expenditure and many years of infrastructure construction before there is any return on equity, requires a powerful patron capable of allocating finance, year after year, sufficient for completion; while China is now focussed on quicker and cheaper tech fixes for ‘green energy”; and is pivoting into “high quality” development, and stimulating consumer spending. There is no sign of any such red gene elite patron, nor any indication of detailed dam project design planning over the past decade or longer.

OROGENOUS, ORTHOGONAL UPLIFTING AND TEARING CONTINENTS APART, ALL AT ONCE

How is it possible these dramatic landscapes are so little known, leaving them to the visionaries?

This is where the biggest inland earthquake ever recorded occurred, the magnitude 8.7 Chayu quake of 1950. Even 75 years later, scientists are still trying to figure out what happened, as molten rock rose so close to the surface, and the quake violently shunted landscapes in several conflicting directions, at once.

Caption: white arrows of Chayu earthquake shoving landscapes in many directions, all at once

A major problem is politics. Three years before the 1950 Chayu quake, the British partitioned their Raj into India, Burma and East Pakistan. The world knows this as the Assam earthquake of 1950. It happened on India’s Independence Day. The explosive energies of the syntaxis and its eastward wrenching of continents embraces all three sovereign states, which seldom cooperate. A 2024 research report funded by China’s National Natural Science Foundation concludes by declaring: “Data availability: The data that has been used is confidential.”[4]

So massive was this 1950 quake, it distorted even the downriver delta of the Meghna/Brahmaputra in East Pakistan, now Bangladesh.[5] Geologists call this a viscoelastic relaxation perturbation.[6] Continental collision flexing its muscles.

Syntaxis interlocks Bangladesh, Assam and eastern Tibet forever. “Two major earthquakes in 1897 and 1950 had a deep impact upon the environment and humans in north-east India. The massive seismic disturbance of 1897 played a crucial role in shaping the physical history of this region. Seismologists have observed that this earthquake holds a ‘prominent place among the great earthquakes of the world’. Another earthquake in 1950 disturbed the region’s physical setting. These earthquakes transformed the landscape of Assam, and, in so doing, affected the lives and livelihoods of human communities. The various geological and hydrological consequences of earthquakes included the creation of floods, landslides, fissures, sand vents and artificial river dams. These changes affected Assamese agriculturalists and fishing communities.”[7]

On this journey we meet the eastern Himalaya syntaxis, where the northward thrust of the Himalayas abruptly ends; the mountain building push of tectonic collision suddenly shifts 90 degrees to push eastward. In a syntaxis, hard to imagine, deep in the semi-molten layer, continental collision pushes mountains ever higher, while at the same time rifting apart, an ongoing double movement not well understood since science has no direct access to the deeply subterranean layers where continents are pulled deep into the depths and abruptly pull apart.

Metok མེ་ཏོག་རྫོང་། / Motuo 墨脱 is at the centre of this syntaxis, not coincidentally. Metok མེ་ཏོག་རྫོང་། / Motuo 墨脱 is at the end of the Great Bend Gorge of the Yarlung Tsangpo river, shortly before the river plunges further into India, becoming the Brahmaputra. The river plunges because the syntaxis plunges on, far past the hard but artificial border, shaping the highlands of eastern India.

So there is a lot more that can be explored, if we are to assess the likelihood of a Great Bend mega dam.

[1] Xiaomei Chen, “Playing in the Dirt”: Plays about geologists and memories of the Cultural Revolution and the Maoist Era, The China Review, vol 5 no.2, 2005, 65-95

Xiaomei Che, Reading the Right Text: An anthology of contemporary Chinese drama, U Hawaii Press 2003

Xiaomei Chen, Acting the Right Part: Political theatre and popular drama, U Hawaii Press, 2002

Joel Andreas, Rise of the Red Engineers: The Cultural Revolution and the origins of China’s new class, Stanford, 2009

[2] Xiaobing Tang, Chinese Modern: The heroic and the quotidian, Duke U Press, 2000, 182

[3] Pages 689 – 691, 2010 edition, not 2014 abridged edition

[4] Weiqiang Li, Evidence for partial melting and earthquake activity in the crust from a 2-D electrical resistivity model in the vicinity of the Chayu region, southeastern Jiali-Chayu fault, Tibetan Plateau, Tectonophysics, Volume 872, 9 February 2024, 230212

[5] Kawser, Umme; Hoque, Abdul; Nath, Biswajit , Observing the impacts of 1950s great Assam earthquake in the tectono-geomorphological deformations at the Young Meghna Estuarine Floodplain of Bangladesh: evidence from Noakhali Coastal Region

Arabian Journal of Geosciences, 2021

[6] Li, Shuiping, Present-day fault kinematic around the eastern Himalayan Syntaxis and probable viscoelastic relaxation perturbation following the 1950 Mw 8.7 Assam earthquake, Journal of Asian Earth Sciences,15 October 2022

[7] Arupjyoti Saikia, Earthquakes and the Environmental Transformation of a Floodplain Landscape: The Brahmaputra Valley and the Earthquakes of 1897 and 1950, Environment and History, 2020, Vol 26, Issue 1Feb