Blog TWO in a series documenting China’s path to urbanising Tibet, depopulating the highlands, converting exnomads into infrastructure construction workers 2/5

AN ARCHIPELAGO OF SECURITISED BORDER VILLAGES

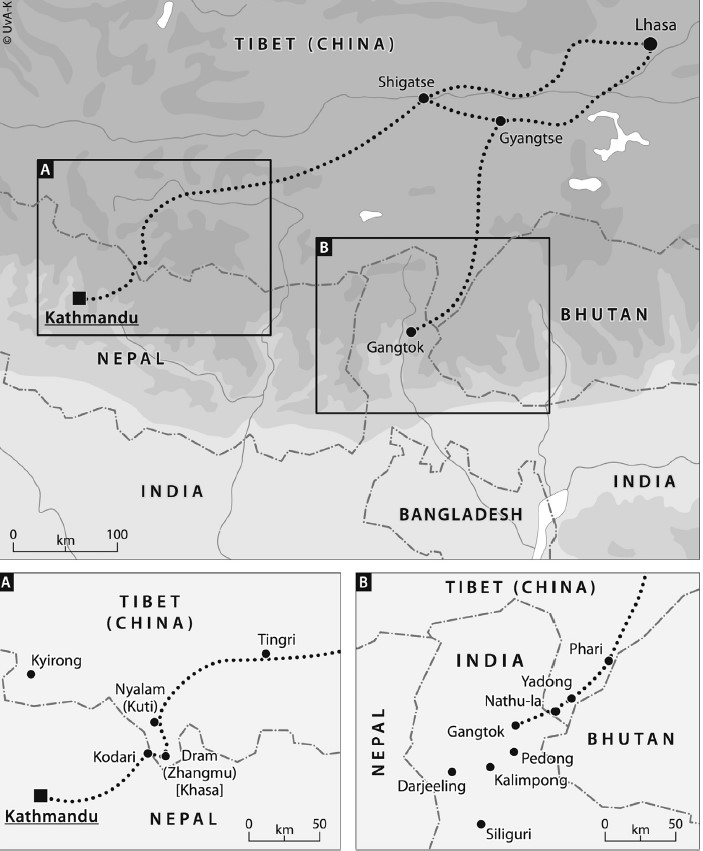

High on China’s construction agenda is the securitisation of over 3000 kms of border, in Shigatse and Lhoka municipalities (formerly prefectures) where Tibet abuts Ladakh, Nepal, Sikkim, Bhutan and Arunachal Pradesh.

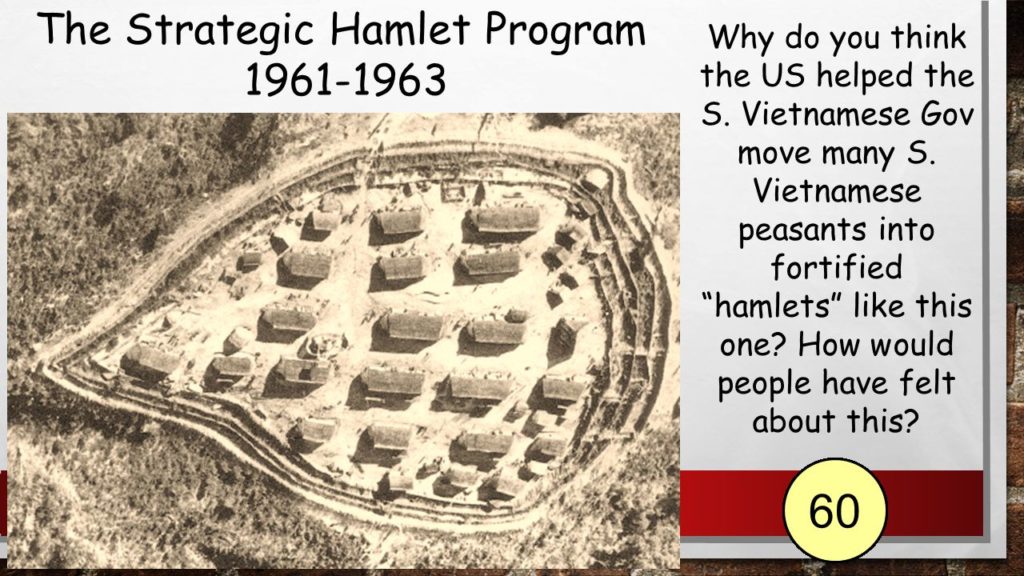

Construction of securitised border villages, in a long chain on the northern flanks of the Himalayas is a high priority, for strategic reasons. This border demarcates sovereign nation-states, and has been a major security concern to China for many decades, so why is China now spending billions on strategic hamlet securitisation? It was across this border the Dalai Lama and tens of thousands of Tibetans, mostly from Tibetan border counties, fled into exile. It was along this border in 1962 that India and China went to war. Until early this century Tibetans finding life under Han racist contempt intolerable continued to find ways through the Himalayas, into exile. This is a border with a long history of militarisation, on both sides.

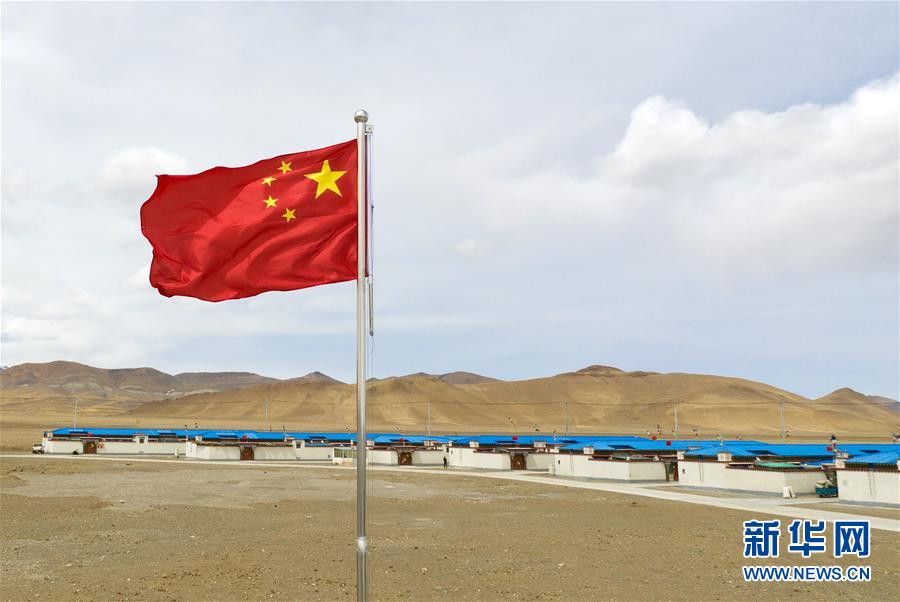

So why, in 2017, did China embark on a major program of border village construction, a program meant to be completed by 2020? Renewed tensions with India mostly occurred later, so that is not the driver. “Plan for the Construction of Well-off Villages in the Border Areas of the Tibet Autonomous Region (2017-2020)” itemises a list of 628 planned new villages all along the border, a remarkable number as the entire chain of 22 border counties is sparsely populated, as it is mostly in rain shadow, the monsoon clouds largely blocked by the Himalayas. With a human population of only 150,000 means each of the 600+ villages on average has only 250 inhabitants, more reminiscent of the strategic hamlets the Americans built in Vietnam.

“Plan for the Construction of Well-off Villages in the Border Areas of the Tibet Autonomous Region (2017-2020)” 西藏自治区边境地区小康村建设规划(2017-2020年)originated in Xi Jinping’s securitisation of everything, by perceptions of risk wherever one looked. The very long Tibetan borders with South Asia, with unreliable, untrustworthy Tibetans on both sides, was an obvious candidate for extending China’s grasp to catch up with its securitising reach, all the way to the Himalayan frontier.

However building all those villages, effectively sedentarising a largely nomadic pastoralist society has in practice eluded China’s grasp. A review of project implementation in April 2019 found that “construction of 330 villages has started, of which 4 villages have been completed.” Why such slow progress?

The plan was to ensure sufficient urban comfort to not only persuade nomads they are better off sedentary, but also sufficiently wealthy to feel loyalty and gratitude towards the party-state. That meant not only concrete housing but urban amenities, including electricity, in a vast land still habituated to hub production of electricity in distant hydro dams, to be extended along high voltage grids to the remote strategic border villages. It turned out to be a logistical nightmare.

The villagisation of southern Tibet failed to meet its target completion date of 2020. The usual industrial operational model of the construction contractors, employing mostly Han workers, just didn’t function in the cold months. The supply lines were too stretched, the scale too small for efficiency, compared to office block and apartment tower construction in cities, or the concentration of labour and resources at a hydro dam site.

In Xi Jinping’s new era, failing to meet targets imperils career prospects of cadres. A new way of getting the border villages built was called for. The new solution, announced in 2020, introduces two new approaches: a greater reliance on assembly line prefabricated building panels, trucked in from afar, and a greater reliance on a Tibetanised workforce, mobilised by displacing Tibetans from their pastoral lands. Neither is entirely new, but they are now scaled up; and interdependent as a Tibetan workforce is needed both for village construction and manufacture of concrete panels and steel frames.

The key announcement was at the Seventh Tibetwork Forum of August 2020, a whole-of-party-state gathering to (re)mobilise the accelerating urbanisation of Tibet. Xi Jinping told the Tibetwork Forum “We must strengthen the construction of border areas and adopt special support policies to help border people improve their production and living conditions and solve their worries.”

A month later, in September 2020, the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference issued a call for compliance with this “primary political task”: “Border areas must resolutely unify their thoughts and actions to the central and district committee’s strategies for rural revitalization and border development. The strategic decision-making deployment of enriching the people has brought together a strong joint force of governing and building Tibet in the border areas of the new era.”

The principal author of this renewed strategy is Tu Deng Kezhu [Drukhang Thubten Khedrup Rinpoche], a member of the National Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference. He named some of the problems: “In order for the “border well-off village” to improve quality and efficiency, it is necessary to transform the resource advantages of the border areas into industrial advantages. The border area is far from the core economic cities, and all aspects of transportation facilities, public services, and industrial development lag behind the core economic cities such as Lhasa and Xigaze [Shigatse]. It is necessary to continue to exert the power of inclusive finance to benefit the people in terms of financing for construction projects in border areas and inclusive financial services for border residents, strengthen financial support in well-off border villages, and open up the “last mile” of financial services.”

The “resource advantages” of border counties can become viable industries only if local enterprises are eligible for access to finance, despite lack of collateral for loan eligibility. Further, those in TAR who do have accumulated wealth that could be invested in remote areas, are much more interested in setting up banking and securities trading subsidiaries outside TAR, because that is where faster money is to be made, as we shall see later in this blog series. The new rich of TAR, the elite managers of the construction companies, look east for wealth management opportunities, not to the border districts. China’s singular reliance on urbanisation as the long term solution for every problem yet again reduces rural, pastoral Tibet to hinterland obscurity.

What are the “resource advantages” of the border counties that could and should, in current plans, become industrialised? Not only are there many mineral deposits thoroughly assessed by Chinese geologists, there are pilgrimage mountains and a climate mild enough in some places to grow walnuts, plums and tea. Then there’s tourism, Chomolangma/Mt Everest the magnet. Above all, there is the massive military presence, which skews local economies towards a wide range of ancillary services.

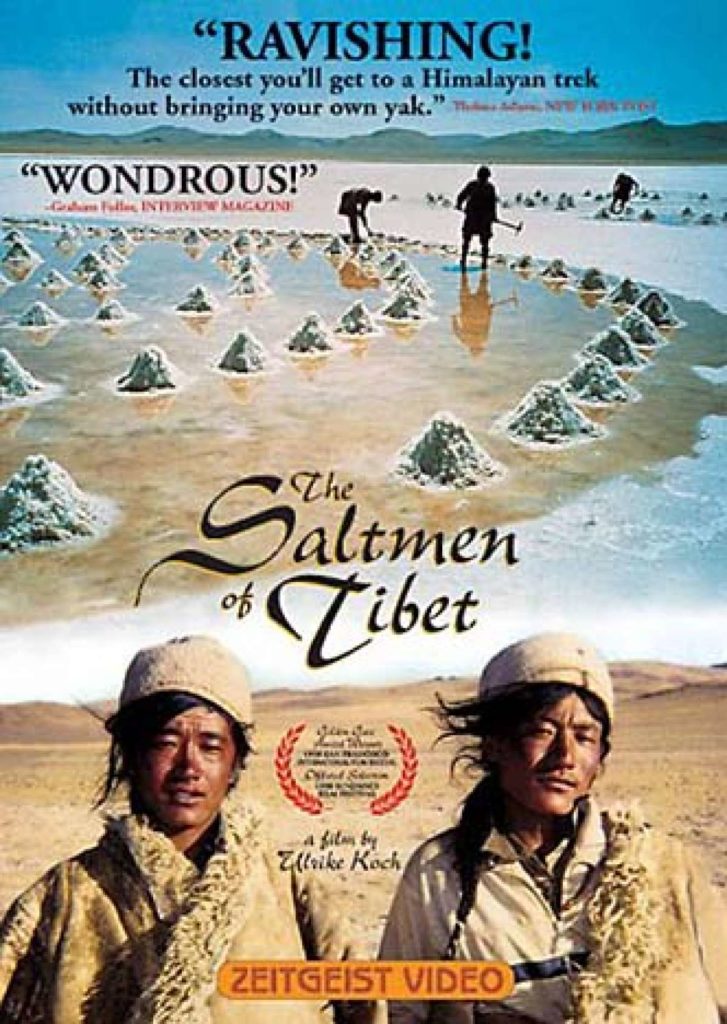

Probably what pastoralists of southern Tibet would most want is for modern nation-states and their hard borders to get out of the way, to resume transHimalayan trading, as their great grandfathers did until 70 years ago. Tibetan traditions of long distance trade caravans would no longer profit, as did the famous saltmen, from herding sheep laden with salt lake bed pristine salt onto pack yak lines surefootedly negotiating the precipitous Himalayan trails, but there is always something worth trading, and Tibetans are good at it.[1] Trading and pilgrimage go together, and there are plenty of sacred places and revered lamas on all sides of the border, awaiting reconnection too.

But the party-state instead intends to extend its grasp, project its power, sedentarise the nomads and turn Tibetans into loyal citizens of distant Beijing. The enduring dream of resuming trading has been named so many times as a goal to be accomplished soon, yet it never eventuates. The CPPCC pays lip service again to trading as the obvious industry for the borders, but it’s all quite vague: “Vigorously develop border trade. Make good use of the border trade policies of the Party Central Committee, the Party Committee and the government of the autonomous region, and vigorously create a development model of “border trade +” or “+ border trade”, relying on the complete logistics system of Lhasa and Xigaze, radiating various border port areas, and realizing through the development path of industrial integration The economic synergy of “border trade +” or “+ border trade” enhances the high-quality development of border trade.”

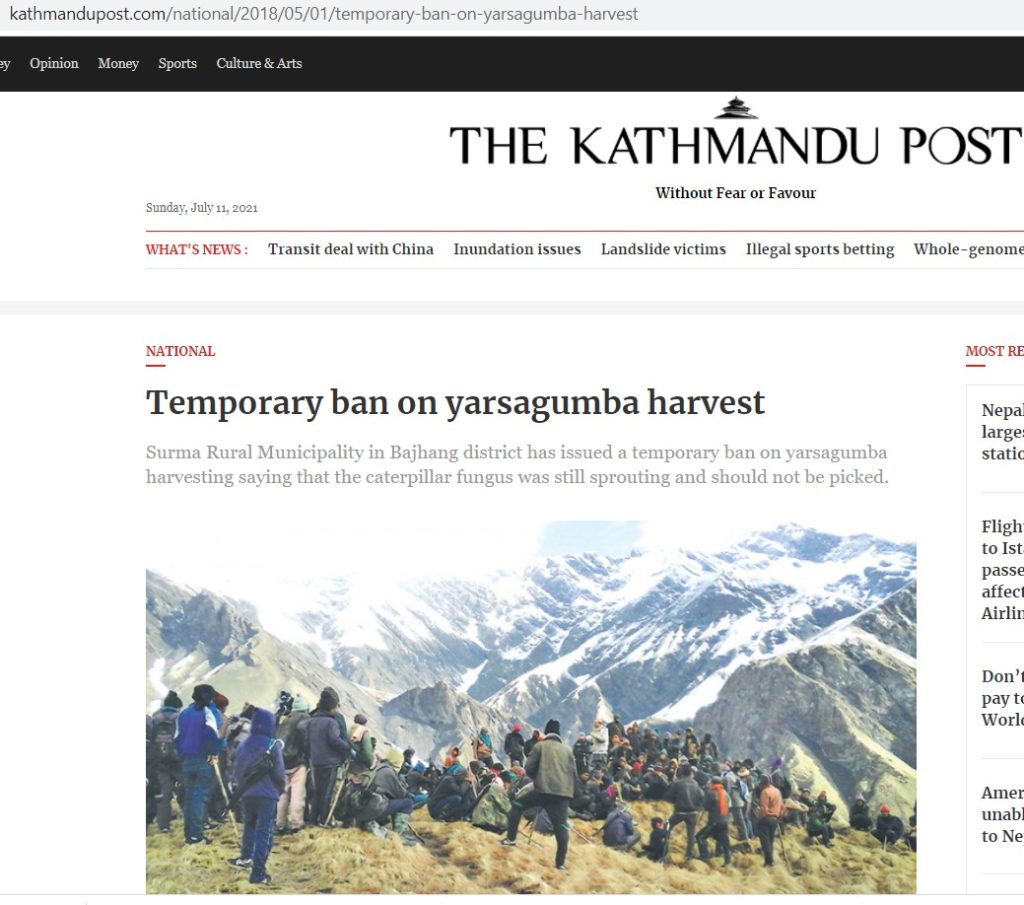

In reality, it will have to be ongoing smuggling, for example the annual spring harvest in upper Nepal of yartsa gumbu cordyceps caterpillar fungus, since the demand is in China, hence the smuggling.[2]

China will struggle to industrialise the border region, and is still struggling with the basics of strategic border village construction, well behind schedule. For central leaders, this is not good enough, in a time when securitisation tops all priorities.

A further motive of China’s ambitious construction agenda for the implantation of model border villages all along the Himalayan borders with India, Nepal and Bhutan, is to showcase China’s reach and urban modernity, exciting envy among these who see these clean lines and speedy construction.

These are often remote locations, at high altitudes, not conducive to labour-intensive construction on-site. China instead plans, for speed, uniformity and that modern look, to truck everything out to the border, especially prefabricated concrete panels and girders, all speedily bolted and slotted together.

That in turn is assisted by bubbling the setting concrete to make the panels much lighter, yet still strong. The technology for inserting bubbles throughout a concrete panel relies on foaming chemicals derived from blood, and the new feedlots and slaughterhouses under construction in Tibet produce lots of blood.

From the planners’ viewpoint, it all fits. But it all needs labourers, lots of them, preferably year-round, trained, willing and able to move from construction site to site. Scarcity of labour was always a constraint on traditional modes of production, and now, on construction of modernity.

In China’s top cities, in high density districts, construction is highly mechanised, but expensive equipment isn’t the key in more scattered, low-density locations, especially in country that has long relied on hundreds of millions of semi-skilled workers willing to go wherever the work is. But they are no longer willing to come to Tibet, except for quick money, and then go back to their home province. The days of heroic pioneers volunteering to bring the light of revolution to the dark and backward places is long gone.

All of China’s grand plans for mines, dams, border villages and urban hubs depend on getting Tibetan men (and perhaps some women) off their lands and into construction work. From Beijing’s perspective, Tibet is a laggard, chronically languishing as all other provinces surge ahead. The standard incentives and extra subsidies that spur take-off elsewhere, including some Tibetan areas such as northern Amdo, just don’t work in Tibet. As a result Tibet is such an ongoing embarrassment that it is routinely omitted from official statistics, as an outlier that fails to leap at capitalist opportunities to get gloriously rich.

So, what is different this time round? “Guide the advantageous and characteristic enterprises to develop towards specialization, with Shigatse City and Shannan City [Tsethang] as the focus, develop labor service professional operation enterprises; through guidance, cancelling legal status for market violations, force the transformation and upgrading of farmers and herdsmen construction teams; Take advantage of the investment opportunities of major projects in Tibet during the 14th Five-Year Plan period to attract central enterprises and outstanding enterprises outside the region to settle in Tibet; Promote the development of construction enterprises for farmers and herdsmen through small and scattered projects in agricultural and pastoral areas; Change the business model of the enterprise, optimize the organizational structure and equity structure, encourage employee shareholding, technology shareholding, and investment cooperation to activate the vitality of the enterprise.”

Exnomads and exfarmers are to be encouraged to consider themselves stakeholders in an ownership society which makes a shareholding in a Chinese state-owned construction company into a stake in the enterprise’s success. Yet, despite talk of encouraging Tibetan construction companies, the corporations will be, as before, commercial spinoffs of local governments keen to cash in on the unending flow of funding from Beijing. In reality displaced Tibetans will be working, via layers of gangmaster contractors and subcontractors, for the rentier class of real estate speculators, the only folks in central Tibet who get seriously wealthy.

TAR 14th Plan: “Carry out practical construction skills training. Vigorously implement the skill improvement project for farmers and herdsmen, and establish education and training mechanism for emigrant workers, improve the quality of emigrant workers, give them opportunities for development, and improve the degree of organization of the transfer of employment of farmers and herdsmen. This has made construction workers an important impetus for the coordinated development of urban and rural areas. Organize training through various levels of housing and urban-rural development departments. Organize emigrant workers to bring local emigrant workers, self-training by enterprises, order-based training, etc.

“Focus on training farmers and herdsmen at the level of modernization as construction site managers, and for those farmers and herdsmen who have been employed in the construction field for a long time, increase the training of practical skills, and focus on increasing the willingness to work in the construction field for a long time.

“Raise the training intensity of farmers and herdsmen, comprehensively improve the skill level and quality of farmers and herdsmen, so that they can convert into construction industry workers. During the “14th Five-Year Plan” period, strive to pass three-year training. The number of farmers and herdsmen migrant workers in the region accounted for more than 30% of the local migrant workers, persisting for a long time, and increasing year by year. Promote the industrialization of construction workers.”

TOP DOWN DISPLACEMENT: TARGETING TIBET’S HIGHLANDERS

China’s 2021 White Paper on Tibet reveals a wider plan to concentrate the Tibetan population, away from higher altitudes, and also away from the borders with South Asia: “Tibet has relocated the impoverished to improve their living and working conditions. Poverty-stricken populations in Tibet are concentrated in the northern pastoral areas, the southern border areas, and the eastern areas along the Hengduan Mountains. All these areas are located at high altitudes. They are remote from vital markets and live in harsh conditions. Therefore, relocating the inhabitants of these areas is a rational solution to lift them out of poverty. Since 2016, Tibet has increased efforts to resettle the impoverished from inhospitable areas to places with better economic prospects. By 2020, Tibet had completed the construction of 964 relocation zones/sites for poverty alleviation in low-altitude, hospitable areas, where 266,000 poor were happy to resettle.”

It may take the full five years of this Plan culminating in 2025 to generate the schools providing a full three-year apprenticeship training, which no doubt will include compulsory learning of standard Chinese. More on that below.

Tibet is not Xinjiang. In Xinjiang there are several established labour intensive industries such as harvesting and spinning cotton, making clothing from cotton cloth, harvesting tomatoes, drying and processing them on a massive scale, and many more, all in chronic need of labour, until accumulated profits reach such heights that mechanisation takes over. Central Tibet has no such established industries to funnel the exnomads and exfarmers into.

If this official vision is realised, it will be achieved by coercion but also by incentivising young men into a new, gendered mode of mobility, from building site to site. The range of skillsets is wide, and Tibetans have had so many bad experiences of being ripped off by employers and the contractors through whom construction companies deal with workers. So the list of skills to be taught is wide, and the assurances to be offered make a long list in the TAR 14th Plan:

“The labor team has established enterprises that focus on professional operations such as woodworking, electrician, masonry, and steel bar making. Encourage existing professional enterprises to be specialized and refined, and form a new type of construction with complete specialties, reasonable division of labor.

“Establish an industry organization structure. According to the characteristics of the job, through the corresponding safety hygiene for front-line employees, training in production, professional ethics, theoretical knowledge and operational skills to enhance professional competence and ensure safety of production and engineering quality.

“Improve the protection mechanism for the rights and interests of construction workers. Attach great importance to the issue of migrant workers and further complete improving the real-name management system of construction workers, improve the wage payment security system, and increase the real-name system platform and construction of the interconnection and interoperability of the integrated market supervision platform, the formulation of the “Real-name Management System for Construction Workers in the Tibet Autonomous Region Management Implementation Rules“, through the establishment of special wage accounts, labor service fee payment, on-site staff attendance, online big data analysis and cloud computing of indicators such as wages, on behalf of the workers, with a crackdown on informal wage behavior. Continuously improve the wages and production and living conditions of migrant workers. Explore social insurance participation and payment methods compatible with the construction industry, and vigorously promote construction units to participate in work-related injuries insurance.”

Yet even if all of this comes to pass, Tibetans will still be the industrial proletariat, very seldom the owners of the construction corporations. For all the talk of training and protecting the new workforce, Tibetans will still be at the bottom of the ladder, with Han always above. Systemic inequality will persist. But there will be no option of returning to the clan’s pastures or fields, which will have been surrendered, in the name of conservation, or at best in the hands of a cooperative which leases the land to corporations using it to intensify production. For those who enter China’s construction labour market, there will be no going back.

“Real-name” management system is not to protect workers from being ripped off by employers who would say they never heard of them; it is an extension of grid management surveillance to ensure all Tibetan urban workers remain visible to the security state.

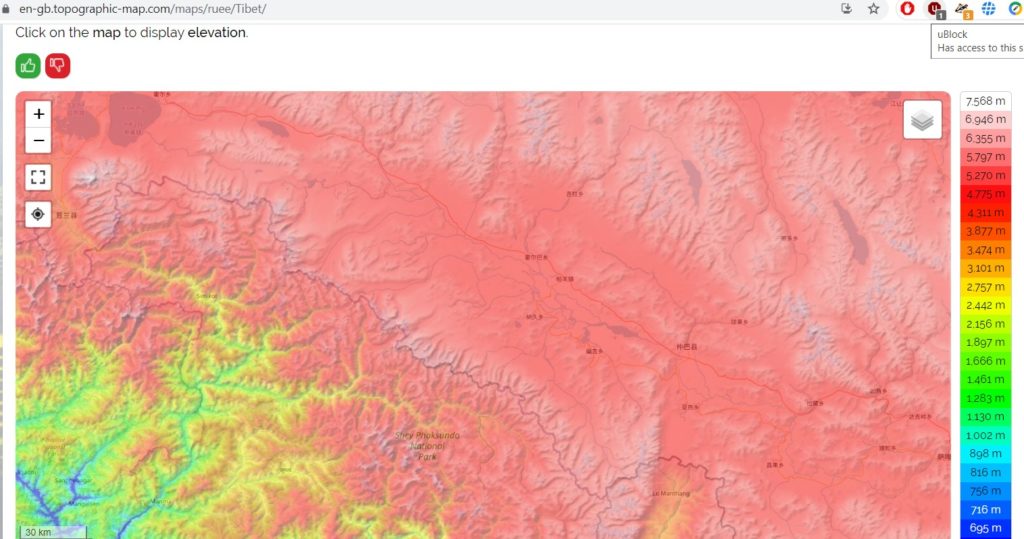

CONTOURING INTERNAL EXILE

China has decisively defined its clearance program altitudinally, from the top down, with a single carefully chosen metric, 4800m, as the magical number. Altitude has always featured as Tibet’s besetting sin, in Han eyes, an ineradicable stain that (until climate change changes everything) makes Tibet as best marginal, but mostly unliveable. The higher you go, the more Tibet deviates from what, for Han, is tolerable, given the ingrained but unconscious bias of all Han that normal is defined by lowland China’s arable lands.

“Since 2018, Tibet has launched a very high-altitude ecological relocation project. In Nyima County, Shuanghu County, Anduo County, 3 counties and 5 townships in Nagqu City, 1219 households and 5160 people have moved to Lhasa, Shannan and other places, and the altitude has decreased more than 1,300 metres.”

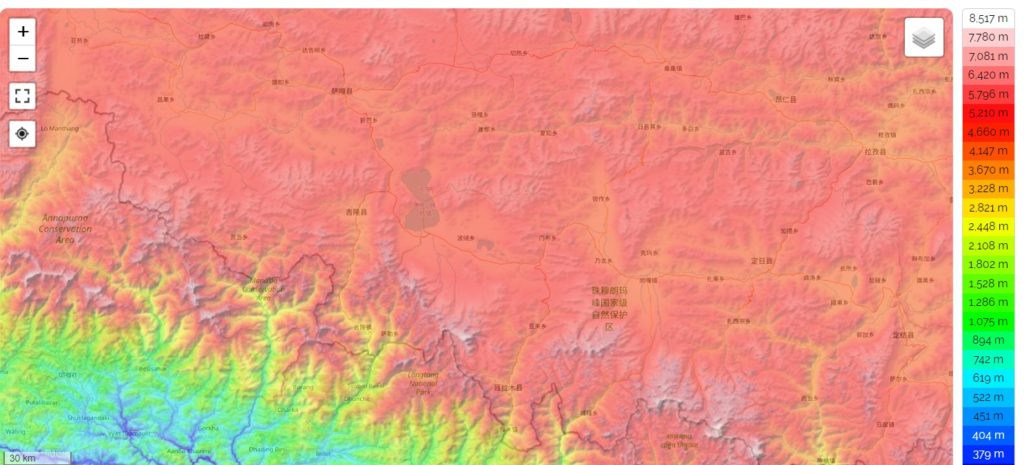

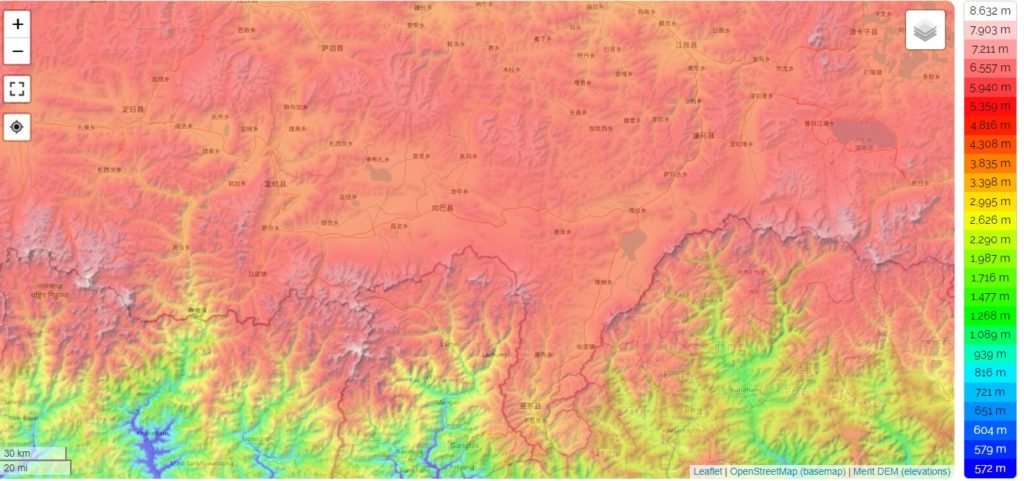

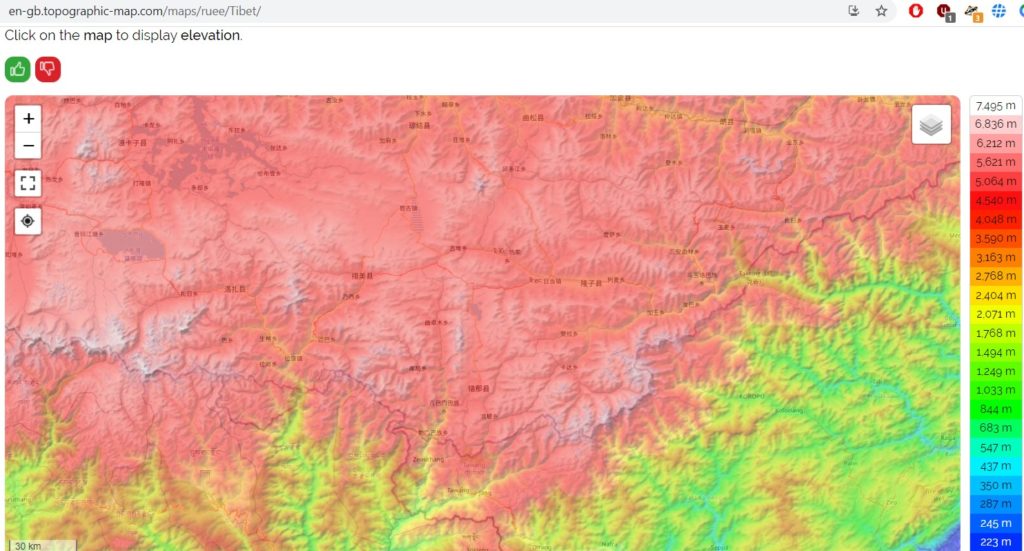

The cut-off isoline of 4800 m, is remarkably precise, so much so one might wonder whence it comes. Technically, drawing a relief map of the Tibetan Plateau with the 4800m contour line as a new Hu Huanyong line, is not difficult, especially in this time of satellite monitoring. But what is the significance of 4800m?

This is not the first time China has demarcated the civilised from the barbaric by a frontier drawn along a contour line. Close to a century ago, as Republican China pushed into Kham, the new province of Xikang -now Kandze and Ngawa prefectures of Sichuan- were defined by the 3600m contour line, below which wheat and barley can be grown, above is pastoral landscape.[3] China’s fixation on isoline as destiny is not new. Now the new 4800m line demarcates the human from the natural worlds, all so scientific.

Ascribing objective scientific truth to the 4800 number reveals itself, on the map, as aimed specifically at upper Tibet, the far west of Tibet, where Tibetan civilisations seems to have first developed, before slowly shifting east over centuries and millennia, as a drying climate made upper Tibet -as Tibetans call it- no longer able to sustain villages and irrigation channels, although their stone structures remain even now, thousands of years later, along with their rock art celebrating the gazelles and antelopes that mingled with their yaks and goats.

The 4800 number targets the Chang Tang, the empty plain of northern TAR, a huge alpine desert that flourishes in the summer monsoon season, attracting wildlife seeking safe birthing grounds, also Tibetan nomads with their herds. In more recent years the Chang Tang has attracted Chinese geologists, who report many big deposit finds that mostly remain too distant to be exploited.

It is in the Chang Tang that the party-state first encountered the global science of ecology, pioneered by wildlife ecologist George Schaller. Embedded in ecology is the assumption that all human presence in an ecosystem is by definition additional, problematic, a threat to ecosystem equilibrium, a predatory burden that necessitates regulation, maybe complete exclusion. In the history of ecology as a science, the idea of a definable ecosystem proved in practice to be remarkably hard to capture, even with humans excluded. Where does one ecosystem flourish, where is its boundary with a different ecosystem? What are the dominant species that define an ecosystem, differentiating it from another that is similar yet different? Despite endless transects, species counts, ennumerations and extrapolations, in practice ecologists struggled to capture the dynamics of even simple ecosystems with limited biodiversity. By definition, an ecosystem must be in equilibrium, that is what defines it as a distinct ecosystem, which always returns to its natural equilibrium even after natural disturbances such as an unusually hot or cold, dry or wet year.

Ecologists resisted any suggestion that there are areas, usually in the many drylands of the world, where there is no equilibrium, only great variability, to which plants, animals and customary human users have all adapted, whether by hunkering down or moving on until a more conducive season arrives. Where variability is characteristic, how can there be a definable ecosystem at all?

As if that wasn’t hard enough, there is the human presence. By definition, for most ecologists, all human use of landscapes, especially uplands and drylands, is predatory, imposing a burden that distorts ecosystems and upsets equilibrium. The simple solution was to exclude humans altogether from the effort to capture ecosystem dynamics. Whether the humans are predatory hunters, miners or customary pastoral custodians makes no difference. All human presence is problematic.

TOPOGRAPHY IS DESTINY

China’s simple solution today is to literally exclude all human presence above 4800m. Since all human presence is additional, supernumerary, contingent and predatory, the regulatory response deliberately makes no distinction between wildlife hunters, gold miners, highway builders, missile batteries, military barracks, and nomadic herders. Ban the lot. At least on paper.

This drastic oversimplification of actual environmental histories of Tibetan landscapes erases the tombs, dams, villages and rock art of thousands of years of earlier Tibetan use of these lands above 4800m; erases any legitimate ongoing seasonal use of the blooming summer meadows of these high deserts.

Total proscription of all human use serves the party-state, which strains to grasp what it reaches toward. In the first four decades of China’s six decades in command across the Tibetan Plateau, the Chang tang was penetrated only by heroic scientific exploration teams, geological prospecting parties and later by wildlife ecologists, in the wake of the fieldwork of George Schaller of the Wildlife Conservation Society based at Bronx Zoo.

It was Schaller who first raised the alarm about Tibetan nomads as predators upsetting the natural balance. Schaller, in many writings, always finds the nomads problematic, and becoming more so as they gained access to trucks, to set up summer grazing deep in the Chang Tang. This negative depiction chimed well with Schaller’s global audience, accustomed to the foundational assumptions of ecology, and emotionally identifying with the wildlife.

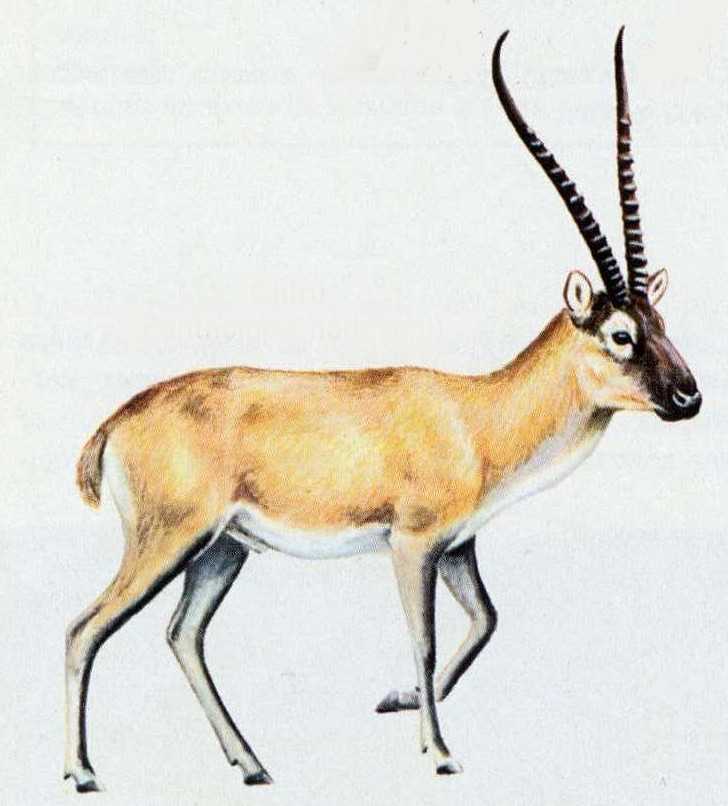

At the time -in the 1980s and 1990s- official China had little interest in Schaller or in the wildlife of upper Tibet, or actively catching the gangs of hunters who marauded upper Tibet, gunning down chiru antelopes in enormous numbers, for the handful of soft belly fur that is used to make shahtoosh shawls. In the decades prior to this century, most of Tibet was well beyond the frontier, a largely lawless land China knew little about, and cared less. Any effective policing of China’s wildlife protection laws was done by Tibetans of upper Tibet, intercepting and arresting the Hui Chinese Muslim gangs wherever they could, often at great risk to their own lives.

In this century it all started to change, as a wealthier China extended the reach of the state into all territories it claimed as sovereign. What had been out of sight, beyond the frontier, became scrutable. What the party-state could now for the first time see, it had to manage, that is how sovereignty is asserted. Schaller’s persistent alarm gradually found receptive ears, in contrast to earlier years, when he published descriptions of Tibetan cadres, empowered by party-state impunity, who mouthed conservation cliches in the office, but had freshly shot wildlife in their vehicles just outside.

Schaller was shocked, and made sure the world knew.[4] Leather jacketed Tibetan cadres had learned well from their Han superiors that dialectical materialism means conquering nature and the triumph of the human will.

[1] Wim van Spengen, The Geo-History of Long-Distance Trade in Tibet 1850-1950,The Tibet Journal , Summer 1995, Vol. 20, No. 2 (Summer 1995), pp. 18-63

Tina Harris, Geographical Diversions: Tibetan Trade, Global Transactions., University of Georgia Press, 2013.

Tea-horse trade in Kham: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wLLPh8nQy68&t=917s

[2] Liv Timmermann and Carsten Smith-Hall, Commercial Medicinal Plant Collection Is Transforming High-altitude Livelihoods in the Himalayas, Mountain Research and Development Vol 39 No 3 Aug 2019: R13–R21

Kamal Adhikari, Ethnobotany, Commercialisation and Climate Change: consequences of the exploitation of yarsagumba in Nepal, European Bulletin Of Himalayan Research, 49, 2017, 35-58

[3] Mark Frank: 3600 Meters: The Grain Line as a Lens on the History of Han-Tibetan Relations, 2021, https://tibet.columbia.edu/events/life-along-river-interactions-between-human-societies-and-valley-environments-convergence

[4] George Schaller, Tibet’s Hidden Wilderness: Wildlife and Nomads of the Chang Tang Reserve, Abrams, 1997, 91