Blog four in a series on Tibet in 2021 4/8

HYDROPOWER INDUSTRY REGAINS ITS MOJO

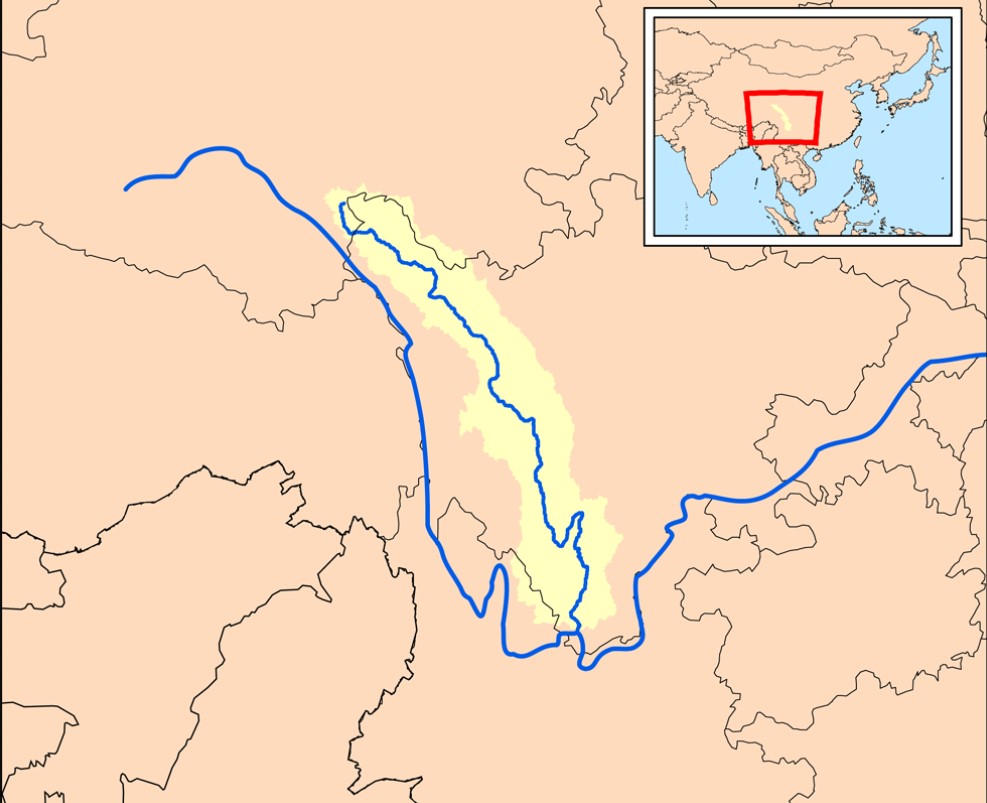

China is far from done with dam building, on all the major rivers of Asia that rise in Tibet. This is more than a balancing of supply and demand; the dam plans were meant to knit Tibet into the fabric of China, inextricably linked by long distance power grids; a nation building exercise by a party-state out to make Tibet a profit centre for China, linked by cables west to east, a single cloth.

If nation building remains as Beijing’s dominant narrative, central leaders may continue to allocate investment capital to build more dams, even if much of the electricity they generate is wasted, as has happened year after year on the Tibetan rivers of Kham. But the business case has collapsed. Hydro engineers in Sichuan report that: “Under existing policies, research has shown that the basic costs of electricity from the typical plants in Tibet and the Sichuan-Yunnan Tibetan area are high and uncompetitive, so that investment enthusiasm for hydropower companies will wane and water resource utilisation will be affected.”[1]

So it now seems quite possible that if Tibetans can slow dam construction, the dam builders might just pack up and go home. It is now a question of whether Tibetan communities, often in remote and rugged gorges, can persist with their stubborn resistance to nationalisation and globalisation.

The declaration that China has decided to live with damming a mere 60 per cent of the measured hydropower potential of all the rivers, is a turning point. Until now, especially when -in the 1980s and 90s- most of the CCP Politburo Standing Committee were engineers, it was axiomatic that China must impound as close to 100% of potential hydropower as possible. This was a strategic imperative.

Settling for 60% is a sign of an industry maturing; a recognition that the remaining 40% is in very difficult, earthquake-prone terrain. On every major river, the easiest dams have been built first, below Tibet. Only gradually has the damming moved upriver, into the canyons, ravines and precipitous landscapes of Kham. This seems to be the cusp of something different.

Or maybe not. If the hydrodams are solely to meet China’s electricity needs, the 13 arguments above apply. If, however, central leaders persist with their fixation on binding Tibet inextricably to China by power grids (made of copper from mining Tibet), and also exporting electricity, then the transition away from hydro may stall.

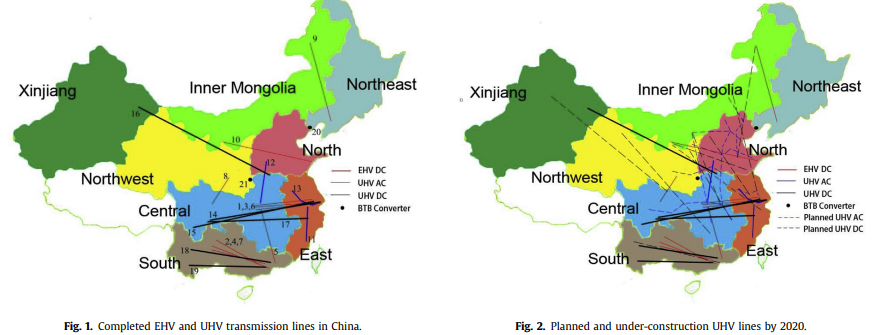

Even if China’s electricity demand can be met without damming Tibet much more than it is now, China’s ambitious Global Energy Interconnection scheme could see electricity form Tibet exported, initially to South Asia, eventually as far as Europe.[2] This is technically feasible, as a 2017 independent study by the European Commission has confirmed. By converting AC electricity to DC, China has mastered the technologies of transmitting electricity over vast distances, with little dissipation, and at extraordinarily high voltages. It can be done.

If the Global Energy Interconnection, built worldwide by China, were to be realised, it would rely on Tibet as the primary source, not only through hydro damming but by adding wind and solar energy generated in Tibet as well. It sounds improbable, but according to reputable think tanks such as the Atlantic Council, it can be done.

Powering the whole of Eurasia from Tibet is technically feasible, not only according to China’s State Grid Corporation and its advocacy arm GEIDCO, the grandly named Global Energy Interconnection Development Cooperation Organisation; the European Commission also found it can technically be done. Is this really the twilight glow of an industry that once dominated China’s hydraulic economy, but is now flaming out?

Even the hydro dammers are switching to wind and solar power, in Tibet. Yulong Hydropower Corporation, which takes the entire Kham Kandze Nyagchu catchment as its fiefdom, now says it has dozens of wind and solar farms under way, many in Tibet.

China’s hydropower potential has been calculated as 2329 terra watt hours (tWh).[3] As climate change steadily makes the Tibetan Plateau wetter, hydropower potential across Tibet is likely to grow. This is what has always driven dam building, giving it an urgency. It becomes a necessity to impound and exploit that potential; to fail to do so would be to let it go to waste, as those lazy Tibetans did.

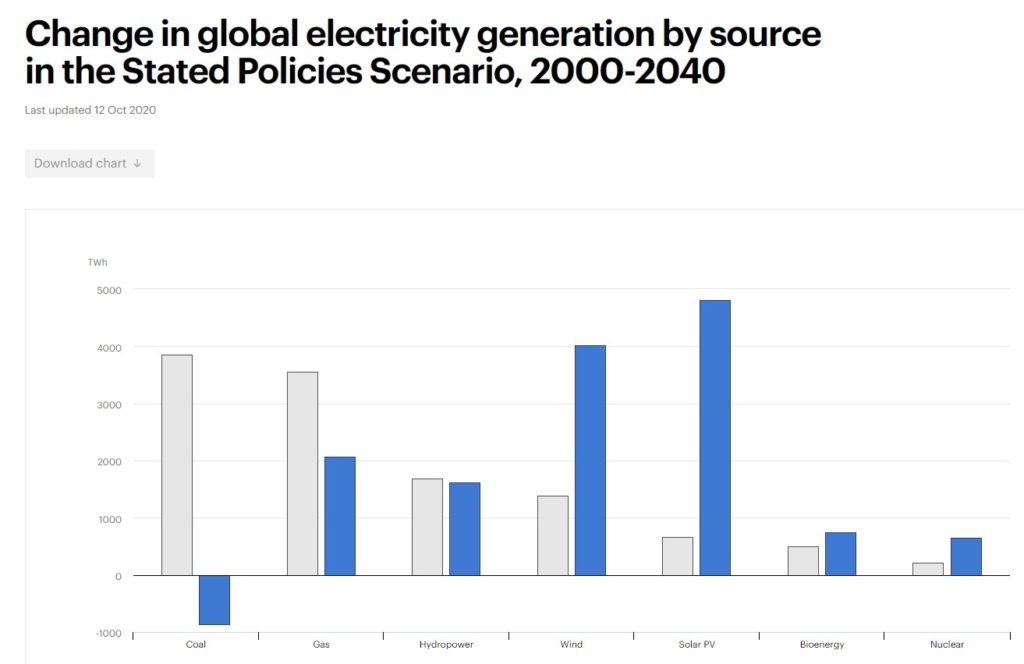

That sense of pioneering urgency and inevitability has at last faded. After the twilight, a new dawn shows the landscape in a new light, full of solar wind potential wherever you look, but especially in Tibet and Xinjiang. Solar and wind are technologies whose time is now; the prospect that six decades from now a wetter Tibet will have greater hydropower potential is of no consequence.

REINVENTING HYDRO FOR AN ERA OF UNPREDICTABILITY

Sixty percent of China’s estimated hydropower potential is 1397 tWh per year. Maybe that’s enough, time to move on.

Yet China’s hydro engineers aren’t done yet. They now argue for new ways hydro dams could be used to help with one of the difficulties of the turn to solar and wind, which is the mismatch between when electricity demand peaks, and when the sun shines and the wind blows. Electricity can’t be stockpiled in advance of demand, production and consumption are simultaneous. Batteries are a way of stockpiling, but battery technologies are still basic and inadequate to the scale of the task. This is where hydrodams make their renewed pitch.

New hydrodams could be built to deliver electricity to the grid only at peak demand times; the rest of the time their spinning turbines are used to pump water back up behind the dam wall. This effectively makes the hydro project a giant battery. It’s called pumped storage. Tibet has long had just such a dam, the sacred Yamdrok Yumtso lake was designed as a pumped storage dam linked to the Yarlung Tsangpo below, providing peak hour electricity to Lhasa. Nobody asked the Tibetans.

The latest pitch by the dam promoters is to use the overabundant summer monsoon rush of water through the turbines into a different kind of battery, using excess electricity generation to make hydrogen, to be stored for making energy when the demand peaks.[4] Technically, this is barely feasible, and may perhaps one day happen, but not soon.

Neither of these dam-cum-battery ideas are likely to slow the exit from damming as the acme of “ecological civilisation with Chinese characteristics.” China is moving on to the next big thing.

Many who made their careers in dam building are yet to notice this paradigm shift, and continue to argue for even more central subsidies, concessional loans, protracted loan repayment periods and several other costly incentives, to reduce the costs of generating hydropower in Kham, as if nothing has changed. They are also adept at pressing Beijing’s buttons: “Tibet and the four-province Tibetan areas (the Tibetan autonomous areas of Qinghai, Sichuan, Yunnan and Gansu) are the most impoverished areas in China and have the worst poverty levels of 14 concentrated and extremely poor areas of the country, where the main factors leading to poverty are adverse natural conditions, limited power industry, weak infrastructure and underdeveloped social institutions. Maintaining the stability and development of Tibet and the four-province Tibetan areas is of great strategic importance to China. Among these areas, Tibet and the Sichuan-Yunnan Tibetan area are extremely rich in hydropower resources. Indeed, the capacity of the water resources that are technically exploitable in Tibet corresponds to 174 billion watts, meaning it ranks first in China: however, the installed capacity of the built hydropower plants is around 2.3 billion watts, i.e., just 1.3% of the exploitable amount.”[5]

Fortunately, Beijing seems deaf to these familiar special pleadings for more and more subsidies and price distortions. Or is it? The Seventh Tibetwork Forum, in Beijing in August 2020, urged accelerating development throughout all Tibetan areas. The specific directives issued by the Tibetwork Forum, the highest level of party-state coordinated campaign planning, are not immediately made public. Neican 内参 or “internal reference documents” are limited circulation reports only for the eyes of high-ranking officials in China, dealing with topics deemed too sensitive for public consumption. Hopefully, we will know soon whether dam building in Tibet will persist, even when other provinces have no interest in importing electricity from Tibet when they can build their own coal fired power stations, and make more money.

The dam builders do have a voice, and take every opportunity to insist the dams they designed must be built. Their professional associations promote more dams, knowing well the fame of heroic pioneering engineers who designed them, far up in the mountainous valleys of Kham, masters of the conquest of nature. Huge state owned corporations have carved out territories in Tibet, each named after the river they claim exclusive development rights to own.

FATE OF A LAW, FATE OF THE MOTHER RIVER

In this complex terrain the Yangtze River Basin Protection Law has by now gone through several iterations, following many consultations, mostly with the various arms of the party-state that compete with each other. Following the tortuous path of this legislation is easy, because the NPC Observer is tracking its progress, through a first and second draft, ready for rubber stamping at the end of December 2020..

The official second draft does indeed claim to embrace the river in its entirety, including the upper third, in Tibet. By contrast, on the Za Chu/Mekong/Lancang, the Tibetan upper third is routinely omitted from consideration or voice, often not even shown on maps, such as those published by the Greater Mekong Subregion transboundary consortium of riverine countries , established by the Asian Development Bank.

Speaking for the entire Dri Chu/Yangtze river, Article 20 of this second draft strongly proclaims national over sectional interests: “Article 20: The state strengthens the management of the development and utilization of hydropower resources and strictly restricts building of large and medium-sized hydropower projects in the Yangtze River Basin.”

However, reflecting the many powerful stakeholders and their vested interests, the draft law immediately reverses the direction of flow: “If construction is needed, because of the national development strategy and national economy and people’s livelihood, it shall be scientifically demonstrated and reported to the State Council for approval.” Back to square one.

What sort of law is this? Definitely not a law that can be litigated, when two consecutive sentences are so contradictory. Even if it is read as a policy statement, it is incoherent. The Dri Chu pays the price for the compulsory silence of the Tibetans.

Does this new law create new spaces for Tibetans to speak? Will Tibetans displaced from their ancestral lands within the Yangtze/Sanjiangyuan catchment be able to protect their record as custodians of sustainability and of water purity, and thus protect their land rights?

The formal process of drafting laws in China, as in other countries, includes a period of consultation, during which time Tibetans could theoretically speak up on issues affecting them, such as the future governance of the Yangtze. While the CCP insists it alone is always right, the state has quite extensive procedures for input from the whole range of stakeholders. The Yangtze Protection Law draft was issued, for consultation, in late 2019, with the explicit invitation: “for the draft revision to the Yangtze River Protection Law includes the following options: “state organs and their employees” [国家机关及其工作人员], “public institutions, social groups, and their employees” [事业机关、社会团体及其工作人员], “persons living in the Yangtze River basin” [长江流域所在地人员]; and “other” [其他]. Comments can also be mailed to the NPCSC Legislative Affairs Commission [全国人大常委会法制工作委员会] at the following address: 北京市西城区前门西大街1号 邮编: 100805; No. 1 West Qianmen Avenue, Xicheng District, Beijing 100805. Please clearly write “[BILL NAME IN CHINESE]征求意见” on the envelope.”

Is this just an elaborate charade? The whole process took over a year, the first draft became a second draft, which was published for further comment. That second draft included Article 20, quoted above, calling both for a winding down of hydro damming, and for damming to be done scientifically. That contradiction did not survive the second round of consultations.

Article 20 began life as a bold assertion of the national interest in a healthy river, over the provincial and local interests in extracting water, electricity and profit from the Yangtze: “The state strengthens the management of the development and utilization of hydropower resources and strictly restricts building of large and medium-sized hydropower projects in the Yangtze River Basin.”

When this legislation was finally enacted, that crucial sentence was dropped. The hydro engineer old guard won. They lobbied hard to get the national government’s idea of national interest to back off, leaving room for more local interests, and they won the dropping of the sole clause that could have spared Kham from further damming.

Some of that lobbying was done in public. On the world’s largest online app, Weixin (Wechat) the hydro engineers stated their case, and dismissed critics of hydro damming as “People with ulterior motives at home and abroad who have been demonizing hydropower for a long time, and misled non-hydropower experts and media personnel.”

The engineers had three things going for them:

- the compulsory silence of the Khampa Tibetans and Yi minority ethnicity further downriver,

- the reification of narrowly defined “science” as the sole criterion of policy,

- and the long history of hero worshipping hydro engineers (and geologists) as pioneer shock troops of conquering the frontiers, taming wild rivers and sacrificing for the revolution.

Of these three, the old guard spoke publicly of only one: the scientific/patriotic case for ongoing damming. They remained silent about Tibetan silence: why draw attention to mandatory absence? They also said little about their revolutionary credentials as model workers for socialist construction, perhaps because that reputation, in today’s corporate/consumer China, is on the wane.

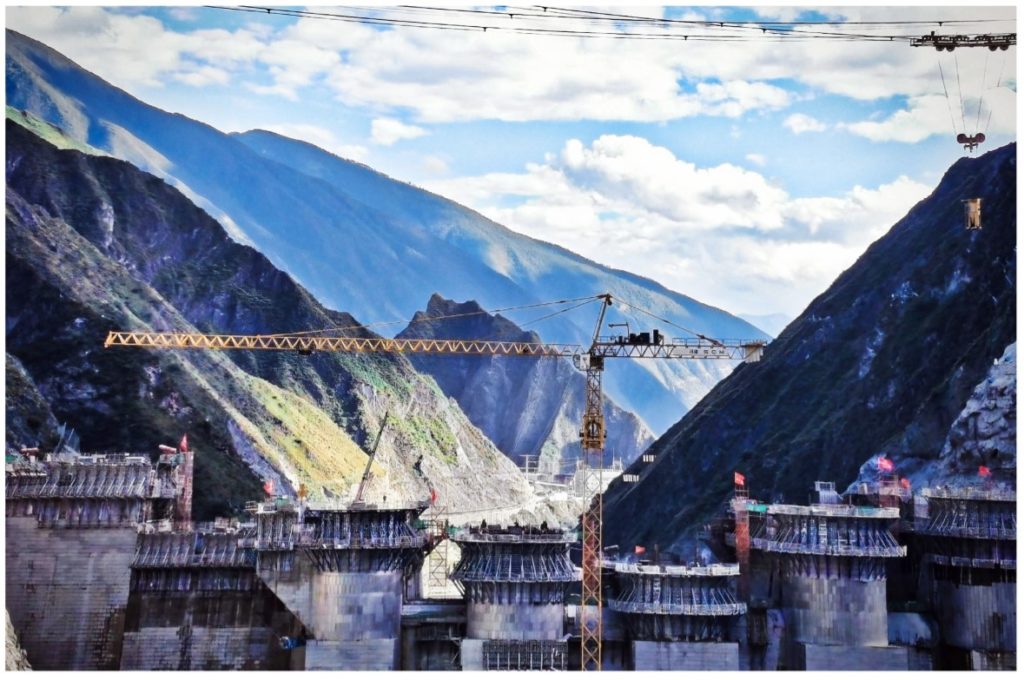

But they went full bore on hydro damming as science, even if it’s a science which ignores the sciences of landslides, earthquakes, fish kills, sedimentation and other dangers of dams. Hydrodamming remains, as ever, the rational way forward, the tech needed to reduce carbon emissions and Beijing’s smog. Blending science and fealty to Xi Jinping, the hydro engineers invoke the glory of the massive Wudongde dam on the Yangtze, exactly where the Jinsha/Yangtze flows from Yunnan into Sichuan, due to begin full operation by end 2021 after a decade of construction. This megadam, in the lands of the Yi minority nationality below Tibet, is in a gorge similar to the terrain in Kham, requiring one of the highest dam walls in the world, and two separate underground turbine chambers, one to send electricity to Yunnan, the other to Sichuan, as each province has invested in a 15% stake. That’s classic hydro-politics, locking in the biggest stakeholders, ensuring each gets exactly equal generating capacity.

Wudongde, on the eve of its triumphant completion, must not signal the end of the age of hydro, which is why Xi Jinping himself in June 2020 commended Wudongde for its capacity to transmit electricity across China, west to east, to the coastal factory belt. So the hydro-engineers remind us. Let there be many more Wudongdes, marching upriver into Tibet: ”bravely climb the new peak of science and technology, complete the follow-up project construction tasks with high standards and high quality, and strive to make the Wudongde Hydropower Station a high-quality project. We must adhere to ecological priority and green development, advance the development of Jinsha River hydropower resources in a scientific and orderly manner, and promote the development and protection of the Jinsha River Basin in protection, so as to better benefit the people.”

Since this is all about politics, the dammers shamelessly push patriotism.. Having invoked Xi Jinping, they expound on China’s global role as hydro dam builder, as a source of national pride: “It is the strong support of the party and the government and the joint efforts of generations of water conservancy and hydropower that we have stepped to the forefront of the world and won high recognition from developing countries and even developed countries.”

They also warn explicitly that any wording in the Yangtze Protection Law restricting hydro dam construction will make it harder to get dams built on the Yarlung Tsangpo/Brahmaputra: “The Yarlung Zangbo River is a cross-border river and a sensitive river that has received close attention from the international community. Regarding the wording of the Yangtze River legislation on hydropower, full consideration should be given to rigor, so as to avoid external public opinion using superficial meaning and over-interpreting it.”

Then comes a clincher. If China is to catch up to the West, as is its right, electricity consumption will continue to grow fast, but not from coal burning: “my country is still in the middle and late stages of industrialization and rapid urbanization. In order to achieve the “two centenary” goals [in 2049], it is expected that my country’s economy will maintain a medium-to-high-speed growth in the next 30 years, and the growth rate of electricity demand exceeds the growth rate of GDP. With the acceleration of urbanization and electrification, especially the improvement of people’s living standards and the overall acceleration of electric energy substitution, my country’s electricity demand will grow rapidly in the future for a long time.” If all those hundreds of millions of urban consumers in China’s east won’t be able to get more power from Inner Mongolian coal, it must now come from hydro on the great rivers pouring from Tibet.

So the hydro dammers make their demand: “Therefore, the term “strict restriction” mentioned in Article 20 of the draft article is seriously inappropriate in the construction of large and medium-sized hydropower projects in the Yangtze River Basin. It is completely contrary to the context of “implementation of hydropower development on the lower reaches of the Yarlung Zangbo River” mentioned in the14th Five-Year Plan planning proposal.”

That public advocacy was published with perfect timing, on 21 December 2020, five days prior to the National People’s Congress legislative session. The NPC caved, the offending sentence asserting national over sectional interest was quietly deleted.

Some say there is no political debate in China. Not so. Powerful lobbies routinely outflank national legislators. But did any among the fragmented Yi or Tibetans have a say? Who can match the loud voice of the patriotic old red guard of hydro dammers, when the slightest dissent is criminalised as “picking quarrels and provoking trouble”?

The Yangtze Protection Law has failed, at the last minute, to protect Tibetans and other minority nationalities whose voices and concerns are routinely silenced. China too has failed to enact a law that does what its name says, to protect the entire river, from source to mouth. The Mother river of China is to remain fragmented, one law for below, dammers’ law for upriver.

The drive for a coherent watershed-wide policy for the Dri Chu/Jinsha/Yangtze actually began with Xi Jinping in 2016, as part of his centralisation push. In January 2016: “No more large development projects will be launched along the Yangtze River, President Xi Jinping said on Tuesday at a top-level meeting to finalize guidelines for the economic belt along China’s longest river.”

It took close to five years for the hydro dammers to ensure large dam development projects on the upper Yangtze can still go ahead. They won, Xi Jinping lost that one.

Who can voice a river? Who speaks for nature?

May be Tibetans in diaspora can speak up, since close to one billion dollars of the $15bn Wudongde budget was spent on Western suppliers of core technologies: the turbines, contracted to GE (General Electric) and the Austrian manufacturer Voith, supplier to the controversial Yamdrok Tso dam back in the 1990s. Another supplier of key technologies is Texas-based AZZ.

This seems to be a moment for superficial over-interpretation.

[1] Yue Liu et al, Competitiveness of Hydropower Price, 2018

[2] https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/54361687-0702-11e8-b8f5-01aa75ed71a1/language-en

Ardelean, M. et al., Optimal paths for electricity interconnections between Central Asia and Europe, European Commission JRC Science for Policy Report 2020

[3] Y. Zhou et al, A comprehensive view of global potential for hydro-generated electricity, Energy and Environmental Science, 2015, 8, 2622

[4] Olusola Bamisile , Jian Li , Qi Huang et al, Environmental impact of hydrogen production from Southwest China’s hydro power water abandonment control, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, Volume 45, Issue 46, 21 September 2020, 25587-25598

[5] Liu, Competitiveness of Hydropower Price, 2018