ON THE RADAR OR OVER THE HORIZON? TIBET IN A SECURITIZED WORLD

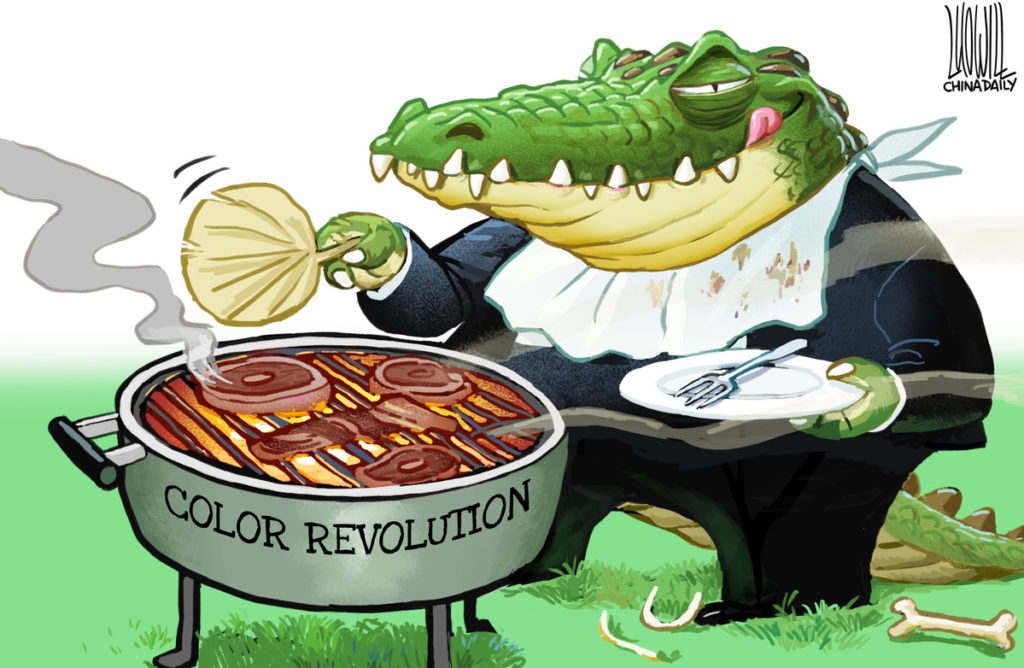

In recent times, many colour revolutions have erupted. In so many countries predatory regimes afflict their own citizens. They routinely and coercively extract rents from the poor to transfer wealth and concentrated power to the rich.

The point at which oppressed populations lose their fear, and stand up to their oppressors, willing to endure state violence to end a despised regime, is seldom foreseen. Security analysts often struggle to comprehend the disillusion and despair that makes whole populations rise up against bad governments, rising despite brutal crackdowns by the military and special forces.

Regimes that came to power through revolution especially dread the prospect that revolution then becomes legitimate when the regime fails the people. China is more fearful of a colour revolution yánsè gémìng 颜色革命 than any other threat.

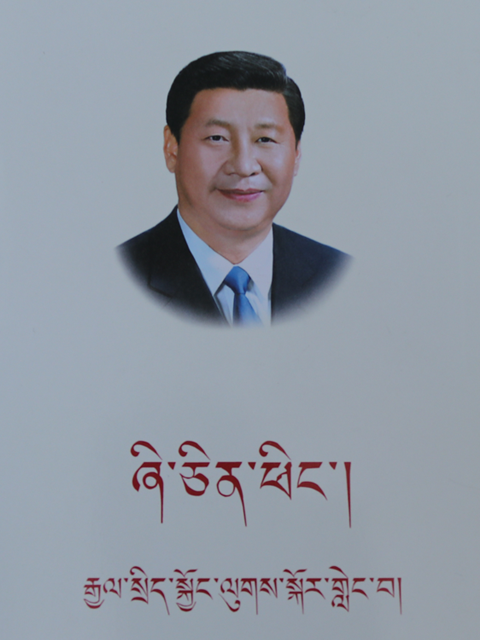

Xi Jinping’s extreme concentration of power has alienated China’s neighbouring client states, deeply worried competitors.

Inside China, it has raised tensions and contradictions among the people. The many fears of central leaders have led China to mass detention of 10% to 20% of the entire Uighur population in Xinjiang, on the futile assumption that forcing people to parrot official slogans, hour after hour, for days, weeks and even years on end, is an effective way of deradicalizing alienated minds. Far from being skilful and effective reorientation of values, the state violence in Xinjiang will produce only bitterness. The party-state demands all citizens love it; but love cannot be kindled by violence.

ACCELERATED ASSIMILATION

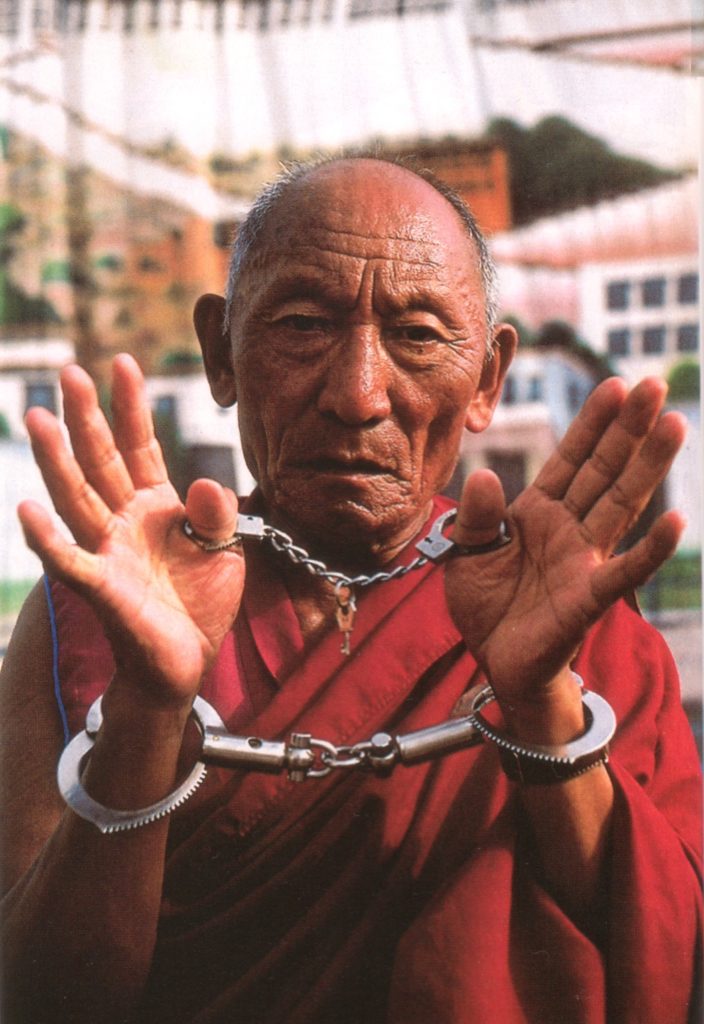

The securitised world should now be looking more closely at Tibet, where the control techniques applied in Xinjiang were first trialled, where the forbearance of a Buddhist population is tested to its limits.

All the signs of an incipient colour revolution can be observed in Tibet, with no way of knowing what and when the spark ignites unquenchable fire. Xinjiang shows China is capable of so blinding itself, with racist contempt for those who refuse to assimilate, that it provokes the contention it most fears. Will China repeat the same mistakes, and crimes against humanity, it commits in Xinjiang?

Coercive, compulsory assimilation of nonHan ethnicities is rather vaguely known as “second-generation ethnic policy”, 第二代民族政策 dì èr dài mínzú zhèngcè . This signifies a decisive turn against the “first generation” policy, modelled on the Soviet Union, of allocating legal, territorialised autonomy to minorities in their homelands. That is so 1980s. China has now hardened its heart against those intractable minorities of the far west, who have never felt included as equals in a country with a Han supermajority, aka Chinese characteristics. Official media now routinely depicts those who resist assimilation as ungrateful, backward, primitive and dangerous.

This hardening of prejudicial stereotypes can be documented in depth, a process spanning decades, as China’s central leaders paint themselves into corners. They are hemmed in further by angry wolf warrior Han social media trolls, who were fed, decade after decade, the propaganda line that these minority nationalities are untrustworthy, loyal to international cultures, prone to violence and terrorism. Securitisation magnifies suspicious mindsets.

THE CORE LEADER MAKES TIBET CORE BUSINESS

This is the present danger. It places Tibet at the forefront, straddling fault lines that can at any time trigger an earthquake. We need to know more about the situation on the ground, in Tibet, a geography the size of Western Europe, at the heart of Eurasia.

Globally China has repeatedly shown itself willing, even eager, to bully any country not its equal in size and power, projecting its power well beyond its effective grasp. Within China, the party-state regime is even more convinced it has free rein to do whatever it takes to quell the people, and has the surveillance technologies to do it. In a time of renewed competitive nationalisms, China asserts more vigorously than ever that any international concern over Xinjiang or Tibet is illegitimate interference in China’s sovereign right to oppress its citizens. This generates the dangerous illusion that the party-state is free to do whatever it wants within its borders, and perhaps beyond them.

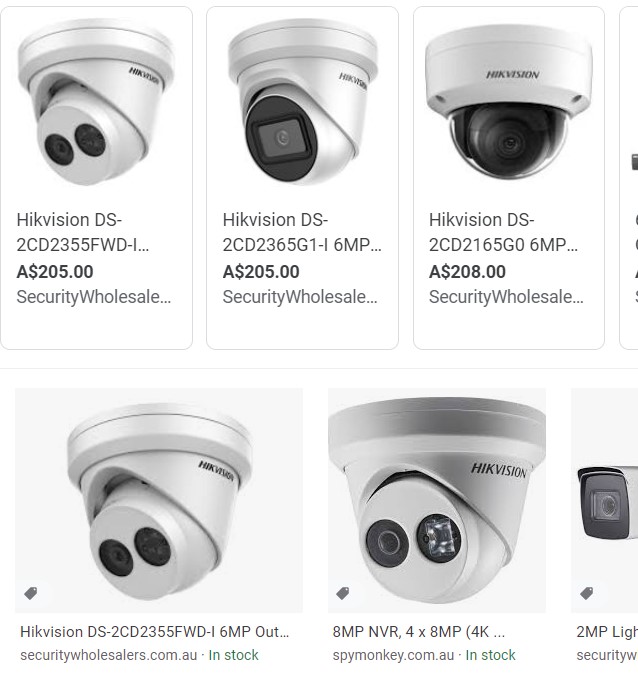

China’s faith in the accuracy and omniscience of surveillance tech, and in algorithms capable of predicting contestation of state power, is misplaced. The algorithms are laden with racist prejudices: garbage out. In Xinjiang men with beards and women with scarves are automatically categorised as having terrorist inclinations, to be dealt with by predictive policing, supposedly capable of predicting and thus interdicting criminal behaviour before the putative perpetrator is even consciously aware of any such intention. This is delusional. The result in Xinjiang is bitterness at a state willing to itself terrorise entire nationalities.

Further intensification of predictive policing algorithmically-driven arrests and detentions is now under way in Tibet, following the Seventh Tibetwork Forum held in Beijing in the last days of August 2020. Tibetwork is a known category within the security state, with its own “laws” to be learned and applied on mass scale, across all five Chinese provinces where Tibetan “autonomous” designated counties, prefectures and regions spread across one quarter of China.

Tibetwork Forums are rare, the last was in 2015. They are not only attempts at whole-of-government coordination, they are meant to mobilise mass campaigns 运动 yundong, to sweep all resistance away, for the triumph of the official line. It is not yet clear what secret directives are being issued to local governments in Tibetan area. Yet the signs are clear: the mass line of recent years, of intense pressure on educated Tibetans, to denounce their own culture and culture heroes, is correct and is to be intensified. This pressure to betray becomes intolerable at a certain point, even for Buddhists with deep training in mental flexibility and resilience. The official paranoid style insists all problems in Tibet are instigated from abroad, so no Tibetan grievances, or petitions for Chines law to apply in Tibet, are permitted. The exclusion of Tibetan critiques of policy and its implementation stifles any Tibetan presence in the public sphere, beyond singing and dancing on tv. At a certain point this stifling becomes unbearable.

One of the specific outcomes of the 2020 Tibetwork Forum was to extend this silencing of public utterances by Tibetan lamas and widely trusted leaders, even in mediating local community disputes. Traditionally, clans of pastoralists disputing land rights turned to local lamas know to be unbiased, trustworthy and skilled negotiators capable of cooling hot heads. The lamas would use their reputation for fairness, their persuasive abilities, their rhetorical use of logic, to cut through the feuds and restore cooperation, in traditionally stateless societies with not only no black letter law but no concept of law. So the anthropologists, such as Fernanda Pirie at Oxford Law School, tell us.[1]

Yet even these community based informal mediation processes, among Tibetans, in Tibetan, were explicitly banned by the 2020 Seventh Tibetwork Forum. The party-state insists it alone is the sole legal authority, even though it has no interest in resolving community disputations, until they are so entrenched the situation is unworkable. The heavy hand of the party-state defends its exclusive prerogative, its sole right to violence, yet in the eyes of feuding communities, it delivers no justice. Again, there has to be a breaking point.

Contention over pasturage rights in remote pastoral districts of low population density is not going to keep China’s security state awake at night. Such “mass incidents” can be quelled. There is a reason why there is a PLA garrison on the outskirts of every Tibetan town.

TIBET BECOMES A GEOSTRATEGIC ASSET

Of much greater concern for a security state hardwired to see all contention as an existential threat to China as a unitary state, is the rising dismay, in densely populated eastern Tibet, at the intensifying incursions of Chinese nation-building projects, including expressway toll roads, high speed railways, hydropower dams and power grids marching across sacred landscapes. China’s mastery of infrastructure technologies projects the power of the party-state onto remote landscapes as never before. The mining of Tibet’s abundant resources, especially copper, gold, silver and molybdenum is also intensifying. That in turn exacerbates demand for hydropower, immigrant Han workforces, and wicked problems of mine tailings waste disposal in rugged terrain above watersheds of most of the rivers of Asia.

These combined impacts are of geostrategic significance, both because of the many transboundary rivers originating in Tibet, and because China is accelerating its pace and scale of nation building infrastructure construction, as never before, and the Seventh Tibetwork Forum signalled further intensification.

Tibetwork is a recognised specialty within the security state, a civilising mission uncannily akin to 19th century European imperialist rhetorics. “Wu Yingjie 吴英杰 [CCP Secretary in Tibet] pointed out that in the past 55 years, under the strong leadership of the Chinese Communist Party, the people of all ethnic groups in Tibet have made the impossible possible. The society has achieved a historic leap from a feudal serf system to a socialist system, and development has achieved a transition from poverty and backwardness to civilization. The great leap of progress has written a strong and colorful stroke on the historical picture scroll of the Chinese nation’s continuous self-improvement. 吴英杰指出,55年来,在中国共产党坚强领导下,西藏各族人民把不可能变成了可能,社会实现了由封建农奴制度向社会主义制度的历史性飞跃,发展实现了由贫穷落后向文明进步的伟大跨越,在中华民族自强不息的历史画卷上写下了浓墨重彩的一笔.”

OVER THE HORIZON INTEL

Thus far, the focus has been on Tibet as a whole. Strategic analysts will find they need to know about these fault lines before the earthquake. To understand where and when Tibetan distress will reach crisis point requires localised focus. Across a plateau of 2.5 million square kilometres, local circumstances vary enormously, likewise the capacity of the state to inscribe its power on landscapes varies greatly.

In hindsight, one of the triggers of the Xinjiang debacle was the transfer,to Xinjiang roughly a decade ago, of dirty industries no longer tolerable by the mobilised, protesting citizenry of China’s big cities. In northern Xinjiang there has been an intensification of coal fired power station construction, the relocation of cotton production, processing and cloth manufacture, a proliferation of power hungry aluminium smelters, and the military-industrial dominance of the Xinjiang Production & Construction Corps drove small Uighur businesses to bankruptcy. In southern Xinjiang, which was at first much less affected by colonisation and industrialisation, new oil field finds led to massively upscaled extraction, immigrant influx and the destruction of old oasis towns in the name of modernisation. In hindsight, these were all triggers for the Uighur protests that erupted in 2009 and since, met by overwhelming but counter-productive state violence. Few saw this coming, which made it easier for the party-state to blame it all on Islamic fundamentalist terrorism.

The world should not fail to recognise the same tensions building in Tibet. Hindsight is too late. Tibet is not at all an unknown unknown.

ACCELERATING TOWARDS A CLIFF

Acceleration is the hallmark of the Anthropocene era we now live in. Acceleration was the key deliverable of the Seventh Tibetwork Forum. For Tibetans this means acceleration of urbanisation, rural depopulation, intensified resource extraction and power grid linkage of Tibet with coastal China, knitting Tibet into the fabric of China forever. The cumulative impact of these multiple accelerations deeply alarms Tibetans, as is evident in their social media posts and online publications, even while acknowledging the material comforts of town life.

Tibet’s customary culture, attitudes towards landscapes, livelihoods, the purpose of life, the value of wildlife and rivers are all challenged as never before. Party-state “second generation” ethnic policy theorists foresee increased resistance but dismiss it in advance as the growing pains of inevitable modernity, which central leaders should ignore. Deafness ensues. This insouciance is dangerous, it further hardens hearts in Beijing against remote communities who are increasingly aware of China’s laws, which in practice don’t protect them.

The ingredients of crisis are accumulating, and it will not suffice to say, as China does officially, that development has its laws, is a universal path that China assiduously follows, and in the long run all will be well, as urbanisation loosens social ties, and people transfer their loyalty to Beijing, to the distant nation-state. The same productivist, developmentalist rhetoric was applied to Xinjiang, with disastrous, self-defeating results.

The party-state insists its accelerating agenda of development is a win-win, including Tibetans who are thus lifted out of poverty. This propaganda rhetoric obscures how the various nation-building projects are experienced by Tibetan communities. When cadres come to a village to announce the mandatory expulsion of a quota of local pastoralist families to distant urban outskirts, or the compulsory acquisition of rural land for a dam, expressway or railway, these are received as inexplicable orders from above. “From the perspective of Langmo villagers, it was state officials who were inscrutable, unsensing interlocutors, their visits seemingly random, their motives opaque or arbitrary. As one elder adamantly insisted to me, ‘They refuse to see with their own eyes.’” [2]

This top-down system of command and control has no room for community consultation, still less for free, prior, informed consent of the governed. Rule by mass mobilisation slogans comes across at village level as predation, for no local benefit, not even gig jobs on construction sites, except for the few Tibetans fluent in Chinese. The disconnect between diktats from above, with realities of community life leave Tibetans increasingly feeling colonised by strong-state power, backed by the coercive presence of the local garrison of PLA soldiers routinely jogging and yelling through the streets, bayonets affixed.

ACCELERATING TENSIONS

Gradually, as Tibetan children learn standard Chinese, their awareness of legal rights, and the unstated logic of China’s infrastructure boom grows apparent. People connect the dots. A few may benefit when the expressways and high speed railways bring Han tourists in their millions to Tibet, but most Tibetans feel they are treated like animals, herded away from rising dam waters and mine sites, to live on urban fringes in resettlement blocks with nothing to do, dependent on official transfer payment handouts from corrupt local officials.[3]

The dangers are multiple and multiplying. Until a few years ago there were spaces in China for alternative civil society voices to query this or that hydro dam. Elite contention linked up with local community advocates, often able to lobby successfully for nation-building projects to be scrapped. Now such voices are silenced by a party-state insistence that its voice is the only public voice. This is an echo chamber. The party-state starts to believe its own propaganda, that all is well in the best of all possible worlds, and the minority nationalities believe in the nation-state. Until they don’t.

These are all issues of concern to security analysts worldwide, who need to be alert to risks, and known unknowns such as those sketched here. This is especially true of China’s far west, Tibet and Xinjiang, which border India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan and Russia, all familiar to strategic analysts as weak points and chronic sources of risk.

China’s unapologetic, openly patriarchal civilising mission drips with derogatory racist stereotypes. In 2017 geostrategic analysts worldwide started to awaken to the consequences, in Xinjiang, but it took a sustained effort, over years by Xinjiang specialists, to persuade the security community to go beyond lazy stereotypes of Uighur “terrorists.” World attention lagged, but then caught up.

Too many security risks have arisen unexpectedly. Some, like a global pandemic, were hard to predict, although security risk analysts were among the few to know it could and probably would happen. Tibet should be recognised as a known known, as a state laboratory for testing and trialling the techniques of grid management, coercive lockdown, big data surveillance and algorithms of predictive policing, all of which were later scaled up in Xinjiang.

Security analysts now need to look much more closely and deeply into Tibet.

[1] Pirie, Fernanda. 2014. The Anthropology of Law. Oxford: OUP. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199696840.001.0001

[2] Charlene Makley, The Battle for Fortune: State-Led Development, Personhood, and Power among Tibetans in China, Cornell, 2018,

[3] Jarmila Ptackova, Making Space for Development: A Study on Resettlement from the Longyangxia Water Reservoir Area of Qinghai Province, Inner Asia , 2016, Vol. 18, No. 1, (2016), pp. 152-166