Blog two of two on the post corona virus new normal in Tibet

Why does China take every opportunity, including the corona crisis opportunity, to erase Tibetan medium schooling, rebuild earthquake devastated towns with fully Chinese characteristics, and use poverty alleviation as a rationale for dislocating Tibetan pastoralists from their land? Why is China so determined to re-engineer all aspects of Tibetan life, land, culture, economy and language?

Many Tibetans would answer this by saying that’s what communist dictatorships do. These days that is all you need say, for people to agree. Across the West, the consensus has shifted just in the past year or two, recognising the many negative consequences worldwide of China’s rise. Now, “communist dictatorship” has become a shorthand explanation, as much as many feel they need to know.

We need to go deeper. China misunderstands Tibet, because it has never listened to Tibetans. In turn, Tibetans should not misunderstand China, and fall back on the clichés of “communist dictatorship.”

Today’s China is not the same as a few years ago. For the security states of the West, it may suffice to stick with “communist dictatorship” as the only explanation required. But Tibetans, who need dialogue with official China, could choose to look more deeply at what drives contemporary China. Is there any other country with such a coercive assimilationist agenda, seizing on disasters to advance its nation building agenda, and further entrench the ruling party as the only legitimate actor, silencing all other voices?

China is unique, and wants to be as unique and exceptional as possible, thus exempt from categories and concepts that long defined the global order that is now disintegrating.

One aspect of what makes China unique is the resurgence of leftish neoMarxists who support a strongly centralised state, with limited scope for private enterprise, because state socialism keeps capitalist excess under control, and the strong state stands up for the nation. It is this combination of nationalism and socialism that has few parallels elsewhere, and is worth understanding in depth.

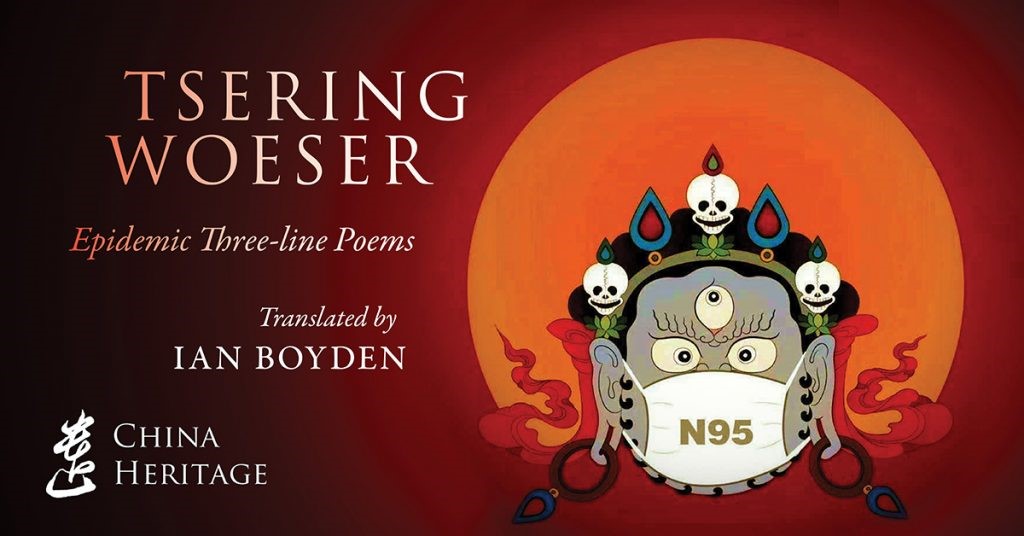

‘The good and bad dying indiscriminately’

Anguished cries everywhere,

we swallow the salt of our overflowing tears

People, no, all living things — how long have you suffered

each in your respective way? How long have you survived

these so-called outbreaks? How much time is left?

Like wild grasses, no, like garlic chives

cut by the curved blades of one plague and another

with unparalleled swiftness, without sound, without rest

The expression ‘garlic chives’, 韭菜 jiǔcài, is a popular term on the Chinese Internet. Because garlic chives [that flavour momos] grow again after being harvested and can be cut down once more, it refers to the weak who are repeatedly exploited and unable to escape. The exploitation of the masses is referred to by employing the visual image of cutting garlic chives. Those that profit from this exploitation are equated with the sickle used to cut the garlic chives. Many people use this metaphor to describe themselves. Of course, we all know who is wielding the sickles. The scythe hangs over the head of every blade of wild grass, over every stalk of garlic chives. It may cut a wild swathe through the field without a moment’s notice.

-three corona virus poems (and commentary) by Tibetan poet Woeser, 2020

Some observers go so far as to see similarities with the national socialism of Europe in the 1920s and 1930s. Both the Italian fascists and German Nazis did consider themselves socialists, greatly concerned with the welfare of the workers. Philosopher Jonathan Wolff reminds us: “Early Italian fascism broke from socialism only on the grounds of nationalism. The Italian dictator Benito Mussolini proposed giving women the vote, lowering the voting age to 18, introducing an eight-hour workday, worker participation in industrial management, heavy progressive capital tax and the partial confiscation of war profits.”

But let’s not push this too far. Trying to make China fit the fascist strong man model is just as much a cliché as calling it a communist dictatorship. Instead, let’s look at what official China and its influencers see as China’s essence. The point is to understand China better, in order to help China understand Tibet better.

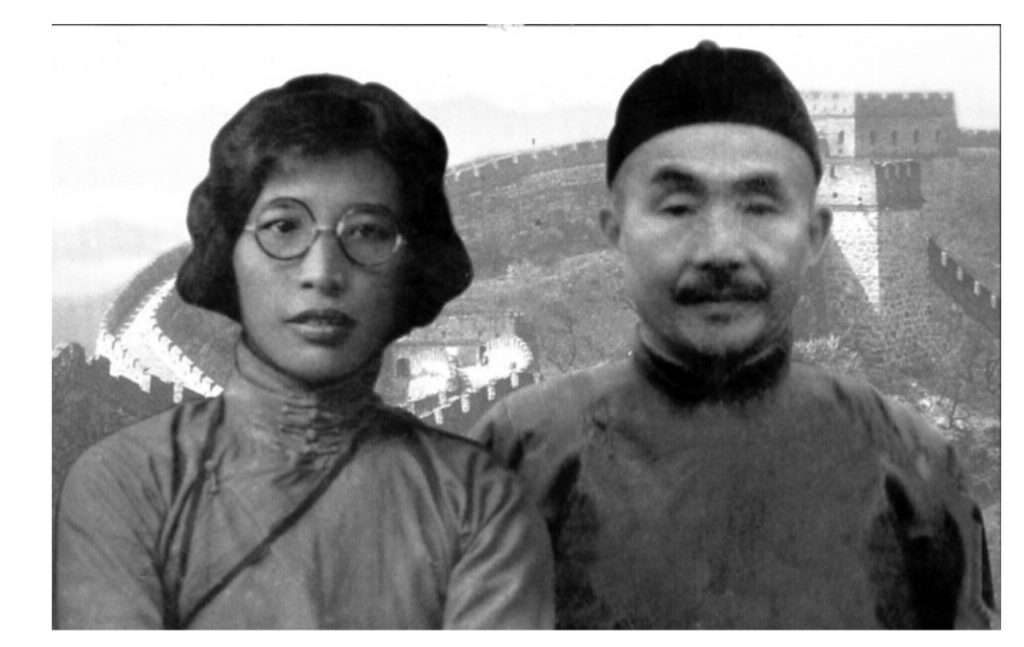

Many Tibetans have tried to this. Back in the 1940s, before communist dictatorship, Lodro Chotso devoted her life to encouraging the Han officials of the Kuomintang regime in power in Kham (Xikang province) to learn who the Tibetans are. This remarkable woman bridged the cultural divide, writing in Chinese, at a time when Han colonisation of Kham meant only predatory tax extraction, not today’s fully assimilationist agenda. Directly addressing the government, she writes: “If one doesn’t understand the feelings of the people and their conditions, one cannot pursue politics. In Kham, 99% of Khampa don’t understand the Chinese language, Han residents make up only 1%, so those officers exert their rule on only 1% of the population, the Han, but they have no relationships at all with 99% of the remaining population, the locals. All my family, starting from my grandparents, to my parents, down to the present generation, has already experienced three or four generations of Han officers’ governance, yet no one has understood what those officers have been doing so far.

“How do Han officers who govern our Kham people live in Kham territory? They cling to the golden rule of ‘using Chinese to transform the barbarians’ (Ch. yong xia bian yi 用夏變夷) as soon as they are appointed officers in frontier regions; they live in Chinese-style palaces built by Han people; they eat rice and vegetables sent to them from inner China; they wear traditional Chinese long robes or trendy Sun Yat-sen-style suits (Ch. zhongshanfu 中山服); everything, absolutely everything they use, has to be brought into Kham from inner China: lanterns, vegetable oil, salt, pickles, vinegar, soy sauce, as well as door inscriptions, candles, artillery and ‘toilet paper to wipe one’s butt’ (Ch. kai pigu de caozhi 揩屁股的草 紙). They, of course, can speak and write only Chinese, they read Chinese books, they publish Chinese-language notifications, they apply Chinese law, they exert Chinese-style coerciveness, they implement the Chinese educational system to build a Chinese land in Kham”. [1]

Now, in this time of aggressive assimilation, it matters more than ever that Tibetans and Han Chinese understand each other.

[1] Lara Maconi, “Mom, Can I Become a Han Officer?” Childhood Memories, Politics, Emancipation and Intimacy in the Chinese-Written Autobiographical Essays of Blo gros chos mtsho, a Khampa Woman (1909/1910–1949) Revue d’Etudes Tibétaines, no. 54, April 2020, pp. 196-240. Free download: http://www.digitalhimalaya.com/collections/journals/ret/index.php?selection=0

LEFTISH ARGUMENTS FOR A STRONG AND PUNITIVE STATE

A strong state 强政府 qiang zhengfu, in official eyes, includes a strongly redistributive state. Redistribution, from the rich to the poor, by the government, is out of fashion in the capitalist West. That is what distinguishes China from purely market economies, in which the state plays a more limited role, deferring to private enterprise, especially the bigger enterprises with the most political influence. For new era China, the state has close relationships with the flourishing private corporations, but there must be no doubt who is in charge. The Party is above all. It is above the law, above the state, and above the narrower focus of the market on wealth accumulation. Socialism with Chinese characteristics.

This unites traditional Confucianists, who have always argued for a strong state, with the resurgent new left intellectual elite, who argue the case for redistribution, achieved by a centralised state strong enough to override local vested interests. It unites nationalists, celebrities, intellectuals and the poor, appealing to anyone who wants China’s success to be exemplary, a beacon the world should admire. It is at the core of China’s claim to be unique, and not to be measured or judged by Western concepts such as universal inborn human rights.

The return of the left, in elite Beijing policy circles, is seldom noticed by Tibetans. Maybe that’s why China’s policy directives are quickly dismissed as just more propaganda.

China’s old left were nostalgic about Mao’s China, and the sense of solidarity and common purpose that persisted until Mao ruined everything. Now there is a new left, who were schooled in Marxism and sometimes inclined to sharply criticise the deep inequality in today’s China. They do favour redistribution to the poor, in part because of their embrace of the strong state.

Professor David Ownby, a close observer of current intellectual elites notes that the influential new left have pushed for the state to maintain its dominance of the economy yet are in “fervent embrace of the power of capital and capitalism, as long as they are tamed by socialism. This is of course not entirely new; there are any number of descriptions of the China model that trumpet China’s achievement of a “third way” that combines the best of the market and the plan. Discussions of the technical means by which China has created this miracle—the key concepts are “top-level planning,” “public capital,” “platform-type local governments,” and “a state based on popular livelihood”.

It is no accident that many of the influential elite thinkers in Beijing who have pushed for the complete abolition of “regional autonomy” for minority nationalities, are of the new left. Wang Shaoguang and Hu Angang are new leftists, contemptuous of religion and tradition, hard heartedly arguing that protests by Tibetans and Uighurs are nothing more than teething pains of modernity, which will pass, once the khenpos and imams have lost their congregations. They argue that a strong state should resist and repress these voices of protest, rather than listen to them.

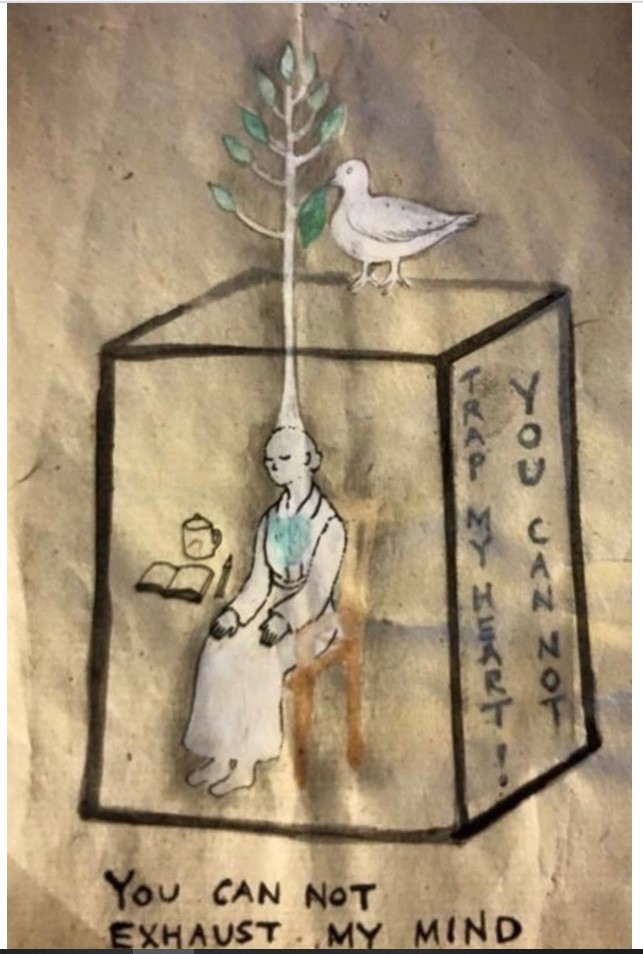

Suddenly, the space in front of the Jokhang is empty

Has there been any time in history that has extinguished in such silence

‘… people have not the slightest fortune or ethics they can trust’

We are all brought under control under one roof

We have lost our voice and our tears

our lives trapped in chaos

Surrounded on all sides by the enemy

it is absurd to describe Tibet as a pure land

in the final analysis ‘the whole country is red’ [Mao]

-three corona virus poems by Woeser

Some prominent new leftists such as Yan Yilong 鄢一龙 begin their case for the strong redistributive state with a critique of capitalism that many Tibetan khenpos, shocked by the intrusion into Tibet of sinful capitalist demons, might well agree with: “One unfortunate consequence of modernity is that capital has replaced everything else, becoming the highest priority. The logic of capitalism pushes everything aside, becoming humanity’s highest rationality. It wipes away the halo of the gods of religion, tears away the veil of family warmth, and destroys the fetters of feudalism so that now ‘there is no nexus between man and man other than naked self-interest, other than callous ‘cash payment.’ Capital has moulded a new culture for humanity, cultivating “public” intellectuals of various stripes, financing all sorts of “neutral” academic research, controlling “public” opinion in the modern media. Capital has reorganized the world order, forcing the Americas, Oceania, Africa and Asia to enter the global system of capital and to submit to the ruling position of the West. The strength of capital is like magic, summoning up from below a bright, beautiful modern world, offering a fake show of peace and prosperity.”

The quotes within our quote are Karl Marx. Yan Yilong presses on: “Without exaggeration, 21st century China’s greatest crisis is that capitalist fundamentalism will take the stage, achieving a position of priority from which to control all other domains. What is the logic of capital? Simply put, it is that money is king. The capitalist market economy is in fact a game of opportunity and equality, but when it’s time to eat, one banquet is set for 85 richest people, while 3.5 billion have to squeeze around the other table.

“China’s wealth gap is also frighteningly large. The data reveal that China’s wealth gap in terms of family property is continuing to grow. In 1995, China’s GINI coefficient for family net worth was 0.45. It was 0.55 in 2002 and 0.73 in 2012. The richest 1% of families possessed 30% of the wealth, and the richest 10% of families somewhere between 63% and 85%. If proper measures aren’t taken to get this under control, China’s polarization between rich and poor will grow increasingly virulent, and political promises of a “shared wealth” will have become pie-in-the-sky empty promises.

Alas! The so-called China Dream is merely something for the losers to revolt against!”

Yan Yilong published this critique in 2016, and has not been punished for it. He is just one of many influential writers arguing that the stronger the market economy grows, the stronger the state must be to keep it in check. “In today’s China, the reason that the strength of capital is still unable to control politics and dictate policy is that it is still not the strongest force in the country. But if China develops a system with a tripartite division of powers, as many are strongly advocating, a multi-party regime with competitive elections, then the greatest recipient of the benefit of the division of power will be capital, after which capital will bend political power to its will and deprive the people of democracy. Socialist ideology is the theoretical weapon of the labouring masses, and the base on which is relies for its long-term development is the strength of morality and justice. By way of contrast, capitalist ideology employs the strength of capital to penetrate every corner of society, becoming omnipresent. China is at present facing a huge ideological crisis. The cultural system has been largely marketized, with monopoly capital controlling all new media, the Western system of humanities and social sciences is spreading its message unchanged, and some scholars have come to believe that it is natural to “speak for the wealthy.”

Far from being censored and silenced, much of this critique, with its cult of state power as the supreme necessity of these times, finds favour in new era China. It provides fresh legitimacy for the state, as long as it redistributes.

THE STRONG STATE COMMANDS ALL UNDER HEAVEN

Yan Yilong reaches his punch line: “Without the help of capital’s strength, socialism cannot succeed; but without socialist constraints, capitalism becomes a raging flood, a wild beast. Capital truly is a steady horse that propels society forward, but this horse must wear the blinders of the “public interest” in order to better serve the interests of all of the people. In the process of a new round of reform of the state economy, socialist elements have not retreated, but have been strengthened through the power of their control of capital.”

Is this just an ingenious rationale for CCP power? Or the arguments of an irrelevant intellectual? It is more elegant than the official slogan “党政军民学,东南西北中,党是领导 一 切的 , government, military, society, education, north, south, east, west — the party leads everything.” Yan Yilong’s views are distinctive, but more broadly the new left is now influential, and new era China has indeed decisively turned away from the state retreating, while capital advances. State owned enterprises are stronger than ever, despite the urgings of American investors and the neoliberal consensus. As Yan Yilong says: “The state economy controls the lifeblood of the national economy, like a national economic army that comes when it’s called and wins when it arrives. Globally, it is the main force promoting the achievements of the state’s strategic objectives, but in times of crisis it is also the major force in meeting the crisis. This is because a state-owned enterprise is not only an economic animal, but instead assumes its social responsibilities, and in times of need, can sacrifice the interests of the enterprise to those of the people and the society.”

Effective poverty alleviation fits in with this ideological package, and may explain the determination of the State Council to help the remote poor to raise their incomes.

The need for a strong state gets a lot of support by Chinese thinkers who, since the start of this century, have seen the liberalism of the West as stumbling and failing, not as a model China should follow. Instead the anti-liberal ideas of Carl Schmitt are popular in China, arguing for the supremacy of politics above all, for the strongest of states, and for a state that is fixated on its enemies. “Classical liberalism assumes the autonomy of self-sufficient individuals and treats conflict as a function of faulty social and institutional arrangements; rearrange those arrangements, and peace, prosperity, learning, and refinement will follow. Schmitt assumed the priority of conflict: Man is a political creature, in the sense that his most defining characteristic is the ability to distinguish friend and adversary. Classical liberalism sees society as having multiple, semiautonomous spheres; Schmitt asserted the priority of the social whole (his ideal was the medieval Catholic Church) and considered the autonomy of the economy, say, or culture or religion, as a dangerous fiction. “The political is the total, and as a result we know that any decision about whether something is unpolitical is always a political decision.” Classical liberalism treats sovereignty as a kind of coin that individuals are given by nature and which they cash in as they build legitimate political institutions for themselves; Schmitt saw sovereignty as the result of an arbitrary self-founding act by a leader, a party, a class, or a nation that simply declares“thus it shall be.’’[1]

The cult of the state attracts so many in China. In 2020 in Chinese eyes, the liberalism of the West seems, more than ever weak, ineffective, conflicted, ineffective; while the new era proclaimed by the CCP is assertive, decisive, capable and successful.

INCOMPREHENSIBLE DISCOURSES OF THE CENTRAL STATE

Tibetans have endless experience of the strong state intruding into private lives, usually punitively and with extreme prejudice. The strong state takes every opportunity to advance and assert its dominance, whether by sidelining the Tibetan mother tongue in Amdo Ngawa schools, or the reconstruction of Yushu, or new instructions on how to do poverty alleviation. The new system of national parks across the Tibetan Plateau follows the same logic of the state projecting its power into remote landscapes it had little interest in until recently.

Tibetans experience most of these extensions of the state’s reach as unwelcome, and often resist. It is hard to imagine hundreds, perhaps thousands, of trained and qualified Tibetan teachers, suddenly redundant, not protesting vigorously. Elsewhere in Tibet, such mother tongue protests have succeeded. Many eloquent refutations of China’s assimilationist education agenda have been written by Tibetans.

THE STRONG STATE AND ITS ENEMIES

A difficulty many Tibetans experience is that the initiatives and intrusions of the central party-state seem arbitrary, ill-considered, pointless or counter-productive, unpredictable, unreadable and senseless. Yet, for central leaders, all these policy pushes share a coherent, common nature. They all push Tibet towards modernity, urbanisation, wealth accumulation, scientific land management, access to science and career prospects through learning putonghua, a post-agricultural and post-industrial future in cities, perhaps as commodity chain distributors of Tibetan wool and dairy at last entering China’s huge market on more equal terms of trade. This is the modernity package.

Seeing China’s many new policies in Tibet through the eyes of China’s ascendant new left statist elite doesn’t make them acceptable, on the ground, in Tibet, but at least it makes them comprehensible. And that means readying for the passing of the corona virus crisis, leaving the state more firmly in power than before. Seeing how Tibet looks, through elite eyes in Beijing, makes it easier to anticipate further statist nation-building policy shifts.

The cult of the state unites people across the spectrum in China, from Confucian traditionalists to new left Marxists who want the state to curb the greed and selfishness of capitalism. Their fascination with the Nazi legal theorist Carl Schmitt reminds us the sovereign state not only finds its enemies and attacks them, it needs enemies, in order to define itself. It is the fate of the stubborn Tibetans to be the eternal enemy, for refusing to become Chinese. ”Not only is there a wide range of people that the Party-state considers deserve to be placed outside of society, but also in contemporary China detention is still considered to be a very useful form of social management and control.”[2] The punitiveness of the strong state, in Tibet and Xinjiang, is not incidental; it is of the essence of the strong state with Chinese characteristics.

The popularity of Carl Schmitt gives us an insight into the attractions of a strong and punitive state: “The friend-enemy distinction encourages a stark form of binary thinking. The category of friend, however substantively defined, can be conceived only by projecting its opposite. ‘Friend’ acquires meaning through knowing what ‘enemy’ means. The attributes used to define a ‘friend’ can, as Schmitt pointed out, be drawn from diverse sources. Religion, language, ethnicity, culture, social status, ideology, gender or indeed anything else can serve as the defining element of a given friend-enemy distinction.

“The friend-enemy distinction is a public distinction: it refers to friendship and enmity between groups rather than between individuals. (Private admiration for a member of a hostile group is always possible). The markers of identity, however, are relatively fluid because a political community is formed via the common identification of a perceived threat. In other words, it is through singling out ‘outsiders’ that the community becomes meaningful as an ‘in-group’. This Schmittian way of defining a ‘people’ elides the necessity of a legal framework. A ‘people’, as a political community in the Schmittian sense, is primarily concerned about whether a different political community (or individuals capable of being formed into a community) poses a threat to their way of life.”

In many ways this is new. As recently as the first years of this century, Tibet remained over the horizon, too far from central leaders to care much about, unless it appeared to threaten national stability. Tibet was the frontier, or in practice beyond the frontier, to be exploited, but not actually governed, except for the enclaves of modernity with Chinese characteristics, in the municipalities and the logistic networks connecting them to lowland China. The vastness of the Tibetan Plateau for decades remained an unknown hinterland, combed by heroic geologists for mineral deposits and engineers for hydro dam sites, but otherwise a terra incognita. For decades, swarms of predatory gold miners and ruthless wildlife hunters roamed Tibet, and central leaders took no interest.

But now China projects its power into all Tibetan landscapes, zoning them all as either ecological or economic, the two categories being mutually exclusive. The unfinished business of making an empire into a nation is back on the agenda.

MODERNITY WITHOUT DEVELOPMENT

The core paradox is that China takes every opportunity to impose modernity but without development. Almost anywhere, development and modernity are closely intertwined; economic progress, a new division of labour and new urbanisation. In Tibet especially the nation-building state seizes the opportunity of an earthquake, or a viral pandemic to advance its agenda of urbanisation, rural depopulation and urban concentration under surveillance. Yet Tibet remains under developed, under invested except in the enclaves, under linked, unintegrated, unable to access the win-wins central leaders love to talk about.

This is a paradox, as the rebuild of Yushu city cost $7 billion, and in addition a new expressway greatly reducing the time taken on the 700 km journey between Yushu and provincial capital Xining, added billions more.

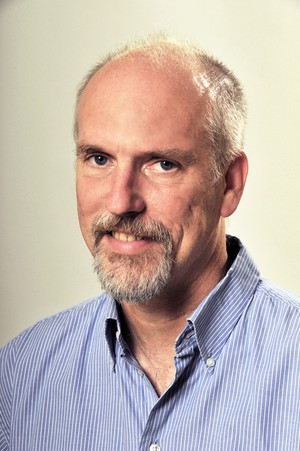

Development economist Andrew Fischer, in a lengthy analysis, says: “the development discourse of the CPC with regard to Tibet treats the particular mode of integration of the Tibetan areas into the national economy through the implementation of western development strategies as if there is no alternative. This mode of integration that has dominated since the late 1980s has essentially accentuated the disempowering and assimilationist dynamics of development, even while providing for strong economic growth and the rapid build-up of certain types of infrastructure, that is, those conceived principally within a broader centre-periphery relationship.”[3]

Modernity with Chinese characteristics but without development means Tibetan remain poor and marginal, whether still on ancestral rangelands or in cities. It means dependence[4] on official rations and handouts, for which Tibetans are required to publicly express gratitude. It means, most recently, Han immigrants arriving in Lhasa, excitedly explaining they are from Wuhan, while Tibetans remain in chronic lockdown, under tight surveillance, movement restricted.

For a few weeks the whole of Hubei, then the whole of China, experienced the restrictions Tibetans, especially in Lhasa, have long lived under. Tibet is where China’s grid management lockdowns were trialled, tested, tweaked and institutionalised. The phone apps that tell the security state where you are, at any time, were first developed to track Tibetans, later to track those exposed to corona virus infection.

The virus contagion allowed the security state to advance, in a great leap forward. It is the same security state that is obsessed with Tibetans as an infectious threat to stability, and with viruses as threats to stability. When the virus arrives, the security state advances; when the virus fades, the security state advances: ask the unemployed Tibetan teachers of Ngawa prefecture.

Why has Carl Schmitt enjoyed such an afterlife in China? Not only does he argue eloquently for a strong state, and for the primacy of politics above all else, he also argues that the state is constituted by its enemies.

The need for enemies is not an accidental outcome of in-group solidarity, an unwitting dualism that fails to recognise that, as the lamas often remind us, all concepts entail their opposite. Cold is meaningless unless there is also a concept of hot. Us remains vague until set in opposition to them.

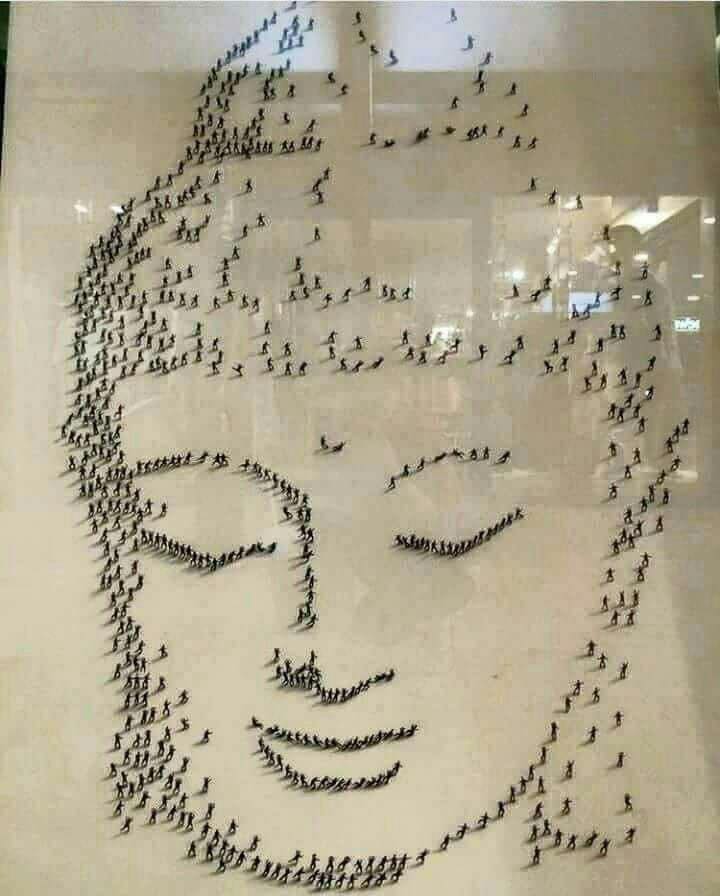

The Chinese Communist Party, gearing up to celebrate its centenary in 2021, has always been obsessed with the hunt for enemies, both internal and external. Under Mao, the number of class enemies plotting to wreck the revolution was a fixed proportion, usually five percent. Never more and seldom less. This ratio of one in twenty enabled the majority to feel secure that they were actually a supermajority of likeminded folks, all that is needful is to weed out the one from the 20.

The class traitors, bourgeoisie and stinking intellectuals to be purged never seemed to drop much below five percent, a plague that is always with us, requiring eternal vigilance.

In order to maintain the friend/enemy polarity, identifying the enemy is of paramount importance. But, having named the enemy, it is equally important to know as little as possible about them, lest they become human, rather like us. This happens over and over. If you know too much about your enemies, you might recognise a mirror image of yourself. In the Cold War, Sovietology was a considerable industry in the US, and almost no-one foresaw the collapse of the Soviet bloc. Instead the Sovietologists routinely over-estimated the strengths and durability of the Soviet Second World. That is just one example.

The nomads of the north, as the eternal enemy of China, goes all the way back to the imperial court historian Ssu-ma Ch’ien (Sima Qian), who “gives to the history of the northern frontier independent status as an object of investigation, but at the same time it places the north in a position whose only referent is China: the history of the nomads came into existence, as it were, because it was relevant to China. This polarity has within itself the power to generate a false causal relationship, namely, that not only Ssu-ma Ch’ien’s narrative, but also very the history of the Hsiung-nu, and perhaps of the nomads, came into existence as a product of the timeless frontier relationship between nomads and China.” [5]The unending enmity between civilised China and the nomadic barbarians of the north is from the outset a Sinocentric confection.

In Ssu-ma Chi’en’s time, 2nd century BC, the pastoralists could be defined as external enemies. But between the late 13th and early 20th centuries, those northern barbarians, first the Mongols and later the Manchu, not only conquered China but ruled for many centuries, actually for most of the whole period from 1279 to 1911. This has resulted in convoluted rationalisations by subsequent court historians and later the CCP. On one hand, they want to claim 5000 years of unbroken history, China’s foundational claim to uniqueness. This requires the claim that the conquerors quickly became Chinese, thus maintaining China’s cultural continuity. On the other hand, the hated Manchu Qing were overthrown in 1911 by popular hatred, and hatred towards the inside/outside enemies in the grasslands has persisted ever since. The current solution is coercive assimilation, especially in Xinjiang and Tibet.

Are the Tibetans among China’s eternal enemies? Despite being insider/outsiders the Tibetans have never come sufficiently far inside to be considered cooked, the classic Han metaphor for assimilation. The Tibetans remain raw and ungrateful.

New era China remains imprisoned by its past court historians.When it comes to clearly external enemies, such as the US,the ambivalence is even more intense. The beautiful country, meiguo, is above all to be admired, emulated, imitated. It has long been where the party-state elite send their children to college. Yet the beautiful country, especially at present, is also the enemy, the biggest of enemies, the hegemon patrolling China’s seas, opposing China’s rise, sabotaging China’s plans.

China’s resurgent nationalism is reinforced by the existence of the enemy, and by the creation of ever more enemies onscreen, so China’s “wolf warriors” can enjoy the thrill of cheering on their heroes as they beat evil Americans to pulp, or single handedly defeat an invasion from outer space. These are the most popular movies made in China, highly profitable, even if they seldom resonate with nonChinese audiences.

This scaled up tribalism makes it easy for Han Chinese to dismiss Tibetan voices, as nothing more than the squawks of peripheral barbarians who don’t know what is good for them, who are to be modernised, harmonised, assimilated and merged into the great Chinese race, whether they want to or not. It takes only a moment for Han to recall that China is on the rise, and no backward tribe on the margins need be taken seriously.

Does this hegemonic master narrative mean Tibetans are helpless? Not at all. Tibetans have, again and again, resisted coercive assimilation by maintaining identity and solidarity, despite the pressure. That’s the short term response, and it often works. After all, does China really want mass unemployment among Tibetan schoolteachers made redundant by the switch to Putonghua? In a land where teachers are still respected, and the teaching profession is as high as Tibetans can aspire to, a sudden loss of career path for educated Tibetans is also a worry for the security state.

I hadn’t read the Vajra Armor Mantra before

Now, I’m on my ninth day of reading it 108 times a day

My reading more and more fluent, my heart more and more reliant on it

If we see the virus as a ‘strange moon’, then will we not also see a strange world? The clear cold moonlight illuminating the dark of night also illuminates life itself. Under that light we can readily perceive the impermanence of all things. This is a good thing. However, my Buddhist practice leads me to believe that our present incarnation is just a single lifetime, one of many lifetimes that are bound together.

-corona virus poem and commentary by Tibetan Buddhist poet Woeser

In the long term, the best prospect for Tibet is to persist, come what may, with reminding any Han Chinese who listens, that Tibetans are their better selves, that Tibetan Buddhism is the key to happiness, whether one is rich or poor. This has been the Dalai Lama’s aim for many decades, likewise the many charismatic lamas and khenpos who have dissolved friend/enemy dualisms and taught the Han flocking to them how to take better care of the mind and its discontents.

In the long run this will be effective. Han Chinese who learn to listen to lamas who introduce them to the nature of their own minds also learn to listen to Tibetans on other subjects, and to make the surprising discovery that Tibetans generally have a good approach to the challenges of life. Learning to listen and appreciate Tibetans brackets the sloganistic, repetitious official message, exposes its vacuousness and irrelevance to reality.

At a time when a racist party-state locks a million or more Uighurs in compulsory rote-learning slogan chanting, is there any time left? Many Tibetans, finding the mandatory repetition of official slogans to be suffocating, will worry whether a long term strategy of awakening openness can work soon enough to be effective.

Yet Tibet and Xinjiang are not the same. Revolutionary China called Buddhism a foreign religion, as it does to Christianity today, to be repressed and expelled simply for its foreignness. Official China ceased calling Buddhism, including Tibetan Buddhism foreign, decades ago. Xi Jinping calls on Buddhism as a social force that helps combat endemic corruption. That is progress.

There are just too many Han Chinese who have discovered the Buddhism of their grandparents was more than offering incense to a statue in a temple, that Buddhist practice can be radically transformative. Millions of Han have discovered that the Buddhism of Tibet best maintains continuity of insight and awakening, best exemplifying -in exemplary lives- how to live authentically and happily, whatever the circumstances.

Dawa Norbu reminds us, in his China’s Tibet Policy: “Buddhism, whose penetration and diffusion in China predates the Yuan dynasty, has tended to soften, if not diffuse, the authority and power relations between the Middle Kingdom and Buddhist dependencies. This was particularly true of Tibet, which since the twelfth century was progressively projected and perceived as the Vatican of Mahayana Buddhism. We find no parallels in Chinese history to the highest-level state receptions accorded to the Vth Dalai Lama by the Qing Emperor, to the Sakya Lama (Phagpa) by the Yuan Emperor and to the Vth Karmapa Lama (Dezhin Shakpa) by the Ming Emperor. None of these Tibetan Lamas had to kowtow before the emperor; kowtow culture was transformed into mutual respect.“

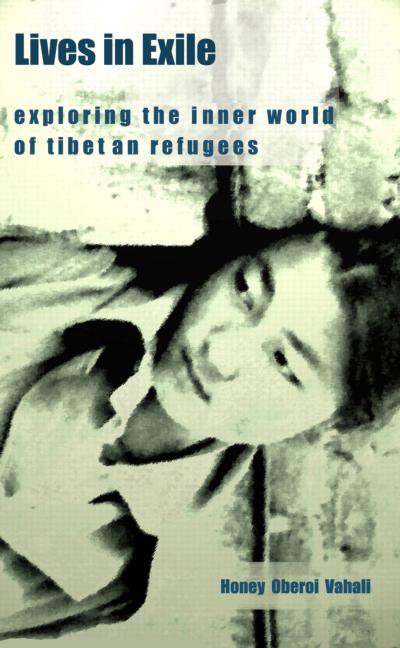

Awakened Tibetans have been turning minds for a long time, sometimes over years, in the intimacy of a teacher-student transmission, sometimes momentarily in a spontaneous gesture towards a stranger. Honey Oberoi Vahali, a psychoanalyst, tells of such a moment when she was six, a child on holiday in Shimla with her family, discovering in a humble market stall of a Tibetan woman refugee a red coral ring:

“The shop was owned by an elderly Tibetan woman with two long plaits, dressed in a chuba. My eyes must have shone with wonder and amazement. The Tibetan lady smiled at me. I smiled back. Then a few minutes later I began urging my mother to buy me the ring. Even as my mother considered my demand, the smiling Tibetan lady emerged from a small trapdoor in the shop and came forward with the ‘precious’ ring in her outstretched hand. Straightening herself, she slipped the ring on my second finger. As my mother was opening her purse to pay her, the lady patted me affectionately on the head, pecked me on the cheek and told my mother, ‘Let the little one have it as a gift from me.’”

From that came Honey Oberoi Vahali’s decades of immersion in Tibetan refugee lives, a sensitive and insightful book on the lives of Tibetans in India, psychotherapeutic work among torture survivors, and an ongoing voice for refugees everywhere.

Honey Oberoi Vahali tells us during partition her folks fled what is now Pakistani Punjab so, even as a child, she understood what it means to be a refugee. My mother too was a refugee, from Hitler’s advances across central Europe, and I grew up in Australia in a family that wanted to be as far from Europe as possible.

By being themselves, acting not instrumentally but spontaneously, Tibetans turn minds. May it ever be so.

As editor of Rukor, I too had a moment which turned my mind. As a journalist and radio documentary producer, I interviewed Gyalwa Rinpoche back in 1977, then toured several Tibetan settlements, recording more interviews, which eventually became a lengthy radio series broadcast in Australia, Paths to Shangri-la.

After that initial interview in Bodhgaya and months on the road I finally came to Dharamsala and was invited by Westerner friends to join a group audience with Gyalwa Rinpoche. With so many cassette tapes in hand, I had no intention of asking His Holiness anything, my plan was to just sit quietly at the back.

To my astonishment, he turned to me: “You! You have seen how we Tibetans live. Do you have any suggestions?”

Journalists are trained to quickly sum up any situation and reduce it to words, a reason why so much reportage is cliched. It would be so easy to say, without any responsibility, why don’t you do this, or that?

My mouth was already open. In that moment I decided that anything I did say I would also accept some responsibility for. I said: “Your Holiness, there are things that could be done, and I will do what I can to help.” Like that red coral ring, this has stayed with me for over 40 years. The turning of the mind was a specific moment. Rukor has come from it.

Gabriel Lafitte

When I read this haiku I started to cry:

‘In the wind, I loudly pray: Namo Guanshiyin Pusa’

Please release the souls, lost, packed into the bardo …

I think that everyone who is struggling with the plague are in a kind of bardo, one that we need to free ourselves from. But in my poem I also call the thousands of departed souls who died as a result of the plague ‘wanderers’. They didn’t want to die; surely they still long for the realm of the living and so they linger in the murky limbo of the bardo. It is a harrowing and sorrowful state. I pray, as a Buddhist, for all of those lost souls and for their rebirth. As I am still in the realm of the living it is something I felt that I could do, and so I have.

The descriptions of hell in Buddhist sutras are very detailed, although people don’t usually think of them as being literal. To my mind, however, presently we are living in all six realms of samsara and circulating through the eighteen levels of hell. It is something that is happening right now. It is not a metaphor.

I encountered Taneda’s haiku during the outbreak of the epidemic. I learned that he was a mendicant monk who travelled by foot, a monk who wandered through the clouds. His haiku is suffused with the ‘voice of the dharma’, and its language is beautiful. I read about how he felt he was walking with Buddhas and Bodhisattvas. Walking on the road. Walking in the wind. Walking and praying. To him prayer is as routine as chatting.

I love the feeling of the wind. I think the wind that blows from snow-shrouded Everest towards lowland China is a true wind without impurities, it carries the smell of my homeland, Tibet. When I stood in that wind and chanted ‘I take refuge in the Bodhisattva Who Perceives the World’s Cries’ [南無觀音菩薩], I experienced a profound sense of consolation. As a result, I was not so anxious, not so fearful of the political plague.

I like the resonances of the original Japanese haiku even more. The way this voice floats in the wind, how this voice attaches to the wind, how it leaves its traces on the wind. This voice is a prayer in all languages be it Japanese, Chinese, Tibetan, English, or whatever.

-Tibetan Buddhist poet Woeser’s response to corona virus, in poetry and prose commentary

[1] Mark Lilla, Reading Strauss in Beijing: China’s strange taste in Western philosophers. New Republic, 30 December 2010

[2] Sarah Biddulph, Elisa Nesossi, Susan Trevaskes and Flora Sapio, Detention and Its Reforms in the PRC, China law and society review 2 (2017) 1-62

[3] Andrew M Fischer, Disempowered Development of Tibet in China, Lexington, 2013, ch 4

[4] Andrew M. Fischer, The Revenge of Fiscal Maoism in China’s Tibet, Erasmus Working Paper No. 547, July 2012

[5] Nicola di Cosmo, Ancient China and its Enemies, Cambridge, 2002, 316