FORGING THE CHAGLAM IRON PATH ACROSS EASTERN TIBET

First of two blogs

In 2006, when the single track rail line across the permafrost of northern Tibet to Lhasa began operation, China congratulated itself, long and loud, for its engineering accomplishment.

The sky train across the roof of the world was a world first, the highest altitude train line in the world. The propaganda machine in overdrive declared China could conquer all natural obstacles, having gained mastery over the glacial peaks and the vast, empty northern plan –the Changtang- traversed by the new line, plied by 361 specially designed carriages built by Canada’s Bombardier.

In the decade since then, the trains have arrived daily, from Beijing, Shanghai, Chengdu and other major cities, bringing the bulk of the millions of domestic tourists on package tours of “China’s Tibet”, herded from one state-owned scenic site to the next by accredited tour guides on script about each iconic photo opp. Then they go back, on the same air-conditioned, pressurised train, taking 48 hours to return to Beijing or Shanghai.

Little else takes this route from Lanzhou, via Xining and Gormo to Lhasa; as there is limited freight traffic in (most goes by road) and almost nothing leaves Tibet, since China has failed to develop Tibet’s pastoral economy, and the copper mines to both west and east of Lhasa have largely failed to scale up to significant operations.

Since 2006, China has continued to invest mightily in rail, especially in high-speed routes, both north-south and east-west, creating deep linkages and economic stimulus with Chinese developmentalist state characteristics. China understandably is proud of these accomplishments, even if they are achieved by borrowing heavily from future generations to finance staggering capital expenditures.

But none of the recently constructed rail lines have been celebrated as much as the opening of the Lhasa line. Even high speed lines are now so many that they have become routine. The inauguration of a high speed line across the northernmost mountains of the Tibetan Plateau attracted little attention.

However, China has now announced, as part of the 13th Five-Year Plan to 2020 that it will fund and proceed with a highly ambitious rail line from Chengdu, capital of Sichuan province, to Lhasa via Nyingtri. This rail line, tunnelling and bridging its way through precipitous Kham, or eastern Tibet, and deep into central Tibet could take as much as three successive Five-Year Plans to build. For engineers, this is a greater challenge than the existing line across the alpine deserts of the Changtang. Xinhua announced that: “the new railway will be about 1,629 km long, and it will only take 15 hours for trains traveling between Lhasa and Chengdu.” [1] The route is slightly shorter than the northern Tibetan desert route, and trains will average 108 kmh.

The total budget is not available, but a budget for the first section to be constructed, from Lhasa to Nyingtri, was announced in late 2014 as RMB 36.6bn ($US 6bn) and construction is due to be completed by 2021. From an engineering perspective, this section is far less challenging, largely able to follow river valleys and plateau contours, than the line from Nyingtri across Kham.

FROM INLAND CHINA HIGH SPEED TO XINJIANG VIA TIBET

If we are to understand the impacts and obstacles of the Chengdu-Nyingtri-Lhasa route, we could start by taking a closer look at the new high speed line across far northern Tibet, the new fast route connecting eastern China via Lanzhou with Xinjiang and the Eurasia overland route to Europe.

Historically, the Tibetan Plateau has not been a shortcut to anywhere. The silk route traders skirted Tibet. China’s current plans for international rail networks focus on the “one belt, one road” route through central Asia, and on a grand plan to connect to India, Myanmar and Southeast Asia, via Yunnan, creating another grand architecture of trade by rail, for China’s future prosperity and access to raw materials. The first route skirts Tibet, to the north, the latter skirts the southern flanks of Tibet, which remains a vast island in the sky, entire unto itself.

Historically, the Tibetan Plateau has not been a shortcut to anywhere. The silk route traders skirted Tibet. China’s current plans for international rail networks focus on the “one belt, one road” route through central Asia, and on a grand plan to connect to India, Myanmar and Southeast Asia, via Yunnan, creating another grand architecture of trade by rail, for China’s future prosperity and access to raw materials. The first route skirts Tibet, to the north, the latter skirts the southern flanks of Tibet, which remains a vast island in the sky, entire unto itself.

But if we look more closely at the new high speed route to Urumqi, the capital of Xinjiang, we learn what China rail has achieved in the past decade, what its capabilities are now, and how ready it is to tackle the deep gorges and high peaks en route from Chengdu to Lhasa.

In 2013 The Economist reported on this new rail line: “The new high-speed railway line to Urumqi climbs hundreds of metres onto the Tibetan plateau before slicing past the valley where the Dalai Lama was born. It climbs to oxygen-starved altitudes and then descends to the edge of the Gobi desert for a final sprint of several hundred windblown kilometres across a Martian landscape. The line will reach higher than any other bullet-train track in the world and extend what is already by far the world’s longest high-speed rail network by nearly one-fifth compared with its current length. The challenge will be explaining why this particular stretch is necessary.”[2]

The route to Xinjiang is beset by technical challenges, especially extremes of weather, including gales so strong they can threaten to blow trains off track. However Bombardier’s Chinese partner, Sifang, has overcome these problems, and even sent its new design carriages to Vienna to be tested in a wind tunnel, the ultimate seal of approval. Little wonder, then, that International Rail Journal marvels at the new high speed line in Xinjiang: “The 1776km high-speed line from Lanzhou to Urumqi in the Xinjiang region of northwest China must rank alongside the Qinghai Tibet Railway as one China’s greatest engineering achievements of recent years. The 31-station line crosses the Gobi desert and the Qilian Mountains [Chokle Namgyal in Tibetan], reaching a summit of 3607m above sea level in the Qilianshan No 2 Tunnel, making it the world’s highest high-speed line.

“This is an environment defined by extremes, from high desert winds and sandstorms to intense ultraviolet radiation and heavy snowfall. Ensuring rolling stock could meet the demands of operating safely and reliably at speeds of up to 250km/h was one of the key engineering challenges of this remarkable railway, and CRRC Corporation has spent three years developing a high-speed train specifically for operation in this high-altitude environment.

“The 250km/h trains are being supplied to China Railway Corporation (CRC) by CRRC’s Qingdao Sifang subsidiary and are designed to operate in temperatures ranging from -40 to +40oC as well as sandstorms, high-winds, and intense ultraviolet light. Bogies have been adapted to prevent frost, snow, and ice accumulation while the sealed body shell reduces the risk of failures caused by condensing meltwater. Underfloor equipment cabinets are pressure-sealed to minimise sand and dust ingress and a sediment control ventilation system ensures on-board air quality is maintained. An anti-roll device ensures lateral stability in strong winds. Electrical equipment has been configured to minimise the risk of damage from lightning strikes, and traction motors, converters, and transformers have been configured for operation in low ambient temperatures.”

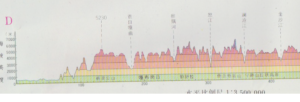

Many of these technical adaptations to extreme weather are relevant to the line to Lhasa via Nyingtri, due to start construction soon. In Kham, the winds are not as fierce, but the terrain is far more difficult, as is evident in this transect cross-section of the Tibetan Plateau, starting (on the right) in the lowland Sichuan, reaching Nyingtri at 4300 metres.

Many of these technical adaptations to extreme weather are relevant to the line to Lhasa via Nyingtri, due to start construction soon. In Kham, the winds are not as fierce, but the terrain is far more difficult, as is evident in this transect cross-section of the Tibetan Plateau, starting (on the right) in the lowland Sichuan, reaching Nyingtri at 4300 metres.

WHY BUILD IT?

In democracies, railway projects, especially ambitious long distance projects, have to justify their huge capital expenditure, alongside alternative uses for the same capital. To justify going ahead, proponents of a major rail construction have to produce a business case that, at the very least, shows the likely economic benefit outweighs the cost of construction. In global development finance, when the development banks choose to finance a major project, there is a similar requirement that both before a project is approved, and again after its completion, the economic and social benefits are quantified, as against alternatives.

For example, when the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and the French government’s aid agency contemplated joining the Chinese government in financing a rail line through rugged northwest Yunnan, from Dali to Lijiang, many studies and reports were done to make the case for the project which was expected to cost $548 million and ended up at over $800 million for a rail line only 167 kms long. On the ADB website many downloadable documents enable anyone to access the rationale for this project, before, during and after its construction. The ADB’s “Validation Report” of 2015 calls the project a success for reasons that could apply equally to the Chengdu-Nyingtri-Lhasa railway: “due to inadequate transport, the largely mountainous project area had not been integrated into the economic mainstream. The then existing class II roads had to pass through difficult terrains, had limited passing capacity, and were affected by rain. Despite abundant natural resources, many people in the area were poor, with most working in the agriculture sector. In the mountainous areas, people supplement their incomes by engaging in animal husbandry or becoming migrant labourers.”[3]

The railway now connects these poor mountain folk not only to Kunming, the capital of Yunnan, but to high speed rail links right across China: “The railway link was to allow connectivity from northwestern Yunnan province to Kunming, Shanghai, and Beijing via three of the 16 east–west and north–south national rail Corridors. The project and associated developments could stimulate industrial and natural resource development, tourism, and related industries; generate employment; increase living standards; and help reduce poverty.” The business case, made in 2004, was quite specific about how success was to be quantified: “The project’s expected outcome was the development of an efficient, reliable, and affordable railway transport system to improve access and reduce transport costs in the project area. The identified performance indicators were (i) a project economic internal rate of return (EIRR) of 17.0%, (ii) increased railway freight traffic from 5.4 million tons in 2010 to 7.2 million tons by 2015, (iii) increased railway passenger traffic from 3.1 million passengers in 2010 to 4.4 million passengers in 2015.”

Most of these targets were not fulfilled. After the rail line was built in 2009, the number of passengers two years later was only one third the projected number, rail freight was minimal, the rate of return on capital deployed was far lower than expected, yet ADB (as expected) declared itself generally satisfied.

Most of these targets were not fulfilled. After the rail line was built in 2009, the number of passengers two years later was only one third the projected number, rail freight was minimal, the rate of return on capital deployed was far lower than expected, yet ADB (as expected) declared itself generally satisfied.

No such process exists for the Chengdu-Nyingtri-Lhasa railway, since it is a project of the 13th Five-Year Plan, financed entirely by China, and makes no business case, still less a publicly available one.

MILITARY USES

The case for proceeding is less a business case, and more to do with accomplishing other goals of China’s central leaders. A high priority is Beijing’s long standing preoccupation with security and stability, especially the 2015 decision to no longer divide the Tibetan Plateau into the Lanzhou Military Region covering northern Tibet, and the Chengdu Military Region covering southern Tibet, both Kham and the U-Tsang province of central Tibet including Lhasa. The locus of military command in Chengdu has long been an embarrassment, as the only way of projecting military power out of Chengdu, up into eastern and central Tibet has been via the two highways, chronically prone to monsoon-triggered landslides, earthquakes and other extreme weather events. In case of an emergency on China’s borders, or another uprising of the Tibetans, if local garrisons of PLA troops and PAP paramilitary prove inadequate, the logistical supply line from Chengdu is long and unreliable.

Nyingtri is only 50kms from the Indian border, a border China does not recognise, instead routinely mapping the neighbouring Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh as “southern Tibet” on all official maps of Tibet.

Now that the Lanzhou and Chengdu Military Regions have been abolished, and replaced by a single Western Theatre Command (modelled on US lines), it has become essential that China can speedily move military assets into troubled areas, not only in Tibet but also Xinjiang, to supplement existing ground forces already in station. The Chengdu-Nyingtri-Lhasa rail line is essential, and needs to make no business case, as the military case is compelling.

The absence of a business case, made against competing claims for investment, does not trouble China’s central planners at a time when China persists in massive stimulatory expenditures financed by increasing debt. The long term sustainability of ever-increasing debt worries many observers, including Dr Wang Tao, of UBS. She writes: “The fact that debt is rising much faster than output and an increasing share of debt is allocated in non-productive or excess capacity sectors means resources may have been wasted and more potential bad debt are being created.” At present, China’s central leaders give highest priority to stimulating growth, and investment in big-ticket railway construction has long been a favourite. But the Chengdu to Lhasa rail project could take as long as three consecutive Five-Year Plan periods to complete, with many shifts in priorities and capabilities along the way. It is quite possible that in coming years this project will be seen as the expensive construction of non-productive assets, at a cost of alarmingly high debt levels to be paid by future generations. The project may need to be re-evaluated, and make a business case, even if such information is not made public.

A quite different scenario is also possible: that China makes completion of this rail line a matter of national pride, as it did with the construction of the Lanzhou-Xining-Gormo-Lhasa line a decade ago. If it becomes a matter of national honour, and completion a question of national pride, the economic case becomes irrelevant. Politics trumps economics.

This is clearly the case with the other major rail project announced as part of the 13th Five-Year Plan, as well as the Chengdu to Lhasa line. A railway linking China with Taiwan was also announced, without any consultations with Taiwan, a 130kms long undersea tunnel to connect the island republic to the People’s Republic.[4] Taiwan quickly repudiated the idea, and it was quickly forgotten.

TIBET IN CHINA’S CENTRAL PLAN PRIORITIES

How much the Chengdu-Nyingtri-Lhasa rail project means to China can be gauged by the official list of 60 headline projects of the 13th Five-Year Plan, which are listed in an order highly suggestive of the priorities of China’s leaders, and their fascination with high tech. The list begins with the most exciting of projects:

- “Aero-engine, gas turbine

- Quantum communication and computer

- Brain science, brain-like research

- National cyberspace security

- Deep space exploration

- Seed industry

- Clean, efficient use of coal

- Integrated information network

- New materials

- Laboratories for scientists

- 10,000 elite entrepreneurs

- 10,000 overseas talents back to China

- 1 million professionals every year

- 1,200 bases to train skilled professionals

- 800 million mu of high-standard farmland

- Internet plus modern agriculture

- Big planes

- New-generation heavy lift carrier rockets, new satellites

- Deep-sea exploration, seabed resources utilization.”[5]

As one gets towards the tail end of the 60 wish list projects of 13FYP, the excitement fizzles:

“57. 5 million km of rural road

- World-class universities

- Protection of Chinese ancient books

- Cultivating professionals capable of telling China story.”

Where do the Chengdu to Lhasa railway, and other Five-Year Plan interventions in Tibet fit, on this key list? Roughly, in the middle:

“34. Sichuan-Tibet railway

New hydro power plants with an aggregate capacity of 60,000 mw

- Big reservoirs in Tibet and other areas

- Urbanization of 100 million people in central and west China

- Ecological restoration of Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and other ecologically important areas.”

China’s 13th Five-Year Plan proposes spending at least RMB 3.8 trillion on rail projects, and the 12th FYP spend was similar; extraordinary amounts (in any currency). The national budget for railway construction in 2016 is RMB 800 m, or US$121 million, maintaining the pace of construction in recent years. In eastern China, where population densities are much higher, there is greater expectation that a business case can be made, proving these capital expenditures are justifiable.

In western China, not only are the outlays more questionable, they are openly questioned, despite the growing insistence by party leaders that they not be questioned. Zhao Jian, a professor of Beijing Jiaotong University’s School of Economics and Management, openly questions the logic behind rail lines such as the Chengdu to Lhasa railway. He writes: “Many planned railroad projects in the central and western regions were proposed based on projected demand for steel and coal. A line in the northwestern province of Qinghai, for example, was designed to transport iron ore to a steel factory in Qinghai’s Golmud. Leave aside the fact that taxes paid by steel and coal factories cannot possibly cover the cost of repairing the damage to the fragile ecosystem common in Qinghai, there is no need to develop mining and refinery businesses in the region given the central government’s goal of trimming overcapacity in these industries. This means many local governments need to reconsider their railroad development plans. In general, central and western regions should not rely on building railroads to drive growth because their population densities are low. Because rail projects usually require huge investments, their losses tend to be huge as well. The focus of rail development over the next five years should be on the transit systems in metropolitan areas.”[6]

Prof. Zhou will almost certainly be ignored, likewise his call for cost/benefit analysis. The Chengdu to Lhasa railway has been in planning for a long time, and this is not the first time funding to begin construction has been announced. Five years ago, at the beginning of the 12th Five-Year Plan much the same announcements were made. The official Work Report of the Tibet Autonomous Region government confidently stated in 2011 that construction would soon begin. TAR chairman Pema Thinley “pointed out in the work report that during the period of the 12th Five-Year Plan, construction will start on the Lhasa-Nyingtri Railroad and feasibility studies will be carried out on the Tibet sections of the Sichuan-Tibet and Yunnan-Tibet Railroads.”[7]

Megaprojects have long gestations. A project such as this is a major technical challenge, even though China has for more than a decade built more rail lines than anyone anywhere at any time. Tibet is different. But engineering obstacles are only part of the story. Neither at the start of the 12th nor the 13th Five-Year Plans was a budget for this rail line released, only a headline overall national spend. It is not clear that the project has backers of sufficient political weight, especially if, in coming years , as China’s debts mount, enthusiasm for expensive, debt-financed projects requiring 10 or even 15 years to construct, will persist. There are plenty of major projects to build “pillar industries” in Tibet that have been announced in several successive Five-Year Plans, but failed to materialise. The big copper mines are one example.

Megaprojects have long gestations. A project such as this is a major technical challenge, even though China has for more than a decade built more rail lines than anyone anywhere at any time. Tibet is different. But engineering obstacles are only part of the story. Neither at the start of the 12th nor the 13th Five-Year Plans was a budget for this rail line released, only a headline overall national spend. It is not clear that the project has backers of sufficient political weight, especially if, in coming years , as China’s debts mount, enthusiasm for expensive, debt-financed projects requiring 10 or even 15 years to construct, will persist. There are plenty of major projects to build “pillar industries” in Tibet that have been announced in several successive Five-Year Plans, but failed to materialise. The big copper mines are one example.

Without doubt, the military, especially the People’s Armed Police (PAP) will be in favour, but the military don’t finance the rail construction. PAP units from distant provinces Jiangsu, Fujian, and Henan were dispatched to assist suppression of the 2009 unrest in Xinjiang.[8] Ever since being ordered to quell the Tiananmen masses in 1989, the PLA has not been keen to be drawn into “mass incidents” which ought to be resolved by negotiation, not force.  The PLA was brought in to Tibet in 2008.[9] Yet PLA planners often insist that prevention is better than cure, which is up to local civilian leaders. But since the PLA is deeply entrenched throughout Tibet, prevention of unrest does inevitably involve PLA units that are stationed as garrisons in every major Tibetan town. Only in extreme circumstances should it be necessary to bring in extra forces from afar. But the 2008 crisis, in so many parts of Tibet, showed starkly that when local officials complacently believe their own propaganda, that the minority nationality masses are happy, and are stirred up only by foreign agitators, the situation can get out of hand, and external forces need to be brought in quickly if the masses are to be quelled. The 2008 protests and subsequent wave of public protest suicides happened mostly in the Tibetan prefectures of Kandze and Ngawa (Aba in Chinese), in Sichuan province; directly on the route of the planned Chengdu-Nyingtri-Lhasa rail line.

The PLA was brought in to Tibet in 2008.[9] Yet PLA planners often insist that prevention is better than cure, which is up to local civilian leaders. But since the PLA is deeply entrenched throughout Tibet, prevention of unrest does inevitably involve PLA units that are stationed as garrisons in every major Tibetan town. Only in extreme circumstances should it be necessary to bring in extra forces from afar. But the 2008 crisis, in so many parts of Tibet, showed starkly that when local officials complacently believe their own propaganda, that the minority nationality masses are happy, and are stirred up only by foreign agitators, the situation can get out of hand, and external forces need to be brought in quickly if the masses are to be quelled. The 2008 protests and subsequent wave of public protest suicides happened mostly in the Tibetan prefectures of Kandze and Ngawa (Aba in Chinese), in Sichuan province; directly on the route of the planned Chengdu-Nyingtri-Lhasa rail line.

NYINGTRI: A NEW HILLSTATION MAGNET

Beyond the various armed forces, and the enthusiasm of cadres stationed in Tibet for more investment, there is no obvious vested interest promoting this often-promised and often delayed rail construction project. The rail route will pass conveniently close to the Gyama copper and gold mine, upriver from Lhasa, enabling ready shipment of copper concentrates to distant smelters, if the on-site smelter, also frequently announced, fails to scale up beyond its initial experimental size. But Gyama is already not far from the existing Lhasa rail hub.

Nyingtri and nearby Bayi are both towns attractive to wealthy Chinese seeking a benign climate in summer, to escape the heat, humidity and pollution of the lowlands, especially the Sichuan basin and its megacities of Chongqing and Chengdu.

The wealth being accumulated by the new rich is staggering: China now has more billionaires than the US. Much of that wealth is now generated far inland, in Chengdu and Chongqing, primary beneficiaries of China’s drive to “open up the west.” Chengdu advertises on airport hoardings across the world that if you are one of the few remaining global top 500 companies yet to relocate to Chengdu, you’d better get in quick. You name the brand; chances are their factories are in Chongqing or Chengdu.

But the climate of these super cities in summer is stiflingly hot, humid and polluted. Think of the British in India, who similarly hated the Indian summer, its heat and monsoon downpours. The 19th century solution was the hill stations, mostly in the Himalayan foothills. Every summer, the entire British Raj ruled India from Shimla, relocating for the season from Calcutta. Dharamsala likewise was built as an idyll of Englishness, for the annual exodus from the plains, away from the press of sweaty Indians.

All stories about the new rail line from Sichuan to Lhasa emphasize Nyingtri, (in Chinese Linzhi) already a magnet for the lowland new rich. Nyingtri, roughly halfway across the plateau, well east of Lhasa, enjoys the most benign climate, warmer and wetter than Lhasa, able to grow many fruits, nuts, vegetables and with plentiful rivers. Already the luxury villas dominate the prime locations, even though technically the land remains in public ownership. Those villas are on the market, and accessible online. On Airbnb it looks almost tropical. Then there are the luxury hotels, especially in nearby Bayi, a brand new town, long a ghost town but now populated. Some are just cinderblock and reflective plate glass; others are more upmarket and feature token Tibetan embellishments.

Bayi is not a Tibetan town. Even its name is Chinese for August first, the date the People’s Liberation Army celebrates its anniversaries. It began life as a PLA military base. Nyingtri and Bayi are most definitely open for business, and the rail station will bring tourists by the millions. Mass tourism may still be a decade away yet, but it confirms that Tibet is destined to be urban, peopled by the relocated Tibetan poor relocated from the countryside, employed casually as a new proletariat, by the Han tuhao new rich enjoying their summers far from the grime of the lowlands.

But are a copper mine near Lhasa, the villas of new rich, and the military integration of the entire Tibetan Plateau into the newly formed Western Theatre Command sufficient reasons to go ahead with construction of the Chengdu-Lhasa-Nyingtri railway? This is not yet clear, in the absence of an announced budget for the project.

[1] China to build second railway linking Tibet with inland, Xinhua’s China Economic Information Service, 7 March 2016

[2] Faster than a speeding bullet: China’s new rail network, already the world’s longest, will soon stretch considerably farther, The Economist, Nov 9th 2013

[3] Asian Development Bank, Validation Report, Dali–Lijiang Railway Project, Reference Number: PVR-387, Project Number: 36432-013, Loan Number: 2116, January 2015, http://www.adb.org/documents/people-s-republic-china-dali-lijiang-railway-project

[4] Xu Wei, Cross-Straits rail still on the table, China Daily-US Edition, 10 March 2016

[5] China’s major projects to be implemented in coming five years, Xinhua’s China Economic Information Service, 7 March 2016

[6] Zhao Jian, Rail Industry Should Focus on Big Cities’ Transport Needs, Caixin, 17 March 2016

[7] “十二五”期间开工建设拉萨至林芝铁路, Construction of the Lhasa to Nyingtri railway to start during the period of the “12th Five-Year Plan”, 2011年01月12日 09:43中国新闻网, January 12, 2011, ChinaNewsNet

[8] “Map of People’s Armed Police Troops Dispatched to Xinjiang,” China Digital Times, July 10, 2009, http://chinadigitaltimes.net/2009/07/mapof-peoples-armed-police-troops-dispatched-to-xinjiang/

[9] Murray Scot Tanner, How China Manages Internal Security Challenges and Its Impact on PLA Missions, in Roy Kamphausen, David Lai and Andrew Scobell eds., Beyond The Strait: PLA Missions Other Than Taiwan http://www.strategicstudiesinstitute.army.mil/pubs/display.cfm?pubID=910

“Tibetan Riots Spread to Provinces; Protesters Torch Police Station; PLA Moves In,” Choi Chi-yuk, South China Morning Post, Monday, March 17, 2008

Jim Yardley, “As Tibet Erupted, China Security Forces Wavered,” New York Times, March 24, 2008

2 replies on “THE PLAN FOR A CHENGDU TO LHASA RAILWAY”

The analysis of the need for such a heavy expenditure on high speed trains by PRC when economy is not looking up is sound. This long term project can not be linked with One Road One Belt which is outward and seeking Chinese influence. Latter creates infrastructure in certain countries for trade.

Sichuan-Tibet railway to be completed in 2025 | China Daily (2016-11-08)

The most difficult part of the Sichuan-Tibet railway, the Kangding-Nyingchi section, will begin construction in 2018, according to the National Development and Reform Commission.

As the second railway connecting Tibet with the rest of the country, the project is expected to be completed in 2025, five years earlier than planned.

The 1,838-km track starts in Chengdu, Sichuan province, the lowlands of China’s southwestern region, and will pass through Sichuan province’s Ya’an and Kangding, and Tibet’s Nyingchi and Lhasa.

The new line will reduce the travel time from Chengdu to Lhasa to about 13 hours. It takes up to three days to drive from Chengdu to Lhasa. The other railway connecting Tibet, the Qinghai-Tibet railway, takes 21 hours from Qinghai to Lhasa.

Construction of the east and west sections began in 2014 and 2015 respectively.

The whole project will cost about 216 billion yuan ($32 billion). The highest speed the train will reach will be 200 km/h.

Sun Yongfu, an academician of the Chinese Academy of Engineering, said that the new line will travel through the most complicated geographical area in the world.

“It will cross many fault zones,” Sun said, adding that geological difficulties, including landslides, earthquakes and avalanches, will be overcome in the project.

Perched at more than 3,000 meters above sea level, and with more than 74 percent of its length running on bridges or in tunnels, the railway will meander through the mountains, the highest of which is over 7,000 meters.

It will also cross the Minjiang, Jinshajiang and Yarlung Zangbo rivers, said Lin Shijin, a senior civil engineer at China Railway Corp.

The southeast is the most populous region in Tibet, and the west of Sichuan is the least developed region of the province. The two regions are filled with breathtaking natural views and fascinating ethnic cultures.

“The railway will effectively boost tourism, bring a new Shangri-La to the world and tangible revenue to local people,” said He Ping, a tourism agency manager in Chengdu.