MODERNITY WITHOUT DEVELOPMENT

党政军民学,东南西北中,党是领导 一 切的 , the government, military, society, education, north, south, east, west — the party leads everything.

Official slogan.

Please don’t fabricate an illusion out of lies

concealing previous disasters and this current one

concealing the slaughter of countless innocent people

Poem by Woeser

The ability to respond to a crisis is one of the most fundamental abilities of an organization or individual. From the perspective of dialectics, crisis is a unity of contradictions between danger and opportunity. As a contradiction between danger and opportunity, the two sides are not absolutely opposed, but are mutually dependent, conditional, interpenetrating, dialectically unified, and can transform into each other under certain conditions.

-Qiushi (Seeking Truth), top CCP ideology journal, 20 April 2020

Blog one of two on the post corona virus new normal in Tibet

CULT OF THE STATE

The corona virus crisis is not over in Tibet, or anywhere else. Yet already we can tell what a post corona Tibet will be like. When things return to normal; it’s a new normal. In the name of normality the state is already asserting itself, advancing its agendas.

At prefectural level, the reboot of schooling, in Amdo Ngawa, means a sudden switch to Putonghua standard Chinese as the medium of instruction in all subjects outside of Tibetan language classes. The official policy of “bilingual education” in reality has narrowed its meaning to transitioning Tibetan children, earlier and earlier, from mother tongue to the official tongue of the Han Chinese race.

At national level the new normal means elaborate instructions on fulfilling the goal of total poverty alleviation by supply side solutions making use of what poor areas are best at producing, to be fed into China’s national market.

These two post-corona policy shifts might seem to have little in common. What they share is the cult of the sovereign state, as the source of all that is needful, wisely guiding locals towards assimilation, prosperity and integration into national markets, national economy and a single national identity.

It is this cult of the state that drives policy in China, across a diverse range of issues impacting on the lives of Tibetans. The cult of the state, with Xi Jinping as the infallible core leader, underpins China’s claim to uniqueness and exemption from universals such as human rights. In the worship of the state, neoConfucianists and new left neoMarxists find common ground.

The state commands all, and remains firmly in charge, directing private capital as to what to invest in. The Party is above all. This is socialism with Chinese characteristics.

During the corona virus crisis, the state advanced; after the crisis is deemed past, the state advances further. The reach of the state grew dramatically, going deep into the private lives of citizens, in the name of contagion contact tracing. When states advance, in the name of emergency, they seldom fully retreat. Instead, the state is newly legitimated by its interventions tracking the movements of all, and where those movements might have intersected with the infected.

Some are saving others’ lives

Some pray to their own gods

Some people continue doing evil, greater evil

No place exists that will not fall to the enemy

No epidemic exists that is not terrifying

No, there exists another plague far worse than this one

The official declaration of zero new infections is suspicious

A political Shangri-La does not exist

but repeating something one hundred times will cover the truth

-three corona virus poems by Woeser, 2020

THE MODERN REDISTRIBUTIVE STATE

One of the most foundational powers of the modern state is the power to redistribute. The state can through taxes capture wealth generated privately, and then redistribute it geographically or socially, from east to west, or from rich to poor. It was this power to redistribute that in Western countries was widely popular from the 1930s through 1970s, then was pushed aside by resurgent private capital. In China, in the 1990s, the state stepped back for a while, as those best endowed grew gloriously rich. But in this century the state is back, stronger than ever, as guarantor of stability and thus prosperity.

Although the World Bank and the global neoliberal order urged China to let private enterprise bloom, unhindered by regulatory state intervention, China decisively chose to persist with redistribution, distilled into the slogan of “socialism with Chinese characteristics.”

This means more than economic redistribution. The China model of socialism with Chinese characteristics includes redistribution of identity, assimilating nonHan minority nationalities into the one Chinese race, on the grounds that fluency in Putonghua Mandarin is the key to prosperity and career. Hence the slow but steady Hanification of schooling, which in the short term makes redundant all Tibetan teachers other than those also fluent in Putonghua, and those who exclusively teach Tibetan language. The bigger picture, in official eyes, is modernisation, and Tibet must modernise.

MODERNITY: GAIN & LOSS, PUSH & PULL

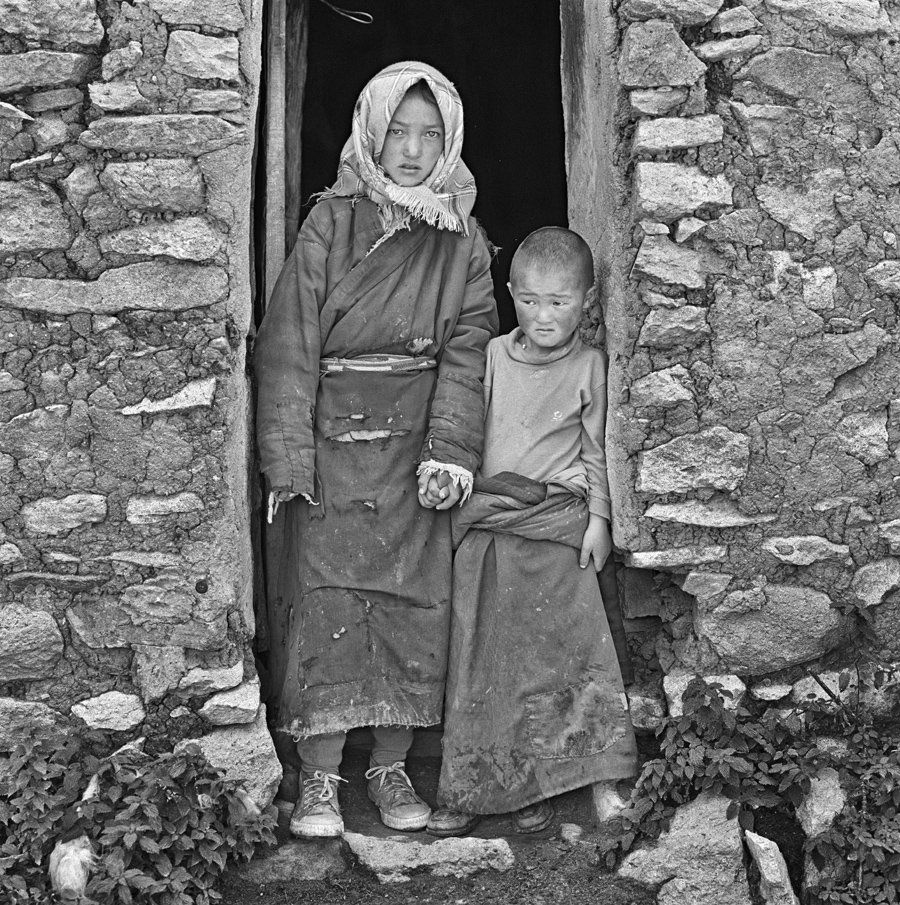

Modernisation happens over decades, at an irregular, intermittent pace most people find tolerable, as the losses are balanced by gains, or at least the promise of gains. Some of the losses are invisible until far too late. In Tibet this includes the loss of spaciousness and solitude, replaced by crowding into urban apartment blocks, often built to settle pastoralists reclassified as degraders of pasture. Modern urban life beckons, offering access to comfort, warmth, electricity, choice, consumption, health care and education, all of which were hard to access out on the range.

But modernity makes no mention of the losses. In Tibet, for 40 years or more, rural areas, rural counties and prefectures were all officially designated as “Tibetan autonomous” local governments. Municipalities have no such designation, and are open to all nationalities, with none enjoying the privileges of being the recognised owners. “Cities are never classified as ethnic, or autonomous, as we can glean from the absence of “city” in the definition of “autonomous areas” in China’s Law on Regional Ethnic Autonomy, and the fact that there are no autonomous cities in the People’s Republic.”[1]

As Tibet urbanises, the full package of modernity emerges. The economy takes on a life of its own, no longer answerable to wider Buddhist concerns about long term consequences, in this life or the next. As the economy comes to dominate, nationality and religion both shrink. Nationality is reduced to a purely private, personal choice of ethnicity, no longer a collective assertion of collective rights. Religion too becomes a purely private preference, with no role to play in the public sphere.

They actually cannot stop even in these times,

They extend their black hands toward my old friends and new acquaintances:

‘The way you talk about the plague is inappropriate.’

Preventing speech is more important than preventing the plague

In no uncertain terms, they told me I was not to speak of the following:

the Dalai Lama, Hong Kong, the pandemic, and the country of the giant infants [signifying China’s immaturity].

The advent of the coronavirus did not lead to a suspension of everyday politics; in fact, it has continued unabated. Over this period, I was repeatedly cautioned by the state security organs [not to speak out of turn] and a number of my friends, even those living quite far away, were threatened because of me. Under the conditions of totalitarianism such is our everyday reality.

-two virus poems by Woeser, plus her comments in an interview with fellow poet Ian Boyden

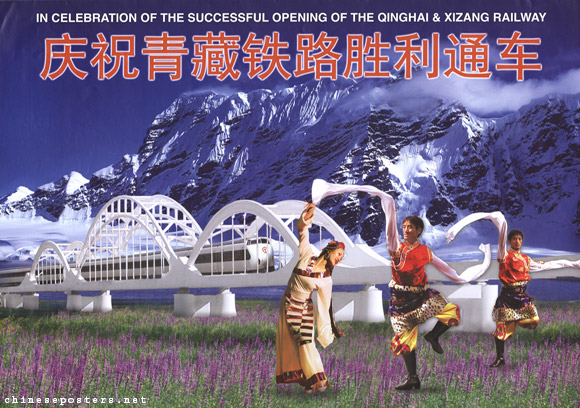

THE NEW NORMAL GROWS FROM THE BARREL OF DISASTER

Modernity may be intermittent, but sometimes it leaps forward. Disasters and pandemics are major opportunities to leap. Never let a disaster go to waste, as policy advisers often say.

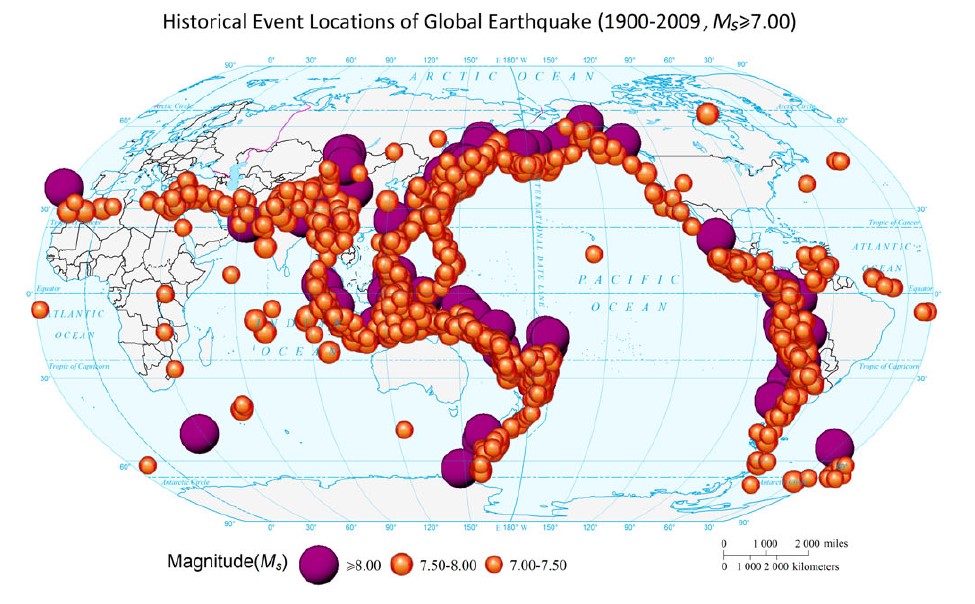

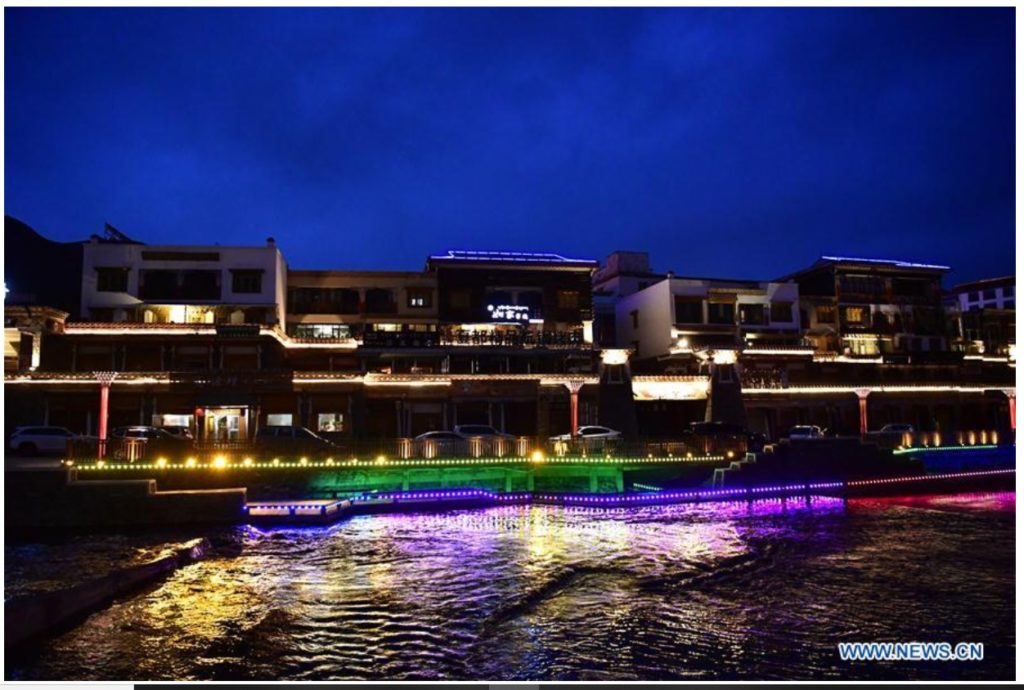

The 2010 earthquake that levelled most of Kham Yushu (Jyekundo) is a clear example. This major prefecture of Kham is allocated to Qinghai, and the Qinghai capital, Siling/Xining is 700 kms away. Until 2010 the presence of the Chinese state in Yushu was limited; the businesses (and architecture) lining the main street were mostly Tibetan.

Three months after the Yushu earthquake the State Council in Beijing issued a lengthy reconstruction plan, 重建目标, full of slogans, somewhat vague on specifics. The plan was to build a beautiful socialist jade tree of development, ecology and harmony, 为建设生态美好、特色鲜明、经济发展、安全和谐的社会主义新玉树奠定坚实基础, Wèi jiànshè shēngtài měihǎo, tèsè xiānmíng, jīngjì fāzhan, ānquán héxié de shèhuì zhǔyì xīn yùshù diàndìng jiānshí jīchǔ.

The earthquake was an ideal opportunity to rebuild Yushu city with Chinese characteristics. Now Yushu looks much like any third or fourth tier Chinese city, its’ central business district dominated by Han Chinese businesses and offices, in high rise blocks indistinguishable from hundreds of cities across China. Tibetans are on the fringes. In the name of scientific earthquake reconstruction a major monastery was shifted from its secluded location and rebuilt as a tourist attraction on the road from airport to city. Yet on any geological map of the earthquake-prone faults underneath Yushu, the new locations remain as vulnerable as the old.

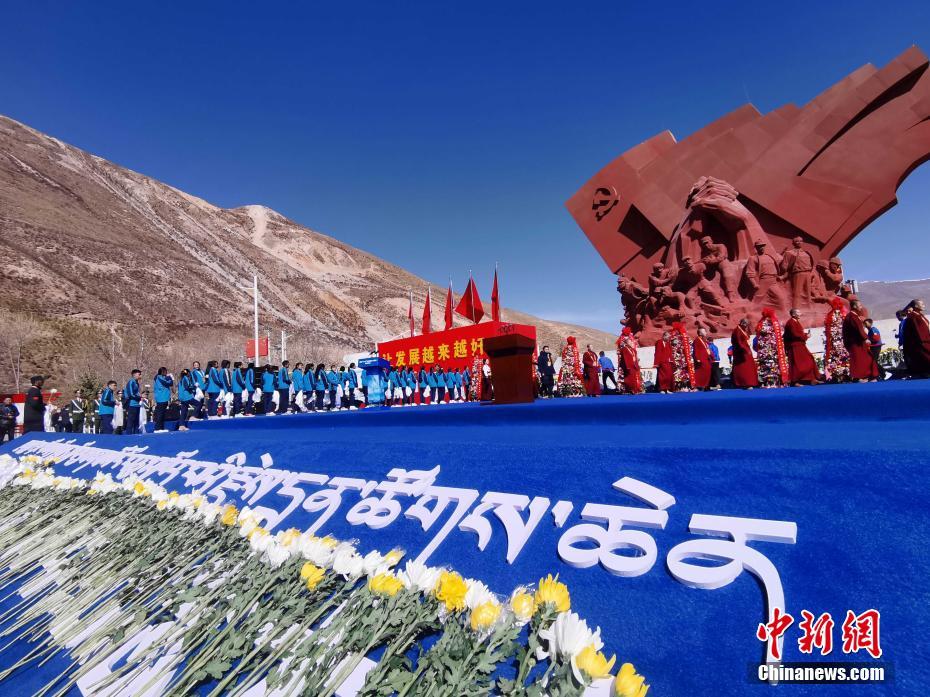

Central leaders have often named disasters as the moment for the party to demonstrate its capabilities, as author of all recovery efforts, sometimes to the exclusion of community grassroots initiatives. Anthropologist Charlene Makley calls this “spectacular compassion.”[2] Ethnographer Christian Sorace, in a 2017 book on the 2008 earthquake at the foot of the Tibetan Plateau, in Wenchuan, notes: “The performance of Party benevolence, compassion, and reputation was not empty propaganda; it required a top-down process of political control over each phase of the reconstruction process. As academics inside China observed early on, ‘the earthquake reconstruction contains the possibility of a concealed tendency: the unlimited expansion of the scope of state power to represent public authority and control allocation of resources.’ The ‘unlimited expansion’ of state power also meant increased pressure on the Party to perform “miracles” (qiji) in the earthquake zone. Why, however, would the Party stake its reputation, image, and legitimacy on a utopian promise to engineer “great leaps of development” (kuayueshi fazhan) in two years of breakneck reconstruction activity?”[3]

April 2020, in the midst of the virus crisis, was the 10th anniversary of the earthquake in Yushu, and all sections of Tibetan society had to gather at the memorial celebrating China’s generosity, and perform gratitude. The monks had to do monastic dances, the school children calisthenics, and everyone dutifully displayed their grasp of compulsory gratitude education, 感恩教育, gan’en jiaoyu.

DOES POVERTY ALLEVIATION MEAN DEVELOPMENT OR DISPLACEMENT?

China’s redistributive state also set itself the target of 2020 as the year in which all poverty is eliminated. Socialism with Chinese characteristics demands no-one be left behind, and China, once successful, will yet again become the exemplary model for other developing countries to emulate.

The problem, according to official classifications of poverty, is that the poorest people are in areas of contiguous destitution, defined as adjoining areas lacking endowments, 个集中连片特困区贫困 Gè jízhōng lián piàn tèkùn qū pínkùn, where there is only thin soil or bare rock, trees and most crops cannot grow, the climate is so cold, the air so thin. In short: Tibet as seen through Han eyes as somewhere no-one would choose to live, if they had a choice. In the long run, the benevolent redistributive state could find somewhere else for these poverty stricken destitutes to live, but the target is to end all poverty quickly, in 2020. Targets are to be met, and all cadres at all levels are instructed, in considerable detail, how to do it. And they are not to be deflected by the pandemic, which officially is no excuse for meeting their target on time.

Those are the key points in the decrees of the State Council Leading Group Office of Poverty Alleviation and Development (CAPD), issued in February 2020.

For Tibetans, these decrees make odd reading. First, all poverty in Tibet is officially already ended, in January 2020, immediately before corona virus lockdowns and infections sent people back into poverty. Second, poverty is widespread in Tibet, both because the customary mode of production, especially pastoralism, thrives on seasonal uncertainty, and sometimes fails due to unseasonal extremes. Chinese public health scientists recently confirmed what all Tibetans know: the higher you are in altitude, the further away you are from access to even the most basic health care, and little of Tibet is below 4000m. Centralisation of services has been official policy in recent years, with as many as 80 per cent of local primary schools permanently closed in the past few years, while county boarding schools have expanded.

Third, and oddest of all, is the poverty agenda announced by the State Council Leading Group Office of Poverty Alleviation and Development (CAPD), and its specific directives for Tibet. The suggestions it makes are all sensible, proposing linkages between rural producers and urban consumers, utilising the comparative advantages remote areas have in producing specific products. This is development economics 101, elementary starting points for actually doing development.

This 2020 decree hits all the right notes: “As a starting point, with the aim of expanding income channels for poor households, stabilizing poverty alleviation achievements, and focusing on promoting the stable sales of poverty alleviation products, the effective supply of urban “vegetable baskets” and “rice bags” and the healthy development of poverty alleviation industries in poor areas will be promoted to meet the needs of urban residents. Upgrade and help the poor to continue to increase their income and build a long-term social poverty alleviation mechanism.

“Second, adhere to the basic principles: Insist on combining the development of the masses in poverty-stricken areas with the aim of increasing production and increasing poverty alleviation, and solving the urban “vegetable basket” and “rice bag” problems. Give full play to the resource advantages and ecological advantages of poverty-stricken areas, organize the supply of poverty alleviation products, ensure the quality of agricultural products and food safety, accurately meet the needs of residents in eastern regions and large and medium-sized cities for high-quality safe poverty alleviation products, and solve the problems of “vegetable baskets” and “rice bags” To achieve complementary advantages and mutual benefit.”

This is textbook stuff. Xinjiang has good climate and soils for growing melons, grapes and cotton. Inner Mongolia has grasslands well suited to dairy herds. Tibet has always excelled, highly productively, at wool, dairy,butter and barley cropping, None of this is new, nor obscure knowledge accessible only to a few. It is obvious to anyone with eyes.

Indeed, China did intensify melon, grape and cotton production in Xinjiang decades ago, eclipsed in recent years by a boom in coal and oil-fired electricity production, aluminium smelting and mass Han employment manning detention centres. In Inner Mongolia China did intensify dairy production, to such an extent that most of China’s domestic production of milk, yoghurt, milk powder and infant formula now comes from Inner Mongolia. So how come so little happened in Tibet, even though China considers itself the leading developmentalist, champion of the developing world?

LIFTING TIBETAN LINKAGES TO PROSPEROUS CHINESE MARKETS?

This latest state decree on poverty is very clear that this is a geographic problem, with demand concentrated in eastern China, and poverty in western China, including Tibet: “Adhere to the combination of poverty alleviation through consumption and poverty alleviation through cooperation between the eastern and western regions. Take the sales of poverty alleviation products as an important content to evaluate the effectiveness of poverty alleviation collaboration and targeted poverty alleviation work in the east and west, and promote the cooperation between east and west poverty alleviation cooperation regions and central units in consumption Poverty alleviation action.”

Again, this is all elementary, and has been said many times before. What is new this time is that a newly wealthy China is allocating money to finance implementation of this strategy:

“The main ways of consumer poverty alleviation: (1) The government procurement model is for budget units to purchase agricultural and sideline products in poor areas; encourages budget units at all levels to purchase poverty alleviation products through priority procurement and reserved procurement shares.

(2) The government leads the establishment of a cooperation model for poverty alleviation between the east and the west in the consumer poverty alleviation trading market. Poverty-stricken areas should focus on the identification and supervision of poverty-relief products, organize poor people to develop characteristic poverty-relief industries with market demand and local advantages, build brands, improve quality, and ensure supply. The central provinces should use their geographical advantages to organize local cities and poor areas to establish long-term stable supply and marketing relations.

(3) Participation model of market entities for various enterprises selling poverty alleviation products. Encourage and guide various enterprises to give full play to their own advantages, use their own platform channels, and actively promote poverty-relief products to enter the market, enter the supermarket, enter the school, enter the community, enter the cafeteria, etc.”

Again, this is all admirable, if it means capital expenditure and real investment in the vastness of the Tibetan Plateau, linking Tibetan producers, drogpa, samadrog and shingpa, pastoralists, farmers and those who mix both, to urban consumers with a taste for yoghurt, cheese tea and wool as a fashion statement. Cheese tea is a highly fashionable item in China. China is no longer wary of dairy, the Wall Street Journal tells its investor audience. The potential market is huge. What is questionable is the scale of actual investment.

GOVERNMENT IS HERE TO HELP?

Better yet is a rhetorical emphasis on local initiative rather than top down control: “Consumer poverty alleviation actions follow the principle of voluntariness, respect the laws of the market, and do not engage in administrative apportionment, compulsory orders, target tasks and ‘one size fits all’. Ensure that the quality of poverty alleviation products are qualified, the prices are reasonable, and poverty is real, and resolutely prevent poverty alleviation under the banner of accumulating wealth for profit.”

So when it comes to Tibet, does this State Council instruction specify what to focus on? “Give full play to the role of the consumer poverty alleviation platform of the China Social Poverty Alleviation Network, focus on the deepest poverty-stricken areas, focusing on Tibetan barley, yak and southern Xinjiang jujube, walnuts, etc.”

At this point it all gets a bit vague. If this actually works out as planned, it could indeed do much to improve cash incomes across Tibet, even generate wealth, not just in areas blessed with yartsa gumbu caterpillar fungus and matsutake mushroom to be flown to Japan, in the boom areas of Tibet. Value adding and marketing barley, yak hair, dzo milk, sheep wool, goat cashmere fibres for urban use are just what Tibet needs.

So how come it has taken China six decades of persistent under-investment, to discover these basic truths? What wasn’t all of this done 60 years ago in the “Great Leap Forward”?

If not 60 years ago, why not 45 years ago, as China emerged from the Cultural Revolution and turned decisively to market capitalism?

If not 45 years ago, why not 35 years ago, when Hu Yaobang was in charge, promising liberal reforms, and wool cleaning mills flourished briefly and then collapsed?

If not 35 years ago, why not 25 years ago? The 1996 Ninth Five-Year Plan for Tibet, for example, specified, at length: “The direction and main aims of development are: to improve preferential policies to encourage and support economic entities from China’s interior to set up industries in Tibet; continue to do a good job in economic co-ordination with Yunnan, Guizhou, Sichuan and Guangxi; and vigorously develop exchanges and economic ties with coastal provinces, and to form a pattern of opening our doors……… Through regional planning and industrial policy, we will establish and develop the economies in various areas and a rational division of labour and eventually achieve the target of joint development and common prosperity……. According to the requirements for building a large-scale market network, developing large-scale trade, and invigorating the large-scale circulation of commodities, we will accelerate the construction of a unified, open, competitive and orderly market network.”[4]

If not 25 years ago why not 15 years ago, at the height of the Open up the West, xibu da kaifa, campaign? That was also the height of the aid-Tibet program, in which central leaders pressed rich provinces and corporations to adopt specific towns or counties in Tibet, and launch projects intended to transfer technology and training to remote areas, to lift Tibet out of poverty.

POLICY FAILURE OR RACIST PREJUDICE?

Nothing much happened to raise incomes in rural Tibet 60 or 45 or 35 or 25 or 15 years ago, despite the promises. China, in its frequent White Papers on Tibet, prides itself on implementing the global “laws” of development, which have just been reiterated by the February 2020 State Council announcement on comparative advantage. The reality is that China has failed to develop the long standing, indigenous, autochthonous, customary Tibetan economy of livestock and barley. Instead China imposed an economy from above, an economy of infrastructure -highways, dams, power grids, railways and urban construction- that cemented Chinese rule, employed Han immigrants, while doing very little to provide employment, market access or value adding for Tibetans and their abundant surpluses.

Why this under investment? Why six decades of neglect of the actually existing Tibetan economy? Why this failure of development? The only plausible explanation is racist disdain for the ungrateful, rebellious Tibetans, going back to the 1950s. China has persistently seen the land of Tibet as huang, ye, xu and kuang, 荒地,驯服,野蛮,空旷,广阔 wasteland, untamed, barbaric, empty and vast; and the Tibetans as luohou, pinkun and pianpi, 落后, 贫困, 偏僻 backward, poor and peripheral.

Many Tibetans, having heard promises of development, linkage and market access many times, are understandably cynical, as if this is just another propaganda ploy.

Since poverty remains entrenched in Tibet, made worse by lack of access to health care in the middle of a pandemic, let’s hope this time the State Council means it. Any approach that builds on Tibetan strengths is surely preferable to making Tibetan pastoralists landless, removing them to urban fringes, in the name of repairing degraded grasslands. Is this a sign of progress?

NO VIRAL EXCUSES

Only three days after this State Council diktat was issued 14 February 2020, a further decree was issued, specifically denying local cadres any coronavirus excuse for failing to implement this command by central leaders. Instead of the pandemic trumping poverty alleviation, the State Council showed a clear-headed understanding that the virus is going to exacerbate poverty, so more central finance will be made available, to make sure the poor don’t slip into destitution.

The 17 February 2020 decree is brief and blunt. It commands local governments to: “Accelerate the allocation and disbursement of funds. In 2020, the central government will continue to increase the scale of special poverty alleviation funds by a large margin, and the allocation of new funds will be appropriately tilted towards the regions affected by the epidemic. Provinces (autonomous regions, municipalities directly under the Central Government, hereinafter referred to as provinces) should continue to guarantee the investment of special fiscal poverty alleviation funds, give preferential support to the cities and counties that are heavily affected by the epidemic in the allocation of funds, and effectively guarantee the need for poverty alleviation in these areas. Reduce the impact of the epidemic on poverty alleviation.”

The State Council calls for: “focus on industrial projects, and to increase the support for the production, storage, transportation, and sales of industrial poverty alleviation projects that have been greatly affected by the epidemic in order to solve the problem of “difficulty in selling”. Support poor households to resume production, carry out self-rescue in production, create conditions to encourage poor labour to find jobs and start businesses. Poor households can be given one-time production subsidies and loan interest discount support. Strengthen employment support, and appropriately arrange special fiscal poverty alleviation funds to organize and stabilize the jobs of the poor. To meet the needs of epidemic prevention and control, new temporary jobs such as cleaning and sanitation, epidemic prevention and elimination, and patrol duty will be given priority, and the placement of poor labour will be given priority. Poor laborers who go out to work in accordance with the regulations shall be provided with transportation and living expenses subsidies. Make every effort to guarantee the basic lives of the poor.”

Unlike the vague language of propaganda, this is detailed and specific, and backed by central funds. This is a redistributive state redistributing wealth to those in greatest need.

Only time will tell if it actually happens. But we can ask now why official China feels it needs to make such announcements?

This is the heart of what China means by socialism with Chinese characteristics. China wants to be exceptional in every possible way, not bound by global norms, institutions, values, laws and conventions. China demands to be judged solely on its own announced criteria. The next blog looks deeper into this cult of the state.

Tibetan poet Woeser: “This work is also a political critique. In particular, it is a critique of that vast political plague, although I only hint at that in a veiled fashion because I am actually quite frightened. The political plague and the oppression that it has occasioned never eased up during the time that I was writing these poems.

“Over time, China has repeatedly been infected by this ‘other plague’, one that has increased in intensity until it has become a chronic affliction. It may, in fact, prove to be incurable. As a Tibetan I have particularly strong feelings on this subject.

“The line ‘there exists another plague far worse than this one’ is the kernel of the work. So, yes, by ‘another plague’ I am referring to a political plague — tyrannical governance as well as the actual organs of repression and the thuggish sway in which it operates. Tyranny is akin to a virus. When I write of the ‘other plague’, I am talking about many things: destiny, the fate of humanity, as well as the dictator, regardless of which.”

[1] Uradyn E. Bulag, Alter/native Mongolian identity: From nationality to ethnic group, in Perry, Elizabeth J.; Selden, Mark, eds. Chinese society: change, conflict and resistance. Routledge 2010

[2] Charlene Makley, SPECTACULAR COMPASSION: “Natural” Disasters and National Mourning in China’s Tibet, Critical Asian Studies, 46:3 (2014), 371-404

[3] Christian P. Sorace, SHAKEN AUTHORITY: China’s Communist Party and the 2008 Sichuan Earthquake, Cornell, 2017, 17-18

[4] Xizang Ribao (Tibet Daily) 7 June 1996