blog three of three on corona virus and Tibet

For China, corona virus in Tibet starts and ends with data on individuals and the zealous tracking of all the contacts of infected individuals. Like all big data aggregations, this lends itself to immediate publication on official prefectural websites, often with specific biodata, everything but personal name, on those infected.

WHAT ARE THE OPTIONS, IF VIRUS INFECTION ENDANGERS LIFE?

Prompt publication of data built on intensive and intrusive tracking of everyone who might be infected is the end of the story, for official China.

For Tibetans, that story then begins. Having had white coated health professionals rush through the streets, alarming everyone, trying to nail every person in contact with an infected person, what do you then do if you are now officially labelled as a corona virus case, or a likely case with no symptoms yet? Your biodata has been published on an official website. You have been ordered to stay home, in strict self-quarantine. But what happens if you do develop a corona virus infection, and urgently need treatment when you quickly become short of breath?

In rich countries, with abundant access to information, people know to expect the crisis to come on the eight day after symptoms manifest, as the immune system goes into overdrive and starts lining your lungs so bad you are shorter and shorter of breath. Then you need help quickly, as deterioration is usually rapid, and extra oxygen may be all you need, rather than highly invasive ventilator.

But in Tibet, what can you do? Waiting, as symptoms worsen, is not a good option, as that only increases the likelihood you will end up needing a ventilator. The problem with ventilators is that they exist only in cities, are expensive to buy and to operate, as they require having an anaesthetist on hand to keep the patient sufficiently sedated to tolerate having a tube thrust deep into the lungs, forcing in oxygen through clogged lung walls and into the blood stream.

In Western countries there is an obsession with ventilators, and much argument about whether there are enough, how to get more, who is to blame. Yet the reality ignored by many is that a ventilator is a last resort, a desperate measure, that in 50% of cases, still results in death.

What matters much more, as the infection progresses, is that key transition, usually on the eighth day of being ill, when the immune system starts over reacting, clogging the lung wall. This requires a rapid transition from self-isolation to hospital admission.

In rich countries, that is often problematic. Many people wait at home too long. Many find it hard to get an ambulance to come. Many get to a hospital only to find it overloaded and understaffed as health workers themselves increasingly fall ill. There is not much point in encouraging Tibetans to go to hospital as needed, when it’s urgent, if they can’t get in.

TREATING CORONA VIRUS CASES IN TIBET

In Tibet the obstacles to timely and effective treatment, in that critical period, are multiple. As well as the complications experienced by the rich, Tibetans have to overcome the stigma of being labelled a danger to public health, to be hidden away, in order to be accepted as an inpatient in a hospital. You have to get to a hospital, which may be far. You may find the county hospital giving preferential treatment to the well-connected and/or Han urban residents, who have the money to pay scalpers charging huge amounts to sell you a ticket to the hospital’s outpatient queue, where you may then be assessed for inpatient admission.[1] Even in big Chinese cities, even with supposedly universal health care insurance, you still need to bribe your way into a hospital bed, starting with paying whatever the scalper demands. You need cash upfront, or you may not even get through the front door, still less into a hospital bed.

In Tibet the quickest path into poverty is illness, anyone in the family sick or injured. Although China has officially abolished all poverty in Tibet, the risks remain. For China, officially ending poverty is a one-way trajectory, with no sliding back, but in Tibet everyone knows anything can happen, life is contingent, a snowstorm can wipe out half your yaks overnight, a slip into a marmot burrow can break a leg.

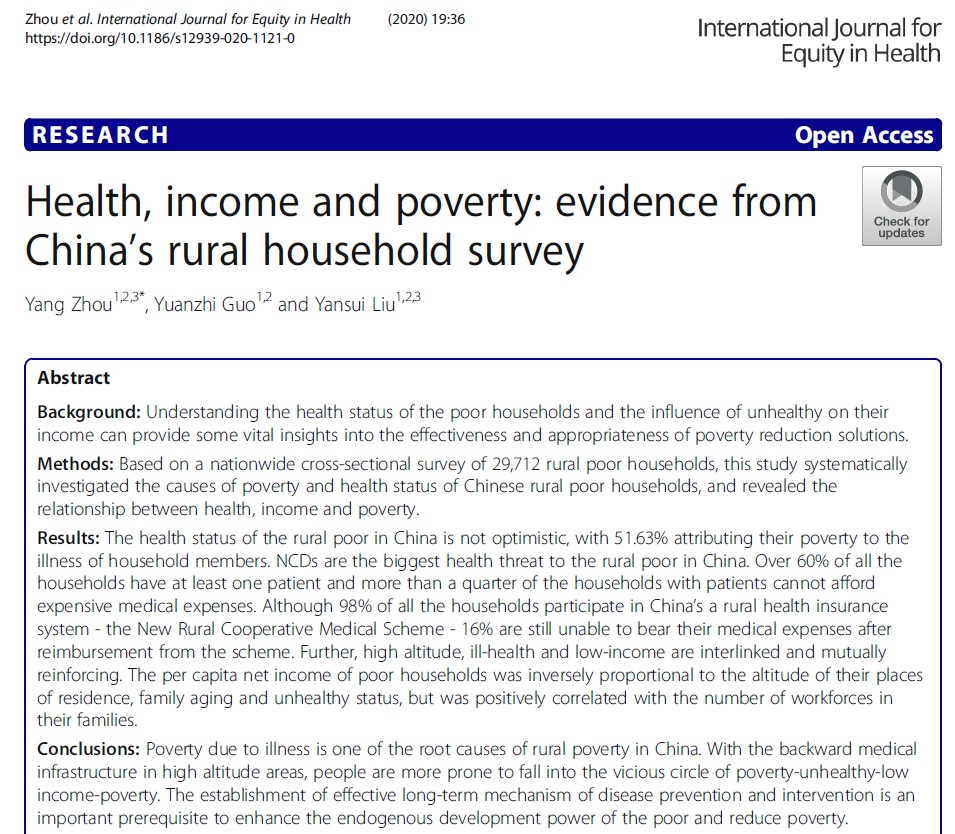

A 2020 freely downloadable article by Chinese scientists, based on a nationwide cross-sectional survey of 29,712 rural poor households, concluded: ”The health status of the rural poor in China is not optimistic, with 51.63% attributing their poverty to the illness of household members. Non Communicable Diseases are the biggest health threat to the rural poor in China. Over 60% of all the households have at least one patient and more than a quarter of the households with patients cannot afford expensive medical expenses. Although 98% of all the households participate in China’s a rural health insurance system – the New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme – 16% are still unable to bear their medical expenses after reimbursement from the scheme. Further, high altitude, ill-health and low-income are interlinked and mutually reinforcing.

“The per capita net income of poor households was inversely proportional to the altitude of their places of residence, family aging and unhealthy status, but was positively correlated with the number of workforces in their families. Poverty due to illness is one of the root causes of rural poverty in China. With the backward medical infrastructure in high altitude areas, people are more prone to fall into the vicious circle of poverty-unhealthy-low income-poverty. At present, most of China’s poverty-stricken population is concentrated in the deep mountainous areas. For every 1000m increase in altitude, net income per capita will decrease by CNY/RMB 120.

“Furthermore, geographical position, ill-health and poverty are interlinked and mutually reinforcing. The elevation of farmer’s residence affects medical infrastructure or services, thus affecting human health and family income. The higher the altitude of the farmer’s residence, the lower the level of medical services they enjoy, and the worse their health. Therefore, there is a significant negative correlation between the altitude of the farmer’s residence and the health status.”[2]

CROSS-SPECIES INFECTIONS IN TIBET

Dangerous infections jumping from animals to humans are not new to Tibetans. Yungdrung Gyurme, in his village beyond Shigatse over the new year discovers “the experience of the older generation regarding epidemics dates back to the last century. My father once told me about an epidemic in the 1970s. A villager had been infected with a scary disease transmitted from a dead yak. He got a rose-like rash on his body and soon died. His family was in a horrible situation, no one dared to help them remove the body, they went everywhere holding out their thumbs pleading for help (Tibetans stretch out their thumbs when they plead for help). In the end, they buried the body in the soil; Tibetans, however, had been holding sky burials since the 13th century and believe that when you bury the deceased, it will bring disaster to the following generations. So they later started digging out all the bones and only felt at ease when the body was burnt.”

Yungdrung Gyurme tells us this story, in his posting on the impact of corona virus in remote Tibetan villages, without telling what the disease was, despite his allegiance to scientific rationality. That this dramatic contagion should, even in 2020, remain mysterious, says a lot about the lack of effort by official China to feed back to Tibetans the voluminous research done on hydatids, and the nasty, often fatal, disease this inter-species transmission causes. Echinococcosis is a very unpleasant way to die.[3] Same goes for brucellosis.

HEALTH CARE IN CHINA: THEORY AND REALITY

On paper, China has a comprehensive health insurance system that reimburses you for the health bills you’ve paid. On paper, the urban health insurance system and its rural equivalent merged in 2019, bringing greater reimbursement payments to rural folk, with only a modest increase in insurance subscription payments. In reality, it is still true that “rural families often borrow money, sell their productive assets, or cut short their children’s education in order to pay their medical expenses, or simply do not go to see the doctor when falling ill due to their inability to pay.”[4]

The lack of the right connections and lack of cash are the biggest health hazards in Tibet, often compounded by doctors insisting on prescribing the most expensive medicines and treatments, which remains a major source of their income. Tibetans, due to remoteness and membership of a disdained ethnicity, are at the end of the line, still queuing even when the need for treatment is urgent.

Then there’s the shortage of health care professionals in rural areas. According to the UN International Labor Organisation’s World Social Protection Report 2017-2019, 29.1 per cent of China’s rural population has no effective health cover because of a deficit of health professionals.

The ILO report was published to track each country’s progress towards achieving the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals, especially SDG3, universal health care. That requires not only emergency hospital care but long term care (LTC) that enables people, after discharge from hospital, to live independently, with access to ongoing health services as needed. Although China boasts it leads the developing world in delivering fulfilment of the Sustainable Development Goals, China spends only 0.1 % of its GDP on long term care, according to ILO data tables. By comparison Belgium spends 1.7% of GDP on LTC, the Netherlands 2.2%.

China spends $133 per older citizen per year on long term care, a figure inflated by calculating purchasing power parity, which assumes renminbi expenditure gets you more than do dollars in other countries. But that $133 per over-65, the ILO tells us, is not a lot; and way below the $450 South Africa spends, or $186 in Indonesia, or $3838 in Belgium.

China has long underspent and underinvested in health care, which is not a problem for the urban rich, but, on ILO figures, 91% of China’s population older than 65 are excluded from LTC services due to financial resource deficit. The health insurance system requires local governments to contribute, as well as central payments and the regular insurance payments by families opting to be covered. The result is a highly unequal system, with poor counties only able to finance poor health (and education) services. This has been so for many decades now.

The UN has had since the 1950s a Convention binding signatory governments to provide social protection to all citizens, ILO Convention 102. China has never signed it.

PANDEMICS AND HUMAN RIGHTS

China’s downshifting of responsibility for so much of the financing of health and education, down to local level, favours rich provinces and prefectures, while depriving poorer areas of resources. Michelle Bachelet, speaking for the UN response to corona virus, says: “In developing countries, where a large portion of the population may rely on daily income to survive, the impact could be far greater. The millions of people who have little access to health-care, and who, by necessity, live in cramped conditions with poor sanitation, and no safety net, no clean water, will suffer most. They are less likely to be able to protect themselves from the virus, and less likely to withstand a sharp drop in income. Unchecked, the pandemic is likely to create even wider inequalities, amid extensive suffering.

“An emergency situation is not a blank check to disregard human rights obligations. I am profoundly concerned by certain countries’ adoption of emergency powers that are unlimited and not subject to review. In a few cases, the epidemic is being used to justify repressive changes to regular legislation, which will remain in force long after the emergency is over. In some countries we have already seen reports of journalists being penalized for reporting a lack of masks; health-workers reprimanded for saying they lack protection; and ordinary people arrested for social media postings about the pandemic. Criticism is not a crime. When an existential threat faces all of us, there is no place for nationalism or scapegoating – including of migrants and minority communities.”

If you missed Michelle Bachelet’s statement, you aren’t alone. When the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights speaks thus, on April 9, it gets almost no media coverage, in a time when everyone is scared for themselves.

SURVEILLANCE LEGITIMATED?

China’s pervasive surveillance technologies have perhaps legitimated themselves by their use in the virus crisis in swiftly tracking everyone who came into contact with someone who turned out to be infected. This constant surveillance could readily become the new normal, not only across China, but in other countries too. Now Apple and Google, normally rivals, are collaborating on designing apps you can (voluntarily) download and use to see if your path crossed with anyone infected, because they too have downloaded the app.

While China continues to fail to invest in rural health care in Tibet, the surveillance state is surging. “The police authorities in China are using these tools to create a powerful surveillance dragnet and racially profile minorities. Such acts of the Chinese government are giving rise to a fear that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) will rule via Digital Authoritarianism, i.e., state-led mass surveillance using a new form of credit scoring to influence the behavior of citizens.”

China is energetically promoting its health care system and its mass surveillance technologies to developing countries, especially in 50 African countries. The China model promises universal health care at modest prices for central governments, and intensive surveillance of citizens on the move, as essential tools for pandemic case contact tracing.

When Tibetans speak up about the realities of a virus first transmitted to humans in Wuhan, of unavailable treatment, they are speaking truths many need to hear.

STRENGTH IN A TIME OF PANDEMIC

Over and over Tibetan culture has rediscovered its inner strengths in the most testing times. The trust so many Tibetans have in the Buddhas and bodhisattvas means they are not alone, and have active guidance available, as long as they ask for it, as heartfelt as possible.

This has most recently been expressed poetically by Dzongsar Jamyang Khentse Rinpoche:

Master Shakyamuni, think of me!

Lord Khasarpani, think of me!

Only father Oddiyana Padma, think of me!

Only mother Tara, think of me!

Glorious sister Kali Devi, think of me!

Pay heed to this person’s prayers and desperate plea!

Purify the effects of negative actions,

Remove obstacles and adverse circumstances,

Free us from the grasp of malicious spirits,

Pacify the sufferings of plague,

Destroy the root of destructive epidemics,

Pacify wars and disputes.

If I don’t pray to you, to whom should I pray!

If you don’t care for us with compassion, who will care for us!

If you don’t protect us with your power, who will protect us!

Bless us!

Bless us right now!

Bless us this very day!

Bless us this very moment!

Bless all beings that they encounter the Three Supreme Jewels,

Bless all beings that they have faith in the Three Supreme Jewels,

Bless all beings that they develop conviction in cause and effect,

Bless all beings that compassion and bodhicitta arise within them,

Bless all beings that they understand the meaning of shunyata,

Bless all beings that they recognize their mind as Buddha.

May this person’s aspiration be realized!

[1] Hospital Scalpers Anger Many, Stay in Business Anyway, Caixin Online, 02.29.2016

[2] Yang Zhou, Yuanzhi Guo and Yansui Liu , Health, income and poverty: evidence from China’s rural household survey, International Journal for Equity in Health, vol 19, 2020, article 36 free from https://equityhealthj.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12939-020-1121-0

Liu Y, Liu J, Zhou Y. Spatio-temporal patterns of rural poverty in China and targeted poverty alleviation strategies. Journal of Rural Studies, 2017;52:66–75.

[3] Lass A; Ma L; Kontogeorgos I; Xueyong Z; Li X; Karanis P, Contamination of wastewater with Echinococcus multilocularis – possible implications for drinking water resources in the Qinghai Tibet Plateau China. Water research 2020 Mar 01; Vol. 170, pp. 115334

Boufana B; Umhang G; Qiu J; Chen X; Lahmar S; Boué F; Jenkins D; Craig P, Development of three PCR assays for the differentiation between Echinococcus shiquicus, E. granulosus (G1 genotype), and E. multilocularis DNA in the co-endemic region of Qinghai-Tibet plateau, China. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene 2013 Apr; Vol. 88 (4), pp. 795-802

Wang X; Liu J; Zuo Q; Mu Z; Weng X; Sun X; Wang J; Boufana B; Craig PS; Giraudoux P; Raoul F; Wang Z, Echinococcus multilocularis and Echinococcus shiquicus in a small mammal community on the eastern Tibetan Plateau: host species composition, molecular prevalence, and epidemiological implications. Parasites & vectors 2018 May 16; Vol. 11 (1), pp. 302

Chen, Fan; Liu, Lei; He, Qili; et al, A multiplex PCR for the identification of Echinococcus multilocularis, E. granulosus sensu stricto and E. canadensis that infect human, PARASITOLOGY; OCT 2019; 146; 12; p1595-p1601

王展; 胥瑾; 王海久; 周瀛; 任利; 阳丹才让; 侯立朝; 樊海宁Establishment of animal model for Echinococcus inoculation infection in Microtus fuscus in Qinghai – Tibet Plateau. 泡球蚴感染青藏高原野生田鼠动物模型的建火. Journal of Clinical Hepatology / Linchuang Gandanbing Zazhi. Feb2018, Vol. 34 Issue 2, p373-377.

Gao CH; Wang JY; Shi F; Steverding D; Wang X; Yang YT; Zhou XN, Field evaluation of an immunochromatographic test for diagnosis of cystic and alveolar echinococcosis. Parasites & vectors 2018 May 23; Vol. 11 (1), pp. 311;

Li, Jian-qiu; Li, Li; Fan, Yan-lei; Fu, Bao-quan; Zhu, Xing-quan; Yan, Hong-bin; Jia, Wan-zhong. Genetic Diversity in Echinococcus multilocularis From the Plateau Vole and Plateau Pika in Jiuzhi County, Qinghai Province, China, FRONTIERS IN MICROBIOLOGY; NOV 5 2018;

Moss JE; Chen X; Li T; Qiu J; Wang Q; Giraudoux P; Ito A; Torgerson PR; Craig PS, Reinfection studies of canine echinococcosis and role of dogs in transmission of Echinococcus multilocularis in Tibetan communities, Sichuan, China. Parasitology 2013 Nov; Vol. 140 (13), pp. 1685-92;

Cai, Qi-Gang; Han, Xiu-Min; Yang, Yong-Hai; Zhang, Xue-Yong; Ma, Li-Qing; Karanis, Panagiotis; Hu, Yong-Hao. Lasiopodomys fuscus as an important intermediate host for Echinococcus multilocularis: isolation and phylogenetic identification of the parasite, INFECTIOUS DISEASES OF POVERTY; MAR 31 2018;

Abulizi, Abuduaini; Wen, Hao; Zhang, Chuanshan; Li, Liang; Ran, Bo; Jiang, Tiemin; Aji, Tuerganaili; Shao, Yingmei. Sequence analysis of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase 1 and cytochrome b genes of echinococcus multilocularis from human patients, INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF CLINICAL AND EXPERIMENTAL PATHOLOGY; 2018; 11; 2; p795-

Cao, M.; Chen, K.; Li, W.; Ma, J.; Xiao, Z.; Wang, H.; Gao, J. Genetic characterization of human-derived hydatid fluid based on mitochondrial gene sequencing in individuals from northern and western China. Journal of Helminthology. 2020, Vol. 94, p1-5.

Role of dog behaviour and environmental fecal contamination in transmission of Echinococcus multilocularis in Tibetan communities. Parasitology 2011 Sep; Vol. 138 (10), pp. 1316-29;

Craig PS; Giraudoux P; Wang ZH; Wang Q, Echinococcosis transmission on the Tibetan Plateau. Advances in parasitology 2019; Vol. 104, pp. 165-246

Jian-qiu Li; Li Li; Yan-lei Fan; Bao-quan Fu; Xing-quan Zhu; Hong-bin Yan; Wan-zhong Jia. Genetic Diversity in Echinococcus multilocularis From the Plateau Vole and Plateau Pika in Jiuzhi County, Qinghai Province, China, Frontiers in Microbiology, Vol 9 (2018

Feng K; Li W; Guo Z; Duo H; Fu Y; Development of LAMP assays for the molecular detection of taeniid infection in canine in Tibetan rural area, The Journal of veterinary medical science 2017 Dec 22; Vol. 79 (12), pp. 1986-1993

[4] Xu, Y., X. Zhang, and X. Zhu. 2008. Medical financial assistance in rural China: Policy design and implementation. Studies in Health Services Organisation, Strategy and Policy 23: 295–317.