THIRD CCP PLENUM 2024 OPTS FOR BUSINESS AS USUAL

To be Premier of China is a thankless task. Nominally the head of the entire state apparatus, in charge of the executive that plans and implements all policies, the Premier would seem to be one of the most powerful people on the planet.

Yet his (always so far a he) power is eclipsed by the one person above: the General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party. Until recently, China maintained the fiction that, while the CCP determines policy direction, it is the executive that does the detailed planning, based on its close monitoring of everything measurable, then issues “guiding opinions” that are decrees required to be implemented by all levels of government in all provinces.

Under Xi Jinping, that polite fiction fell away, as ruling party and the executive branch overtly fused into a single instrument of power. For years now all laws, regulations and guiding opinions are jointly issued by the CCP and State Council together.

Premiers are meant to keep close watch on ground truths about how folks are travelling, and implement all the Five-Year Plans, regulations and laws. Across 31 provinces and 1.4 billion people, this is no small task, and the executive state is resourced to staff and report, from county level cadres up to prefecture level, then up to the province, then up to the nation-state, and its highest body the State Council, where all Ministers convene.

The Premier is supposed to know how ideology matches up with street level reality, yet has no power to change the ruling ideology when contradictions arise.

Once in a while the Premier and other senior central leaders do manage to speak plainly, identifying those contradictions, state failures, policy errors. But such moments are rare. The most notable such moment was in 2007, when Premier Wen Jiabao, later airbrushed out of official history, bluntly said: “The Chinese economy still has some major problems, namely unstable, unbalanced, uncoordinated and unsustainable problems. The unstable matter is that China has an excessively high investment growth rate, excessively large extension of credit, excessive liquidity of the currency, and improper foreign trade and international payment. China has unbalanced development between urban and rural areas, between different regions, and between economic expansion and social progress, the premier said.” https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/bizchina/2007-03/16/content_829815.htm

Everyone took notice. Even the Bank for International Settlements and International Monetary Fund paid attention. By 2007 it was painfully obvious that inequality was worsening, the rich made enormous fortunes, ethnic minorities were deeply unhappy, factory workers were treated with contempt, the promise that everyone can get rich if they just work hard was contradicted by everyday experienced of precarity, and institutionalised discrimination against the rural poor.

But Wen Jiabao spoke this truth only once, and thereafter toed the line. He had no choice. All central leaders must emanate positive energy, this is mandatory.

Never again have a central leader’s words so closely matched reality. Not until 2024, on the eve of the CCP Third Plenum, scheduled for July 15 to 18, 2024..

On the front page of the official CCP organ, People’s Daily, on 26 June 2024, came a statement uncannily echoing Wen Jiabao: “The problems of unbalanced, uncoordinated and unsustainable development are still prominent, the mode of development is still crude, the development gaps between urban and rural areas and the income distribution gap between residents are still large, social contradictions have increased significantly, there are more problems related to the immediate interests of the masses, the problems of formalism, bureaucracy, hedonism and extravagance are prominent, and the negative and corruptive phenomena are prone to occur more often in some areas.”

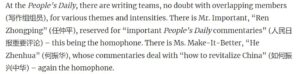

People’s Daily often runs articles meant to be taken as authoritative, from the very highest level, the author nom-de-plumed Ren Zhongping 任仲平but without any doubt speaking for the party-state.[1]

Unlike 2007, this list of multiple failures went almost unnoticed outside China, as it was buried in a standard rendering of Xi Jinping’s brilliant leadership.

Yet it is exceeding rare that the nakedness of the emperor is revealed, not by an innocent child, but by a top-level courtier.

Coming 17 years after Wen Jiabao spoke his powerful truth, this burst of candour is instantly recognised as daily reality. The party-state has become more insulated from reality, more commanding, more demanding, more ideological, more disdainful of the masses, more enamoured of the tech elite and the billionaires. Ethnic minorities on the unassimilated frontiers, Tibetans and Uighurs, recognise the crudeness of state policies that insist on implementation in each province, driven by a command-and-control model that is top down and immune to ground realities.

We don’t know who Ren Zhongping is. But everyone knows the protocol: only the most senior of leaders can take a pseudonym that proclaims him the voice of the people, and of the party-state.

As with Wen Jiabao in 2007, this was an isolated blurt, surrounded by a sycophantic chorus praising Xi Jinping and his unique capacity to steer China to its predestined utopia.

So we could just ignore this, or we could take it as a painfully concise guide to the depth of malaise that afflicts China, much more in 2024 than in 2007.

The official response, from Xi Jinping is that the CCP is on a sacred mission: “Seeking happiness for the Chinese people and rejuvenation for the Chinese nation is the original aspiration and mission of Chinese Communists, and it is the fundamental driving force that inspires Chinese Communists to fight bravely and move forward continuously. On the new journey, we must take staying true to the original aspiration and keeping the mission firmly in mind as an eternal task of party building and a lifelong task for all party members and cadres.” Does anyone in China actually believe this?

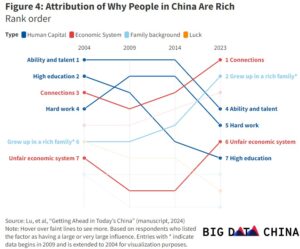

What people do believe is that the system is heavily rigged in favour of the elite, meaning the newly rich and their CCP enablers, and nothing is going to change. Slogans such as “common prosperity” are hollow, at best vague aspirations mouthed occasionally by central leaders, but without substance. The party declares itself in command of the path to an inevitable Marxist utopia, yet fails to finance decent education, health care and social welfare in poor counties, having downshifted responsibilities to local governments.

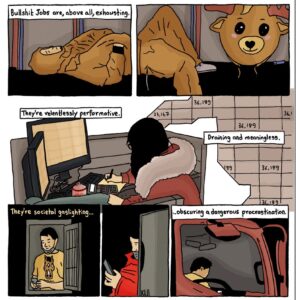

There is ample evidence of widespread disillusion with central leaders whose focus is only on lavishing more and more on the next wave of high tech elites, in the expectation that these “high quality new forces” will save China from its own path dependency on vacuous slogans and mass mobilisation campaigns that waste the energies of those caught in the system. We now have so many accounts, from all over China, of exhaustion, dropping out and lying flat, widespread realisation that relentless competition for the best exam results leads nowhere; that all big corporations are automating and deploying AI to get rid of all but casual workers.

We now have survey data from Harvard sociologists and Stanford economists who measured the depth of ennui, anomie and alienation of the masses. https://bigdatachina.csis.org/is-it-me-or-the-economic-system-changing-evaluations-of-inequality-in-china/

China is in serious trouble, and this will not be patched by utopian rhetoric, nor by stimulus financing of the same old real estate millionaires, nor by yet another round of infrastructure investment in hydro dams, railways and mines in Tibet. Ren Zhongping stated the obvious. China’s contradictions are systemic, structural, and past stimuli no longer work. Diminishing returns.

China is in serious trouble, and this will not be patched by utopian rhetoric, nor by stimulus financing of the same old real estate millionaires, nor by yet another round of infrastructure investment in hydro dams, railways and mines in Tibet. Ren Zhongping stated the obvious. China’s contradictions are systemic, structural, and past stimuli no longer work. Diminishing returns.

The problems are deeper than central leaders can admit. They are high on their own supply of slogans and delusions, while the masses are tired of being treated like chives being slashed whenever the party, for incomprehensible reasons, chooses to slash them, and expect them to regrow, without state help.

There are good reasons to dwell on these wicked problems, which economists call the middle-income trap.

The best reason may be that the world has hardly noticed how deep is the disillusion, or that it will not be airbrushed away with the sloganeering Xi Jinping Thought. Much of China coverage is for investors seeking only short-term profit alerts, with little interest in the longer term. The US Congress and Beltway elite is fixated on China as enemy. China’s think tanks and pundits promote the standard line that one more stimulus push into the free market will correct it all.

Maybe the best reason for understanding the intensity of the contradictions is that Ren Zhongping’s 2024 revival of Wen Jiabao in 2007 matches so closely what people all over China see and say. The match is uncanny. They mirror each other.

This matters especially in the geographies China has sealed off from any outside scrutiny, notably Xinjiang and Tibet. So little light escapes these black holes, they are off just about everyone’s radar. Yet in those rare moments when we do get to hear their anguished voices, they tell us they bear the full brunt of the delusions besetting central leaders blinded by their own ideology. “Social contradictions have increased significantly, there are more problems related to the immediate interests of the masses”, Ren -the voice of the people- tells us. China’s interventions in Tibet are “unbalanced, uncoordinated and unsustainable development are still prominent, the mode of development is still crude”.

From the outset of China’s control in the 1950s, the Tibetans have been consistently misunderstood as a backward, primitive tribe with nothing to offer today’s world. This profound misreading has never been questioned, not even now, 75 years later, in a time when China is quick to depict the US as racist, while utterly blind to its own racist stereotypings.

Nor are China’s leaders open to discovering they have misread the vast lands of the Tibetan Plateau, and its customary stewards. China’s official obsession with “high quality development” conjures into being its polar opposite: low quality. The Tibetans epitomise low quality: backward, stubborn, uncooked, preferring to stay on lands that are unnaturally frigid and dangerously lacking in oxygen, failing to be grateful for China’s modernising interventions, altogether primitive, relying only on the heavens to provide, in every way the opposite of a China that has mastered all technologies and is now the world’s indispensable factory.

From that perspective, the Tibetans are a drag on China’s urgent need to accelerate productivity. At best the Tibetans are a factor of production, but only in low quality unskilled work which all over China, including Xinjiang, is now rapidly being automated. Tibetans can only become minor factors of production if they leave their lands, and are pushed to migrate to where the factors of production congregate, in enclaves of extraction and high tech and high-quality production.

Since the ungrateful Tibetans show little inclination to join the precariat of casual workers, on the lowest rung of a ladder that grows ever higher, they are a security risk. Central leaders are obsessed with security risks, now there is so much to secure in the world’s factory, including secure access to raw critical materials found abundantly in Tibet.

Decades ago, central leaders were persuaded by tendentious misreadings of the dissolution of USSR that a major factor was the nationalisms of the republics of minority ethnicities. For the past two decades, China has solidified its strategy of undoing regional ethnic autonomy, in all but hollow name. Central leaders gaze at Tibet through the lens of securitisation, seeing risks everywhere. This closes any reflective opening to discovering the Tibetans as they are, a subtle civilisation dedicated to realising the nature of the mind.

Ren Zhongping had his 2024 moment, which passed unnoticed. The moment for Tibetans to be recognised as fully human is as far off as ever. Yet his front-page definition of China’s malaise gives us a key to how those statist, nation-building interventions in Tibet manifest, in the lives of Tibetans. When the emperor, in far distant Beijing, decrees unbalanced, uncoordinated and unsustainable development projects in Tibet, decade after decade, how does that look, on the ground, through Tibetan eyes? When a developmentalist state designs and constructs its alien rule power projections deep into high plateau landscapes, yet the mode of development is still crude, how do Tibetans experience the nation-state’s agenda? What does unbalanced development, wrapped in indecipherable slogans, formalism, bureaucracy, hedonism and extravagance actually look like, at ground level? Wen Jiabao and Ren Zhongping have gifted us these key words; now we can see how they play out.

The 3,358,394 Tibetan pastoralists herded off their lands this century and into distant villages under constant surveillance have had direct experience of the crudely coercive methods of cadres implementing policies which all have as their objective disempowerment and displacement of independent livestock producers, reducing them to dependence on ration handouts. Human Rights Watch in May 2024 listed the many incomprehensible policies deployed to justify state enclosure of the commons, and expulsion of the stewards of sustainable landscapes.

HRW’s “Educate the Masses to Change Their Minds”: China’s Forced Relocation of Rural Tibetans lists (Appendix 1) lists the jargon of unbalanced, uncoordinated and unsustainable development, all promising a better future of prosperity if pastoralists accept an offer they are not permitted to refuse. This is done in the name of ecological migration away from degrading landscapes, alleviation of poverty in counties designated as contiguously and chronically poverty stricken, extremely high altitude relocation, compulsory sedentarisation on winter grazing land, Construction of Well-off Villages in the Border Area, The Sa-ngen Cross-municipality Whole-village Relocation Program, “Rangeland Construction and Pastoralist Sedentarisation”, “Natural Forest Relocation” program.

If these seem unclear in English, they are just as vague in Chinese, and if translated into Tibetan, for official use, incomprehensible. In the name of watershed protection, carbon capture, resolving the contradiction between grass and animals, prosperity and development millions of Tibetans have been dispossessed of the lands they curated skilfully for thousands of years.

What has changed is that Tibetans and Uighurs are no longer alone in being alienated from a party-state that demands loyalty but delivers only slogans, not respect for citizens and their daily struggle.

The party-state boasts it is at the forefront of fast patriotic response when disasters -earthquakes or floods- suddenly strike. Official propaganda urges the masses to donate to disaster relief efforts of official NGOs under party-state control. But the widespread floods of July 2024 generated a very different popular response, evident in social media posts in Chinese: “When trust is betrayed time and again, and appeals for charitable donations remind potential donors of past fundraising abuses, the trust and attention of the public will, much like the floodwaters, gradually ebb. The mocking comments we see online are more than an expression of dissatisfaction; they are a barometer of what the general public has come to expect. It is essential that we pay attention not only to the catastrophic flooding, but also to this crisis of public trust. Natural disasters may destroy homes, but the collapse of public trust is even more deadly. Floods may carry away the soil and inundate cities, but they cannot wash away human kindness. The sympathy and trust of the public is a scarce and precious resource. Once this trust is lost, it will be very difficult to rebuild.”

***************************

Given the systemic slowing of an economy whose past growth legitimated party-state hegemony, one might expect the ruling party to face up to the deep problems of relying on endless growth, ignoring the climate change slogan of reduce, reuse, recycle. This is an entrenched ruling party proud of its ability to forge new eras, in accord with laws of history and development, uniquely capable of seizing opportunities, reading the changes not seen in a century, discerning and delivering the correct line as circumstances change.

The Third Plenum of the Chinese Communist Party Central Committee is specifically the forum for making long term economic policy change, based on top-level design. The Third Plenum of 1978 was the moment China abandoned Maoism and embraced the market. It was at the 2013 Third Plenum that Xi Jinping came to full power, in charge of everything.

Yet all China watcher predictions of the 2024 Third Plenum see little sign of any of the redistribution of wealth to consumers, that would stimulate growth, and fulfil the core promise of socialism. Atlantic Council: “This strategy will offer little respite to a population struggling to make ends meet and businesses that have lost the will, or means, to invest. Beijing’s drive for what it calls a “high-level socialist market economy” based on “new quality productive forces” will be powered by Xi’s willingness to see the Chinese people—especially its young people—“eat bitterness” in pursuit of national ideals. Government resources are being directed to research and development and industrial subsidies, not social programs.”

Asia Society: “The policy signals for this month’s plenum suggest a strong emphasis on Xi’s goals of achieving technological self-reliance, addressing financial risks, streamlining central-local relations, and improving social welfare. Policymaking at the 20th Third Plenum will follow more of a political logic than an economic logic. Xi reforms aim to “advance the modernization of China’s governance system and capacity” writ large, a theme articulated at the 2013 and 2019 plenums. His top goal for this plenum is not to revive growth but to continue his political project.”

Chatham House: “Expect further government intervention to channel economic resources into the strategic and innovation sectors and to guarantee minimum social welfare to the poor. These are unlikely to be policies eagerly waited and favoured by private enterprises and global investors. From now on, the ultimate goal is to make China a champion of innovation through generating disruptive technology and scaling up into high-end manufacturing. Previous industrial policies mostly focused on expanding global market share for China’s own exports. This new term calls for the government and enterprises to lead future industries that are in the nascent stage at a global level. The second and related new vocabulary in this upcoming plenum is ‘new national system’. This refers to distributing national resources with an even stronger centralized control, allocating capital to sectors with strategic significance. The underlying emphasis here is not on the economy but on geopolitics.”

Social welfare does rate a mention, not as the core strategy to stimulate a consumption-led economy, but as a token slogan with limited substance. No sign hukou will be abolished, or transfer payments to the poor and disempowered will rise, or that workers will be free to make their own trade unions. China is doubling down on enhancing the power of the imperial court, its embrace of science and technology as the solution to every problem. China is becoming more elitist, despite the vague rhetoric of “common prosperity.”

Expect coverage of this CCP Third Plenum to be muddy. Chinese media will proclaim it an all-round triumph, including the “common prosperity” slogans without substance. Western analysts will focus on China’s intensifying subsidies to the high-tech industries that are expected to magically rescue China from its slump. They will emphasize subsidies that result in over production of manufactures that must be exported, since consumer demand will continue to be held back by poverty, gig work precarity, and the necessity of saving rather than spending, since doctors, hospitals, schools, aged care are so expensive.

[1] David Gitter and Leah Fang, The Chinese Communist Party’s Use of Homophonous Pen Names, Asia Policy, Vol. 13, No. 1 (JANUARY 2018), pp. 69-112