A Tibetan new gen in exile has opportunity to revitalise the Tibet issue, to make it integral to the many global debates already trending.

Existing debates about climate, carbon emissions, air pollution, pandemic response, wildlife extinctions, inequality, entrenched racism, now dominate the public sphere worldwide.

These debates lack Tibetan voices, who could offer uniquely Tibetan perspectives on the issues of the day. These are the issues of greatest concern both to governing elites and the people.

Tibetans can show they do have a unique voice, a fresh angle, a viewpoint that enables things to be said that others can’t say. When the US critiques China, it is readily dismissed as a bully insisting on its exclusive right to behave badly, while denying China the same right. However, when Tibetans talk about accelerating climate change, loss of biodiversity, systemic racism, extreme inequality they speak from a position of displacement, marginalisation, disempowerment. They speak from the experience of being held in racist contempt by Chinese power, in a time when the whole world now struggles to understand and re-assess China’s intentions.

Everyone worldwide needs to grow their ability to decode the incomprehensible jargon of China’s rise. Tibetans, inheriting thousands of years as neighbour of China’s imperialism, have the insight, know how to read between the lines. Educated new gen Tibetans, speaking up confidently on these issues will find themselves heard, as guides to how to understand what China really intends and plans.

Language is the key. China’s power is not only military, it is discourse power, the power to define the memes everyone lives within. China is ruled by mass campaigns, and the mass campaigns are run by slogans, official phrases endlessly repeated, propaganda calculated to confuse and lull, while mobilising cadres to take command.

One key to growing Tibetan confidence in contributing to the great debates of our times is to sharpen our ability to unpack and decode China’s key propaganda slogans. Once we are able to discern the long term thrust of China’s central leaders, we give ourselves the tools we need to then enlighten others, worldwide.

Right now China’s key terms are opaque, incomprehensible. The more these deliberately vague phrases are repeated in official Chinese media, the more meaningless they become. Inside Tibet, an army of educated Tibetans is required, day after day, to translate these official campaign slogans into Tibetan, and they must use officially authorised Tibetan phrases. They find this endless cut & paste meaningless, leaving them with little idea of what is really meant, what China has actually planned for Tibet. This is not only boring, alienating and bewildering for Tibetan intellectuals, it leaves their readers uninformed. The rigid governance of CCP jargon in Tibetan translation perpetuates the gulf between ruler and ruled, leaving Tibetans who watch official TV or read official media, whether in Tibetan or Chinese, none the wiser. This is disempowering, and exacerbates mistrust.

So getting a handle on CCP jargon:

- helps exiled Tibetans help themselves,

- helps Tibetans inside Tibet,

- helps a wider world frustrated by the opaqueness of China’s vague and plausible sounding rhetoric.

China scholar Nadege Rolland, 2020: “Whoever rules the words rules the world. It is China’s turn, as the ascending great power about to surpass all others, to assert authority over the world order using the same instruments that the West has used to establish and maintain its dominance.”

EIGHT KEY CHINESE SLOGANS ON CLIMATE & TIBETAN LIVELIHOODS, UNPACKED AND DECODED

COMMON BUT DIFFERENTIATED RESPONSIBILITIES

UN CONVENTION ON BIODIVERSITY

NATIONAL PARKS

SANJIANGYUAN

GRAIN TO GREEN

CONTIGUOUS DESTITUTE AREAS

RELYING ON HEAVEN

BUILDING A SKY RIVER

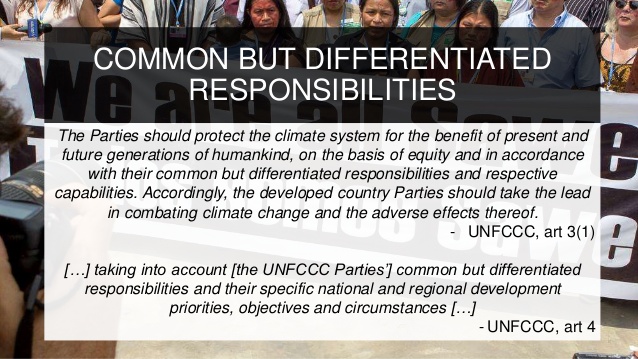

1: COMMON BUT DIFFERENTIATED RESPONSIBILITIES 关共同但有区别的责任概念的最 Guān gòngtóng dàn yǒu qūbié de zérèn gàiniàn de zuì, ཐུན་མོང་ཡིན་ལ་དབྱེ་བ་ཡང་ཡོད་པའི་འགན་འཁྲིའི་རྩ་དོན།

This vague and seemingly innocuous phrase is a heavily laden pack yak in much need of unpacking. What China means is that it is exempt from global standards, global agreements, and international law. China is to be judged only by China’s unique standards, and the definition of those uniquely Chinese characteristics is solely in the hands of the CCP.

China has been pressing for this key phrase to be inserted into the language of many UN agencies and agreements, as proof of China’s rise, and impunity. It is firmly embedded in the wording of the UN Climate Convention.

In the global climate debate, it means China, despite being the world’s biggest polluter and carbon emitter, has less responsibility to reduce emissions, because other countries have been emitting for longer. In fact, it means China need not commit to any specific reductions in carbon emissions at all, unlike almost all other countries. China’s only “voluntary national contribution” to reduce emissions is to reduce emissions per RMB unit of production. That does not add up to any actual emissions reduction at all, and China has explicitly said it will not begin emissions reduction until 2030.

The 2015 Paris agreement was so weak, it left it up to each signatory to nominate its own target, and China nominated this calculated measure of efficiency, not an actual tonnage emissions reduction at all.

China insists on being different, and on being assessed solely on its own terms. This diplomatically vague formula originated way back in 1972, in the very first effort to bring the world together to tackle environmental issues. The Stockholm conference of 1972 started it all, at a time the Cultural Revolution raged in China, and no-one could possibly imagine China could become the world factory and world’s biggest polluter. Fifty years ago, “common but differentiated responsibilities” did mean the richest countries, with the biggest environmental impacts, had greater responsibility. China has rigidly insisted ever since that this is still true.

China’s differentiated, lesser responsibility to solve the climate crisis further means China, as a developing, not developed, economy, has the right to demand of the richest nations that they pay for China’s climate mitigation. China’s official position is that: “the financial supports from developed countries are not enough to close the finance gap of China to address climate change. From 2016 to 2030, besides the inputs of domestic public and private sectors, China will additionally need an average of 1.3 trillion yuan annually.”

If paid from 2020 to 2030, that’s RMB 13 trillion, US$1824 billion. Clearly there is no intention anywhere to subsidise China’s climate adaptation along those lines, so China can let itself off the hook, blame others, and continue to delay doing anything meaningful.

China’s refusal to shift in 50 years, beyond its exceptional exemption from actual climate action, could doom life on this planet. China is not the only climate change denier, but it is the biggest, and as a planet, time is running out to adapt before climate change accelerates into an unstoppable momentum, completely beyond our control.

2: UN CONVENTION ON BIODIVERSITY

Wildlife trafficking to China, to feed Chinese appetites for exotic meals and exotic sources of traditional medicine, is the likeliest cause of the global corona virus pandemic. China’s demand for wildlife consumption reaches into countries worldwide, driven by demand for rhino horn, elephant tusk, pangolin scales, shark fins and myriad other animal parts, plus whole animals smuggled alive to China and kept alive, in the wet markets where the corona virus jumped across to humans.

Despite this appalling record, China loudly proclaims its deep love of wildlife, and is now legislating to outlaw eating wildlife, as it has done before, with little effect. However, in the fine print of the 2020 law is an exemption for TCM use, for the supply of dried animal parts for use in Traditional Chinese Medicine, which has been strongly promoted during the Covid-19 pandemic as effective treatment, with Chinese characteristics. Not only is TCM use exempt, so too is the “farming” of wildlife in cruelly small cages, for painful extraction of bile, or for slaughter to meet the TCM demand.

Given this long-standing scandal, China is determined to regain discourse power by proclaiming its strict protection of wildlife, not in lowland China but in upland Tibet.

China regains legitimacy by giving its new law on wildlife strong language, even in its title: Decision on Comprehensively Prohibiting the Bad Habits of Eating Wild Animals, and Effectively Safeguarding the People’s Health and Safety, 关于全面禁止非法野生动物交易、革除滥食野生动物陋习、切实保障人民群众生命健康安全的决定 ཁྲིམས་འགལ་ངང་བདག་ཏུ་མ་བཟུང་བའི་སྲོག་ཆགས་ཉོ་ཚོང་བྱ་རྒྱུ་གཏན་འགོག་དང་། བདག་ཏུ་མ་བཟུང་བའི་སྲོག་ཆགས་གང་བྱུང་དུ་ཟ་བའི་སྲོལ་ངན་མེད་པར་བཟོ་རྒྱུ། མི་དམངས་མང་ཚོགས་ཀྱི་ཚེ་སྲོག་བདེ་ཐང་འགན་ལེན་ཏན་ཏིག་བྱ་རྒྱུ་བཅས་པའི་སྐོར་གྱི་གཏན་འབེབས།

China’s long-term strategy is to not only regain legitimacy but, yet again, claim world leadership in wildlife protection, and Tibet is the core of this plan. That is why the launch of the new national park system has been years in the making, involving elaborate governmentality mechanisms, and a new discourse, studded with campaign slogans.

China’s new commitment to wildlife protection in Tibet naturalises several concepts such as carrying capacity, carbon capture, degradation repair, grain to green, core and buffer zones, red line exclusion zones, all of which need decoding, with due diligence done on the fine print.

Tibet is meant to save China, and position it as a world leader in biodiversity conservation. The crowning moments, scheduled for 2020, probably now postponed because of the virus crisis, are the launch of the national parks, and the staging of the Conference of the parties to the UN Convention on Biodiversity, scheduled for Yunnan Kunming in late October 2020.

3: NATIONAL PARKS 国家公园 Guójiā gōngyuán

While China, under the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities, excuses itself from doing anything much to reduce its climate warming emissions, it wins back its lost reputation by zoning as much as 30% of the entire Tibetan Plateau as national parks. 2020 has been designated as the launch year for the new park system which, by area, is overwhelmingly in Tibet.

Who could possibly object to a national park? Especially in Tibet, where the alternative in recent decades has been predatory mining, rapacious slaughter of wildlife, state construction of hydro dams and power grids.

But do the new national parks include the many Tibetans whose pastures are to become nationalised parks? Does zoning huge landscapes as ecological effectively exclude customary land use, and users? Does the fine print of the “top-level design” of the national parks halt mining, hydro damming, power grid construction and other enclaves of intensive industrialisation, including yak feedlots and large-scale slaughterhouses?

photo: Kyle Obermann

https://supchina.com/2020/05/01/conservation-china-nomads-and-the-yellow-river-king/

We need to look beyond the slogans to realities on the ground. So far, all indications are that national parks will further displace and disempower Tibetan nomads into destitution, while employing a few to police the rest.

National parks are meant to be protected areas. But many familiar concepts, when they acquire “Chinese characteristics”, morph into something else. For example, the UNESCO World Heritage Three Parallel Rivers area in Tibet, where the Yangtze, Mekong and Salween Rivers run in close parallel, was drawn by China to exclude the actual rivers, and include only the steep valleys filled with medicinal herbs. The rivers can and are being hydro dammed, and UNESCO is firmly told to mind its own business.

mgar nyang chen byang chub chos gling, now part of Sanjiangyuan

4: Sanjiangyuan, གཙང་གསུམ་འབྱུང་ཡུལ།༼རྨ་འབྲི་རྫ་གསུམ་འབྱུང་ཡུལ།༽ 三江源, literally Three River Source, a newly invented term in Chinese for the sources of the Ma Chu (Yellow), Dri Chu (Yangtze) and Za Chu (Mekong), all originating in Tibet. Because this is a new word, there is no equivalent in Tibetan, only a transliteration that sounds roughly like the Chinese neologism.

Sanjiangyuan is misleading in a few ways. It obliterates situated Tibetan district place names, histories and identities across two entire prefectures, Yushu and Golok, plus other counties, 15 altogether, all swallowed by one word.

This single term naturalises a huge landscape, the size of Germany, defining it by what it provides to lowland China, reducing complexity to a single function: water flow. By erasing the attributes of hundreds of grazing landscapes, reducing them all to water provisioning, the entire territorialised and officially zoned Sanjiangyuan no longer faces west towards the rest of Tibet, but east towards lowland China.

Sanjiangyuan is misleading also in referring only to sources, high in the glaciers. In reality these braided rivers meander across the gently tilted plateau for at least one thousand kms, before plunging into steep valleys as wild mountain rivers full of energy China is keen to harness by building hydro dams athwart all three. Sanjiangyuan appropriates myriad situated local meanings and knowledges, bundling all into a new package defined solely by its service to the lowlands below. The focus on single point sources, at the feet of glaciers, evokes imaginaries if purity, connecting urban lowland Chinese with pristine mountain springs; so the vast intervening pastures, with cattle shitting everywhere, becomes by definition problematic.

Classically, China was happy to imagine the Yellow River rises in the heavens, as in this 8th century poem by Li Bai: 黃河之水天上來 huánghé zhī shuǐ tiān shànglái, the waters of the Yellow River come from upon Heaven. This famous line is now requoted in Qinghai Scitech Weekly (27 May 2020) under the heading Popularising Science of the Yellow River Source, 大河开启生命之源 ཆུ་བོ་ཆེན་པོ་ཡིས་ཚེ་སྲོག་གི་མགོ་བརྩམས་པ་རེད།

Now the Yellow River’s many sources are all precisely georeferenced, monitored by remote sensing satellite cameras, memorialised by official monuments proclaiming China’s Tibet.

To Western audiences China’s mixture of rhapsodic romanticism and scientific data-driven rhetoric sit oddly. But today’s China embraces both, seeing no problem.

In official media, China’s new enthusiasm for governance of Tibetan landscapes and watersheds is frequently wrapped in romantic Shangri-la metaphors that are extravagant even by the standards of 19th century European explorers.

The same Qinghai Scitech Weekly article has many other lyrical phrases proclaiming China’s ownership:

The countless lakes are like stars in the sky, displaying exotic scenery, colorful as a painter’s palette, 黄河源头的星星海,由大大小小难以数清的湖泊、海子、水泊所组成,无数湖泊宛如天上繁, 呈现出奇异景色,色彩斑斓似调色板。据中新社

The Yellow River spends all day and night, flowing endlessly, nourishing all creatures, and is the mother river of the Chinese nation. This big river resembling a dragon has given birth to Chinese civilization and has been endowed with so many cultural and spiritual symbolic meanings. 黄河不舍昼夜,川流不息,滋养万物生灵,是中华民族的母亲河。这条形似巨龙的大河因为孕育了中华文明,被赋予了太多文化和精神上的象征含义。Huánghé bù shě zhòuyè, chuānliúbùxī, zīyǎng wànwù shēnglíng, shì zhōnghuá mínzú de mǔqīn hé. Zhè tiáo xíngsì jù lóng de dàhé yīnwèi yùnyùle zhōnghuá wénmíng, bèi fùyǔle tài duō wénhuà hé jīngshén shàng de xiàngzhēng hányì.

This Sinocentric orientalism is now typical, very common, especially in tourism marketing. This is the language that transforms Tibet, from Tibetan landscapes with deep backstories, into China’s jewel, China’s Tibet.

5: Returning non-productive cultivated farmlands to forests, རྨོ་བསྐྱུར་ནགས་གསོ། 退耕还林 tuigeng huanlin, sometimes in English known as the Sloping Land Conversion Program (SLCP), a policy premised on reversing earlier policy. In the name of each province maintaining self-sufficiency in food security, steep slopes had been cleared of forest, from the 1950s through to the 1980s, and this was now wrong. The farmers eking a living on upslopes were dryland farmers with little access to water. Ploughing slopes, baring the soil, led to erosion. However this 1990s policy was implemented all over China on a one-size-fits-all model imposed from above. In Tibet, it often meant farmers had to abandon farms, or turn much of their allocated land to plantations of designated tree species, with much loss of income. Destitution was averted official transfer of survival rations. SLCP was popularly known as grain to green. Officially the preferred green was forest, but much of Tibet is not forest but grassland, and much of the pasture land slowly expanded over many centuries, by pastoralists inhibiting the regrowth of shrubland and forest in their pastures.

This historic expansion of grassland was done sustainably, with no evidence of wildlife extinctions. None of this was understood or acknowledged by the national SLCP project, which continued for decades.

In eastern Tibet (Kham) thickly forested old growth forests were intensively logged for decades, until mid-Yangtze floods attributable to excess runoff from Kham of monsoon rains led to a sudden logging ban in 1998. SLCP and the logging ban happened at the same time, so SLCP could have been used to employ the former woodcutters, many of them Tibetans employed by local state owned resource extraction companies, to do the labour intensive work of seeding and planting seedlings to restore forest. This did not happen. Some Chinese state employed timber workers, unemployed because of the logging ban, were redeployed to do aerial seeding, scattering seeds collected by cutting down remaining trees for seed stock. This too was not successful, as seedlings on steep, bare slopes in alpine climates need labour-intensive protection. Without protection from mature trees, a sheltering canopy, seedlings die in the sharp frosts. To survive, they need human hands, not just seeds dropped from airplanes.

Nonetheless academic assessments of SLCP across China have generally rated it a success.

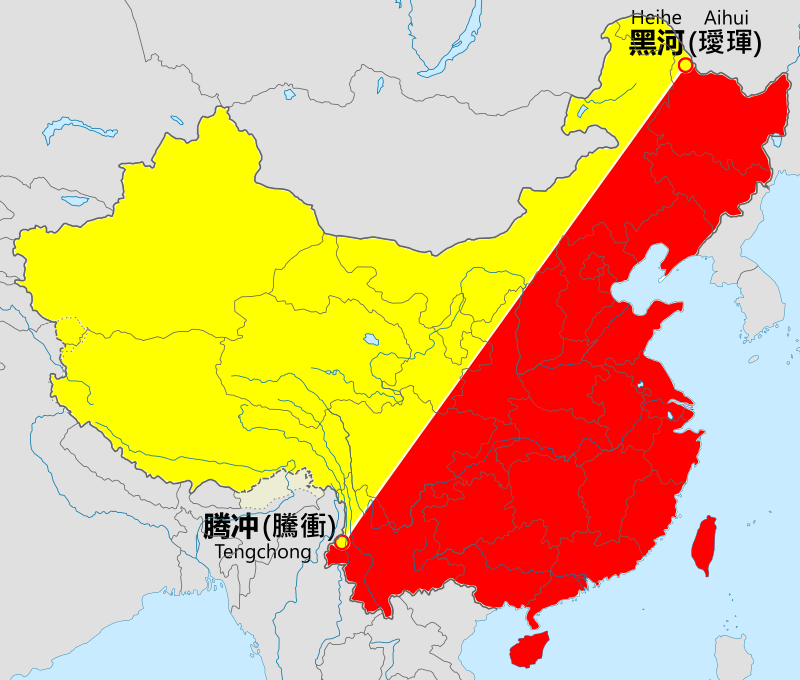

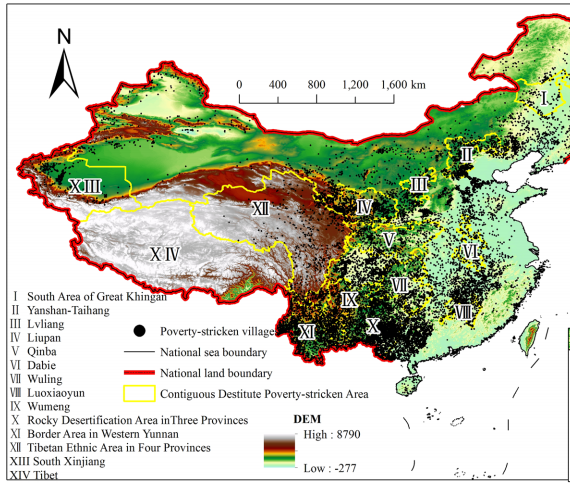

6: Contiguous destitute areas གཅིག་བསྡུས་ཡུག་སྦྲེལ་གྱི་དམིགས་བསལ་དཀའ་ངལ་ཡོད་པའི་ས་ཁུལ། 个集中连片特困区贫困 Gè jízhōng lián piàn tèkùn qū pínkùn, This is a concept that attempts to explain why past poverty alleviation projects have failed, by blaming the land and the people of those landscapes. It attributes cash income poverty to inherent characteristics of territory; in Tibet this means the combination of altitude, hypoxia and extreme weather. This is a thoroughly lowland Chinese imaginary, which assumes no-one would choose to live in Tibet, if they had a choice. Tibet, in lowland eyes, is unnaturally and dangerously cold, and the air so thin each breath threatens to be your last. Territorial mapping depicts counties officially designated as poor, adjacent to counties with the same status. This adds up to contiguous destitution. Thus defined, the obvious solution is to remove the population to somewhere more congenial, and better endowed with the factors of production. By removing people from areas no-one would choose, you do them a favour, and they should be grateful.

7: Relying on heaven རྨ་ཆུ་བསྲུངས་ཏེ་གནམ་ལ་བརྟེན་ནས་འཚོ་ཐབས་བྱེད་པའི་ཉིན་མོ་དང་ཁ་གྱེས་པ། 告别了守着黄河靠天吃饭的日子, gàobiéle shǒuzhe huánghé kào tiān chīfàn de rìzi. literally: passively watching the river slide by without extraction, passively reliant on what the heavens provide. This is the fate of backward, uncivilised and/or lazy people who passively wait for nature to produce all that is needful in life, to be gathered in season. In Chinese eyes, this gatherer lifeworld is little better than that of animals, and fails to show mastery of nature.

China is deeply ambivalent about nature, believing both in harmony and in mastery, both protection and conquest. Ancient traditions of living harmoniously with nature are making a comeback, but the core promise of the CCP is to deliver moderate prosperity for all, in a highly urbanised, densely populated consumer society.

This unresolved tension plays out geographically, with upland western China, especially the Tibetan Plateau, designated under zoning laws as areas of restricted human carry capacity where landscapes and wildlife are to be protected; while the same standards do not apply to the densely packed lowlands of southern and eastern China, where the human footprint is fourfold in excess of the capacity of the land to support the human population.

8: Building a sky river དགུ་ཚིགས་བཟོ་སྐྲུན།, 天河工程 Tiānhé gōngchéng,seeding Tibetan clouds with chemicals to force rain into China’s rivers, a bonus enhancement of the rain made to fall within the catchment of the Yellow River, which in the lowlands is so overused and abused that in many winters it dries up altogether and fails to reach the sea.

In many countries, cloud seeding with silver iodide burning on the wingtips of airplanes flying into the clouds, has been tried experimentally, with at best inconclusive results. This failure has not deterred China’s tech enthusiasts, who claim to have found a way of scattering liquidised silver iodide into Tibetan clouds, without the expense and personnel of having to fly airplanes stationed on the ground, ready to take to the air at short notice.

China’s preferred tech is rockets fired at the sky, from batteries on the ground, activated by China’s necklace of Beidou satellites orbiting above Tibet, measuring the clouds. The whole operation could be automated, driven by algorithms.

Not only is there no evidence this would work, if it did succeed, it would only deprive inner Asian landscapes even further from any ocean of much needed rain. More rain over the uppermost Yellow River would mean less precipitation in the Hoh Xil (Achen Ganggyab in Tibetan) UNESCO World Heritage area, which China lobbied for in 2017. China is now obligated to do all it can to protect this land of lakes that is Hoh Xil, not deprive an alpine desert of the little rain it gets.