HAN SELF-RIGHTEOUS RAGE IN XINJIANG

TWO of four blogposts on authoritarian China’s delusional fixation on predictive policing

CITIZENS ARE THE PREDICTABLE ENEMY

In China, this quest to identify the enemy has deep roots. It is almost 100 years since Mao wrote one of his most famous essays: “Who are our enemies, and who are our friends?” A more recent book, Policing Chinese Politics: a history, reminds us the figure of the enemy is what binds China now, and “tells the story of what happens when the binary of politics saturates the life world to become its doxa- when every facet of life turns on knowing who the enemy is and acting against that figure. It is at that moment that we arrive at that point when society and life become fused in politics.”[1]

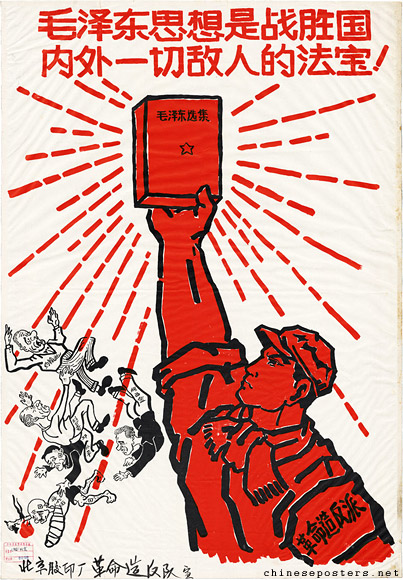

Mao’s obsession became China’s obsession. Mao was formulaic. There was always an enemy, no matter how much revolutionary violence had just named, struggled and purged them. But the enemy was always small enough to be opposed, isolated and defeated. Usually, and by definition, the enemy was five per cent, big enough to be a threat, small enough to be dealt with, leaving the remaining 95 per cent the overwhelming supermajority of us, constituting a universe of fellow feeling, a nation united against the enemy. Us always greatly outnumbered them.

The Uighurs however, by their refusal to assimilate, had shown themselves to be recalcitrant, resistant to both push and pull, both to incentives to transfer loyalty to the state, and to punishment. The problem had become extremely serious, and it was up to big data and predictive policing to determine who the bad actors are. The outcome was 10 to 15 per cent of all Uighurs required coercive rectification. It is not hard to imagine China coming to similar conclusions about the Tibetans, but so far China’s turn, yet again, to严打 yanda, strike hard, has fallen harder on the Uighurs.

WALLS OF COPPER AND IRON

Xi Jinping’s tour of Xinjiang in 2014 signalled a major turning. His secret speeches to Xinjiang cadres became public years later: “The methods that our comrades have at hand are too primitive,” Mr. Xi said in one talk, after inspecting a counterterrorism police squad in Urumqi. “None of these weapons is any answer for their big machete blades, axe heads and cold steel weapons. We must be as harsh as them,” he added, “and show absolutely no mercy.” In free-flowing monologues in Xinjiang and at a subsequent leadership conference on Xinjiang policy in Beijing, Mr. Xi is recorded thinking through what he called a crucial national security issue and laying out his ideas for a “people’s war” in the region.

“Although he did not order mass detentions in these speeches, he called on the party to unleash the tools of “dictatorship” to eradicate radical Islam in Xinjiang. He likened Islamic extremism alternately to a virus-like contagion and a dangerously addictive drug, and declared that addressing it would require “a period of painful, interventionary treatment….. The psychological impact of extremist religious thought on people must never be underestimated,” Mr. Xi told officials in Urumqi on April 30, 2014, the final day of his trip to Xinjiang. “People who are captured by religious extremism — male or female, old or young — have their consciences destroyed, lose their humanity and murder without blinking an eye.” In another speech, at the leadership conclave in Beijing a month later, he warned of “the toxicity of religious extremism………As soon as you believe in it,” he said, “it’s like taking a drug, and you lose your sense, go crazy and will do anything.”[2]

This is Han China’s own orientalism, its’ meme of the Islamic fanatic, taking us back to Marco Polo’s hashish fuelled assassins, who will murder you in a flash.

Xi Jinping vowed China will build in Xinjiang “walls of copper and iron” 铁壁铜墙 tiě bì tóng qiáng, a metaphor stretching back to the Mongol Yuan dynasty that ruled China in the 13th century. It’s a poetic way of saying adamantine, indestructible, eternal; perhaps akin to Donald Trump’s wall to forever keep Latinx fenced out.

Xi Jinping’s other key metaphor was a pledge to build nets reaching to the sky 蚊帐从地球传播到天空 Wénzhàng cóng dìqiú chuánbò dào tiānkōng. At the time, in 2014, it was not obvious what he meant. Was it a giant mosquito net to protect the body politic from infection? In 2014 it was hard to visualise what a net reaching to the sky, through which all Uighurs would be sieved, would look like. Now we know. In retrospect, it’s an apt image of the hi-tech surveillance state forever gazing remotely at the lives of all Uighurs, with predictive policing netting those classified as unreliable, for correction.

Aided by the algorithms of predictive policing, mass incarceration has become a huge experiment in brainwashing, possible as long as the proportion of the total population at risk is not more than 10 or perhaps 15 per cent. Detainees do mandatory performative repetition of official slogans. Party-state officials hope this will not only wear away their stubborn resistance to assimilation, it will also convince the rest of the population to identify with the unitary nation-state and its single, unitary race-nation, the zhonghua minzu. Thus, it becomes, yet again, a “people’s war” against the minority and their errant thinking. “We must launch an anti-terrorism and stability maintenance People’s War, encourage the masses to offer and report evidence of terrorism, and support the people and the masses, in conjunction with the armed forces to subdue and arrest thugs.”[3]

A “people’s war” deliberately invokes memories of Mao’s declared war strategy when, as expected, the Americans would invade. Mao’s strategy was to allow the enemy deep inland, at enormous human cost, then surround and eliminate the invaders, in a scaled-up version of how Stalin’s Soviet Union defeated Hitler’s armies. For a people’s war to work, it must be absolutely clear to all who “the people” are. When dealing with the expected foreign invasion, that is easy; when the enemy to be subdued are citizens, of a minority nationality guaranteed autonomy by law, not so easy.

HAN WAVES

In practice, mobilising the Han against the Uighurs has worked, making it clear who wages people’s war, against whom. The populating of Xinjiang by Han is a major reason why the situation in Xinjiang now is so much worse than in Tibet, where emigration of Han into Tibet remains constricted.

Yet this mobilisation of the Han took time, in fact decades. This is because -unlike Tibet- the number of Han who emigrated to Xinjiang is large, yet they came in distinct waves, with distinct differences in attitude towards the Uighurs.

Today in Xinjiang, Mao’s 1920s question: Who is our enemy? Who is our friend? is readily answered. But it was not always so straightforward. The first wave of Han emigrating to Xinjiang in the 1950s and 1960s were themselves a minority, often ordered to the frontier as demobilised soldiers to be kept well away from the capital in case they fomented trouble. They were organised into a paramilitary production brigade, known in English as the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (XPCC) and in Chinese simple as the bingtuan. They had the dual function of repressing the Uighurs should they revolt, and of building large scale state farms, highways and infrastructure. This encouraged other Han to migrate, to work in the oil extraction industry, cotton, melon and grape farming, their produce in demand in eastern China.

The bingtuan became a full-scale military industrial complex, dominating many industries, providing cradle to grave iron rice bowl security to its employees. The bingtuan issues its own statistical yearbook, as provinces do. The 2018 bingtuan yearbook lists the number of people within it as just over three million, of whom 2.55 million are Han.

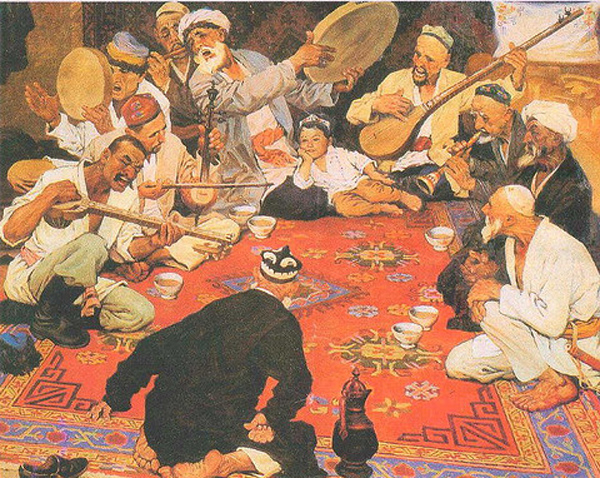

Despite the military structure of the XPCC, this first wave was acutely aware that Xinjiang is huge, the Uighurs at every turn made it clear it is their home, and the Han could in no way ignore the traditional land owners. Gradually, as the decades passed, a modus vivendi evolved. Uighurs and Han socialised to some extent, learned each other’s languages a bit, and above all, discovered each other’s favourite foods. A limited multiculturalism grew.

The second wave came from the mid-1990s onward, incentivised to emigrate by official propaganda, subsidies, investment capital from Beijing, into the existing Han enclaves of northern Xinjiang. New industries grew: oil extraction became gas wells and coal mines and power grids and aluminium smelters and scaled up agricultural commodity production for distant Chinese markets. Xinjiang is China’s Belt and Road gateway to the extraction of resources across central Asia, and the Belt and Road Initiative rapidly globalised Xinjiang and renewed Han migration, sped up by faster railways and highways. This second wave had less time to acculturate, to get to know Uighurs socially, and less reason to do so, as Uighur resentment at being overwhelmed and treated with racist contempt hardened everyone. The second wave was more hard-headed than the first, less inclined to accommodate difference, more certain of China’s civilising mission, at a time of China’s rapidly growing wealth.

HAN MOBILISE FOR A PEOPLE’S WAR AGAINST THE PEOPLE

When resentments flared into violence, socialising ceased. Battle lines were drawn, people’s war against Uighur “extremists” declared.

The people’s war did require mobilising all Han in Xinjiang, whether first or second wave. Features of the new people’s war were extraordinarily labour intensive, requiring every Han to report for duty. It is this enlistment of all Han in Xinjiang, reconstituting them as the people/volk/ethnos/zhonghua minzu of people’s war against the people’s enemies, that is the most unique aspect of the Xinjiang strike hard campaign. It has no historic parallel, but it does, as with much else in Xinjiang, have precedents in Tibet.

In the earlier phase of mass Han mobilisation, the core task was to define who is the enemy. Since the Xinjiang Han and Uighur populations are roughly the same in numbers, it would be impossible to classify all Uighurs as enemies, even though the Han coalesced around a single phrase: “The Uighurs are so bad”. The enemy, whether five or ten or 15 percent or even more, had to be identified, at a time when facial recognition software and the algorithms of predictive policing were still being developed.

The party-state did what only a highly authoritarian party-state could do, there is little precedent elsewhere, other than in Tibet. Politically reliable Han were ordered to live with Uighur families, under one roof, sometimes for a week at a time, sometimes longer, often repeatedly, and then report their data to the security state’s fast expanding big data aggregations. Uighur families were ordered to accept these projections of party-state power into the hearth, living space and bedrooms of all Uighur, knowing full well they were being assessed as trustworthy, unreliable, or enemy.

This requires, of all Han, an unshakeable conviction in their civilisational superiority, a manifest destiny as tutors to the poor and backward, a strong belief that this invasion is for the good of all.

For Uighurs, it requires displays of gratitude, from the moment the Han invigilator arrives, showing him (sometimes her) to the best room, to be served the best food and, above all, to perform the declamation of official slogans, not just when prompted, but at all times.

Everyone knew this was crunch time; that lifeways would be decided by these assessments and reports back to the burgeoning big data, for the algorithms to do the crunching. And everyone knew that everyone had to act as if this was normal, and in fact welcome. Any slip up in performance could be taken as the truth of “extremism” revealing itself.

Among first wave Han, who had, in earlier years, made friends with Uighurs, or at least socialised with them, it took a while before they all understood what was required. But Uighur, seeing friends and relatives disappear into concentration camps, understood clearly that the distinction between public and private had vanished, and they were on view, under official gaze, made legible to the party-state in even their most private spaces and moments. The only way to avoid being next to be disappeared was to perform official slogans, and only official slogans, not just when prompted, but at all times, whenever possible. Neither Kafka nor Orwell ever quite imagined this intensity of party-state rectification.

PEOPLE’S WAR AS DINNER PARTY

How does this work in practice? Here is the story of a first wave Han arriving at the house of an Uighur family known to her family, over many years:

“A middle-aged Uyghur couple greeted them effusively in heavily accented Chinese. The food was steaming on a low table that had been set on a platform. It was a meal that must have cost the family a considerable amount, given their economic status as rural farmers. Lu Yin told me, “They presented us with polu, the good kind with the leg of lamb.” She and the other three Han visitors took off their shoes and climbed up onto the raised platform.

“As they began eating, the Uyghur hosts immediately began talking about “re-education” centres. “They said in those places the guards say, ‘Who provides your daily bread?’ The answer is, ‘Xi Jinping! If you don’t answer this way then you don’t get fed!’”

“The turn in the conversation and the banality with which the couple spoke shocked Lu Yin. What was even more startling was that none of her relatives or their Han colleagues challenged what they said. They did not attempt to explain away the violence of the camp system. There was no discussion of job training or free education. Lu Yin said, “Nobody questioned this, the Uyghur family spoke about the violence of the camps in incredibly matter-of-fact ways.”

“In fact, her family members responded to this discussion of internment camps by using clichés about “social stability” and defeating the three evil forces of “separatism, extremism, and terrorism.” Lu Yin was stunned. She said, “Everyone was talking in slogans.” As she observed the scene and listened to what they were saying, she realized that the slogans were not just in the spoken words. “Inside the house, there were slogans pasted everywhere,” she said. Her relatives, the Uyghur hosts, their home, and their village had been inundated with “re-education.”

“No one interrupted the Uyghurs while they were speaking. No one contradicted what they said. When there was a gap in conversation, the refrain was ‘Uyghurs are so bad!’ The Uyghur husband and wife said in response, ‘Yes. Uyghurs are so bad.’” As they drove away from the Uyghur home, Lu Yin’s aunt began to repeat some of the things that had been discussed over dinner. “Over and over she said, ‘Uyghurs are so bad. Uyghurs are so bad. Islam is bad. The Hui are bad too.’” The others in the SUV joined in, affirming the same lines.

Lu Yin asked her aunt what relationship they had with the host family. She told her that they had been “assigned” to them. “Sometimes we bring them rice during our visits,” she said. The Uyghur couple was their “younger brother and sister.” Like over one million other mostly Han civil servants, they had been assigned to monitor and re-educate a Turkic Muslim family. Lu Yin had just witnessed this. She was also witnessing a larger transformation of Han attitudes toward Uyghurs and other Muslims who were native to Xinjiang.”

Everyone was talking in slogans. Everyone behaves as if on camera, with security state grid management monitors watching it all, for the slightest signs of deviance. No-one can trust anyone. No-one can speak their mind. To open your mouth is to betray yourself. The only safe utterance is performative declamation, as if addressing a public gathering, of officially mandated slogans.

In private, with no Han present, Uighurs feel they have to perpetuate the slogans and euphemisms: “The concentration camps are not referred to as “concentration camps”, naturally. Instead, the people there are said to be occupied with “studying” (oqushta/öginishte) or “education” (terbiyileshte), or sometimes may be said to be “at school” (mektepte). Likewise, people do not use words like “oppression” when talking about the overall situation in Xinjiang. Rather, they tend to say “weziyet yaxshi emes” (“the situation isn’t good”), or describe Xinjiang as being very “ching” (“strict”, “tight”).”

Any conscientious Han “elder brother” emplaced as eyes of the party-state captures troves of data, to be uploaded into the predictive policing system for identifying the enemy. Along with actual camera surveillance in public spaces, genomic profile of each individual, behavioural record stretching back, at least for Uighurs who had been cadres, of a voluminous dang’an personnel file, all add up. The party-state believes it has achieved panopticon omniscience, even to the extent of being able to predict future individual criminality not consciously known to the human who is thus labelled an enemy.

Fittingly, the official name of this project of enemy identification is itself a slogan, officially fanghuiju 访惠聚, an acronym that stands for “Visit the People, Benefit the People, and Get Together the Hearts of the People” 访民情、惠民生、聚民心 Fang mínqíng, huì mín shēng, jù mínxīn. Each of the three slogans, elided in common speech just as fanghuiju, has in the middle of its three characters min, people. The leadup to a people’s war starts with Han as official visitor to the people, to benefit people’s livelihood, and gather people’s hearts. The decisive classification as to whether you, and your family, are actually part of “the people” or of the enemy is cloaked in benevolent paternalistic euphemism, signalling the onset of deep inauthenticity.

Apps make it easy to make slogan chanting a public performance. “A WeChat app allows users to “fasheng liangjian” (“to clearly demonstrate one’s stance” or, literally, “to speak forth and flash one’s sword”), by plugging their name into a prepared Mandarin- or Uighur-language statement. The statement pledges their loyalty to the Communist party and its leaders, and expresses, among other things, their determination in upholding “ethnic harmony” and standing opposed to terrorism. The generated image file could then be readily posted on their social network of choice as a show of loyalty.”

[1] Michael Dutton, Policing Chinese Politics: a history, Duke, 2004, 4

[2] Austin Ramzy and Chris Buckley ‘Absolutely No Mercy’: Leaked Files Expose How China Organized Mass Detentions of Muslims, NY Times, November 16, 2019 https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/11/16/world/asia/china-xinjiang-documents.html

[3] 发动群众打赢反恐维稳人民战争, Mobilize the Masses to Win the Anti-Terrorism and Stability Maintenance People’s War, 16 November 2018. http://wap.xjdaily.com/xjrb/20181116/118967.html