ENTER HOX IL THROUGH THE EXPRESSWAY, EXIT THROUGH THE GIFT SHOP

Blog three of three updating Achen Gangyab/Hoh Xil: problematic UNESCO World Heritage

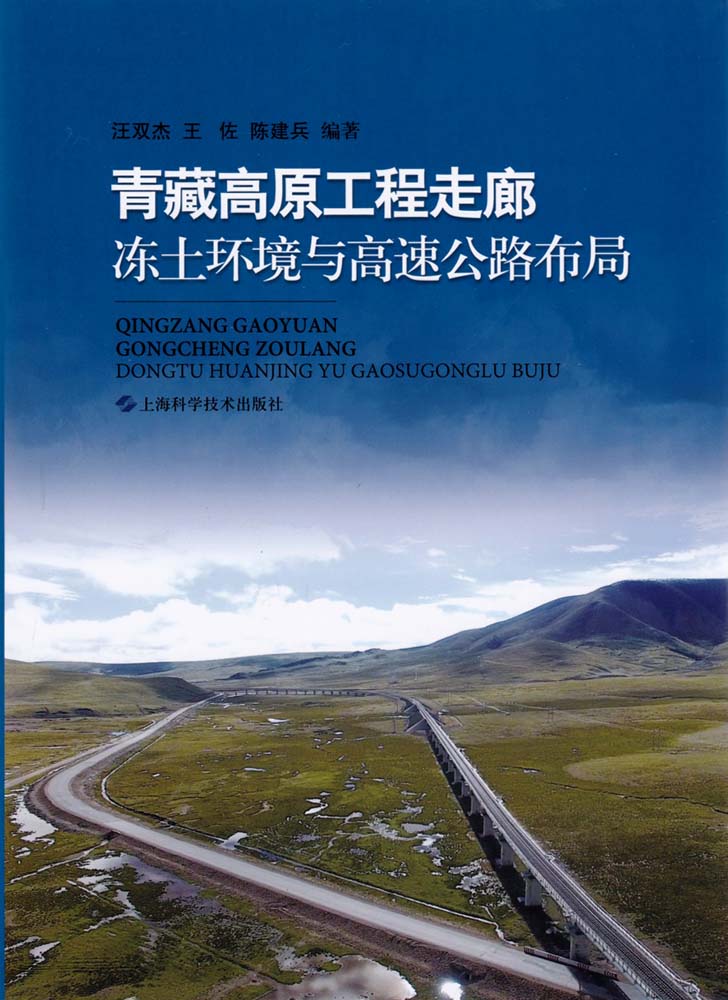

As the conservation biologists on the ground in Hoh Xil well know, the most pressing managerial decisions are to do with the new human presence, the Han presence, in the form of mass tourism, as the market responds to the prevailing romanticisation of Hoh Xil. The other looming issue, on which the field biologists in Hoh Xil want a say, is QTEC, the Qinghai-Tibet Engineering Corridor, as China has proudly named its parallel highway, railway, optical fibre cabling, power grid and oil pipeline, all of which cut across the migration path of the antelopes and gazelles. The animals head westwards, led by the pregnant females, to their birthing ground in Hoh Xil, safe from wolves, and then return eastwards with their young, a few months later. This west-east seasonal migration is bisected by QTEC, which runs north-south.

In Hoh Xil the Qinghai-Tibet Railway 青藏铁路 and Qinghai-Tibet Highway 藏公路在 are as little as 67 metres apart, as Lian Xinming reminds us, formidable barriers for the pregnant antelopes to cross, and then, months later cross again with their young at foot. Now that this highway is about to go through a major upgrade into an Expressway, Lian Xinming takes this opportunity, in his interview with Qinghai Scitech News, to plead for the reconstruction to be at least five kilometres away from the single track rail line, to give those charismatic animals a chance.

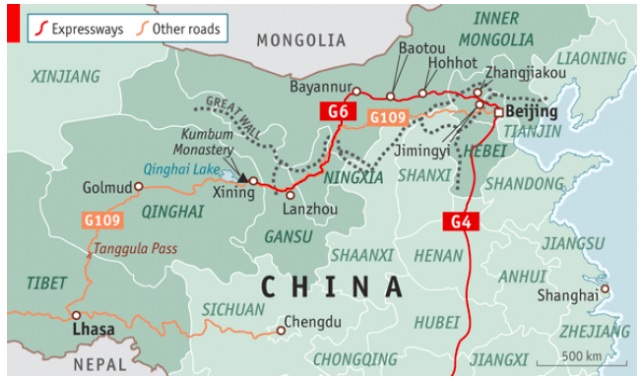

Now China is planning a massive upgrade of the highway bringing all manufactures into Tibet, from Lanzhou and Xining, en route to Lhasa. The highway is to become the G6 Expressway, the usual model being construction by a private corporation with exclusive rights to operate it as a tollway for as long as 35 years. In areas where traffic is heavy, this is highly profitable, which is why the World Bank is keen on such Public-Private Infrastructure Partnerships, as China’s path out of a state owned economy.

Who will design and who will build and operate the Tibet Expressway? How will the wild animals react to even faster traffic thundering down the expressway? This is a major project, probably centrally financed rather than contracted privately as most of China’s expressways are. Officially it is the Beijing-Tibet Expressway 青藏高速公路 . Construction began in 2014, and will soon reach Hoh Xil and beyond, all the way to Lhasa.

Officials closely engaged in its design are not reassuring. They insist the Expressway must be a completely new road, not a repair or upgrade of the existing highway, but that the old highway will still remain in use as well. So the antelopes will now have an extra road to cross.

“From a technical point of view, can the Qinghai-Tibet Highway be used to repair the Qinghai- Tibet Highway? We believe that objective conditions do not allow this because the existing Qinghai-Tibet Highway has been damaged and reuse will not save construction costs. The Qinghai-Tibet Highway will not be abandoned, and it can continue to exist as a national road, taking on necessary local passages, transportation turnover and tourism.” So said Wang Shuangjie, secretary of the Party Committee of China Communications Office and national survey and design master, in 2014.

The G6 Beijing-Tibet Expressway toll road has already reached across northern Tibet as far as Gormo, at lower altitudes. So impressive is this achievement, dashcam footage is online, at 120 kms/hr, so smooth you might mistake it for an animation, but it’s your actual Tibet sliding past.

However, China has found it difficult to build roads in Tibet, at altitudes where permafrost mysteriously comes and goes. It is hard to make an all-weather, all-season road that doesn’t slump or heave up, breaking the surface, causing traffic hazards. If you build a road in the Tibetan summer, when winter comes, and water in the soil freezes, it expands, pushing up the flat blacktop, engineers call this heaving. If road construction is done in the colder months, laying bitumen over the permafrost, the ice will melt away in spring, boosted by the heat the blacktop collects, and the road slumps. For six decades, since the first highways in the 1950s, this problem has not been solved, and a four-lane expressway is harder to construct on ephemeral permafrost than a single track rail line.

The Hoh Xil section of the Tibet Expressway is also harder to design and build than the lower altitude, permafrost-free Lhasa to Nagchu section, which is designed, ready for construction, and already has a virtual incarnation online.

Patriotic media in 2019 insist that: “Even after thousands of hardships, to build a beautiful home for 1.4 billion people and consolidate the vision of national defence construction, we must also conquer the plateau frozen soil. . With the accumulation of time, the Qinghai-Tibet Railway is difficult to support, and we cannot independently complete our mission to conquer the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. From Golmud to Lhasa, the road has a high altitude and there are 500 km of plateau permafrost regions. To lay the Qinghai-Tibet Expressway, we must overcome this world-class problem. Although we have the Qinghai-Tibet Railway’s experience in overcoming the construction of plateau frozen soil, the two projects cannot be compared. The highway is difficult to overcome the permafrost and is technically more difficult than the railway. The road is different from the railway. It is a whole structure with a wider roadbed. The materials and railways are completely different. The static load is too large. The road surface is easily affected by the frozen soil layer, causing the road to fall and rise, and there are high and low fluctuations.”

Since the trucks bringing manufactures of all kinds to Lhasa generally return empty, why is construction of the remaining sections of the Tibet Expressway scheduled for a start in 2019? Because they can. “The Qinghai-Tibet Expressway is another perfect embodiment of China’s infrastructure capacity. It is unique to the world, with such rich experience and technology. What other country on the planet is comparable in terms of infrastructure strength to China?”

Is this another example of over-investment in transport infrastructure, driven by a nation-building agenda to clasp Tibet more tightly to China, and a statist willingness to finance excessive infrastructure construction, even though the actual economic return on investment is poor? Does the actual freight tonnage leaving Lhasa, bound for inland China, justify such massive expenditure? Not at all, because Tibet Autonomous Region exports almost nothing, especially by road. So why an expensive expressway tollroad?

How does this fit with China’s love of animals in Hoh Xil?

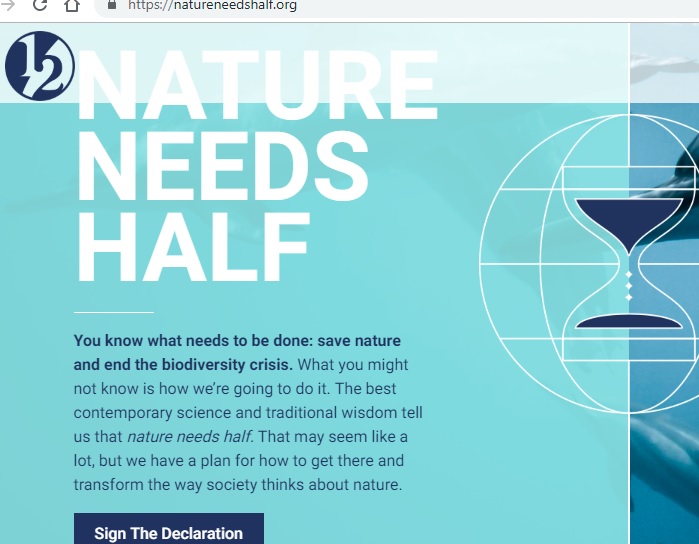

These contradictions are not unique to China. Worldwide, conservation science is messy and full of contradictions.[1] Nonetheless, wildlife conservation science and biodiversity governance are heading strongly in one direction, which may in the near future impact on Tibet. There is a growing push for as much as half the planet being officially designated as exclusively for nature.

Given the pace of urbanisation and industrialisation worldwide, in recent decades led by China, it is understandable that biodiversity conservationists are increasingly demanding more and more of the Earth be set aside as entirely natural, no longer in any way human. A recent, much-cited scientific report calls for 30 per cent of all land on earth to be “protected” from human use, a target China will achieve in Tibet. Famous biologist E.O. Wilson has called for 50 per cent of all lands to be “protected”, a call now echoed by many.

Of course no-one expects Shanghai to demolish itself and revert to wetland, nor Manhattan, nor London. Inevitably the landscapes where reversion to a pristine, pre-human landscape is even imaginable, are those areas least developed, where biodiversity remains strong, if threatened. Tibet, for example.

This is a movement growing in strength, modelling itself on the global climate change campaign, striving to advocate more vigorously on behalf of wildlife.

The problem with this approach is that it is usually dualistic, unreflectively reliant on either/or logic, with a salvific narrative of dedicated environmentalists returning an imperilled planet back to its pristine pre-human natural state, for the sake of all that lives. Nature and culture remain opposites. Human nature is inherently greedy, needy, and even sinful. The situation is urgent, there is no longer time for slow negotiations with indigenous communities to set up complex projects to dissuade them from sneakily hunting endangered species, all human presence is problematic.

The drive and urgency to save wildlife by making 50per cent of the earth out of bounds to humans usually comes from New York, London, Shanghai and other metropoles. It has been called elitist, colonialist and above all, rapt in awe at the concepts of wilderness and the pristine. The idea of winding back the clock, restoring whole landscapes to their “original” pre-human state, is seductively powerful, even if, in practice, it turns out to be an extraordinarily complex and elusive goal, just as governing the antelopes of Hoh Xil turns out to be messy and complex.

The more we all live in urban density, the more the call of the wild resonates. This vision splendid, of virgin nature, is uncannily akin to the Christian idea of the “fallen” state of human nature, stained forever by the original sin of disobeying the almighty. This is a movement likely to grow stronger, and may yet succeed in shifting the goal posts. Currently, the official goal of the UN Convention on Biodiversity (CBD) is that each country should set aside 17 per cent of its lands, lakes and rivers, as officially protected for biodiversity conservation. By making so much of the Tibetan Plateau into national parks, China is on track to meet this goal, usually called the Aichi Target, after the Japanese city where CBD met and set that goal, in 2010.

But in 2020 CBD will meet again, in Beijing, to review its biodiversity protection target for the next decade or more, amid widespread consternation that extinctions of endangered species are continuing, and the 2010 target did not achieve its aim. The push will be to hike the 17 per cent to 30 or even 50 per cent.

As with climate change, this push, even if strong, will meet strong resistance from vested interests and may well fail. But, for China, keen to claim global leadership of “green” development, it is relatively easy to assign more and more of the Tibetan Plateau as pristine wilderness devoid of humans, and, as a result, gain state control over the landscapes of Tibet that China has long sought but never achieved by its historic strategy of Han migration.

The push for closure of human use of landscapes inhabited by wildlife, as it grows louder, deafens it to its own oversimplifications, its exclusive oppositions of nature versus culture. Along with local communities in remote areas worldwide, Tibetans are caught in this growing deafness, unable to make themselves heard. Not many people want to acknowledge that there are hardly any “pristine” landscapes anywhere, or that traditional landscape managers, such as Tibetan drogpa nomads, actually curated their lands skilfully and sustainably for thousands of years, without jeopardising wild species.

The world’s governments, assembled in Beijing in 2020 at the CBD COP 15, may resist the pressure from animal-lovers worldwide to increase the target of area to be protected for biodiversity from 17to 30 per cent of the Earth. Yet, if the global climate campaign is the model the biodiversity campaign emulates, political rejection will only make the campaigners work harder to win the popular imagination, and gain momentum.

In the process, the message gets simplified; the complex negotiations with local communities to mutually protect wildlife get edited out. The message is reduced to a bumper sticker size: save wildlife or it’s mass extinction. If the wildlife is gone, we humans too are gone.

The wilderness movement and the climate movement may merge. They are both focussed on extinction as an imminent prospect, unless the world collectively mends its wicked ways. Urgency sweeps away complexity. We are all doomed if we don’t act decisively now. Anyone with memories of the 60s, 70s or 80s will recall the pervasive understanding that, in a flash, we could all be incinerated in a nuclear holocaust. That sense of pervasive dread is now returning.

Meanwhile, Beijing could emerge from the 2020 Convention on Biodiversity negotiations as the world’s exemplary protector of wildlife, thanks almost entirely to its redlining of Tibet, especially the big new national parks including the Panda National Park, Sanjiangyuan National Park and Qilian Mountains National Park.

Already on display is Hoh Xil/Achen Gangyab 阿青公加, now eternally wild, thanks to China’s success in pitching it to UNESCO. Hoh Xil is the first in a suite of protected areas across the Tibetan Plateau, a menu of opportunities for tourists to commune with nature.

This is not the only expressway tollroad into Tibet under construction. For example, there is the Shangri-la expressway punching tunnels through Gyalthang. More on that soon, on www.rukor.org

[1] Charis Thompson, When Elephants Stand for Competing Philosophies of Nature: Amboseli National Park, Kenya; 166-190 in John Law & Annemarie Mol eds, Complexities: Social Studies of Knowledge Practices, Duke University Press, 2002