Blog three of four on POVERTY, IMMISERISATION and DESTITUTION in TIBET

HOW TIBETANS EXPERIENCE POVERTY

China has for many years insisted that Tibet, usually meaning only Tibet Autonomous Region, is in fact progressing in great leaps, everyone benefits from China’s massive investment in Tibet, and incomes are rising rapidly, even if they lag far behind anywhere else in China, because Tibet by its nature lacks everything required for prosperity. Yet despite the massive capital expenditure, Tibetans remain poor. This paradox, of poverty amid huge capital inflow, has been analysed in depth by economists.[1]

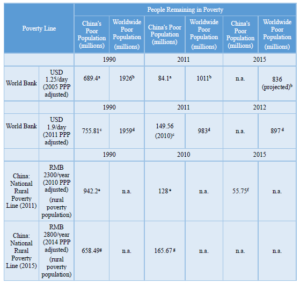

Official statistics that are publicly available, such as the provincial Statistical Yearbooks for 2017, suggest Tibetans, especially rural Tibetans, may be poor, but on average they are above the official poverty line. The TAR and Qinghai 2017 Statistical Yearbooks provide various ways of defining both incomes and consumption, based not only on calculating GDP per capita, but also on household surveys itemising how rural Tibetans spend their money. On official data, in 2016, per capita consumption expenditure of rural households in Qinghai was RMB 5619 and in TAR 5952, equivalent to USD 945, above the World Bank poverty line of USD693 per person per year.

Wealth is now accumulating in Tibet, after 40 years of rapid wealth accumulation across China. Readers of Tsering Wangmo Dhompa’s vivid Coming Home to Tibet see through Tibetan eyes the seductive pull of the shiny new motorbike or the warmth of a heated shopping mall, even in the remotest rangeland. https://www.shambhala.com/videos/tsering-wangmo-dhompa-on-coming-home-to-tibet/

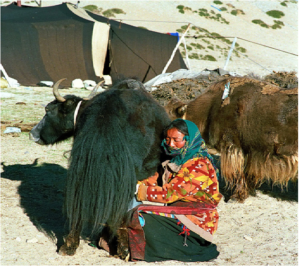

There is poverty in Tibet. This is not new. In a vast land where pastoral livelihoods are made from an unpredictable climate, where it can snow heavily and suddenly even in summer, Tibetans are expert at not only living despite uncertainty, but from it.[2] Out on the open rangelands, pastoralists know from daily experience that anything can happen, and do not have the modern compulsion to control every risk.

Life is risky, today’s rich man can quickly become poor, and vice versa. When that eventuates, the lamas remind Tibetans not to dwell on changes in fortune, or demand to know: why me? Sudden shifts are not a sign of divine providence, virtuous morals or divine punishment, but are to be attributed to accumulated past karma of previous lives, unknowable and not worth speculating about.

Adversity can reduce a prospering pastoralist to destitution as quickly as an unexpected snowstorm can block a pass, and animals die, not only of cold but lack of feed as they were about to be led down in autumn, from high summer slopes to lower winter pastures. When a herd is devastated by a blizzard, usually relatives and friends will lend animals, if they can, to help rebuild the herd. But destitution does occur.

When disaster strikes, nomads may become beggars, lining the streets of the nearest town, seeking alms. Around the world, beggars are stigmatised, denounced as fakes and wasters, undeserving of charity; but in Tibet there is little shame in eliciting the kindness of strangers. In a land prone to earthquakes, landslides, glacial lake outbursts, blizzards and howling storms, everyone knows that beggar could well be themselves.

This is what poverty experts call transient poverty, the low point in cycling through ups and downs of the human condition. Transient poverty is not the permanent state of entire populations, caused by an environment so harsh Tibetans are forever on the brink of immiserisation. Transient poverty needs special solutions, not wholesale removals of entire populations based on categorising the entire plateau as “contiguous destitute area.”

The king upon his golden throne

Can know hunger

The beggar with his begging bag

Can know fullness

What is new to Tibet is relative poverty, the juxtaposition of enormous wealth alongside deep destitution. China defines poverty in absolute, monetised terms, but in the wider world, the relative poverty of inequality is recognised as the measure of poverty, even though this means that, as long as inequality persists, poverty persists. In Europe, poverty is defined as relative, which puts an end to the fantasy that poverty can be eliminated, like an infectious disease, once and forever.

Tibetans now see, among fellow Tibetans, millionaires who made fortunes dealing in yartsa gumbu (cordyceps sinensis) trade; or earning high salaries on the official payroll. They see nonTibetans immigrating to Tibet as sojourners routinely remitting savings and profits to relatives back home. By comparison the hard and risky work of raising animals, through bitter winters and brief summers, is relatively less and less attractive. Not so long ago the Tibetan concept of wealth –nor– was synonymous with the herd on the hoof, the sight of grazing animals on the green sward, the bounty of nature needing only to be collected for human use. Pastoralists considered themselves wealthy; not so now.

TIBETAN SOLUTIONS TO TIBETAN RISKS

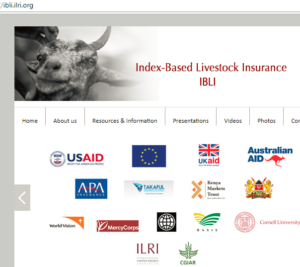

One of the simplest solutions, tailored to the risks of the rangelands, is an insurance scheme that, when a snow disaster occurs, pays nomads to rebuild their herd quickly. There is such a scheme in neighbouring Mongolia, which shares with Tibet not only a mobile pastoralist economy but also extreme weather. The Mongolians have devised a scheme that costs neither the pastoralists nor the insurance industry, yet pays promptly and reliably as needed, without time consuming and expensive wrangling over how much snow fell over exactly what area, and how many animals each nomad family lost, and did they hide some animals from the inspectors to boost the payout? Rather than parsing the specifics of each adverse event, on each pastoral property, this insurance scheme simply uses official meteorological data for a whole district, and the average herd loss, and pays accordingly. This works well, except in the most catastrophic circumstances, which can be too devastating for this deliberately modest

scheme to handle. In a real catastrophe, the state steps in with compensation.

In Ulaan Baatar, in 2013 I met with Mongolian officials in charge of this indexed livestock insurance scheme, who explained it to me in detail. I also met with international aid agencies that had been much involved in designing the scheme and in encouraging nomads to enrol in it. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1-w7iht20nw&list=PLCLZXIdq9v2RBlzJtuIR4CqRPvDVcaGBX They wanted to know why an Australian, from a country with plenty of rangeland but no traditional herders, was interested to understand their creation. When I explained that my focus was on whether such a scheme would be helpful for Tibetans, they expressed amazement. Such a scheme, they said, works only where there is trust, between the insurers and the insured. To persuade herders to enrol, and pay their annual premium, they must believe the insurers will pay, when disaster strikes. Between Han Chinese, city-based, often state-owned insurance companies and remote, disempowered herders there is no trust that contracts will be honoured. They thought I was wasting my time.

In many ways, an indexed livestock insurance scheme would serve China’s interests, as well as guaranteeing the social security of nomadic pastoralists. China’s insistence that Tibetan herders cause land degradation arises from the Tibetan preference to maintain as big as possible a herd on the hoof, rather than selling for slaughter as many animals as possible as soon as they reach adult size, which is global modern agribusiness practice. One reason Tibetans keep their wealth sentient and not on abattoir meat hooks is that, in the absence of any insurance, when snow disasters strike, a bigger herd provides a bigger base for recovery. An indexed livestock insurance scheme would incentivise Tibetans to reduce herd size, thus reducing grazing pressure, knowing they will be compensated when they most need it, when many animals have been lost.

Everyone likes a win-win, even if, in reality, they are hard to find. This is a genuine win-win, an inexpensive way of sparing livestock producers from poverty, while at the same time reducing herd size and grazing pressure. China has shown interest in this, but little has been achieved.

Much the same applies to Tibetan farmers, whose ripening barley fields in the summer monsoon season can be destroyed in minutes by a sudden hailstorm. Again, an indexed crop insurance scheme would prevent poverty.

IF DEPOPULATING TIBET IS THE ANSWER, WHAT IS THE QUESTION?

The world does not look closely at what China means by poverty alleviation. Little attention is paid to 60 years of Chinese failure to invest in the rangelands, in pastoral livelihoods, to improve herds, to enable access by pastoralists to China’s urban markets, even though affluent Chinese now eat lots of dairy products.

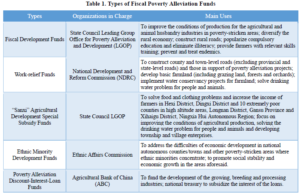

One of the few who took action to help Tibetans get out of poverty was Arthur Holcombe, who set up the Tibet Poverty Alleviation Fund (TPAF) almost two decades ago. On a modest scale, he did the work China has been reluctant to do, and in 2017 he published his reflections on what he learned.

“TPAF microcredit loans helped to enable many poor Tibetan households to invest in supplemental small household income-generating activities. For women and their husbands, this often included small investments in the establishment of village dry goods stores, tea houses, barley beer bars, and the weaving of nambu woollen cloth for sale in urban markets. For men, who would access funds from the microloans being managed by their wives, this included funding for the purchase of carpentry tools for commercial woodworking and furniture-making, and for the acquisition of small tractors with trailers to provide marketing services for fellow villagers and to work in local building and road construction projects.

“The second project involved poor nomad households in two townships and provided them with price incentives to sell their surplus yak milk to two small milk-processing plants that were located on a main highway providing easy access to an urban area. The project established rural milk-collection centres and provided vehicles that could then transport the fresh milk to the milk-processing plants that had a capacity to make high-quality yogurt, butter, and cheese prior to their sale in a main urban area. The scheme was intended to reduce the wastage of fresh milk at the household level, stimulate a demand for increased milk production and sales, and to provide nomad households with steady income for their surplus milk made possible with the steady demand for processed milk products in urban areas. “[3]

Greater wealth, greater suffering

Lesser wealth, lesser suffering

In extravagance

No virtue is accumulated

It has become a matter of national pride that “no-one is left behind” as China works towards becoming a consumer-driven middle income country. It is thus the patriotic duty of those currently “left behind” on their customary pastures, to surrender their land tenure rights, sell their yaks, sheep and goats, leave their ancestral pastures and live, on state rations, in closely monitored settlements close to Chinese towns in Tibet. These largely self-sufficient, professional land managers and livestock producers are reduced to dependence, treated, they tell us, like cattle. Yet on paper their incomes will look better in cash terms, as their self-sufficient barter economy is replaced by handouts.

In the name of

- guaranteeing provision of Tibetan glacier-melt water to lowland China,

- improving security and stability,

- poverty alleviation

- reforestation,

- carbon capture,

- grassland rehabilitation,

- biodiversity protection,

- national park management

- and rational zoning plans, these policy categories will, in coming years, work to separate the land and the people of Tibet, replacing the classic extensive and skilful land use pattern with intensive urban concentrations kept going by endless subsidies.

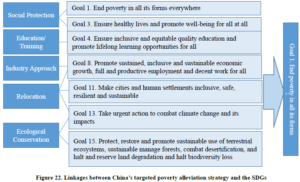

China expects to be applauded for this depopulation, as its unique contribution to human rights, wildlife protection, water conservation and poverty alleviation. The payoff for new era China is that it is acclaimed worldwide, as the greatest of civilisations, able to not only aspire to “ecological civilisation” (to use a standard Chinese official phrase), but to exemplary poverty alleviation as well, thus fulfilling human rights and thereby negating critics of China’s human rights record. The ambition is to be acknowledged as the greatest civilisation ever, a model for all others, both developed and developing, to emulate.

WHO DECIDES?

The goal of the party-state is grand, but the components constituting this utopian vision of exemplary Confucian righteousness bear closer inspection.

Poverty alleviation, like clean rivers and skies, is so self-evidently good that few look more closely at what China defines as poverty, how it measures it, what programs it has to alleviate it, how they are administered, how effective they are, who misses out, how implementation is distorted by vested interests, how the poor are stigmatised and humiliated by the poverty assessment procedures. Few examine the assumptions built in to definitions of poor areas, and the reasons poverty is geographically concentrated.

China now has that mandatory quota of 10 million poor people, each year for three years, being compulsorily moved out of poverty. China thus becomes the most exemplary of developing states, a leader among the third world, able to overcome all obstacles.

Which of the newly redefined ministries of new era China is driving the poverty alleviation agenda? None of the seven ministries with the biggest impact on Tibet focus on the welfare, social security, income support or livelihoods of Tibetans, so who will carry out the ambitious 2018 target of reducing poverty across China by a further 10 million people?

While China does have a Ministry of Civil Affairs, as well as health and education ministries, poverty alleviation is now highly centralised, and under the direct control of Xi Jinping. The agenda is in fact driven by the Central Committee for Financial and Economic Affairs, which has wide responsibilities for the whole economy, and specifically to push the poverty alleviation agenda.

What is remarkable is that not one of the top ministries has any interest in helping Tibetans stay on their land, enhance their incomes from traditional productive work, or link the traditional economy, with its distinctive comparative advantages, to the modern economy. In fact, every one of the key ministries affecting Tibet has, for differing reasons, an emphasis on removing Tibetans, depopulating the Tibetan Plateau, concentrating the Tibetan populations in towns.

WHAT DO WE MEAN BY POVERTY?

Before rushing to congratulate China for its drive to remove 10 million people from poverty in each of the years 2018, 2019 and 2020, we need to actually do due diligence. Fortunately, we have Chinese guides to help us, such as Prof Gao Qin, Director, of the China Centre for Social Policy at Columbia University whose 2018 book, Welfare, Work, and Poverty: Social Assistance in China deals with our questions, in depth.

First, in order to claim that there are only 30 million poor left in China, poverty is defined solely in monetary terms, as income of RMB 3000 per person per year, about USD500. This rural poverty definition is extremely low, missing out on including tens of millions of people a little above this cut-off. This cash income definition also accounts patchily for subsistence producers with little need for cash, because they grow and make most of what they need, as Tibetans have long done. Nor does this monetised definition of poverty attend to other dimensions of being poor, such as access to education and health, electricity, insurance or secure land tenure. It ignores the slide into poverty that accompanies ill health and disability. It is a narrow definition that ignores inequality, the relative poverty of those with little compared to those whose wealth is vast and concentrated.

Rural Tibetans make their livelihoods by taking risks. If you fall and break a bone, it’s a long way to a health clinic, where, even today, staff make most of their money selling the most expensive treatments, whether needed or not, for cash upfront. China’s poverty experts say: “Furthermore, further investigations indicated that suffering from illness is the greatest contributor to current individual or transient poverty in rural China.”[4]

Then there is the process of identifying and targeting the poor. Sometimes this is geographic, designating an entire county as a “poverty county”, with geographic factors, including climate, aridity, soil degradation, absence of infrastructure and remoteness blamed. These are the intractably poor, whose poverty is caused, officially, by their perverse choice to remain in areas of poor factor endowments. This is officially called contiguous poverty, and is thus best remedied by depopulation, and removal of people to be rehoused where there may be better economies. For China’s scientists, the concept of contiguity lends itself to territorialised geospatial cartography, generating maps purporting to show the ecologically determined inevitability of poverty in rugged landscapes such as Amdo Ngawa. Because the headwaters of the Yangtze have cut deep valleys (surface incision, handily measurable by satellite remote imagery) poverty is inevitable, China’s geographers tell us.[5]

Then there is the process of identifying and targeting the poor. Sometimes this is geographic, designating an entire county as a “poverty county”, with geographic factors, including climate, aridity, soil degradation, absence of infrastructure and remoteness blamed. These are the intractably poor, whose poverty is caused, officially, by their perverse choice to remain in areas of poor factor endowments. This is officially called contiguous poverty, and is thus best remedied by depopulation, and removal of people to be rehoused where there may be better economies. For China’s scientists, the concept of contiguity lends itself to territorialised geospatial cartography, generating maps purporting to show the ecologically determined inevitability of poverty in rugged landscapes such as Amdo Ngawa. Because the headwaters of the Yangtze have cut deep valleys (surface incision, handily measurable by satellite remote imagery) poverty is inevitable, China’s geographers tell us.[5]

In recent years, China has moved somewhat from designating entire counties as “poverty counties” eligible for county-wide central support to “precision poverty alleviation”, in which specific families are designated as poor. However, each family not only has to answer many questions in detail, their declaration of income (or lack of it) is public, affixed to their door for all to see, to their shame. Moreover, a specific official is in charge of their case, responsible for delivery of whatever they are entitled to. However, those officials, even when their promotion is formally tied to success, have incentives to keep the central funding flowing, leading to both families, and entire counties redeclared poor, year after year, to keep the fiscal flow in place, and available for diversion by rent seeking officials.

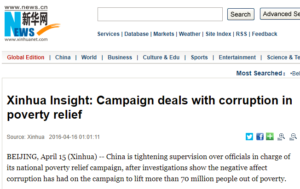

As a result of these many perverse incentives, fraud, mismanagement and corruption have been widespread, as Xi Jinping acknowledges, and those who actually are poor invariably lose out, as they are at the end of a long line of official gatekeepers who must certify poverty alleviation delivery, through whose hands funds flow.

During the day

No cattle to milk and feed

During the night

No wealth to keep the mind attached

Until the new era reorganisation of the entire machinery of government, poverty alleviation was administered by the Ministry of Civil Affairs (MCA), which has now lost many of its powers to the National Health Commission, Ministry of Veterans Affairs, the completely new Ministry of Emergency Management to manage disaster relief, State Medical Security Administration, and State Grain and Reserves Administration, which takes over organizing and carrying out the storage, rotation, and daily management of national strategic and emergency reserves which supply not cash but grain that had been held in storage for years, distributed to exherdsmen in their new concrete settlements, in lieu of a guaranteed cash income. This, as the former nomads themselves say, reduces them to cattle, dependent on handouts.

In line with the “one function, one ministry” idea, this could leave MCA more focused on poverty alleviation as its core function. However, China defines poverty as income, not consumption expenditure. Poor families are often poor because a family member is ill, or disabled, and the whole family bears the cost of treatment, which can be very expensive. In business terms, MCA is a cost centre, earning nothing, and it is now many decades since the revolutionary ideology of equality, barefoot doctors and “serving the masses”. MCA has been a weak department, and is now weaker yet. For a decade, from 1993 to 2003, a loyal Tibetan communist Dorje Tsering, 多吉才让, was Minister for Civil Affairs, the highest position any Tibetan has reached in modern China. He is an Amdowa from Labrang, and turns 80 in 2019.

The 2018 newly appointed deputy minister for Civil Affairs, Tang Chengpei, is a Han hydropower engineer by training.

DELIVERING ON THE POVERTY PROMISE

On paper, poverty alleviation has shot up in priority, is now in the hands of the Central Committee for Financial and Economic Affairs, directed by Xi Jinping. Does this mean poverty alleviation is no longer the arduous duty of an obscure ministry, and is now a high-level priority? Not so. CCFEA, 中央财经委员会, is a Party organ, a subcommittee of the Politburo. It sets policy; it does not administer or deliver policy. Several Ministers are members of CCFEA, but not the minister directly responsible for poverty alleviation, the Minister for Civil Affairs.

Official policy, in Xi Jinping’s own words, is full of commands, and threats directed at officials who distort policy delivery. At the end of March 2018 the CCP Politburo held a meeting to review poverty work and issued stark warnings against “failure in policy implementation and mismanagement of poverty relief funds, as well as misconduct such as ‘formality for formality’s sake, bureaucratism, and falsification,’ the statement said. China has adopted the strictest evaluations and assessments of poverty alleviation, which is an important guarantee in its victory in the battle against poverty and should be further improved to ensure that poverty reduction work is carried out in a pragmatic, solid and truthful way.”

This blunt language repeats warnings issued early in March 2018 by Premier Li Keqiang, on behalf of the state, who “promised targeted measures against corruption and misconduct in poverty alleviation.”

In reality, the centre can thunder but implementation remains in the hands of local government officials of many ministries, including the depleted Ministry of Civil Affairs. They persist in going through the motions of doing as instructed from far above, formality for formality’s sake, while retaining power over the poor, who must beg, as if entitlements are personal favours. In many Tibetan areas, officials, especially at county and prefectural levels, are not Tibetan, consider their job a hardship posting, and feel entitlements belong to them, whenever possible, to compensate. They have little sympathy and frequent contempt for the poor they administer. Prof Gao in her 2018 book: “the decentralized implementation of Dibao [guaranteed minimum income] allows rural officials at the county, township, and village levels considerable discretionary power, leading to several types of targeting errors such as allocating Dibao on the basis of personal connections or relationships (guanxi bao or renqing bao), cheating (pian bao), and mistakes (cuo bao). These errors also exist in urban China, but they are more widespread in rural areas given the greater challenges in checks and balances in the rural setting and more discretionary power bestowed to rural Dibao officials than to their urban peers. Rural Dibao applicants tend to be less well-informed about Dibao policies, procedures, and standards than their urban peers. They may also be less willing to complain and have fewer channels for filing grievances about injustice in Dibao implementation.”[6] Prof Gao makes these points in a 2018 podcast too.

When the poor are also landless, because, in the name of national park construction, water supply, carbon capture and wildlife conservation, landholders have been required to surrender their land tenure documents, they are even more at the mercy of nonTibetan officials. Once they have lost their lands, they are concentrated in intensive settlements, under constant surveillance, regarded officially as both indolent and indigent. Corruption among local officials who are Tibetan, and follow the example of their Han colleagues, is also not uncommon.

Despite China’s push to fully abolish all poverty by 2020, one of China’s top three “critical battles”, poverty alleviation on the ground remains messy, contradictory, and patchy in its implementation, riddled with contradictions and opportunities for corruption. Yet China is determined to succeed, and at an accelerating pace, as helmsman Xi Jinping’s standing now depends on it.

A major tool in eradicating poverty is the shift to a guaranteed minimum income for each poor household, the dibao. In the last of this series of four blogs on poverty, we look more closely at this new wave of poverty alleviation

[1] Andrew M Fischer, Disempowered Development of Tibet in China: A Study in the Economics of Marginalization, Lexington, 2013

[2] Saverio Kratli and Nikolaus Schareika, Living Off Uncertainty: The Intelligent Animal Production of Dryland Pastoralists, European Journal of Development Research (2010) 22, 605–622

[3] Arthur N. Holcombe, Can China Reduce Entrenched Poverty in Remote Ethnic Minority Regions?Lessons from Successful Poverty Alleviation in Tibetan Areas of China during 1998–2016, Ash Center, Kennedy School Harvard, 2017, https://ash.harvard.edu/files/ash/files/271837ash_tibetv4.pdf

[4] Yansui Liu, Jilai Liu, Yang Zhou, Spatio-temporal patterns of rural poverty in China and targeted poverty alleviation strategies, Journal of Rural Studies 52 (2017) 66-75

[5] Yanguo Liu, Chengmin Huang et al, Assessment of Sustainable Livelihood and Geographic Detection of Settlement Sites in Ethnically Contiguous Poverty-Stricken Areas in the Aba Prefecture, China; ISPRS International J. Geo-Information, 2018, 7, free download: http://www.mdpi.com/2220-9964/7/1/16

[6] Gao Qin, Welfare, Work, and Poverty: Social Assistance in China, Oxford U P, 2018, 51-2