Blog four of four on POVERTY, IMMISERISATION and DESTITUTION in TIBET

The more closely one looks at poverty and its remedies, the more problems arise. In 2018, as part of a major reorganisation of China’s party-state power, a new approach has been announced, in the hope of better coordination among the many ministries and agencies involved in poverty work, overcoming past fragmentation, policy failures and widespread rent seeking by powerful local officials diverting poverty funds to their own pockets.

HU’S IN CHARGE

The newly appointed Vice Premier in charge of implementing China’s poverty alleviation policies and ensuring victory in this “critical battle” is Hu Chunhua, a veteran of Tibet work.  Although he spent decades in Tibet, he has not disagreed with the official label of the entirety of the Tibetan Plateau as “contiguous destitute area.” Hu was first sent to Tibet Autonomous Region in 1983 when he was only 20, by the CCP mass organisation the party youth league. It was a time when central leaders, notably Hu Yaobang, conceded the CCP had made many mistakes in Tibet, and ordered cadres, if they intended to stay on, to learn Tibetan.

Although he spent decades in Tibet, he has not disagreed with the official label of the entirety of the Tibetan Plateau as “contiguous destitute area.” Hu was first sent to Tibet Autonomous Region in 1983 when he was only 20, by the CCP mass organisation the party youth league. It was a time when central leaders, notably Hu Yaobang, conceded the CCP had made many mistakes in Tibet, and ordered cadres, if they intended to stay on, to learn Tibetan.

By the time he was 22, Hu Chunhua was manager of the one modern hotel in Lhasa, the state-owned Lhasa Hotel, owned by the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security. This is the hotel made famous by its imported manager Alec le Sueur,  whose 1998 book The Hotel on the Roof of the World depicts a capitalist manager trying, with little success, to persuade Han danwei work unit staff to actually learn customer service, rather than treating hotel guests as nuisances.

whose 1998 book The Hotel on the Roof of the World depicts a capitalist manager trying, with little success, to persuade Han danwei work unit staff to actually learn customer service, rather than treating hotel guests as nuisances.

Hu continued to rise, too busy to learn much Tibetan. According to his China Vitae CV, by the age of 29 he led the Communist Youth League in Tibet, and in 1995, aged 32, he became deputy secretary of the party in Tibet, the second most powerful position. He reached the top, as TAR party secretary in 2001, and held it until 2007, before being transferred to senior posts in Hebei province, much closer to Beijing.

From 2009 to 2012 Hu Chunhua was party secretary of Inner Mongolia, while also climbing the central politburo ladder. Throughout his career, long after he ceased being young, the Communist Youth League was his platform, and entrée to the top. Before Xi Jinping decided he was in no need of an heir-apparent, Hu Chunhua was considered a likely contender.[1]

Before Xi Jinping decided he was in no need of an heir-apparent, Hu Chunhua was considered a likely contender.[1]

Now he is in charge of the poverty battle. By decree, it is a battle that must be won, within a predetermined, tight timeframe; yet the definition of poverty, its causes and cures remain undefined, conflicted and confused, especially in Tibet, where the party-state never invested significantly in building on Tibet’s inbuilt comparative advantage in dairy and livestock production.

Few Han cadres have spent as much time in Tibet as Hu Chunhua, who arrived in 1983 and left in 2007, with breaks for Party School training. In those 24 years he learned to speak some Tibetan, yet in his many public performances he spoke only in party-speak, with not a hint of any ideas of his own.

Now in charge of poverty programs nation-wide, attempting to co-ordinate the many ministries and official agencies with actual budgetary responsibility for financing poverty work, Hu Chunhua has accepted the official definition of the whole of the Tibetan Plateau as a “contiguous destitute area”, divided officially into two separate destitute areas that are separated only by the political cartography of one zone encompassing all of Tibet Autonomous Region, the other “contiguous destitute area” being the Tibetan-designated counties of the other four provinces where Tibetans live.

China’s record of resettling villages, and entire districts, in the name of hydropower dam development or poverty alleviation, is at best patchy, when outcomes are investigated.[2] Promises of a better life are seldom fulfilled, hardly surprising in a country where all usable arable land is already in use. Those promises keep on being made. The poor are being displaced, for their own good, they are repeatedly told.

China acknowledges that the fragmented poverty programs of recent years, dispersed among many ministries and levels of government, have often generated results on paper that mask failure in practice. A CCP Politburo statement in March 2018 conceded that: “However, there are still prominent problems regarding poverty reduction, such as failure in policy implementation and mismanagement of poverty relief funds, as well as misconduct such as ‘formality for formality’s sake, bureaucratism, and falsification,’ the statement said. China has adopted the strictest evaluations and assessments of poverty alleviation, which is an important guarantee in its victory in the battle against poverty and should be further improved to ensure that poverty reduction work is carried out in a pragmatic, solid and truthful way, it said.”

DOES DIBAO POVERY ALLEVIATION WORK?

Officially, every Chinese citizen is entitled to a guaranteed minimal income, known as dibao.

Prof Gao, in her exhaustive survey of available information on poverty alleviation, finds again and again that there has been little independent verification that official policies work as intended, and what little information that is available is focused on urban areas, rather than the remote rangelands where Tibetans have always lived. However, she finds evidence that in rural areas four per cent of the population are eligible for dibao assistance, of whom three-quarters actually receive it.

In her 2018 book on dibao, Prof Qian Gao finds that: “Dibao’s anti-poverty effectiveness is limited and at best modest, largely due to its targeting errors and gaps in benefit delivery. Because relative poverty lines are often set relative to the median income in society and tend to be much higher than the more widely used absolute poverty lines, Dibao’s effects on reducing relative poverty are particularly limited. Dibao has had minimal effect on narrowing the income inequality gap in society. Dibao’s effectiveness in reducing poverty is limited by its partial coverage and delivery, thus its full potential in combating poverty has not been achieved.

“In rural areas, Dibao families had substantially lower per capita household disposable income, smaller dwellings, and fewer assets than their non-Dibao recipient peers. In a survey conducted among 1,209 Dibao recipients in six cities in 2007, when asked whether Dibao benefits were sufficient to cover their basic living expenses, only 3.7% of the respondents said yes. About half (47.9%) considered Dibao benefits barely sufficient, another one third (32.5%) said Dibao benefits were insufficient, and about one sixth (15.4%) considered Dibao benefits far from helping them meeting their basic needs.

“With regard to population targeting, across urban and rural areas, significant portions of eligible families were mistakenly excluded from receiving Dibao benefits. Others were mis-targeted or included erroneously in Dibao coverage. Rural Dibao has had more severe leakage and mis-targeting errors than urban Dibao.”

LEARNING FROM 35 YEARS OF ANTI-POVERTY WORK

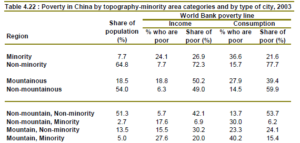

Such efforts are not new. Poverty alleviation has had programs since the mid-1980s, largely based on declaring entire counties poor, rather than specific households. Central funding was considerable, even if much of the money was for loans to the poor, who had to repay, as many Tibetans required to build permanent houses on their winter lands found. But designating entire counties as poor was not an effective way of ensuring the actual poor benefited.

Researchers from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, argued that basing poverty alleviation on designating poor counties was not working well, despite a central government spend of $20 billion on poverty work in the last 15 years of the 20th century: “We found that the amount of funds obtained by households is largely dependent on county income rather than household income. The funds are favourably distributed to households involved in non-farming activities. That is, agricultural farmers have a small chance of receiving the funds. We did not find evidence that poor households can obtain more funds than non-poor households. The findings reveal that households with more labour are more likely to get funds, suggesting that households lacking in labour force, most of them in poverty, have a disadvantage in the anti-poverty fund allocation.[3]

ACTUAL CAUSES OF POVERTY

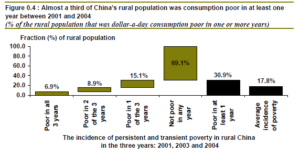

Throughout this analysis, so far, we have taken as fact China’s central planning assumption that the poor (especially in Tibet) are chronically poor, largely because they inexplicably choose to live in areas where poverty is inbuilt, due to many lacks, including ready access to markets, harsh climate etc. However, recent research by the International Food Policy Research Institute suggests that in today’s rural China, poor families are transient rather than chronic, because their incomes are unpredictable and vary a lot from year to year. In 2016 IFPRI suggested: “most poverty among our sample has shifted from being chronic in nature to being transient, with households either shifting into a state of being non-poor moving in and out of poverty. Among our sample, vulnerability to poverty has been declining over time, but the declines are not uniform over time or space. We decompose household vulnerability status into two proximate causes: low expected income and high income variability, finding vulnerability increasingly due to income variability.”[4]

China’s official approach to poverty alleviation, especially in Tibet, has been highly deterministic, attributing poverty to the soil and sky, altitude and temperature. This ecological determinism justifies removing Tibetans en masse to distant locations with different factor endowments. What if those assumptions, in contemporary China, are plain wrong?

In this era of big data, China has moved on from targeting poverty by designating entire counties as poverty counties. China now says it is doing “precision poverty targeting” that identifies (and publicly stigmatises) specific poor families. But what if their poverty is, to use economists’ jargon, “transient”?

Many studies of how Tibetans participate in the modern economy suggest that, while the older  generation seldom has sufficient Chinese to get regular paid employment in the towns and cities growing fast across Tibet, the younger generation is more literate, more mobile, and able to do demanding physical work such as road building and urban construction site labour. Those are the jobs available to Tibetans, who face competition from immigrant Han Chinese for skilled, steady work, and are generally restricted to casual, manual labour.

generation seldom has sufficient Chinese to get regular paid employment in the towns and cities growing fast across Tibet, the younger generation is more literate, more mobile, and able to do demanding physical work such as road building and urban construction site labour. Those are the jobs available to Tibetans, who face competition from immigrant Han Chinese for skilled, steady work, and are generally restricted to casual, manual labour.

This is the cause of “transient” poverty. Especially when a Tibetan family, having lost their land tenure rights, depend on the fittest young adults for cash income, the only work available is transient, casual and unregulated, with no worker rights. A lot of this unpredictable casual construction work happens mostly in the warmer months, when Tibetan farmers and pastoralists are at their busiest, taking the able bodied young away from home exactly when they are most needed.

Construction work is not only unpredictable but dangerous, and accidents happen. Medical treatment is costly, and hospitals usually demand payment upfront before a patient is admitted.

These are all reasons a Tibetan family can go from being well above the poverty line, to well below, quite quickly. On the other hand, if they have managed to keep some of their animals, to be tended by relatives who are yet to be relocated and still have access to land, and the weather is not extreme, they may be able to move quite quickly out of poverty, for a while. However, those without their land now live in a cash economy, and have to pay for everything they used to produce for themselves. If state payments they are entitled to are actually delivered, they have to last a long time, in families unused to budgeting. These are among the reasons for transient poverty.

INCOME, REMITTANCES, BOOMERANGS

China’s “precision targeting” is not precise enough to provide a safety net for Tibetans experiencing seasons of poverty, as poverty is defined only as income, not expenditure. These days, in the name of national park construction, nomads are instructed to demolish fencing they were required to erect only 10 or 15 years ago. Often, the expense of compulsory fencing, and compulsory construction of a winter dwelling, though subsidised by poverty funding, required them to take a loan, to be repaid over many years. At a time when nomads are removing fences, to let migrating wild herds range freely, many such loans are still due.

This sketch of contemporary Tibetan poverty fits with the IFPRI analysis of rural China generally: “vulnerable households have lower observed incomes, lower expected incomes, and greater income variability. These are almost definitively indicative of vulnerability, given our methodology for estimating vulnerability. But vulnerable households do not only have generally lower incomes, they are also less diversified. Vulnerable households derive, on average, nearly 65% of their income from agriculture, whereas non-vulnerable households derive only about 45 of their income from agriculture. Non-vulnerable households derive a significantly greater share of their income from formal wage employment and unearned sources (including remittances) than do vulnerable households (30% and 15%, respectively, for non-vulnerable households as compared with 15% and 10%, respectively, for vulnerable households). Vulnerable households are younger, with more than twice as many dependents and 20% fewer working age household members. Vulnerable household heads have less education, as do vulnerable household members in general. Vulnerable households have significantly lower levels of asset ownership, including the important income-generating agricultural assets and commercial capital, but also the other forms of assets such as housing capital, transportation capital, and durable goods.”[5]

While remittances sent home to the family by workers migrating to distant provinces lift families out of poverty, this is very seldom available to Tibetans. This is because Tibetans are largely immobilised by security state restrictions on movement outside of their designated hukou household registration area, and because few Han Chinese are willing to provide steady employment to Tibetans. In fact, Tibet itself has become a remittance economy for immigrant sojourning Han, who make quick money in Tibet under flexible rules enabling them to transfer hukou from their home province to Tibet and back again when they leave.[6]

LEVELLING A TILTED PLAYING FIELD?

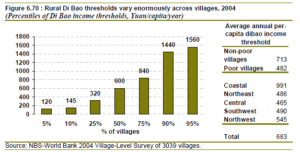

New era China is rapidly centralising authority in very few hands. Poverty alleviation has risen in priority, as a core task of making China exemplary, and in order to accomplish the frequently reiterated goal of fully eliminating all poverty in China by 2020, responsibility for accomplishing that goal has also been centralised, with the CCP’s Central Committee for Financial and Economic Affairs in command. Yet the reality is that poverty alleviation has been highly decentralised, not only in who does the work of implementation, but also where much of the funding comes from, and even in the basic definitions of what counts as poverty. A 2017 review of rural dibao minimum income programs, by economists from the World Bank, British and Canadian universities reminds us that: “Although a national program, implementation remains decentralized: eligibility thresholds, beneficiary selection, and transfer payment amounts are determined locally. The program’s decentralized nature and considerable variation in thresholds and transfer amounts raise questions regarding the advantages and disadvantages of decentralization of public transfer programs.” [7]

They suggest centralisation could ensure more effective and consistent delivery of poverty alleviation, but only if at the same time there is an overhaul of targeting. In reality, for decades, poverty alleviation targeting has classified a wide range of rural population groups as eligible targets. While it might seem obvious that ethnic minorities are targeted, and communities/counties in remote and mountainous areas, also on the list are “revolutionary bases”, where the PLA, fleeing the armies of China’s government in the 1930s sought refuge, and time to begin again the revolutionary conflict. This jumble of categories has yet to be resolved.

data for all urban residents of TAR 2016

POOR COUNTIES PAY THE POOR POORLY

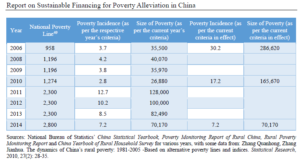

A major constraint has been the insistence of central leaders that local governments, even in poor counties where local government has little revenue, must contribute to the cost of dibao payments. This makes dibao payments highly variable. In 2007 dibao recipients on average received RMB 466 per person (US$60); by 2009, this rose to RMB 816 per person (US$119). This is hardly a generous level of support for the poorest of the poor.

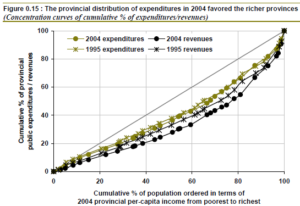

The same has been true of spending on health and education, which have also been downshifted to local county responsibilities. As with income support, there are central programs to assist the poorest counties, but if a county is so poor it cannot meet the central party-state requirement of providing a matching sum equal to the central funding, it will continue to miss out, and the poor, the ill and illiterate yet again are the losers.

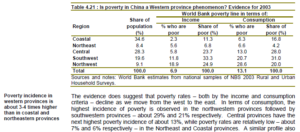

The jumble of eligibility criteria, ineffective targeting, inability of poor counties to support their poorest residents, and the low level of actual income support add up to a failure, despite official policy, to achieve much actual reduction in poverty. Yet officially China is now down to the last 30 million of intractably poor, and they too will soon be no longer poor.  The picture, at a national level, is glowing: a central state both able and willing to do what very few developing countries ever achieve: the full elimination of poverty. Seen locally, however, the picture is very different:

The picture, at a national level, is glowing: a central state both able and willing to do what very few developing countries ever achieve: the full elimination of poverty. Seen locally, however, the picture is very different:

“In early 2007 the central government announced that the rural dibao program was to be implemented nationwide in all counties and with central subsidies. Under this new national initiative, the program would become more standardized and would absorb or complement several pre-existing programs that had provided subsidies for poor households, such as the five guarantee (wubao) program and the subsidy program for destitute households (tekun jiuzhu). Although central funding of the program increased, the program was to be co-funded by local governments based on their fiscal capacity, and the minimum income thresholds and subsidy amounts continued to be set locally at the county level in light of local fiscal capacity. Official statistics indicate that the rural dibao program grew quickly after 2006. In 2007, the first year of nationwide implementation, the rural dibao program provided transfers to 36 million rural individuals (4.9% of the rural population) and accounted for three-quarters of the rural recipients of social relief. By 2011 program participation had levelled off at about 50 million individuals, equivalent to 8% of the rural population.

This is more than double the size of the urban dibao program (23 million) and outnumbers by a large margin the sum total of participants in all of China’s other rural poverty relief programs (17.9 million in 2010; does not include disaster relief).

“Spending on the program also grew. According to the official statistics, in 2007 government spending on the rural dibao program was 11 billion yuan, with an average transfer amount of 466 yuan per recipient. In 2009 spending on the program was 36 billion yuan, with an average transfer of 816 yuan per recipient. The number of recipients levelled off after 2010–11, but program spending continued to expand, implying further increases in transfers per recipient.

As of 2015, total spending reached 93 billion yuan, averaging 1,900 yuan per recipient.

Due to the diversity of China’s rural economy and the difficulty of measuring income for rural households, the dibao program’s implementation has differed among localities and evolved over time. Local variation and flexibility were explicitly built into the central government’s dibao policy regulations.”[8]

On official figures, rural dibao recipients by 2015 received on average RMB 1900 per person (US$ 292), enough to make a difference between destitution and achieving basic security. But, far from greatly reducing the number of rural poor, ineffective targeting means the number of poor in China, despite considerable expenditure, remains much higher than the official figure.

Selection of beneficiaries remains very much in the hands of the most local of officials, who inevitably favour those they are on best terms with. “Variation exists in the extent to which applications are open versus by invitation of local officials. In practice, village leaders often identify potential beneficiaries and invite them to apply. Village committees, which include village leaders and other community members, play a central role in identifying and screening potential beneficiaries. Members of village committees live in close proximity to and have local knowledge of

potential beneficiary households. Applications or nominations for dibao benefits are submitted to the township government and forwarded to the county Department of Civil Affairs. Decisions are made by township and county officials, who review the documentary evidence submitted by households and villages, and who sometimes visit the households to check on, or to collect additional, information.”

Our focus has been on the minimum income program, the dibao. However such income support (transfer payments in the jargon of economists, recorded as such in China’s Statistical Yearbooks) are just one of many methods of assisting the poor. There are many poverty alleviation strategies, used worldwide, to empower the poor to better access wider markets and other strategies for strengthening livelihoods, without any need of relocation.

Xi Jinping does know about these many strategies, for which, despite restructuring the government, many official agencies must be involved: “We should mobilize the energies of our whole Party, our whole country, and our whole society, and continue to implement targeted poverty reduction and alleviation measures. We will operate on the basis of a working mechanism whereby the central government makes overall plans, provincial-level governments take overall responsibility, and city and county governments ensure implementation; and we will strengthen the system for making heads of Party committees and governments at each level assume the overall responsibility for poverty alleviation. We will continue to advance poverty reduction drawing on the joint efforts of government, society, and the market.”[9]

This complexity means everyone is responsible for poverty work, in a system where everyone sharing responsibility often means no-one feels responsible. Responsibility remains diffused, and the menu of poverty alleviation strategies is often contradictory. Some options emphasize self-help, local solutions, strengthening existing economies; others insist on relocation and depopulation. The concept of “contiguous destitute areas” can be used to build up local economies, and to justify mass displacement. Xi Jinping on method: “We will pay particular attention to helping people increase confidence in their own ability to lift themselves out of poverty and see that they can access the education they need to do so.”

Xi Jinping exhorts all of China’s citizens to “re-liberate thought” (解放思想) and do the work of “self revolution and self reform” (自我革命、自我革新). However, his own thinking is stuck in historic prejudice, in the viewpoint of the peasant farmer on a tiny plot of arable land looking with disdain at the nomad, who has such huge areas available and see mingly does so little with them. The nomad seems so wasteful, unproductive and even destructive of the grassland wilderness. Ancient concepts of Confucian rectitude, such as self-reform, now form the basis for a rejuvenation of all that is old in today’s new era China.

mingly does so little with them. The nomad seems so wasteful, unproductive and even destructive of the grassland wilderness. Ancient concepts of Confucian rectitude, such as self-reform, now form the basis for a rejuvenation of all that is old in today’s new era China.

The thinking of the central leaders reproduces China’s inbuilt historic animus towards the dangerous, unpredictable nomads[10], but with several added layers of scientistic concepts, of carrying capacity, biomass growth, ecological environment, pristine national park wilderness, contiguous destitute areas, precision poverty alleviation, all of which require Tibetans to leave their pastures and farms, perhaps to leave Tibet altogether and assimilate into Han Chinese lowland cities. The Tibetans will inevitably merge into the great Zhonghua minzu, the Chinese race, and they will be all the better for it. That is China’s hope.

Tibetans will, of course, resist this trajectory planned for them, and continue doing so without extreme resistance that triggers the total crackdowns we now witness in Xinjiang. Tibetans have learned over the decades where China’s red lines are, not only the overt ones, like the territorialised “contiguous destitute areas” but the covert, implicit fears and racist assumptions of today’s China. Tibetans know how to assert Tibetan points of view, right up to those red lines, without transgressing them. Some kind of middle way seems to be still possible.

What such a middle way might look like, in Tibet, on poverty, is clear when we look at the recommendations from the Tibet Poverty Alleviation Fund, in its 2017 reflection on its two decades of work in Tibet:

“1. Government poverty reduction efforts should stress “bottom-up” best practices targeting and incorporating poor individuals and households in a more integrated approach than generally followed by local government to provide for income and food security needs; 27

- The more integrated approach should target improved livelihood needs as well as related environmental protection and cultural preservation requirements;

- Best practices identified as important in reducing poverty should be adapted to local wishes, needs, and priorities through a local consultative process, and not imposed when not agreed to by the poor households;

- Local government should plan its household and individual poverty reduction activities in a more holistic manner, taking into account a more comprehensive activity cycle: initial planning, implementation, monitoring of results, evaluation of results, and reporting back to leaders (as required by Xi Jinping);

- In minority areas, ethnic minority personnel with knowledge of the local culture, attitudes, and language should play the key role in planning and implementation. This is critical to getting needed local acceptance and support during implementation;

Recommendations: 1. Review the ranks of Tibetans in government civil service to determine which ones might be given greater responsibility in the planning and implementation of poor village and household poverty reduction activities;

- Establish a roster of Tibetans out of government and their skills for possible recruitment for poverty reduction work;

- Give a greater role for local NGOs, especially ones with skilled Tibetans, to be subcontracted for village poverty reduction activities;

- Aim at incorporating improved behaviour practices into poor household poverty reduction activities that are compatible, sustainable, and reinforcing within the Tibetan culture;

- Establish a framework for Tibetan monks, nuns, and monasteries to provide essential developmental, secular, and spiritual support services to poorest households and communities.”[11]

Poverty alleviation is not as straightforward as it first seems, despite Xi Jinping’s insistence that by 2020 ALL rural poverty anywhere in China will be gone forever.

Another issue not as straightforward is environmental protection. When China announces a system of national parks across Tibet, everyone applauds. National parks are so obviously a good idea. Few have the time, (in a world of distractions) to ask what exactly does China mean by national park, how does a national park include its traditional residents, as ongoing stewards of land, biodiversity and sustainability. However, it turns out China’s concept of national park is not what you may expect. More on this in future blogs.

[1] South China Morning Post (Hong Kong), October 21, 2017

[2] Brendan A. Galipeau & Mark Ingman & Bryan Tilt, Dam-Induced Displacement and Agricultural Livelihoods in China’s Mekong Basin, Human Ecology, 2013, 41:437–446

[3] Xinming Yue and Shi Li, Targeting Accuracy of Poverty-Reducing Programs in Rural China, China & World Economy, 101-116, Vol. 12, No. 2, 2004

[4] Patrick S. Ward, International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), Washington, DC, Transient Poverty, Poverty Dynamics, and Vulnerability to Poverty: An Empirical Analysis Using a Balanced Panel from Rural China, World Development Vol. 78, pp. 541–553, 2016

[5] Ward, Transient Poverty, 2016, 551-2

[6] Andrew Martin Fischer, The Political Economy of Boomerang Aid in China’s Tibet, China Perspectives, #3, 2009

[7] Jennifer Golan, Terry Sicular and Nithin Umapathi, Unconditional Cash Transfers in China: Who Benefits from the Rural Minimum Living Standard Guarantee (Dibao) Program? World Development Vol. 93, pp. 316–336, 2017

[8] Unconditional Cash Transfers in China: Who Benefits?, 2017, 318

[9] Xi Jinping, Secure a Decisive Victory in Building a Moderately Prosperous Society in All Respects and Strive for the Great Success of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era, 42-3

[10] Nicola di Cosmo, Ancient China and Its Enemies: The Rise of Nomadic Powers in East Asian History, 2002

[11] Arthur N. Holcombe, Can China Reduce Entrenched Poverty in Remote Ethnic Minority Regions?Lessons from Successful Poverty Alleviation in Tibetan Areas of China during 1998–2016, Ash Center, Kennedy School Harvard, 2017