UNESCO WORLD HERITAGE THREE PARALLEL RIVERS PROTECTED AREA UNDER THREAT

Blog three of three

MINING PERSISTS INSIDE WORLD HERITAGE PROTECTED AREA

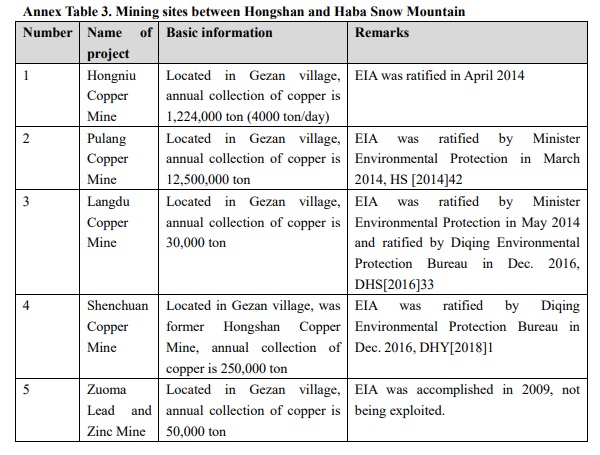

Other industries, within UNESCO’s World Heritage protected area, have drawn expressions of concern from UNESCO, notably mining. Yunnan is known for its copper deposits, for which demand grows as the power grids sending hydropower far to coastal eastern China grow. For centuries, copper was extracted from many locations in Yunnan from open pits, damaging wide areas. Today, China is part of a global mining industry, owning modern copper mines in Africa and Latin America, largely underground. However, in spite of repeated UNESCO protests and Greenpeace exposés, open cut surface scratching mining of copper, also molybdenum, still persists.

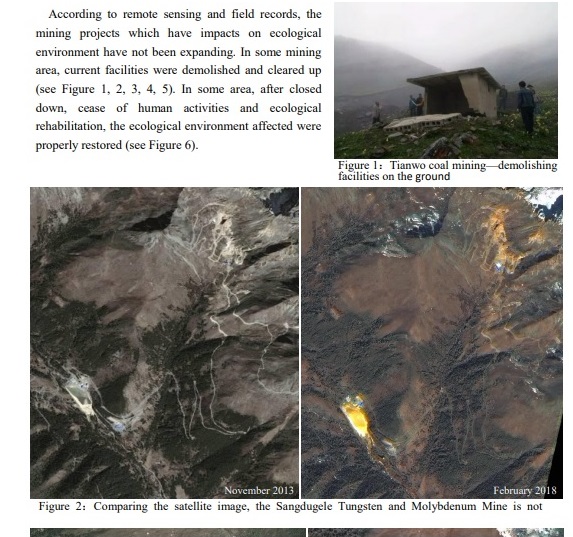

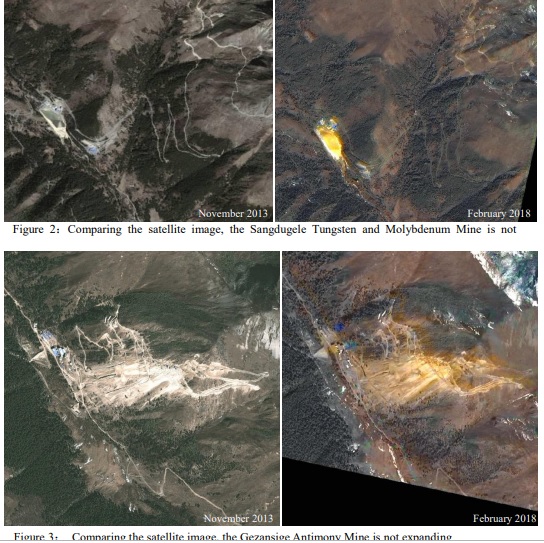

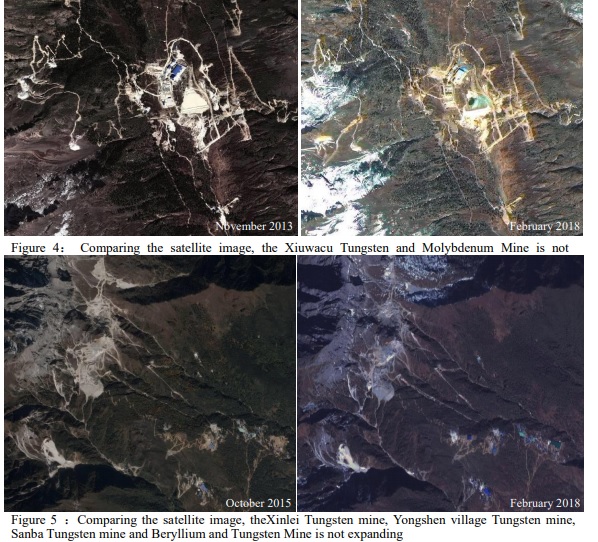

In response to UNESCO’s diplomatic concerns, China’s Nov 2018 State of Conservation report lists many small mines which, on paper, are no longer licensed. 2018 State of Conservation report by the State Party: http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1083/documents

China has given such assurances before, only to be proven wrong by evidence on the ground. Now in its latest report China provides evidence, not on the ground but in photos taken from hundreds of kilometres away, that in recent years mining at specified sites has not grown. Reliance on satellite camera pictures, supplied by the Chinese government agency in charge on the ground, the State Forests and Grasslands Administration, is not a convincing proof of effective control of a World Heritage. More convincing would be fieldwork proof, on the ground, from the folks in charge.

ADMIRING THE CONQUEST OF NATURE

Altogether, ongoing copper and molybdenum mining, water diversion and the Tiger Leaping Gorge dam at the head of 17 to 25 dams further down the Dri Chu/Jinsha add up to major impacts on World Heritage. The Longpan dam will require emigrating 100,000 people to be relocated elsewhere.

But there are further impacts: two high suspension bridges spanning Tiger Leaping Gorge, one for an expressway road, another for high speed rail. 丽香铁路

A full 27 mins animated doco on the engineering wonders of punching an expressway into Tibet at Tiger Leaping Gorge This expressway is a tollroad, built by a private company which has a guaranteed 35 years of exclusive operation to make its profits, according to the World Bank.

The rail bridge next to the expressway is taking shape more slowly, but also has its enthusiasts for the short version and stirring music, or a more lyrical 15 min version of the conquest of nature, or a 7min nerd’s eye view, or the official celebration of the high speed rail trip from Lijiang to Dechen (Xiang er li la/Shangrila in Chinese). This website has dozens of stories on the progress and prospects of this most beautiful of rail journeys, as it is called, and on the heroic efforts of young communists in picking up garbage left by tourists, emulating the eternal Lei Feng, heroic model worker.

GREATEST OF LEAPS

China’s developmentalist state is back in full strength, with simultaneous construction of hydropower dams, aqueducts and tunnels to divert much of the Dri Chu/Jinsha/Yangtze across 660 kms of Yunnan farmland, expressway road bridge and high speed rail bridge, all concentrated in a small area of deep gorge and raging mountain river far below the dam wall, 260 m below the expressway suspension bridge.

Taken together, the water diversion, hydro dam cascade, mandatory resettlement of 100,000 people, power grids, expressway and high speed railway, all in an area of World Heritage, add up to a comprehensive program to conquer nature and assert human mastery. Wild rivers must be tamed. Under Mao, China attempted its Great Leap Forward to prove human will can remove mountains. At that time, in the late 1950s, China was poor and had little more than mass mobilisation of human labour available. The Great Leap Forward crashed, a famine that starved 30 million to death ensued.

Today’s great leap, under Xi Jinping, is undertaken by a China that has finally fulfilled the Great Leap’s 1950s goal of catching up with the wealthiest nations, capable of permanently spanning, damming, taming and diverting the wildest of natural rivers, far outpacing that mythical tiger who only leapt the river once.

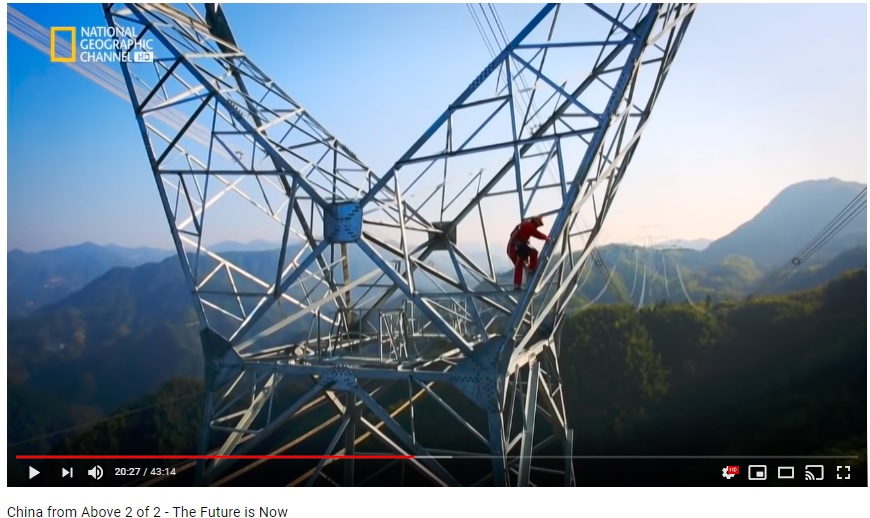

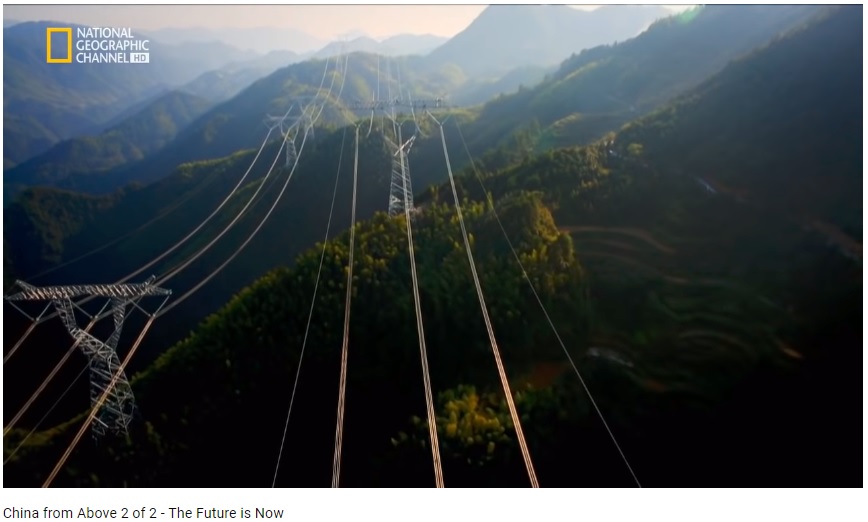

WATER CAPTURE, WATER ABANDONMENT

However, the engineering of nature turns out to be easier than the politics. All that hydropower, generated in the cascade of up to 25 dams on the Jinsha , often has nowhere to go beyond the two big hydro generating provinces of Yunnan and Sichuan, both reliant on their Tibetan Autonomous Prefectures as the dam locations. The massive investment in power grids to carry that electricity far eastwards, all the way to the world’s factory on China’s east coast, is an engineering solution, but the political problem remains. The energy importing provinces don’t want all that hydro-electricity; they preference their own provincial coal-fired power stations. This interprovincial squabble remains unresolved; and much hydro generating capacity goes to waste, despite the massive investment.

So serious is this problem of “water abandonment”, as China calls it, especially in the summer monsoon season when rivers are in full spate, that it has become one of China’s many “overcapacity” problems, along with excessive investment in steel mills, aluminium refineries etc.

Sichuan, higher up the Dri Chu/Yangtze than Yunnan, is attempting market-based incentives to, including carbon taxes, to make renewable energy hydro more attractive than coal, but official media are openly sceptical. People’s Daily says: “A hydropower industry analyst analyzed that relying on the delivery of hydropower is the most difficult to absorb: ‘For the receiving provinces, the hydropower from Sichuan province is not superior to the province’s own thermal power. It has formed a situation of overcapacity in the country’s power generation, and the thermal power unit has also been in trouble.’ The above-mentioned hydropower industry source said, ‘At the same time that coal-fired power is under tremendous pressure, inter-provincial hydropower has lost corresponding encouragement and support, eventually causing serious water abandonment in Yunnan and Sichuan provinces.’”

Damming World Heritage could be for naught. China’s hydropower industry, built and operated by huge state owned corporations, likes to present itself as part of the renewable energy, green development way of the future, along with solar and wind energy. Unlike wind and solar, hydro has huge downsides.

Nonetheless, Sichuan and Yunnan are pressing ahead with dam construction and ultra-high voltage power grid construction transmitting their energy surplus east. The 2019 official Work Report of Sichuan Provincial Government states: “In 2019, Sichuan Province will accelerate the fourth round of UHV grid routes for hydropower delivery.”

What could be more pointless than impounding rivers, only to “abandon” their waters without generating electricity? This is a classic problem of state socialism, which enables dam builders access to cheap finance, with soft budget constraints, for projects which will never be profitable if their generating capacity is not utilised, due to interprovincial protectionism. Those soft budget constraints undid the USSR.

This chronic overcapacity and underperformance are far from the rosy picture the global hydropower industry hopes to project at the 2019 World Hydropower Congress in Paris in mid-May. The big players globally are multinational corporations. The upbeat message of the Congress is modernisation, and sustainable energy solutions. China’s hydro behemoths hardly fit. There is nothing sustainable about mastering the wildest and most beautiful river in China, then letting its energy go to waste.

This is of little concern to China’s central leaders, whose ambition is to become the energy infrastructure builder and ultra-high voltage interconnector worldwide. Building more dams on the edge of Tibet, even if their waters are impounded and then abandoned, provides a showcase for China’s engineers and dam builders globally. Given such incentives, and the global ambitions of China’s GEIDCO, or Global Energy Interconnection Development Cooperation Organisation, water abandonment is a minor problem.

Similarly, UNESCO’s anxiety over China’s monetisation of its World Heritage brand is also a minor irritant at most. After all, GEIDCO is the major sponsor of the UNESCO International Water Conference. UNESCO staff, acutely aware that China is capturing an agency of the UN, are shocked but powerless. The sinews of Chinese power reach well beyond the Belt and Road, to the heart of Paris.

Is the world at last able to deal with China’s drive to conquer?

DEEPER MEANINGS OF INFRASTRUCTURE INVESTMENT

The construction of hydro dams is usually debated in a narrow way, focussing on socialist central planning, energy demand and supply, alternative technologies, the claim of hydropower to be a green equivalent to solar and wind power. These are debates worth having, especially when China is planning dozens of dams reaching further and further up the upper Yangtze, deep into Tibet.

Yet there are wider considerations. China invests so much in hydro dam construction and the infrastructure associated with dams, such as highway and railway bridges spanning the dammed rivers, for nation building reasons beyond the economics of electricity generation. Consider also the dams, the massive workforce needed to construct them, the technologies deployed in construction draw in to peripheral locations few Han Chinese could find on a map into China’s consciousness, and make the periphery Chinese.

For decades, China has been learning how to “go out” into the world, which now includes Chinese construction of dams, bridges, highways and railways worldwide. Where did China learn this expertise in “going out”, now embedded in the grand Eurasian vision of China’s Belt and Road Initiative? China’s training ground was in its peripheries, in Tibet and Xinjiang and other minority ethnicity areas.

Infrastructure investment makes these frontier lands of uncertain identification with distant Beijing into accessible, consumable portions of China as a unitary territorialised sovereign, both exotically different and thus attractive as tourist destinations, yet fully integrated in China’s nationwide network of highways, railways and power grids.

The package, of dams, expressway highways and high speed railways we see at Tiger Leaping Gorge and at other dams on the upper Yangtze, enable China to redefine itself, by looking out in order to look in. In the first decade of this century, there was an openness to a more fluid understanding of China’s borderlands, a willingness to go beyond Han chauvinist identity politics, to see China as the product of many cultures interacting.

With Xi Jinping’s new era, that openness is ended; assimilation of nonHan ethnicities is now the norm, while maintaining sufficient façade of difference to make the peripheries attractive to Han tourism, even if this involves large scale construction of ethnic “old towns”, in Lijiang and Dechen/Diqing/Xiang er li la/Shangri-la, the two towns at the ends of the Tiger Leaping Gorge expressway and high-speed railway.

So we conclude this blog series with a reflection on the deeper meanings of all that infrastructure, by Timothy Oakes, contemplating the uses of the borderland in today’s China:

“’Peripheralization’ can be viewed as a process of state territorialization in China’s Borderland regions, involving the various administrative strategies, development projects, governmental technologies, civilizational discourses, and narratives by which the periphery is reproduced as a periphery. In the single-origin myth, peripheralization has served to reproduce the frontier as a space of assimilation and transformation toward a unitary idea of Chinese culture and ethnicity, emanating from the centre outward.

“Peripheralization projects reproduce the periphery in these terms by masking and marginalizing the more complex histories of frontier exchange and mixture. China’s borderlands continue to be peripheralized as spaces of otherness by which notions of Chinese cultural, national, and territorial purity and sovereignty are reproduced. China’s borderland narratives, in other words, increasingly recognize a history of hybridity and cross-cultural connection, but nevertheless manage to enroll that history into the ‘deeply territorialized vision’ of a singular Chinese geo-body. The ongoing and fundamental role of peripheries in constituting the singular Chinese culture and identity continues, but in re-imagined and reworked ways.

“Frontiers are, in short, paradoxical spaces. They are both peripheral and central, both pure and hybrid, the source of national spirit and the distant ‘Other’ requiring transformation into the national spirit, backward spaces that also serve as conduits for technological innovation, new ideas, and invigorating cultural influences. Frontiers are sites of raw indigenes and processes of transforming those raw indigenes into cooked Chinese. Frontiers are borderlands and bordered lands.

“The frontier has

become an antidote to our technological lives filled with calculation and

traffic jams. The frontier remains central to constructions of Chineseness in

terms of purity as well. And of course, for the state, tight control over

frontier narratives remains essential. For the state, the frontier is still a

bordered land, and thus particularly important as a site of national

purification, where the ordered space of the nation must be performed and displayed

without ambiguity.” [1]

[1] Tim Oakes (2012) Looking Out to Look In: The Use of the Periphery in China’s Geopolitical Narratives, Eurasian Geography and Economics, 53:3, 315-326