UNESCO WORLD HERITAGE THREE PARALLEL RIVERS PROTECTED AREA UNDER THREAT

Blog two of three

HOW TO UNDO A WIN FOR THE ENVIRONMENT

What has changed since 2007? Why are the Longpan/Tiger Leaping Gorge dam construction plans now again high on the infrastructure construction agenda?

Much has changed, tilting the playing field in favour of the engineers. Above all, the political climate has worsened, with no-one permitted to question the central leader.

China’s environmentalists can no longer openly express their anguish. They find themselves in the same position Tibetan environmentalists have suffered for decades: silenced by diktat. This plea, written at the urgent request of Chinese environmentalists, is their only way of alerting the world that UNESCO must not, yet again, allow its precious heritage brand equity be trashed by overdevelopment in and around its World Heritage sites.

WATER EXTRACTION AND DIVERSION

What has also changed since 2007 is that central, lowland Yunnan has battled to cope with chronic excessive extraction of water, for heavy industry, intensive irrigation crop farming and fast growing cities. Lakes once admired for their beauty are now clogged with toxic algae, unusable. There were five years of rainfall deficit in central Yunnan, starting 2009, and calls grew stronger to solve all these problems by channelling off the Dri Chu/Jinsha exactly where it makes that sharp turn back towards the north.

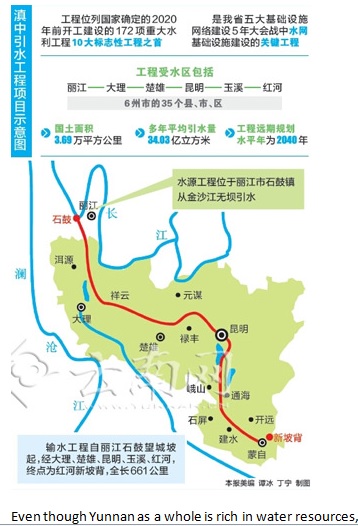

In 2016 the planned “average annual water diversion is 3.403 billion cubic meters, of which 2.231 billion cubic meters are supplied to urban life and industry, 500 million cubic meters for agricultural irrigation, and 67.2 to the Dianchi Lake, Wuhu Lake and Yilong Lake.” So says Yunnan Information News. China’s official 2018 State of Conservation report carelessly inflates the amount of water to be extracted tenfold, while insisting it is only eight per cent of the Jinsha flow at that point, despite the absence of gauging stations.[1] According to Asian Development Bank[2] the total annual flow of the Yangtze is just over 200 billion m3. China’s official report goofed.

To some, that is a modest water diversion, only 8 per cent of the Jinsha’s flow. However, among ecologists 10 per cent is the upper limit of water extraction before a riparian ecosystem is fundamentally changed. Further, it will be mostly withdrawn when the river is lowest, in the drier months from September to February. Subtropical lowland Yunnan grows crops year round, if irrigated. This is a threat UNESCO has so far said nothing about.

Water will be pumped from the Dri Chu/Jinsha at a rate of 486,000 cubic metres per hour, for 660 kms right across central Yunnan, to the capital Kunming, where it will be on display in an urban waterfall park currently reliant on a much smaller water diversion, with some water eventually reaching Dianchi Lake, making it swimmable again after decades of oxygen depleting green algae pollution. This ambitious scheme reaches as far as the upper watershed of the depleted Red River.

UNESCO has not remonstrated with China over this water extraction project, although it was publicly launched in 2015, with a construction phase of eight years. Officially it is the Dian Zhong Water Diversion Project 滇中引水工程. It is also called Suizhong. The headline for the 2015 launch: “China initiates enormous Yangtze water diversion scheme.” Publicity emphasizes theattractions of remediating smelly, toxic lakes, but most of the extra water is for industry, as specialist publications acknowledge.[3]

Yunnan has long been pushing for this low tech solution to its chronic over use of water, with first Jinsha diversion plans going back to the 1950s. Under the national “Open up the West” campaign launched by Jiang Zemin in 1999, Yunnan is rapidly industrialising and agribusiness is intensifying, in accordance with official policy, all requiring much more water. Diversion of the Jinsha to central Yunnan, and the construction of the Tiger Leaping Gorge Longpan hydro dam go together, proponents argue: “Call for the Yangtze River leading reservoir to be launched as soon as possible. Located in the mouth of the Tiger Leaping Gorge in Yunnan, Longpan Reservoir is the leading reservoir of the 17 cascade hydropower stations in the Yangtze River. It is the best water source for water diversion in the central Yunnan Province. Its comprehensive social and economic benefits are outstanding and irreplaceable. It is necessary to immigrate 100,000 people. The Suizhong water transfer plan is closely related to the Longpan hydropower station. The article studies show that the Longpan hydropower station is the best solution for water transfer in Suizhong.”[4] Pumping a lot of water uphill takes a lot of energy, so what better than to have a massive hydropower dam close by?

VIGOROUSLY MAKING THE CASE FOR DAMMING WORLD HERITAGE

What has also changed since 2007 is that the dam engineers not only never gave up on their concrete dream, they redoubled their pitch, claiming the Tiger Leaping Gorge dam would benefit everyone, even as far as the mouth of the Yangtze, close to Shanghai, over 4000 kms downriver, where it would hold encroaching seawater at bay.

The strongest pitch to get it built came in the 3rd year of Xi Jinping’s new era, in 2014, from senior hydro-engineer An Shenyi, 安申义 (Wang Sanyi) who was 88 that year. An Shenyi, the former vice president of the Central South Survey and Design Institute in Hunan Changsha and the chief engineer of the plan, leaked to reporters his calculations, and case for construction. What he revealed was widely reported in official media.

An Shenyi is a celebrated hero of pioneering dam design, and his 2014 urging that Tiger Gorge dam be built was accompanied by a glowing report in the CCP Central Committee Party School magazine, Soul of China, emphasizing his deathbed recovery from a 2010 heart attack. It became a sacred mission to fulfil this last wish of a heroic red exemplary model. An Shenyi will be immortalised in the 276 metres high dam wall at Tiger Gorge/Longpan.

With highly specific numbers, he argues that this massive dam –big even by Chinese standards- will deliver massive and multiple benefits. Not only will it hold a vast amount of water, becoming a pleasure lake, it will release water, after passing through the electricity generating turbines, well into the dry season, lifting the level of the Yangtze far downstream, sufficiently for ships as big as 10,000 tones weight to use the Yangtze reliably as a logistics transport highway far inland. That prospect of making the Yangtze navigable for ships was one of the promises of the Three Gorges Dam, which failed to materialise. Thus Tiger Gorge’s fate is inextricably bound up with fulfilling the Three Gorges promise, remediating Li Peng’s legacy, something he can be fondly remembered for rather than the unmentionable Tiananmen events of 1989.

These arguments, backed by An Shenyi’s calculations, give powerful players reasons to want Tiger Gorge dammed, from Shanghai on the coast, saved by Tiger Gorge dam from encroaching seawater, upriver to Hunan province, An Shenyi’s base, and further up all the way to Chongqing, at the farthest inland end of the Three Gorges dam. An Shenyi packages Tiger Gorge/Longpan as the start of the entire Gezhouba cascade of 17 dams serially located, and already built, further down the Dri Chu/Jinsha, below Three Gorges. This one crowning dam is to be bigger than the other 16 combined:

“The Longpan Dam is 276m high , the total head of the Gezhouba Cascade is about 1800m , and the storage capacity is 90.8 billion kWh at the time of full storage . It is equivalent to the annual power generation of the Three Gorges Reservoir, and can generate 4 kWh per cubic metre of water. In the largest energy storage reservoir in foreign countries, the storage of electricity is only 48 billion degrees, only 53% of Longpan . The storage capacity of the Longpan is equivalent to three times the energy of the downstream 16 cascades , which is very beneficial to ensure the power supply quality and power supply safety of the cascade and the combined power grid.”

This is more than a mega-project. It is a vision uniting provinces thousands of kms apart, linked by one river visualised as a single pipeline to be sluiced shut and selectively opened, a system of hydraulic civilisation construction in which, as always, Tibet is a solution to China’s problems.

Longpan is the one with the lot: flood control, drought relief, huge power output, including power pumping water uphill to central Yunnan, a green alternative to coal fired power, tourism enhanced, ship lifting: An Shenyi’s list of benefits is long, and seductively precise in its quantification.

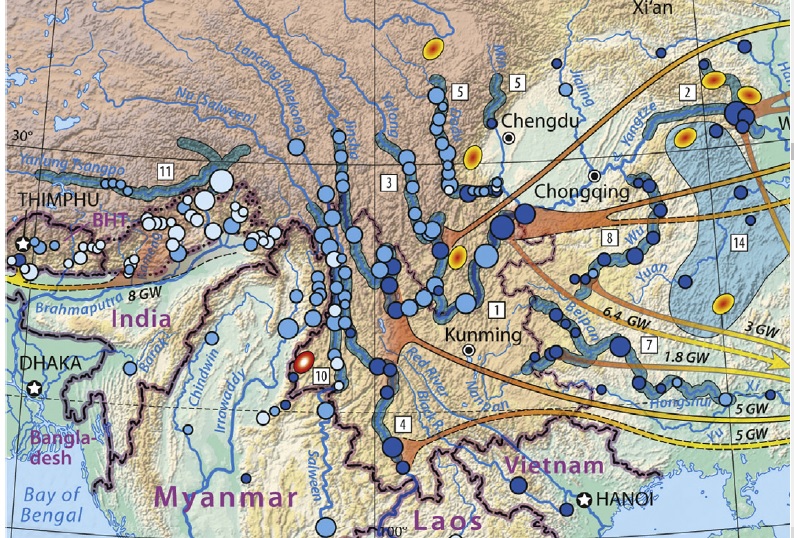

Our singular focus here is on Tiger Leaping Gorge, but it is one of many dams long planned, both up and downstream on the steep margins of the Tibetan Plateau.

As recently as January 2019 the joint directive of China’s Green Development Catalogue of Approved Projects listed the many dams scheduled for construction (if not already built), nominally within the 13th Five-Year Plan period that goes to 2020. Most of these dams have been in planning for decades, awaiting central finance. Sites further downriver, in less difficult terrain, usually got priority. China is now moving upriver, on the various branches of the upper Yangtze in Tibet (Dadu, Yalong, Jinsha) and the list is a long one. Those not built under the 13th Five-Year Plan will be rolled into the 14th Plan, for 2021 to 2026.

Here is the full list of what is officially scheduled, now branded as “green development”, from the joint announcement of the National Development and Reform Commission, Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, Ministry of Natural Resources, Ministry of Ecology and Environment, Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development, People’s Bank and National Energy Board:

Section title translation: 3.2.4 Mega Hydraulic power Generating Facility Construction and Operation.

Key mega hydropower Base Constructions which are definitely included in 13th Five-Year Plan Renewable Energy Project:

List of Hydropower station projects in Tibet

Ye Ba Tan hydropower Station叶巴滩水电站 in Palyul County (Chinese: Bai Yu), Kardze TAP, Sichuan Province. Construction of Yebatan dam began in April 2019.

Lawa Hydropower Station拉哇水电站 is at the boundary of Markham County (Chinese: Mang Kang), TAR and Bathang County (Chinese: Ba tang) Kardze TAP, Sichuan province.

Ba tang Hydropower Station巴塘水电站 is at the boundary of Markham County (Chinese: Mang Kang), TAR and Bathang County( Chinese: Ba tang) Kardze TAP, Sichuan province.

Chang bo Hydropower Station昌波水电站is at the boundary of TAR and Kardze TAP, Sichuan

Bo Luo Hydropower Station波罗水电站 is at the boundary of Jomda (Chinese: Jiang da) County, TAR and Palyul (Chinese: Bai Yu) County, Kardze TAP, Sichuan Province.

Gang tuo Hydropower station岗托水电站 is at the boundary of TAR and Sichuan Province.

All six above hydropower stations are at boundary of Tibetan Autonomous Region( TAR) and Sichuan Province. They are located along Drichu River(Chinese: Jin sha jiang/Yangtze) runs through Jomda County( Chinese: Jiang da), Gojo County( Chinese: Gong jue) and Markham County (Chinese: Mang kang) of TAR and Dege County, Palyul County (Chinese: Bai yu) and Bathang Coutny (Chinese: Ba tang) of Kardze Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture(TAP) in Sichuan Province.

Xu long Hydropower Station旭龙水电站 is located at the boundary of Derong County, Kardze TAP, Sichuan Province and Dechen County( Chinese: Di qing), Dechen( Chinese: Di qing) TAP, Yun nan Province.

Ben zi lan Hydropower Station奔子栏水电站 is at boundary of Dechen County, Dechen TAP, Yunnan Province and Markham County( Chinese: Mang kang), TAR.

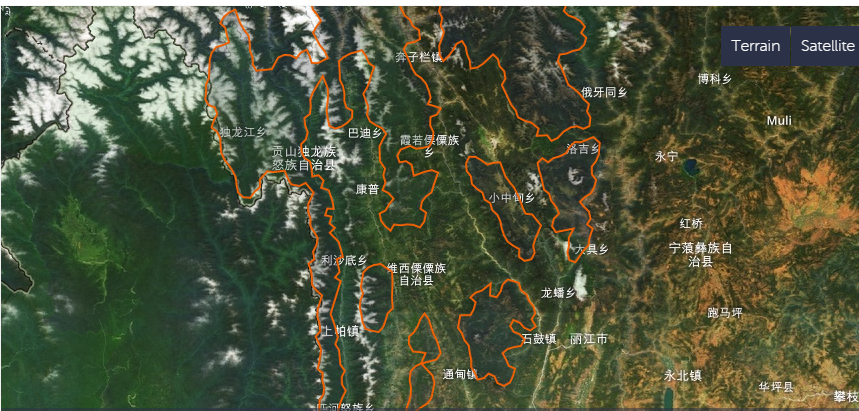

Tiger Leaping Gorge/ Long pan Hydropower station龙盘水电 is at boundary of Shang ge Li la/Shangrila (Tibetan: Sem kyi Nyida means Sun and Moon of Heart) County, Dechen(Chinese: De qing) TAP and Yu long County of Li jiang City, Yun nan Province

YALONG RIVER BASIN 雅砻江流域

Ya gen First Level Hydropower Station牙根一级水电站 is in Nyakchu County( Chinese: Ya jiang), Kardze TAP, Sichuan Province.

Meng di gou Hydropower孟底沟水电站 station is at the boundary of Gyazur (Chinese: Jiu long) County, Kardze TAP and Mu li Tibetan Autonomous County in Sichuan Province.

Ka la hydropower station卡拉水电站 is in Mu li Tibetan Autonomous County, Sichuan Province.

Ya gen Hydropower Station牙根二级水电站is in Nyakchu County( Chinese: Ya jiang), Kardze TAP, Sichuan Province.

Leng gu Hydropower Station楞古水电站 is in Nyakchu County( Chinese: Ya jiang), Kardze TAP, Sichuan Province.

DADU RIVER BASIN 大渡河流域

Jin chuan Hydropower Station金川水电站 is in Chun chen County(Chinese: Jin chuan), Ngaba(Chinese: A Ba) TAP, Sichuan Province.

Ba di Hydropower Station巴底水电站 is in Chun chen County(Chinese: Jin chuan), Ngaba(Chinese: A Ba) TAP, Sichuan Province.

Ying liang Hydropower Station硬梁水电站 is in Chagzamka County(Chinese: Lu ding), Kardze TAP, Sichuan Province.

An Ning Hydropower Station安宁水电站 is in Chun chen County(Chinese: Jin chuan), Ngaba(Chinese: A Ba) TAP, Sichuan Province.

Dan ba Hydropower Station丹巴水电站 is in Rongdrak(Chinese: Dan ba) County, Kardze TAP,Sichuan Province.

Ma er dang Hydropower Station玛尔挡水电站 is at the boundary of Ba Dzong( Chinese: Tong de) County, Tsolho(Chinese: Hai Nan) TAP and Machen(Chinese: Ma qin) County, Golok(Chinese: Guo luo) TAP, Qing hai Province.

Yang Qu Hydropower羊曲水电站 Station is at the boundary of Drakar( Chinese: Xing hai) County and Gaba Sumdo(Chinese: Gui nan) County, Qinghai Province.

Ci ha Xia Hydropower Station茨 哈峡水电站 is at the boundary of Drakar (Chinese: Xing hai) County and Ba Dzong(Chinese: Tong de) County, Qinghai Province.

Ning mu te Hydropower Station宁木特水电站 is in He Nan(Tibetan: Ma lho) County, Huang Nan(Tibetan: Malho) TAP, Qing hai Provice.

A qing Hydropower Station 阿青水电站is Tsada(Chinese: Zha da) County, Ngari(Chinese: A Li) Prefecture, TAR.

Yu Zhong Hydropower Station 忠玉水电站 is in Lhari (Chinese: Jia li) County, Nakchu Prefecture(Chinese: Na qu) TAR.

Zha La Hydropower Station扎拉水电站 is in Dzogang(Chinese: Zuo gong) County, Chamdo(Chinese:Chang du) Prefecture, TAR

On top of all that, the same central planners have also instructed Tibet Autonomous Region to invest much more in hydropower construction. Altogether, the damming of the upper Yangtze is to be on an extraordinary scale, requiring further analysis.

DISPLACING 100,000 TIBETAN AND NAXI FARMERS

An Shenyi’s clincher argument is that the 100,000 people to be displaced by the Tiger Leaping Gorge Dam will be better off elsewhere. In 2000 An Shenyi published a book on how to manage the environmental and resettlement issues, proposing the kind of win-win Xi Jinping loves to embrace.

For Tibetans and the smaller population of Bonpo Naxi (Jang to Tibetans), 100,000 people is a lot, and their farmland is precious in the rugged terrain of precipitous Kham (eastern Tibetan Plateau). Although Tiger Leaping Gorge is narrow, below it, along the 265 kms of future man-made lake the river often widens, enabling farmers to grow the glowing gold canola/rapeseed crops that feature on the splash page of the dam building corporation.

Where can those 100,000 Naxi and Tibetan shingpa farmers go? An Shenyi offers few specifics, yet he is sure their income will increase, and the economy of the future is in tourism.

This is not reassuring, as China has built thousands of hydro dams in recent decades, displacing many millions of people, and there are many research reports documenting the ongoing poverty of the relocated, despite official promises.[5]

China is chronically short of arable land, especially in rugged Yunnan. Chinese as well as international researchers find displaced villagers required to emigrate are seldom paid the actual value of their land.[6]

The displaced can do aquaculture, An Shenyi assures us, or pick

shitake mushrooms in the forest. A gourmet future awaits. Meanwhile a

global future awaits China’s dam builders and power grid builders. Blog three

in this series explains.

[1] China’s official response to UNESCO’s concerns, issued late 2018, gives much higher figure as to the extraction of Jinsha flow: “Based on monitoring information, the annual average flow at this segment of Jinsha River is 426 billion m3.The planned annual average water intake is 34.2 billion m3, account for 8% of the flow at this segment. The impact on downstream water flow is low.” State of Conservation Report, November 2018, 11. Their ratio, of 8% still holds.

[2] Asian Development Bank, Managing Water Resources for Sustainable Socioeconomic Development: A country water assessment for the People’s Republic of China, Dec 2018. https://www.adb.org/documents/country-water-assessment-peoples-republic-china

[3] Progress of the water diversion project in Yuzhong, Pump Technology, 2012, (03): 53

[4] An Shenyi, Working together to promote the Yangtze River leading reservoir as soon as possible In: Hongshui River, 红水河 2014, 33 (04): 1-2

[5] Sabrina Habich, Strategies of Soft Coercion in Chinese Dam Resettlement, Issues & Studies, 51, no. 1 (March 2015): 165-199

Shawn Steil and Duan Yuefang, Policies and practice in Three Gorges resettlement: a field account; Forced Migration Review 12, 2002 https://www.fmreview.org/development-induced-displacement/steil-yuefang

[6] Wang Xu, Promote resettlement work based on comprehensive land price and value-added income distribution, Yunnan Hydropower Journal, vol35 #5, 2018, 王旭,孔元刚,杨海青; 基于综合地价和增值收益分配推动移民安置工作, 云南水力发电