Development with Chinese characteristics

Blog two of two on China’s latest plans for upscaling poverty alleviation in rural Tibet into urbanisation, industrial agribusiness, commercialisation and accelerated lives

There are plenty of Tibetans who do embrace development and modernity with Chinese characteristics as not only inevitable but necessary. There seems to be no alternative, especially now, when China’s infrastructure investments in Tibet make the convenience and comfort of urban life more accessible than ever. It is not just the standard economistic propositions of neoliberal efficiency and scale that resulted in health care and education being concentrated in towns and cities. In the past decade as much as 80 per cent of village schools in Tibet were closed, in favour of bigger, centralised schools in county towns, where children must board and can only see their families in holiday time. The business case may emphasise efficiency, but the party-state agenda goes deeper. Fragmentation of families, weakening customary bonds and loyalties are a first step in creating individuals who display their individuality through their consumption, who identify above all as Chinese, leaving behind their customary ethnicity. The full package requires big changes to the self.

Tibetans in Tibet, seeing no alternative, often embrace modernisation, in the hope that it can live up to its promise of making life more convenient and comfortable; without dislocating values Tibetans have always seen as important, such as consideration for all sentient beings, long term preparation for consequences of present actions, patience, forbearance, spaciousness, flexibility.

At first the move from an old house to a new one, although expensive and requiring debt, may seem modest, especially if the newly constructed housing is not far from the old. But dislocation is a conveyor belt, an assembly line of new identities, ever accelerating. Once the conveyor belt has begun conveying, there is no stopping, no going back. Individuals are in competition for secure work, and competition intensifies as one ascends. In a networked society, where one must have the right connections, Tibetans and Uighurs enter the workforce disadvantaged from the start, because their spoken and written Chinese may not be good enough, because they lack certified training, lack a certified work history, and especially because they lack a network of connections among Han.

SEARCHING FOR TIBETAN BILLIONAIRES

The new era that dislocated Tibetans now enter tells them they can succeed if they work hard enough. But they are outsiders, of an ethnicity mistrusted and even despised. In contemporary modernity productivity is all, but productivity is selectively and narrowly defined, as delivery of services in specified times and places, at specified prices, according to contracts not written by entrants but by the already privileged.

China’s richest man makes his money by selling bottled water. Tibet Water has been a highly successful Chinese corporation domiciled in Hong Kong. Where are the Tibetan billionaires making fortunes from bottling pure Tibetan water? Marketable Tibetan purity of water source is highly profitable, in a country where contamination is a widespread fear, and there is a middle class of hundreds of millions of people willing to pay for guaranteed purity. Is making billions the definition of success, of having finally acquired suzhi? Or is there reason to suppose the party-state would see a Tibetan billionaire as dangerous competition, and bring him/her down?

Such speculation can only be speculative, yet having some idea of the destination does matter at the start of a journey. What if the purported destination ever recedes over the horizon? There is an inexorable logic to the urgings of economists to embrace scale as the engine of efficiency, requiring everything to forever get bigger and faster. Consolidated pastures must consolidate further and get ever bigger, or be left behind by competing enterprises that have upscaled and can produce animal protein more profitably. Consolidated farmland must consolidate further, invest more in technologies that standardise production, in the name of efficiency. Processors of rural production must merge, through corporate takeovers, to become globally competitive and maximise profits, even if that means treating local pastoralists and farmers badly.

DELUSIONS OF SPECTACULAR MODERNITY

Do Tibetans understand the danger that modernity is an escalator without end? Almost certainly, they do. Many Tibetan teachers warn of the dangers of irretrievable enmeshing with the globalised productivist ideology, even if they can’t overtly call it that. Plenty of Tibetan teachers have seen the wider world, move easily through city life, mingle with rich and super-rich followers in China and elsewhere, and are highly aware of how addictive the accelerations of modernity are. They teach all who will hear that the race for accumulation is delusional, unsatisfying, at best ephemeral.

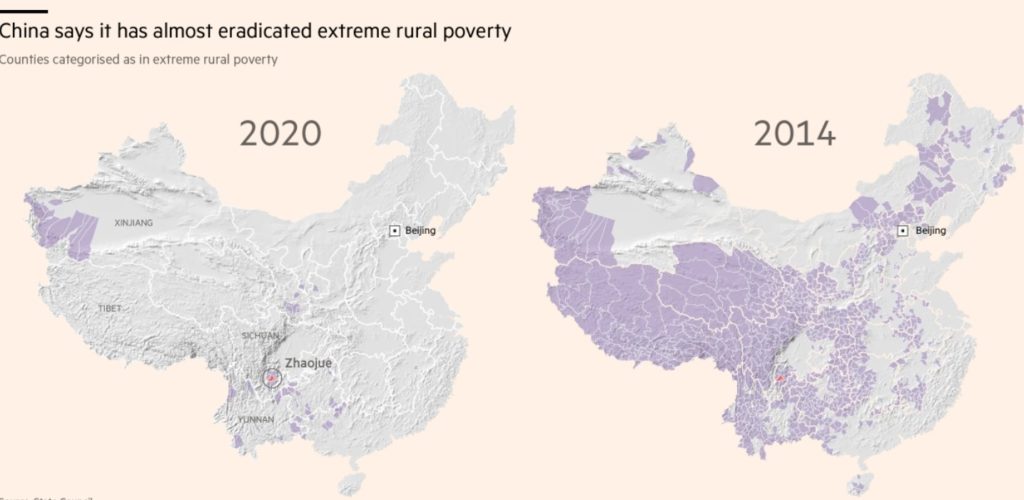

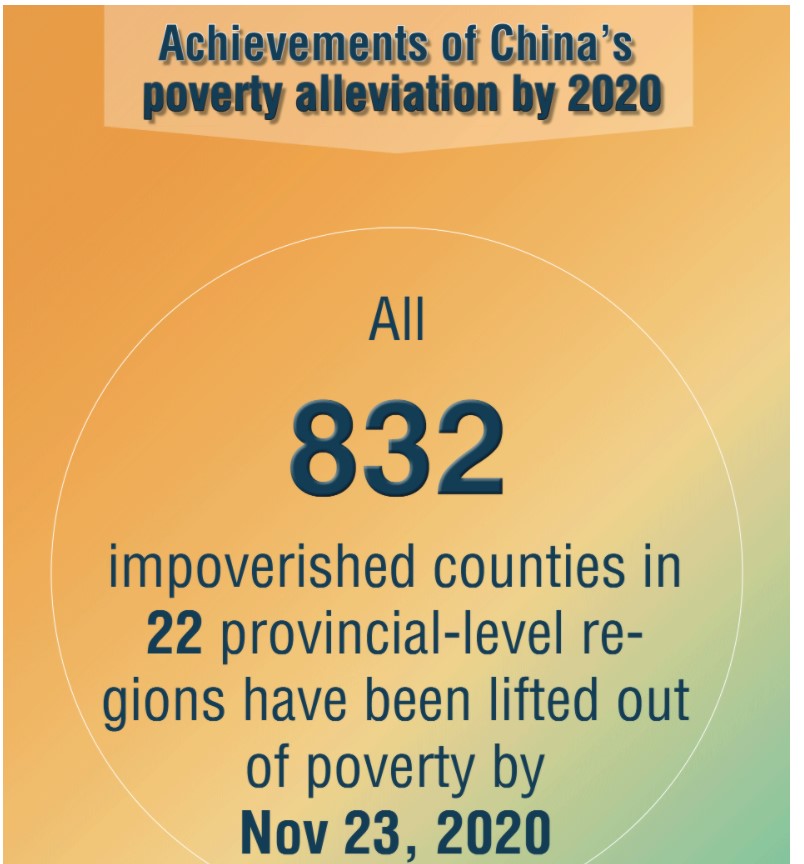

This applies also at modernity’s entry level, among those who have only recently had their “poverty hats” removed by decree of those who earlier designated them “poor.” On the ground in Tibet, China’s miraculous success in wholly abolishing poverty actually means, for the displaced/relocated, unending dependence on official handouts, since they are grounded, living in straight lines on urban fringes strung along highways, in accommodation too small to allow for any animals to be kept, unable to earn a living, all their accumulated landscape and pastoral management knowledge nullified and no longer relevant.

Yet Xi Jinping is triumphant, even while conceding the results are far from perfect. Xi says: “the CPC’s governing foundations in rural areas have been further consolidated. A large number of officials have been tempered in the fight against poverty, local CPC organizations in rural areas have seen their cohesiveness and effectiveness significantly enhanced, rural governance and management capacity at the local level has improved markedly, and the relationship between the Party and the public and between officials and the public has continued to improve. The success and experience that we have gained in poverty alleviation have contributed Chinese wisdom and solutions to the cause of global poverty reduction, demonstrating the political strength of the CPC’s leadership and China’s socialist system and winning praise from the international community. Many countries and international organizations have expressed their hope to benefit from China’s experience in poverty reduction. China is the only developing country that has simultaneously brought about rapid development and large-scale poverty reduction and enabled the poor population to share the fruits of reform and development. This is a miraculous achievement.”

This is the actual agenda: party building on the ground in Tibet, ongoing surveillance and supervision of the dislocated; and trumpeting of China’s miraculous achievement abroad.

However, in the fine print, Xi Jinping and the CCP’s internal disciplinarians concede that the miracle remains problematic. The pivotal year of 2020 climaxed an all-out assault on poverty measured by cash income, with announcements early that year, before the pandemic spread, of success in Tibet.

Since dislocations and vocational trainings are core strategies of poverty alleviation, and China’s rationale for mass punishment of Uighurs focusses on relocation and vocational education, there are now understandable fears that Tibet is going the way of Xinjiang. The January 2020 announcement that a further 19 counties in Tibet Autonomous Region had their poverty hats removed also announced: “A total of 155,000 people have received employment training and 186,000 people benefited from job placement projects supported by the local government, said Qizhala [Che Dalha] in his government work report delivered at the ongoing third session of the 11th People’s Congress of Tibet autonomous region.”[1]

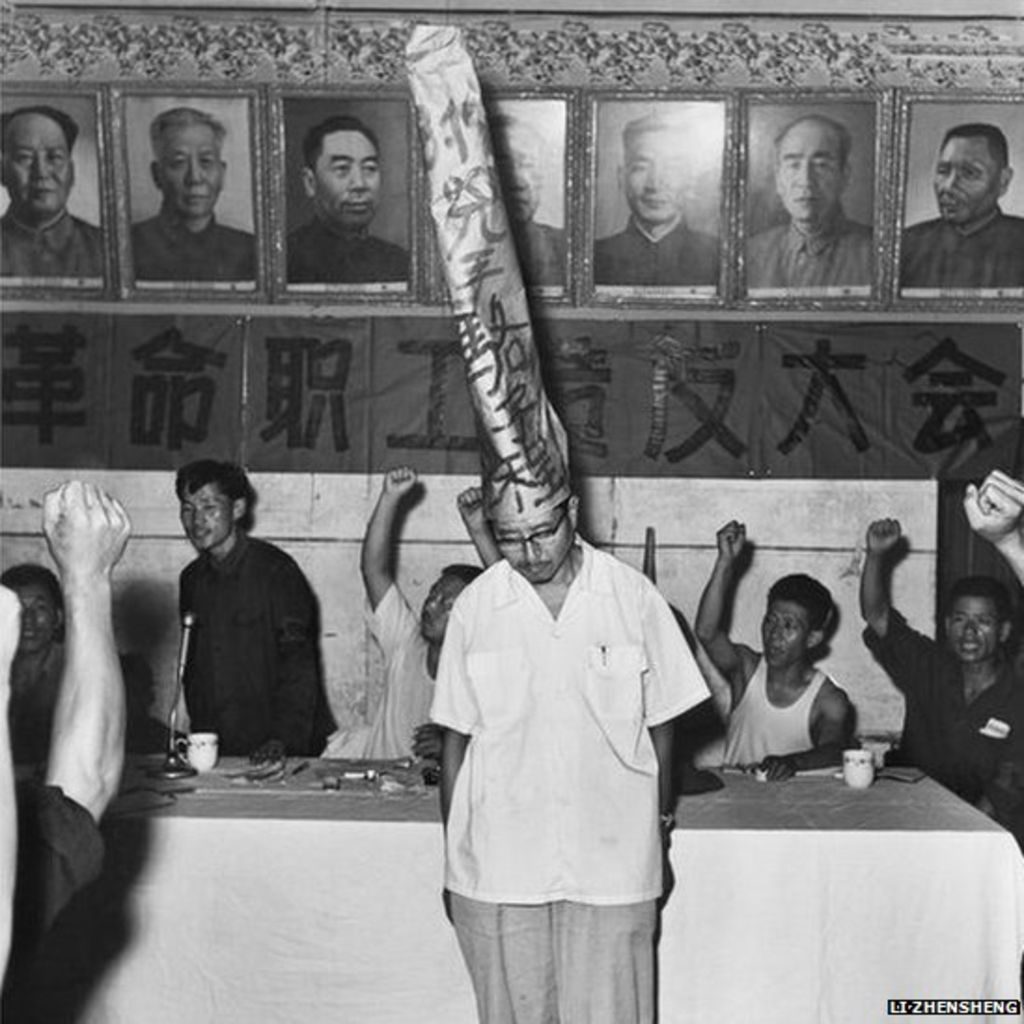

Whether such precise numbers are miraculous or alarming, they suggest rapid change, driven by military campaign urgency. Militarised language pervades Xi Jinping’s poverty campaign to prove the superiority of his new era China. In 2019 Xi concluded a long speech on poverty work: “Winning the fight against poverty is a historic mission that is both glorious and immensely challenging. If we are to attain complete success in this mission, we must continue putting in arduous efforts. We must press on with courage and resolve, making new and greater contributions so that we may realize our goals of winning the fight against poverty and building a moderately prosperous society on schedule.”

Campaign rhetoric condensed the targets into readily memorised mnemonics, such as the “three regions and three prefectures” singled out for special struggle; the three regions being southern Xinjiang and the entire Tibetan Plateau across five provinces; while the three prefectures are minority nationalities near Tibet. This closely fits the deterministic concept of “contiguous destitution areas” bereft of income because their natural circumstances are so utterly lacking in factor endowments.

Only months before Xi Jinping announced the miraculous achievement, an inspection mission sent from Beijing by the feared CCP Central Discipline Commission reported its dissatisfaction with how poverty alleviation was being done in Tibet. On 30 January 2019 CCDI published its findings, after interrogating officials across Tibet Autonomous Region, finding much at fault. Again their report is suffused with military metaphors. The report was delivered by Sun Yegang, who ran the Education Department in Xinjiang from 2004 to 2010, a period of intense assimilationist pressure to replace mother tonbgue languages with Chinese in all Xinjiang schools. [Byler, War on the Uyghurs 139-141] He was then promoted to be a CCDI leader. He had a long list of the failings of the poverty campaign in TAR:

“The shortcomings of industrial poverty alleviation are outstanding, and the performance of some fund projects is not high; there is still a gap in the implementation of the “provincial responsibility”, the overall coordination is not strong enough, and the main responsibility needs to be consolidated; the formalism and bureaucracy problems in the fight against poverty are not grasped. The tendency of focusing on traces and neglecting actual performance still exists; the grassroots party building still has the phenomenon of weakening and weakening, and the construction of the poverty alleviation team needs to be further strengthened; the publicity and education guidance is not in place, and the “helping aspirations” and “helping the intelligence” are still lacking; the discipline inspection and supervision organs pressure transmission Levels are weakened, some grassroots discipline inspection and supervision agencies do not handle clues in a timely manner, and some work is not strict and untrue; the supervision of functional departments is not in place, project and capital risks still exist; the overall research on the problems found in the rectification of various supervision and inspections is insufficient, and supervision and guidance Not strong enough.”

Sun Yegang demanded a more vigorous campaign in Tibet Autonomous Region that was better targeted, and better able to generate the intended result of haematopoiesis– the formation of blood cells in the weak, bloodless Tibetans immiserised by having to live in contiguous destitution. The feebleness of the Tibetans, in urgent need of either a Han blood transfusion, or training in anti-poverty haematopoiesis is a favourite trope of the party-state.

Sun Yegang, at the 19 Jan 2019 public release of the findings of the CCDI’s six weeks inspecting TAR, demanded seven “rectifications”, among them: “It is necessary to avoid “one size fits all” affecting the sense of gain of the people, and to prevent unrealistic policy formulation. Develop industries in accordance with local conditions, consolidate the results of poverty alleviation, and achieve long-term, stable and sustainable results in poverty alleviation.

“The fourth is to strengthen ideological guidance and stimulate endogenous motivation. In-depth study and comprehension of General Secretary Xi Jinping’s “Be the guardian of the sacred land and the builder of a happy home” in reply to the letter, deepen the “Four Stresses and Four Loves” activities, truly combine poverty alleviation with aspirations and intellectual support, and focus on the ability and self-development of the poor. Cultivate development potential and continuously enhance its own “haematopoiesis” ability.

“The fifth is to strengthen the work of party building to promote poverty alleviation, strengthen the construction of grass-roots party organizations, adhere to the combination of strict management and love, care for grassroots front-line poor cadres, and promote cadres to take responsibility.

“Sixth, we will further strengthen the supervision of the Commission for Discipline Inspection and Supervision and the supervision of the departments, gather the combined forces of supervision, intensify efforts to rectify formalism and bureaucratic issues, keep a close eye on the funds, key links and key areas of poverty alleviation projects, and carry out normalized supervision.

“The seventh is to consolidate the main responsibility of inspection and rectification, make overall research on the problems found in various supervision and inspections, find the reasons behind the problems, draw inferences from one another, establish a long-term mechanism, and use the actual results of rectification to ensure that the poverty alleviation task is completed on schedule.”

This is clear recognition that top-down, centrally designed programs delivered by cadres concerned only with fulfilling quotas and ignoring local concerns doesn’t work well. The solution is to double down on obeying central commands without the slightest deviation, yet somehow also avoid “one size fits all” and also develop industries in accordance with local conditions. Only then can those anaemic Tibetans shake off their poverty hats and grow some blood. The racist condescension is pervasive.

Sun Yegang adamantly insists this is all about politics, about boosting the power, reach and reputation of the CCP. Politics is everything. Explicitly targeting the relevant provincial party secretaries, he demands they “further improve the political position, implement the main responsibility for poverty alleviation, and earnestly assume the political responsibility of “provincial responsibility”, and regard poverty alleviation as a major political task and an important practical carrier of the theme education of “not forgetting the original intention and remembering the mission”.

China’s poverty “mission” is not primarily about “lifting” people out of poverty; it is about enhancing the party-state. To achieve this nation-building goal of turning an empire under alien rule in Tibet, into a unitary nation state, China dictates the lives and livelihoods of even its remotest citizens.

Starting with the Tibetan highlanders, specialists in making full use of the extraordinary efflorescence of alpine meadows in summer, China is leveling Tibet, bringing everyone down to the plateau floor. This is methodical, it has its own logic, and poverty alleviation is the primary rationale. China levels Tibet for the sake of those poor Tibetans stuck at altitude, condemned to eking a living in areas of contiguous destitution. By bringing the highlanders to the plains and into modernity, China manifests its’ benevolence.

LOOKING AHEAD

That’s the story this far. What of the future? Officially 2020 was pivotal, the year all poverty was abolished everywhere, and China officially attained its xiaokang goal of moderate prosperity. The modest goal to achieve xiaokang was announced by Deng Xiaoping in 1979, invoking an ancient Confucian trope. Now China has fulfilled its destiny.

In 2021 a new era beckons. For Tibetans, what matters most is what further plans China has, ready to roll out. What will happen to the massive bureaucracy mobilised to implement the poverty campaign? Are there more highlanders to be displaced and shunted into urban fringes? Will there be further campaigns to educate Tibetans displaced from their pastures, in how to become job-ready, having learned not only employable skills but how to overcome their “laziness” and accept factory assembly line discipline?

These are key questions, and we do have clear answers.

On 22 March 2021 new policies aiming to intensify production in rural areas throughout China were announced, in considerable detail. This includes the Tibetan Plateau.

In 2019 Xi Jinping named relocation as an ongoing agenda: “Construction tasks in alleviating poverty through relocation are nearing completion. During the 13th Five-Year Plan period (2016-2020), we planned to relocate about ten million people registered as living in poverty from inhospitable areas. By the end of last year, construction tasks related to the relocation of 8.7 million people had been completed, and most relocated people have been lifted out of poverty. We expect that the remaining construction tasks will be fully completed this year.”

Is relocation now fully completed? The 22 March 2021 “Opinion of the CCP Central Committee and the State Council on Realizing the Effective Connection between Consolidating and Expanding the Achievements of Poverty Alleviation and Rural Revitalization” answers this question. Although called an “opinion” of both party and state, it is a command, and is understood as such throughout China. It sets goals to be achieved during the 14th Five-Year Plan period, 2021 through 2025.

The goal has shifted. Rural revitalisation is a much bigger goal, in response to decades of frustration across rural China at widening urban-rural inequality. Past party-state pledges to reduce that gap achieved little. So now we get rural revitalisation/rejuvenation, 乡村振兴, a phrase aligned with a Xi Jinping favourite, the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.

The five years to 2025 are just the beginning of this great rejuvenation, which aims to apply productivist efficiency to the countryside, which means consolidating rural lands in fewer hands, intensifying production for urban consumption, making millions more small farmers redundant. Rural rejuvenation is the party-state’s embrace of the get-big-or-get-out logic of neoliberal capitalism; the same logic India’s Modi government embraced, then faced implacable opposition from farmers.

China’s small farmers lack any opportunity mobilise, unlike the Punjabis taking their tractors to town. Yet hundreds of millions of small farmers understand clearly that land consolidation makes winners and losers, so they will need years of persuasive propaganda to accept that selling their land rights to bigger players is the right thing to do. In theory, they are told, they can buy back those land rights.

Rural revitalisation, despite its sweeping ambition, is part of the urbanisation campaign, which targets much higher concentrations of people in cities in the foreseeable future. That’s the wider picture.

How does this affect Tibet? In the long term it could mean consolidating and intensifying rural production, especially meat production, which is what China most wants from Tibet these days. Several “livestock production industrial park demonstration zones” have been set up across Tibet, but so far on a limited scale, as Tibetans remain unconvinced that raising animals solely for slaughter is good.

However, this official “opinion” on Realizing the Effective Connection between Consolidating and Expanding the Achievements of Poverty Alleviation and Rural Revitalization is quite clear as to what can be expected in the next few years.

First, poverty may be officially gone, but there are many who could slide back, and the army of anti-poverty officials must remain on duty, forbidden transfer to easier jobs, mobilised for this new phase of fusing poverty alleviation with the wider agenda of rural revitalisation.

“By 2025, the achievements of poverty alleviation will be consolidated and expanded, rural revitalization will be promoted in an all-round way, the economic vitality and development potential of poverty-stricken areas will be significantly enhanced, the quality, efficiency and competitiveness of rural industries will be further improved, the level of rural infrastructure and basic public services will be further improved, the ecological environment will be continuously improved, the construction of beautiful and liveable villages will be solidly promoted, the construction of rural civilization will make remarkable progress, the construction of rural grass-roots organizations will be continuously strengthened, the long-term mechanism of classified assistance for rural low-income population will be gradually improved, and the income growth rate of farmers in poverty-stricken areas will be higher than the national average.”

The poor have now entered history, are on the road to civilisation, poverty alleviation is morphing into development, an urban future for most rural dwellers beckons. This conforms to universal laws of development, in China’s official eyes, an inevitable progression from poverty to accelerated income growth rate, from backwardness to human quality, from darkness to light in an urban apartment block. These are the common metaphors of party-state “opinions” and “guidelines”.

As always, the civilising mission is arduous. Poverty is notoriously intermittent, in Tibet much dependent on seasonal variability. Backsliding must be prevented.

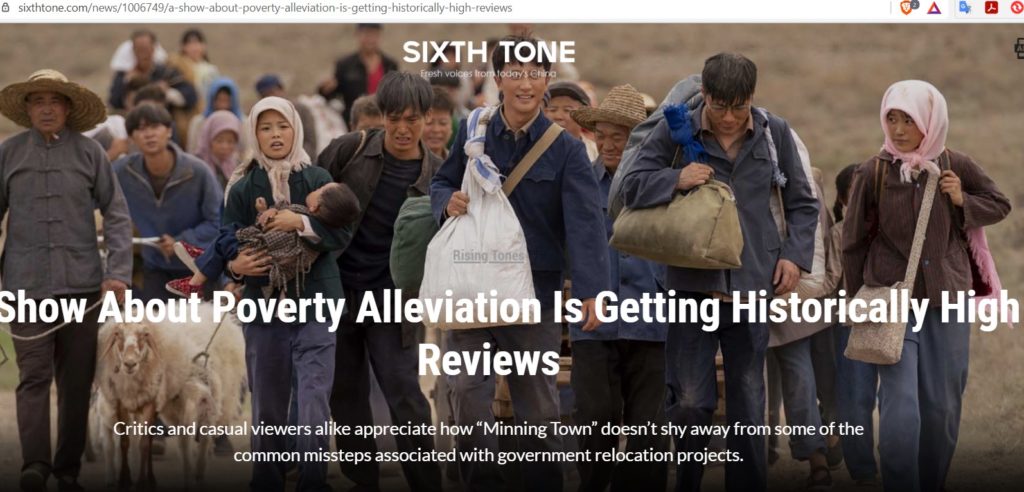

China’s benevolent blood-strengthening poverty alleviation programs have been skilfully popularised by the recent Minning Town tv drama series, set in Ningxia, an arid inland province nominally for Muslim Chinese, where the human footprint has outstripped the capacity of the land to support the population. In 23 long episodes the drama unfolds. This is a production with a huge cast, six scriptwriters, two directors, a big budget and believable plotlines that don’t feel at all like the stiff propaganda language of those official “opinions” above.

Spread slowly and believably across so many eps, the story deeply engaged a wide audience. Already all eps are on YouTube, with subtitles, or you can read a plot summary on China’s Wikipedia, Baike Baidu.[2] Minning Town, newly built to relocate the poor as desert encroaches, is a success, despite many setbacks, because central leaders in their paired wealthy coastal Fujian province with destitute, arid, inland Ningxia. The Chinese name of this long form drama is Shanhai qing, connoting the bringing together of the mountains and the ocean, Ningxia and Fujian, learning to love each other. The Fujian experts sent to uplift the relocated villagers teach them how to grow mushrooms, then how to successfully market them. All ends well. The relocated are indeed grateful.

But do the Tibetans perform the correct gratitude for China’s civilising mission? Can Tibetans bring themselves to endorse the extravagantly self-congratulatory language of the 22 March announcement:

“The great practice of poverty alleviation has fully demonstrated the great miracle created by our party’s leadership of hundreds of millions of people in adhering to and developing socialism with Chinese characteristics, and fully demonstrated the political advantages of the leadership of the Communist Party of China and my country’s socialist system. Getting rid of poverty is not the end, but the starting point for a new life and a new struggle. After winning the battle against poverty and building a well-off society in an all-round way, we must do a good job in rural revitalization. In order to focus on realizing the prosperity of rural industries, ecological liveability, civilized rural style, effective governance, and affluent life. The focus has been shifted from focusing resources to support poverty alleviation to consolidating and expanding the results of poverty alleviation and comprehensively promoting rural revitalization.”

Achieving all of this escalating agenda will be difficult, with many dangers to be avoided. One danger neoliberals in China and elsewhere worry about is “avoiding policy settings that subsidise lazy people or encourage long term welfare dependency”, 防止政策养懒汉和泛福利化倾向, Fángzhǐ zhèngcè yǎng lǎnhàn hé fàn fúlì huà qīngxiàng.

This is especially pertinent to Tibet, where cadres have for decades accused Tibetans of being insufficiently desirous of consumer goods, stubbornly unwilling to relocate, uncompetitive and uninterested in accumulating wealth as an end in itself.[3] The pedagogies of the party-state have only slowly shifted Tibetan thinking towards commercialisation, intensification and productivism. The phrasing of this 2021 “opinion” is ominous.

How to achieve the new 2025 goals? This requires a tricky balance. On one hand state transfer payments to the newly unpoor must continue, lest they backslide, but without promoting laziness. How to tell? Ongoing intensive surveillance is the way: “Give full play to the advantages of concentrating forces on major events, and extensively mobilize the participation of social forces to form a strong joint force that consolidates and expands the results of poverty alleviation and comprehensively promotes rural revitalization. Supervision to prevent poverty rebound. The continuation of the existing assistance policy, the optimization of the optimization, and the adjustment of the adjustment ensure policy continuity. Relief policies must continue to maintain stability. Improve the dynamic monitoring and assistance mechanism for preventing the return to poverty.

“Regular inspections and dynamic management are carried out for households that are out of poverty, unstable households, marginal households prone to poverty, and households experiencing serious difficulties in basic living due to large expenditures due to illness, disasters, accidents, etc. Establish and improve the rapid detection and response mechanism for the poor who are prone to return to poverty. Establish a mechanism for discovering and verifying people who are prone to return to poverty, which combines active application by farmers, departmental information comparison, and regular follow-up visits by grassroots cadres, and implement dynamic management of assistance targets. Adhere to the combination of preventive measures and post-event assistance, accurately analyse the causes of poverty caused by returning to poverty, and adopt targeted assistance measures.”

This is why the army of cadres mobilised to scrutinise Tibetan lives and assess their compliance cannot be stood down, nor permitted to apply for more comfy urban jobs. Rural Tibetan lives must be legible to the gaze of the state, to determine whether they can take off their poverty hat or not. Scrutiny leads to decisive state intervention when required, especially in areas of contiguous destitution.

Relocations are not over at all; displacement remains a key policy solution: “Do a good job of follow-up support for relocation of poverty alleviation and relocation. Focus on the original deeply impoverished areas and large-scale resettlement areas, increase support in terms of employment needs, industrial development and subsequent supporting facilities construction and improvement, improve the follow-up support policy system, continue to consolidate the results of relocation and poverty alleviation, and ensure the stability of how the relocated people can live, have employment, and gradually get rich. Improve the level of community management services in resettlement areas, establish a caring mechanism, and promote social integration.”

Getting rich, measured as cash income, is the only permissible outcome, and the party-state cannot begin to imagine relaxing its grip until this is achieved. Relocation is only a first step in a trajectory that then requires employability training and industrialisation.

In order to achieve that goal, not only must Tibetans be intensively monitored, but the monitors in turn must also be monitored to ensure compliance. The party’s Central Commission for Discipline Inspection, after inspecting Tibet Autonomous Region made it clear in 2019 they will stay on the case: “Persist in comprehensive rectification, implementation and reform, immediate improvement when knowing, real reform and actual reform, regular reports on the rectification situation, and the formation of a regular and long-term mechanism for rectification and reform. Disciplinary inspection and supervision agencies and organizational departments should strengthen daily supervision of inspections and rectifications, and urge inspections and rectifications to be effective; combined with the problems found in inspections to deepen special governance, focus on rectifying formalism and bureaucratic problems; improve the quality of supervision to prevent generalization and simplification of grassroots accountability ; Serious accountability for ineffective rectification, perfunctory response, and false rectification, and the requirement of comprehensive and strict governance of the party throughout the entire process of poverty alleviation.”

Language like this is these days common, a florid display of loyalty to core leaders, a repeat of solemn pledges made many times before. But gradually the pressure on Tibetans to leave their highlands, to embrace money making, to get rich, to become Chinese, grows and grows. Gradually Tibetans are incentivised to become dependent on the state for secure lifelong “iron rice bowl” employment. This includes employing drogpa nomads -one per family- as park rangers responsible for policing compliance with relocation orders. Gradually the budget for retraining the “lazy” Tibetans to become more competitive increases. Gradually schooling is extended to preschool kindergarten years, with Chinese the medium of instruction. Gradually the pressure on Tibetans grows.

http://www.ccdi.gov.cn/yaowen/201901/t20190128_187862.html

The 2020 announcement that poverty is ended has been followed in 2021 by massive self-congratulatory celebrations staged by the party-state to make sure everyone gets the message. This includes the presumption, deeply embedded in China’s networking culture of gifts, favours and banquets, that recipients of gifts should display the proper gratitude. The ingratitude of the Uighurs for China’s gift of development in Xinjiang was a driver of the punitive fury that now engulfs Xinjiang. Tibetans too are not displaying sufficient gratitude for having been saved from Tibet, by relocation and a one-way ticket into the urban factory workforce. Xinjiang was industrialised much more than Tibet, so it’s far from an exact parallel, and there are plenty of videos in official media in which Tibetans do display the mandatory gratitude for poverty alleviation.

Will China tilt into fury at Tibetans too? It is possible, yet the Tibetans, despite being depicted as poverty-stricken primitive tribals, have so far managed to avert such extremes.

[1] Tibet helps 150,000 shake off poverty in 2019, Xinhua, 7 Jan 2020 https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202001/07/WS5e143cfca310cf3e3558301e.html

- [2] https://www.youtube.com/watch?reload=9&v=l8dv_IepPWg&feature=emb_logo ep 1

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Tr9sTT_D_0 ep 2

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0c0DKBkjaSo ep 3

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZB4B5arN75s ep 4

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dXzpn5F2ADU ep 6

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZGHj0_txuyE ep 8

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3bTpZ1DTX48 ep 12

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CFOjxpHHi-8 ep 16

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AKCjC4yluEE ep 17

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UxufALev9Qo ep 23

[3] Xiaoqiang Wang and Nanfeng Bai, The Poverty of Plenty, Palgrave, 1991