Blog one of two on China’s latest plans for upscaling poverty alleviation in rural Tibet towards urbanisation, industrial agribusiness, commercialisation and accelerating the speed of life.

Apparently, China is shunting Tibetans out of their pastures and into the global economy of factory workers, a planetary underclass of underpaid, insecure assembly line workers; so China tells us.

In official Chinese eyes, that’s progress, the march of modernity, entry of the timeless Tibetans into history and the relentless speeding up of production, consumption, life and death. Although Tibetans are inclined to see this as a degenerate age, of reduced attention spans and innumerable distractions, the world has repeatedly congratulated China on “lifting” hundreds of millions, including Tibetans, out of poverty.

Although, by decree, poverty is now at an end throughout China, the party-state now wants more applause, and is embarking on a massive program of “rural rejuvenation” which shunts not only Tibetans but rural Chinese about the landscape, to fit them into new lifeways in cities and factories.

This is the new post-poverty agenda, officially revealed 22 March 2021 in a joint announcement by both branches of the party-state, the Chinese Communist Party and the State Council. This is the next big step, to remould, consolidate, intensify and accelerate the countryside, especially the remotest and poorest districts least able to resist.

China tells the world it has already built a miracle in Tibet, sparing no effort to lift all Tibetans out of poverty, and there is more mass relocation to come.

China is unique in expanding resettlement way beyond those immediately displaced by dam construction and other infrastructure projects. Building on a long history of pushing the poor into pioneering China’s new frontiers, China today does not hesitate to engineer development by pushing the poor to geographies where development is to occur.

A recent overview of China’s ambitions finds: “Unlike other places where resettlement is largely a by-product of large infrastructure projects, in China resettlement is used as a tool for poverty alleviation. With the introduction of Xi Jinping’s Targeted Poverty Alleviation, and the goal to end absolute poverty by 2020, resettlement has become central to China’s poverty-alleviation practice. Rather than investing in dispersed, remote villages, the Chinese government prefers to bring people to development by constructing high-density resettlement sites in small towns and peri-urban areas: up to 16 million people are being resettled between 2016 and 2020.

“China’s intense focus on resettlement as a tool for poverty alleviation has resulted in reduced financial burdens on those resettled, but is also engendering new conflicts at the local level. Our analysis highlights the contested nature of state-driven resettlement for poverty alleviation and raises questions about the relevance of this practice for other developing countries.”[1]

A BACKSTORY OF RURAL DISCONTENT

For decades rural China has complained of being left behind in the rush to get rich, their only options being labour migration to the cities, or selling their land, if nearby expanding towns, to local governments which then profit massively by rezoning agricultural land bought at agricultural prices, as urban land for apartment towers that often rehouse those just displaced from their farmland.

Neither of these two choices are appealing. When the fittest young adults move to seek factory jobs in cities and the industrial parks that surround so many cities, they must submit to corporate discipline, and if injured, go back to the village without compensation. They cannot bring their kids with them, since city schools won’t admit them, or elderly parents, since city health services won’t treat them. But if they stay on their land, and the local government wants it for urban expansion they have to sell, for farmland price, ripped off by those who supposedly represent them.

This has gone on decade after decade, as the urban-rural wealth gap has widened further, likewise the east-west gap, the Han-minority minzu gap, and the tuhao (new rich)- nongmin (peasant) gap. For decades the party-state has promised to reduce these gaps, and has made dramatic but empty gestures such as ensuring that the Number One official party-state policy announcement each year is on rural affairs.

To those focussed specifically on Tibet, this might seem only marginally relevant, especially at a time of alarming reports of mass mobilisation of Tibetans into labour mobilisation programs and then factory work.

However, the wider context matters. The party-state insists its policies fit all, and are to be implemented everywhere in the same way, with only minor adjustments for local circumstances. So if we want to evaluate labour mobilisation in Tibet, we need to see how that fits the national “post-poverty” agenda of rural revitalisation. It’s not only Tibetans who get shunted; treated like chives to be cut at the whim of the powerful and expected to just grow back. Throughout China villagers call themselves chives to be knifed at any moment, so deep is the history of shunting people about for reasons of state.

A CAMPAIGN WAGED BY MASS MOBILISATION OF CADRES

Proving the superiority of the China model has long included mass mobilisation campaigns to raise remote rural incomes above an artificially low poverty line. China’s self-proclaimed 2020 success in removing the “poverty hat” from every designated poor county across China and Tibet, is proof of the superiority of socialism with Chinese characteristics, in contrast to the capitalist West.

The decree that poverty anywhere had been ended in 2020 culminated a massive effort that took many years, with a huge number of cadres, especially at local government level, involved in the “arduous struggle” to save the poor from themselves. A high proportion of officials have been involved in projects to identify specific poor families, document the causes of the poverty, and come up with officially sanctioned new sources of income, often requiring emigration. Poverty alleviation became an industry. The official, triumphant 2020 announcement that all poverty is hereafter abolished was followed, by what? He complex bureaucracies at national, provincial, prefectural, county and township levels dedicated to leading the fight against poverty: what was to become of them?

There are four interconnected reasons why the post-poverty rural rejuvenation/labour mobilisation campaign is ramping up.

- China’s international reputation, throughout the developing world, as successful in lifting all out of poverty and onto the road to wealth, enhances China’s claim to uniqueness, and to superiority over the capitalist West.

- Social unrest against injustice, disempowerment, corruption and exploitation of rural areas is so widespread something beyond slogans had to be done; and “rural rejuvenation” strategy aims at intensified land ownership and scaled up production.

- Without abolishing the hukou household registration certification, rural workers who are no longer needed on the land, as scale and technologies replace humans, will emigrate to cities. There they will replenish a dwindling industrial proletariat, be intensely surveilled at work and in their new apartment blocks, and China’s extreme concentrations of wealth can persist.

- A politicised bureaucracy is repurposed from poverty alleviation to post-poverty control over access to official permissions, resources and finance, extending party-state control deep into the lives of the millions who will continue to depend on state allocated transfer payments. The gaze of the state, into the lives of its scrutable, repackaged, newly urbanised citizens is extended.

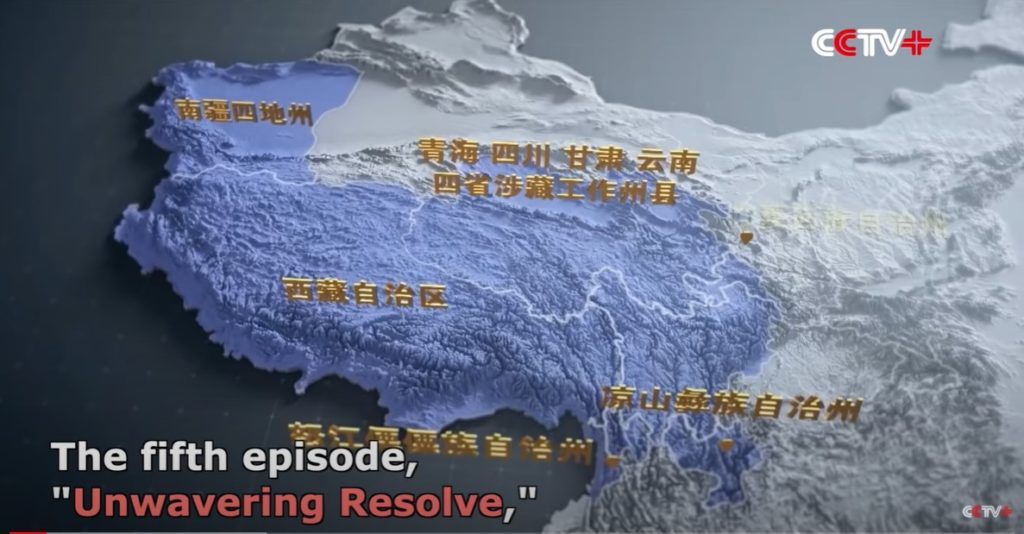

All four reasons for ongoing manipulation of rural lives also affect Tibetans, in all five Chinese provinces where Tibetans live in legally autonomous regions, prefectures or counties. Perhaps Tibet is not only affected; it may even be on the front line, as rural rejuvenation/revitalisation rolls out. China in high assimilationist mode turns to social engineering on a large scale.

This blog looks into those impacts in Tibetan areas, and in so doing, contextualises those alarming suggestions that Tibetans have already been retrained, re-educated and shipped off as surplus labour, on a large scale.

To understand what is happening in Tibet, and is likely to happen soon, we need to understand what China’s key policy decrees mean for all of China; and we need to see how and why Tibet is at the forefront. For China’s grand strategists the sheer size of the Tibetan Plateau makes social engineering a temptation, and a necessity if rural Tibet is to be remade as Chinese, oriented towards lowland China, assimilated into a single identity. Experiments in social engineering, driven by official fascination with “top-level design”, are especially attractive when they can be done on a large scale, as in Tibet, with little that can get in the way. Tibet is a giant sandpit, for playing with engineering the human soul (a Stalinist phrase still in use in China). Tibet is a laboratory for real-world experimentation with new social structures, that can later be introduced across China, and around the world.

REMAKING TIBET IN CHINA’S IMAGE

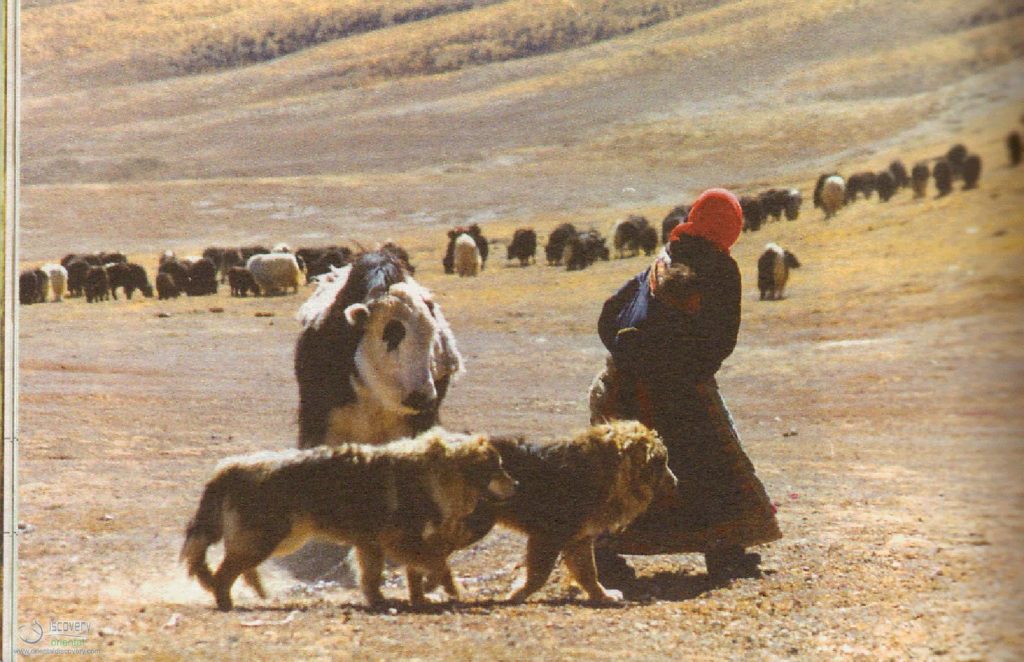

China has powerful incentives to reshape Tibet, and to inscribe it with Chinese characteristics, in ways not possible until now. Unlike Xinjiang in recent decades, and unlike all of southern China in recent centuries, Tibet is not amenable to mass settlement of Han emigrants. China tried “reclaiming waste land” in Tibet, meaning ploughing grassland and sowing Chinese grains and other crops, which did not succeed in Tibet’s frigid climate. Without crops, mass migration of poor rural Chinese into Tibet was not possible.

Now the Tibetan Plateau faces a quite different path to full assimilation into China, a path which combines enclaves of intensive resource extraction, industrialisation and urbanisation; with huge areas repurposed as pristine wilderness for tourist consumption. The Tibetan population, customarily spread thinly over innumerable plateaus practicing extensive land use, is to be concentrated into enclaves, leaving vast landscapes unoccupied, available for inscription as China’s mysteriously fascinating back yard, a natural gem in China’s grasp.

Tibet, having been a laboratory for experimenting with new models China hopes can become exemplary, may emerge as a propaganda success story for emulation, both across China and around the developing world. The prospect is that Tibet can be both modern and prehistorically pristine, developed yet timeless, prosperous yet also archetypally restorative landscape for tourist recovery from urban stress.

MODELLING CONFUCIAN PROPRIETY

Kathryn Gomersall argues that China’s 2016 campaign to Build a New Socialist Countryside (BNSC) relies heavily on models. More so the 2021 rural revitalisation agenda: ““Models” are a Confucian technology through which the moral example is disseminated throughout society. Model villages are constructed to act as a guide for all other villages to emulate. They serve the purpose of governing behavioral norms and the social order through moral regulation as well as physical and social structures that organize rural life. “Improvement” through aspiring to the example, mobilizes people and hence drives the success of the governance system. Models are therefore used in image building and as a propaganda tool to depict an envisioned future for rural China. BNSC models elicit a resurgence of Communist style “showcasing” in which favoritism guides policy implementation. In this way, they provide opportunities for various actors such as promotion, embezzlement or preferential treatment as a result of qualification of model status. Officials experiment with policy implementation to identify successful local systems to be emulated across the county.”

Part of that experimentation by local officials invokes Confucianism as a technology of governance, used to ensure compliance within villages that the party-state decrees are to be resettled as part of the poverty alleviation agenda, usually on the grounds that poverty is inherent in the landscape and is thus ineradicable as long as villagers live in villages that, in the gaze of the state, are shamefully remote, primitive and embarrassing to a great power. These are the areas designated as “contiguous destitution” geographies, 个集中连片特困区贫困, a stigmatising category of official thinking which attributes limited cash incomes among subsistence farmers as a direct outcome of the perverse choice of villagers to live in such bereft landscapes, defined in official eyes by their lack of factors of production.

Gomersall did her fieldwork downriver from Tibet, in Shanxi, where villagers have long carved well insulated dwellings out of the deep, soft loess silt soil the Yellow River erodes from Tibet. The party-state, with patriarchal hauteur, calls them cave dwellers. “The rationale of poverty alleviation resettlement (PAR) prescribes criteria for equitably selecting recipients for assistance based on remoteness and lack of access to resources and services. These criteria also make a latent rural labor force visible and calculable to a state apparatus engendering a neoliberal governance regime. Tensions were evident in Tao village during the selection process due to the contradictory nature of policy implementation.”

Local government cadres make themselves a permanent presence in the lives of remote villagers as never before, with power to draw on the distributive capabilities of an allocative state, and power to decide who qualifies for transfer payments, and who must leave for resettlement elsewhere. Despite China’s long history of authoritarian government, seldom has the state been so present in the lives of villagers, especially the poor.

THE POOR ARE ALWAYS ABOVE US

In Tibet, the highest priority for resettlement is those who live above the plateau floor, in the hills between the plateau floor flat pastures below and the bare rock of the high country above the tree line. On south facing hillsides alpine meadows do flourish in summer months, so abundantly that herds driven upslope are unable to exhaust the bounty of herbs and grasses; but China has selected Tibet’s hill people as especially benighted, incurably poor with no prospect of redemption as long as they stay up in the long winding valleys in the hills. Altitude is the state’s criterion, triggering compulsory relocation, from the top down.

Hilly terrain and the logic of extensive grazing customarily make for scattering the upland pastoralists, the opposite of concentration. In the gaze of the party-state this low density and nomadic mobility are suspicious, beyond the scrutiny of the state, allowing nomads to tuck animals away in remote valleys, avoiding the counting done by livestock inspectors sent to check that official stocking density numbers are being obeyed.

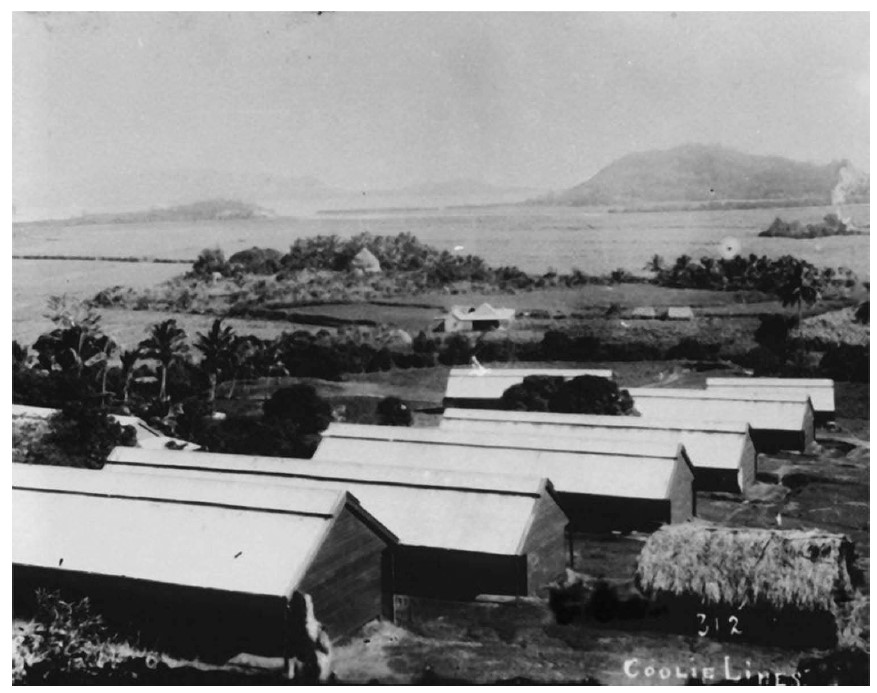

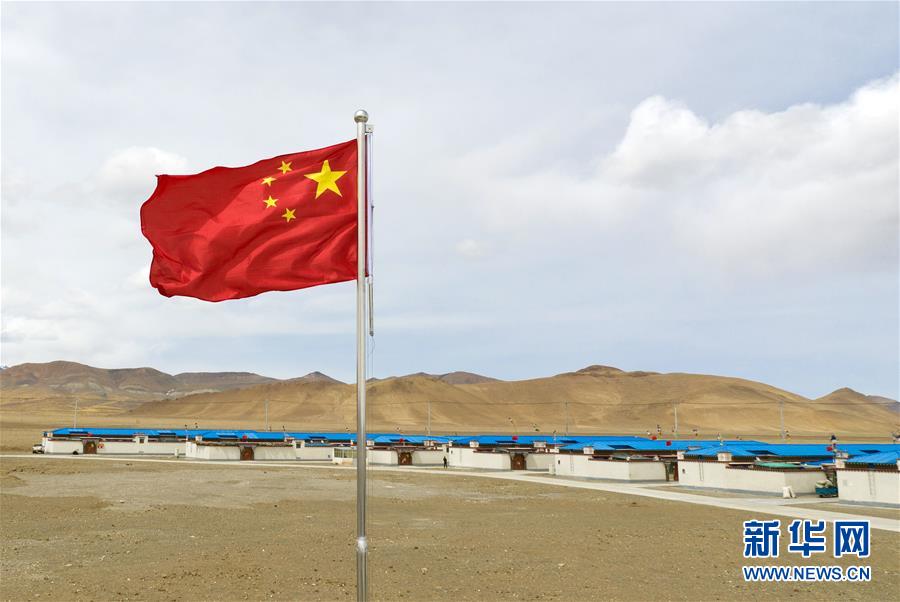

GEOMETRICALLY LINING UP THE RELOCATED

When hill Tibetans are resettled it is invariably in invariable straight lines, along roads, in neat geometric lines of concrete housing. These are the new line villages, the straight lines signalling more than scrutability, countability and concrete comfort. The line village is Civilisation 101, an induction into the universe of civilised behaviours, some of which are explicit, such as injunctions to no longer spit, to wash regularly, to use modern toilets, the agendas of hygienic modernity.[2] Many of the expectations and requirements of the party-state are not as explicit, yet bear heavily on those now, for the first time, lined up. Adrian Zenz has collected many phrases used in official documents: “Poverty alleviation reports bluntly say that the state must “stop raising up lazy people.” Documents state that the “strict military-style management” of the vocational training process “strengthens [the Tibetans’] weak work discipline” and reforms their “backward thinking.” Tibetans are to be transformed from “[being] unwilling to move” to becoming willing to participate, a process that requires “diluting the negative influence of religion.”

The line village is a classic coloniser’s move. In New Guinea the colonial administration prioritised bringing down to the plain’s villagers up high in the jungle-clad mountain slopes, insisting they henceforth reside in line villages, even though malaria was much more common than in the mountains.

Similarly, in Fiji, where the British colonisers shipped in Indian indentured labourers to work the sugar cane fields, the Indian “coolies” had to live in lines: “Each plantation had designated lines where their indentured labourers would live, and, in turn, free settlements would spring up once labourers completed their tenure and moved off the plantation. In Fiji, the landscape of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century of billowing green cane fields, orderly coolie lines, haphazard free Indian settlements, and isolated native villages was the result of a commodity trade that linked Fiji into a global economy. Accommodation was organized into lines, as it was in other colonies which had not previously had a sizeable slave labour workforce such as Assam, Ceylon, and Malaya. The use of terminology such as ‘lines’, in the same vein as the usage of ‘colony’ and ‘quarters’, became a colonial practice that characterized those parts of a plantation where labourers were housed. Lines enabled ‘the desired positioning of bodies and spaces’ which was essential in creating a functioning and efficient plantation economy. The lines were to contain nurseries and latrines, and the keeping of animals was prohibited. They were to be an ordered space, by their very nature artificial and regimented, barrack-like in appearance. The very language used to describe housing in Fiji –lines – conjured up the effect that these were not organic settlements where social life could play out naturally – they were there for the sole purpose of accommodating labourers in the most practical way possible.”[3]

China, over a century later, has managed to reproduce this paternalistic ordering of the unruly. As in the British colonies, the intention is to discipline workers into industrial worklife.

THE POOR DWELL ALSO IN CAVES

In China, those designated as highest priority for resettlement are not only upcountry Tibetan pastoralists but also villagers in several provinces who have found it convenient to live in caves in the hills. In the metropolitan gaze this is primitive, even if, as the cave dwellers tell us the caves are well insulated, dry, and don’t rely on central heating being switched on as winter sets in, on a set day, irrespective of the cold seeping into the bones of the elders. Chinese citizens living in caves are the epitome of all China, as a great power, leaves behind as an embarrassing past. Even when the caves are carved from the soft silt of the loess, it’s primitive.

In recent years, official media have reported from cave villages all over China the welcome ending of primitivity, as cave dwellers emerge into the light of modernity and the line.

Kathryn Gomersall did her fieldwork among the Shanxi cave villagers as they went through the bureaucracy of resettlement. We can learn much from her ethnographic observations. What she observes is valid for Tibetans now being herded downslope and into the new line villages.

China’s official distaste, even horror, that 21st century Chinese citizens could live in caves is palpable. An official publication from populist China Pictorial tells us: “These people formerly lived in cold conditions, lacking water, electricity and roads; landslides were frequent, and diseases were widespread. Many even lived in caves and shacks. Now they have moved into new homes with easy access to facilities. Their quality of life has improved greatly.”[4]

In vain do the relocated protest that their cave homes are comfortable and well insulated; and they would prefer not to have to move to centralised housing under centralised control. Among the many videos China’s official media publish praising the end of cave dwelling, one video, not from official media but Turkey’s TRT, stands out. An older woman dreads leaving her cave for the bureaucratically timed seasonal firing up of central heating well after the encroaching winter chills her bones. For her, the loss of her cave home is a loss of freedom and choice. Such voices are not to be heard in Chinese media.

A similar horror pervades the official concept of contiguous destitute areas 个集中连片特困区贫困 Gè jízhōng lián piàn tèkùn qū pínkùn. This classification of multiple landscapes and entire counties, especially in Tibet, solidifies many habitual Chinese assumptions, conflating the air of Tibet (too thin, too cold), Tibetan soil and vegetation (too unproductive and slow to grow), the sheer size of the Tibetan Plateau (too vast and remote), and the Tibetans who perversely choose this as their homeland (too ignorant and lazy). “Areas of contiguous destitution” manages to package a whole spectrum of Chinese misunderstandings and failures to learn. The concept provides all the excuses needed for why it is taking so long to end poverty in Tibet, also in the cave villages and other remote districts. It makes the resettlement of the contiguously destitute necessary and inevitable, by reifying prejudices as objective facts. China relocates such folk for their own good, even if backward folk don’t know what is good for them.

In the eight-part documentary series aired on official media in March 2021, celebrating the end of all poverty “on schedule”, episode five focusses on the entire Tibetan Plateau and southern Xinjiang as arduous CCP struggles to complete the miraculous abolition of poverty, including the switch to teaching children only in standard putonghua Chinese. The episode is called Deeply Rooted in the Rocks, which is a bit more poetic than “contiguous destitute areas”.

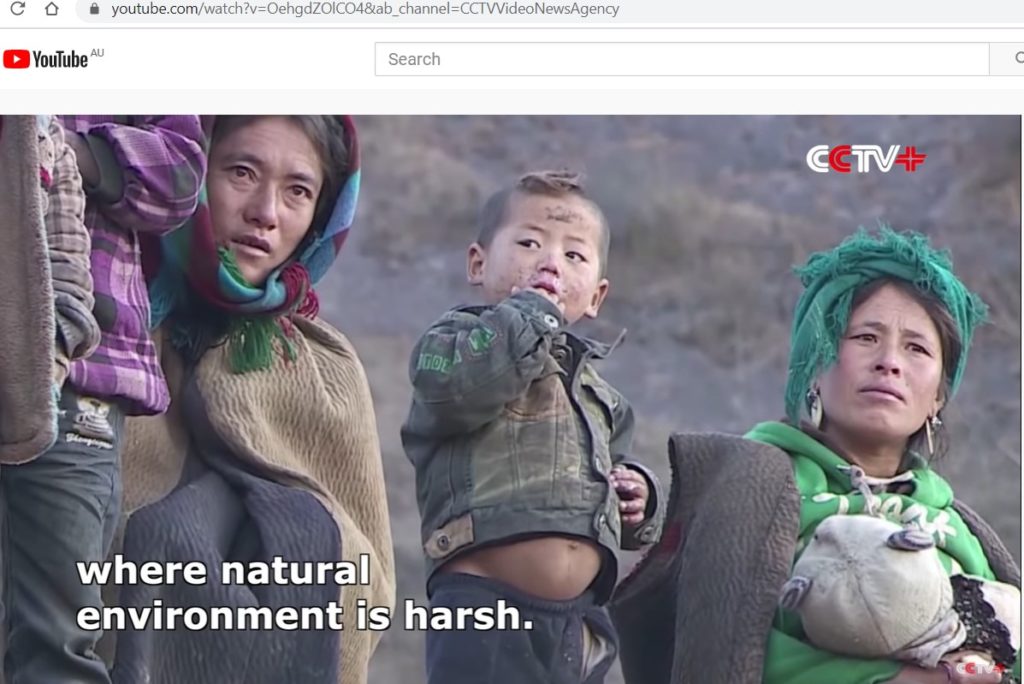

DEFINING TIBET BY WHAT IS LACKING

The metropolitan gaze sees only lack: “in the Qinghai-Tibet plateau where natural conditions make living extremely harsh, and in the drought areas of the Northwest, desertification areas, karst areas, mountainous areas, border areas, life is hard for local residents, economic development is sluggish, public services are poor, and residents suffer from local diseases. The fight against poverty is a difficult one, confronted by many challenges.”[5]

That was a decade ago. Now there is officially no more poverty anywhere in China. The target set by Xi Jinping of 2020 as the final abolition of all poverty was met, and profusely celebrated by the party-state. Tibet was officially the first to fully abolish all poverty, in the first month of 2020, before corona virus took over as the global focus. Every one of the 150 counties classified as “Tibetan autonomous”, across five provinces, all took off their shameful “poverty hats” that had stigmatised them as contiguously destitute. Shaming the wicked and the losers by making them wear a big, pointed hat announcing their failures is an old tradition, much used during the Cultural Revolution.

Since the foundational premise of poverty alleviation is a reified package of prejudices, it is hardly surprising that the solution invariably requires relocation, sometimes not far, but more often to a quite different landscape, a much more Chinese urban landscape. By defining Tibetans as lacking all that is civilised it follows logically that they must move to where factor endowments naturally cluster.

Bundling prejudices masks agendas. By defining poverty solely as a list of lacks inherent in the landscape, the party-state conceals from itself what actually drives the anti-poverty campaign, which is about presenting China in the global gaze as modern, inclusive, successful, leaving no-one behind, uniquely capable, clearly different to the capitalist West. The anti-poverty campaign is about brand management, of China as different and superior.

PRECISION POVERTY TARGETING

Bundling arrogant assumptions also makes it easier to define anti-poverty work as targeted, specific and accurate, based on objective data that conceal the stigmatising prejudices. Xi Jinping made the poverty campaign a top priority, enabling 2020 to be declared China’s entry into a new era, with new utopian goals, on the basis that old tasks had now been completed.

In 2015 Xi Jinping announced the five-year goal of totally abolishing all poverty, and as 2020 approached, he made it a top priority, and success mandatory. This mass mobilisation campaign within the party-state apparat was an enormous undertaking, requiring millions of officials to prioritise poverty among their many duties. In 2019 Xi Jinping provided precise numbers: “To identify who should implement poverty alleviation initiatives, we have selected more than three million officials from government departments at or above the county level and from state-owned enterprises and government-affiliated institutions to serve as village-stationed providers of support. Currently, there are 206,000 first secretaries of CPC village committees and 700,000 village-stationed officials, in addition to 1,974,000 town-level poverty alleviation officials and millions of village officials. We have thus significantly bolstered our forces on the front lines of poverty alleviation, and ensured that our efforts in this regard overcome final key hurdles.”[6]

This army of officials empowered and commanded to intervene in the lives of remote villagers and nomads is now an asset of party-state power not to be dissipated, as it extends the reach of the state into intimate details of daily life, enabling the official gaze to scrutinise and then correct the thinking as well as the behaviours of the objects of poverty alleviation. Never before has central authority had such access to private lives, or been able to make family dynamics so legible.

Eliminating poverty crucially depends on how poverty is defined. In China the definition is purely monetary, set at under RMB 3000 per person per year. At official exchange rates that’s around US $460 a year, but RMB3000 buys you a lot more in China than US$460 does in America. Nonetheless, this definition sets the bar real low, making victory so much easier. If you ask rural Chinese across China for their own definition, you get a very different result. A team of Chinese researchers from the Centre for Chinese Agricultural Policy of the Chinese Academy of Sciences did just that in 2016, going to five representative provinces, asking over 2000 rural households to gauge, from experience, what income is required to not be really poor. Their conclusion was that the poverty line is actually RMB 8297, about three times the official definition.[7]

China has a long history of shunting people around, such as the mass demobilisation of PLA soldiers sent to Xinjiang after the CCP victory in civil war in 1949, and ordered to stay there to build state farms under paramilitary control. The last thing a newly established revolutionary government wanted was a population of unemployed ex-soldiers in Beijing, on the loose.

But the program of “precision poverty alleviation” keeps those relocated under surveillance, data on their behavioural compliance with national goals has accumulated ever since they were identified as “precision poverty” targets. Kathryn Gomersall, based on her immersive fieldwork in poor cave villages on the Yellow River, concludes: “Poverty Alleviation resettlement (PAR) policy makes reference to concentrating dispersed households to improve oversight of the population. Enhanced supervision thus allows for an efficient civilising process in which the suzhi [human quality] mentality is cultivated. Households from both villages stated that there are strict rules for living in the village and people are now under close supervision of the village committee. In Yen village, households explained that neighbours govern by watching each other’s behaviour. Village committee members or friends of the village head report everything that occurs in the village back to the village head. Observance of social norms is ensuring a tight social order and social stability. The suzhi discourse emerged during interviews with households when questioned about living in the village. Behavioural norms are governed in the village through the pursuit of “human quality” or “civilised behaviour” that is acquired through the embodied experience of living in the village. One man in Tao village commented “people are more self-aware and have more self-discipline, because there are clearer norms for behaviour now that we are living in the village. The human quality has improved”. The People’s Congress Representative concurred that despite the sentimental value of the caves resettlement is a process of “social evolution.” The human capital aspects of suzhi are being indoctrinated into rural people in an attempt to devalue traditional rural livelihoods as ‘backward’ and to encourage pursuit of civilised livelihoods outside of farming.” [8]

All of these impacts are experienced by resettled Tibetans too, further up the Yellow River, for example those removed from areas flooded by the cascade of hydro dams China has built on the Ma Chu/Yellow River in Amdo, where anthropologist Jarmila Ptackova came to similar conclusions.

HOW TIBETANS EXPERIENCE RELOCATION & INTENSIFICATION

Part of the civilising agenda of the party-state is to encourage entrepreneurialism, which becomes a necessity because state subsidies cover only part of the costs of building new houses, and newly resettled villagers are in debt. This suits central planners and their civilising mission, not only because it cuts resettlement costs but because it incentivises intensified production and an attitude that prioritises wealth accumulation to service debts.

Since it is mostly men who can access entrepreneurial opportunities, this has a gendered dimension, as Gomersall notes: “a materialistic culture is eroding cultural heritage in villages. During interviews women commented that the men’s preoccupation with making money is exacerbating the gender divide with respect to participating in cultural activities. Middle aged housewives in Yen village stated that “people only care about their own self-interest and aren’t as close as before due to increased focus on making money.” One woman remembered a time when men would get together and drink wine during festivals, but this is no longer the case. “If a festival gets in the way of making money then they won’t celebrate it at all.” Despite Yen assigning the female village committee member the responsibility of organising cultural activities such as dancing and art, women only participate in these activities. By concentrating people into villages, rural identities are conditioned and favour profit centred subjectivities at the expense of alternative social and cultural functions. This process is monitored by the Party-state that can now maintain close supervision of the population to ensure stable progress towards achieving goals.

“In naturalising the dominant political economic rationale certain subjectivities are privileged while others are silenced. Undesirable classes, genders and ages that are deemed low quality and do not meaningfully serve bureaucratic order are marginalised. The suzhi discourse that privileges urban middle class consumptive lifestyles and demeans the rural classes was most powerful in Tao village. People were the poorest here and were indoctrinated with a discourse that dictates village life as a process of ‘social evolution’ and where simple-minded farmers could learn to participate in intellectual conversations about making money. The constant pressure to earn money and pay for housing and the increased cost of living is having a dislocating effect on social relations that serve alternative rural social and economic purposes. Recreational time spent together has diminished for villagers since taking on debt, which is offsetting any benefit derived from bringing people together. Women in Yen have noticed a general atomising effect since living in the village and express a strong desire for a previous time when neighbours shared meaningful social and cultural time together. The women’s resentment at the emphasis on self-interest and profit reflected their acknowledgment that PAR is having a socially and culturally dislocating affect in the village.”[9]

“Through resettlement, villagization acts as a process of subjection that achieves China’s political economic goals of poverty alleviation, urbanisation and demand driven economic growth. The micro politics of power reveals that in achieving Chinese government goals, resettlement serves to redefine space in terms of a continuum that challenges the dominant development trajectory. Therefore resettlement is critiqued as a power laden activity in which planning practices organise living environments and livelihoods and, in the process, reconfigure local identities. Poverty Alleviation Resettlement (PAR) is used to govern the behavioural norms of rural people and this includes maintaining social stability.”[10]

These are the dislocations experienced by dislocated Tibetans too. So seldom do we hear of these accelerations, the privileging of selfishness, gendered inequalities and endless bureaucratic intrusions into private life. We don’t hear because Tibetans are not free to tell their stories, and only a scatter of ethnographers get to live with the displaced long enough to gather such stories.

IMPROVING TIBETAN HUMAN QUALITY?

In the absence of plentiful thick descriptions, we can instead focus on official boasts of shipping retrained Tibetans right out of Tibet. But the spatial move doesn’t have to be far. The two relocated villages Gomersall lived with didn’t shift far, yet everything changed.

Those changes, moving villagers into a faster lane, are exactly what the party-state wants. Poverty alleviation or environmental protection are the labels attached to these governmentalities, but the agenda goes way beyond those labels.

Gomersall and many social scientists call this suzhi, a term familiar to all Chinese that is hard to reduce to English.[11] It is often translated as “human quality” or “human capital formation”. It is packed with privilege, coming from a speaking position of the mentor benevolently educating the ignorant poor in how to become modern, civilised, individual, hygienic, urban, disciplined, productive, compliant, accumulative and rich. This is a full imperial civilising mission, requiring transformation of the person, abandonment of local identity, embrace of national identity.

Inherent to suzhi is the assumption that the party-state is the acme of suzhi, the peak of civilisation, the exemplary model all must learn from. To possess suzhi is to know what is best for others, even when they fail to see it for themselves. So it is the solemn and arduous mission of the party-state to raise the level of suzhi of everyone, without exception, ignoring the false consciousness of those who would rather live on in their cave or pastoral yak hair black tent. Modernity is compulsory, because it is the destiny of all mankind, it is social evolution, it is a universal law of development, and it makes China stronger when everyone contributes to nation building.

These are extravagant claims, grounded in Marxist utopianism, Christian teleology and social Darwinist survival of the fittest, all of them European modes of thinking embraced by the CCP, that share little with Chinese tradition. Yet they prevail in China. Not only is this Eurocentric concept of destiny prevalent among the elite, it is their mission to do everything possible to get everyone to embrace the pedagogy of cultivating their suzhi.

[1] Sarah Rogers, Jie Li, Kevin Lo, Hua Guo, Cong Li, China’s rapidly evolving practice of poverty

resettlement: Moving millions to eliminate poverty, Development Policy Review, 2020;38:541–554.

[2] Ruth Rogaski, Hygienic Modernity, California, 2014

[3] Reshaad Durgahee (2017) ‘Native’ Villages, ‘Coolie’ Lines, and ‘Free’ Indian Settlements: The Geography of Indenture in Fiji, South Asian Studies, 33:1, 68-84,

[4] Fang Yunzhong, Poverty Reduction in China, China Pictorial Publishing House, Beijing, 2013, 157

[5] Poverty Reduction in China, China Pictorial Publishing House, Beijing, 2013, 27

[6] Xi Jinping, Speech at a Symposium on Resolving Prominent Problems in Poverty Alleviation, English Edition of Qiushi Journal, October-December 2019|Vol.11,No.4,Issue No.41 | http://english.qstheory.cn/2020-01/13/c_1125443359.htm

[7] Hanjie Wang, Qiran Zhao, Yunli Bai, Linxiu Zhang & Xiaohua Yu, Poverty and Subjective Poverty in Rural China, Social Indicators Research (2020) 150:219–242

[8] Kathryn Gomersall, Resettlement practice and the pathway to the urban ideal, Geoforum, 96 (2018) 51–60

[9] Gomersall, Resettlement practice and the pathway

[10] Kathryn Gomersall, Governance of resettlement compensation and the cultural fix in rural China, EPA: Economy and Space, 2021, Vol. 53(1) 150–167

[11] Ann Anagnost, The Corporeal Politics of Quality ( Suzhi ), Public Culture, Volume 16, Number 2, Spring 2004