A blog series on China’s lust for lithium from Tibet, blog 3 of 3

SAVING OUR PLANET, THROUGH MORE MINING THAN EVER

Lithium extraction by any means, at whatever financial and environmental cost, makes sense only if decarbonising a world addicted to fossil fuels is the sole goal, and nothing else matters. Getting lithium out of the ground, wherever it can be found, is a foolishly narrow goal How narrow? Just look into the whole life cycle of those lithium batteries and the cars driven by them.

A major reason the planet still struggles to face the climate crisis is narrow thinking. For so many decades the carbon pumped into the atmosphere was invisible, not on the accounts, an externality that was not part of the bottom line of any corporate emitter. Now we are at last starting to decarbonise, but again narrow thinking prevails, and again the cost of decarbonising at all costs is rising. We are fixated. If we have only a single objective, all the unintended but foreseeable consequences will intensify. One day our children will look back and ask how come we were so single-minded.

Now we are at last starting to decarbonise, but again narrow thinking prevails, and again the cost of decarbonising at all costs is rising. We are fixated. If we have only a single objective, all the unintended but foreseeable consequences will intensify. One day our children will look back and ask how come we were so single-minded.

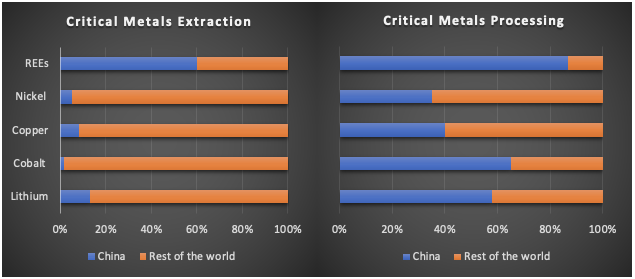

Investors are piling into lithium extraction, copper, nickel and rare earths extraction because there will be a big expansion of mining worldwide, to achieve decarbonisation. Miners are expecting a bonanza. A “clean, green” new world actually means much more mining.

For indigenous rights advocates, and environmentalists, this looks like deja vu all over again. Local communities, indigenous land guardians and environmentalists have worked for decades to show the downsides of extractivism, the pollution of lands and streams, the displacement of landholders, the despoliation of ecosystems, the damming of rivers to power remote mines, and much more.

Surely the time has come for a more inclusive approach, a set of nature-based solutions that avoid disempowering and colonising remote communities in the name of decarbonisation. Surely we can acknowledge the harm that will come, due to China’s goals of becoming as urbanised as the richest countries, as quickly as possible, of leading a new industrial revolution, of becoming as rich as the richest countries, and of increasing carbon emissions until 2030, and only then begin reducing them.

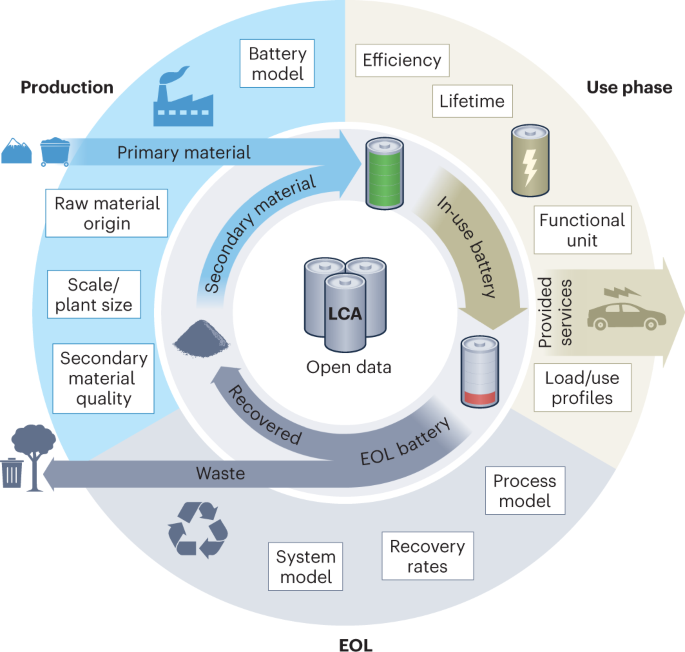

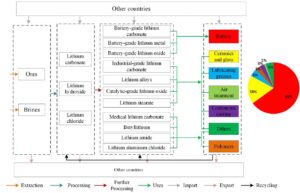

If battery powered electric cars, buses and trucks are the way ahead, we need to understand their total impact over the life cycle of those lithium batteries. Only if we take into account the social and environmental costs of extraction, mine waste dumping, processing, manufacturing, disposal and recycling of lithium batteries can we tell if this is wise, or foolishly swapping one crisis for another.

In reality the electric car industry, propelled by China’s party-state subsidies and made-in-China strategies hasn’t even worked out how to prevent battery powered cars that crash from burning.

Nor is the electric auto industry designing the cars, SUVs and trucks with recycling of lithium, nickel etc built in. Competition between China’s electric car manufacturers is so intense, the emphasis is on speed. Speedy (often robotised) production, speedy sales, speedy on road performance, speedy profits are all the industry, shareholders and the party-state want to talk about.

Nonetheless there have been attempts at life cycle assessments, published by scientists urging recyclability be a design feature, not a problem for a distant future, someone else’s responsibility.[1]

Their findings are alarming: “a 30% increase in GHG [greenhouse gas] emissions from vehicle production compared with conventional vehicles. Around 40% of total emissions are associated with electricity use, for which the GHG emissions in China are over two times higher than the level in the United States. According to our analysis, it is recommended that great efforts are needed to reduce the GHG emissions from battery production in China, with improving the production of cathodes as the essential measure.”[2]

“We found that the energy consumptions and greenhouse gas emissions of the LiB [lithium battery] materials in this study are significantly higher than that drawn from GREET [Greenhouse Gases, Regulated Emissions, and Energy Use in Transportation]. This will lead to 62 to 91% more greenhouse gas emissions from materials made in China than those in the United States in order to produce LiB cells of the same capacity.”[3]

These scientific studies also compare the impacts of the turn to rock lithium instead of salt lake lithium. Again, the results are alarming: “We compare the environmental impacts of lithium by LRT [lithium rock-based technology] with that by brine-based technology (LBT) and the Li-ion battery using lithium by the two methods. The result shows that the impacts of rock-based lithium production are dominated by the leaching process, which has the highest levels of impacts for 8 of 10 environmental categories. Besides, all 10 impact categories of lithium produced by LRT are much larger than that by LBT, with differences up to 60.4 -fold. We also find that the Li-ion battery pack by rock-based lithium offers a 17–32% increase in acidification and global warming potential relative to that by brine-based lithium.”[4]

Other studies comparing brine lithium extraction with hard rock lithium extraction reach the same conclusion: rock lithium has a much greater environmental cost.[5]

Are we going to save the planet by buying lithium battery powered cars made in China? The more closely we look, the more it seems the wheels are falling off.

UNKNOWN LITHIUM UNKNOWNS

The hot money pouring into this bubble prices the rock lithium of eastern Tibet astronomically. Yet this enthusiasm for rock lithium rather than easily extractable salt lake lithium, is very recent, so recent the deposits in Tibet are not well understood. Their extractable tonnages is far from verified, with much uncertainty about how these deposits formed, and where the elusive lenses of lithium, often deep underground, are located.

Why, especially in China and Tibet, was the move away from accessible lithium-rich salt lake-beds to lithium in the mountains of eastern Tibet; in rugged mountainscapes known until recently mainly for their extraordinary biodiversity? Why the bubble frenzy? Why, despite a dip in lithium prices in second half of 2023, is lithium extraction in China as profitable as ever?

Not only is the auctioning of mining and exploration rights staged by state agencies, the boom in lithium powered vehicles has been nurtured, subsidised and engineered by the party-state for a long time. Now the moment has arrived, when China’s electric car makers are going global, capable of competing with the most famous global brands, both on price and quality. All that is needed is guaranteed supply of the raw materials. New tech means batteries may be made without nickel, a metal China lacks onshore. But lithium is foundational. If you don’t own a lithium mine, you are not in the game, especially if your business model is vertical integration, owning it all, from the remote mine up in the mountains, to the gleaming showroom floor where you sell cars direct to the public, bypassing dealers.

“China’s largest puréed food manufacturer Nanfang Black Sesame Group said in March that a wholly owned subsidiary of the Shenzhen-listed company, would pivot its business from food to energy storage and invest Rmb3.5bn ($490mn) in building a lithium battery production base.”

For China’s party-state the stakes are high. China plans to keep growing, to urbanise almost all its citizens, including the Tibetans, to raise incomes to levels comparable to the rich club. Its path out of the classic middle income trap is to be even more the world’s factory, with China’s national champion corporations leading the world in production and sales of all technologies of a decarbonised future, even if, in the near future that means more coal fired power stations, more hydro dams, more lithium and copper mining from Tibet, more long haul trucking of semi-processed minerals from Tibet, more polluted rivers, and more distraught, displaced Tibetans.

In China’s grand plans, Tibet is more than a captive mine at the uppermost end of vertically integrated commodity chains. Tibet is also where China most intensively builds the tech it sells globally: the high speed railways, expressways, hydro dams, power grids, solar farms and wind power. Tibet is a showroom, a sales space for visiting delegations to inspect and be impressed by what is available.

Economists warn repeatedly that China right now is where Japan was in the 1980s, Korea and Taiwan a little later: starting to slow and even stall, as the infrastructure investments pumped by state spending generate diminishing returns, while a modern consumer-led economy is yet to emerge. China, for all its talk of socialism, has no intention of redistributing wealth to consumers to stimulate demand and power the endless creation of new human desires that market economies are so good at. In the absence of taxing the rich and ensuring stronger social security for the poor, China looks for other strategies to ensure growth is endless. The real estate boom is over, with 65 million uninhabited apartments sitting idle. Wealth creation must come from somewhere else. Tibet now matters to China as never before, as the source of China’s water, electricity, copper and lithium, all essential if the utopian goals of the ruling party-state are to be achieved.

The rise of Tibet to the top of China’s agenda coincides, not coincidentally, with the rise in China’s fixation on risk, and the dangers to security, which h are found wherever the security state gaze is directed. Tibet has long been classified as a security risk, often depicted as a security risk and nothing much else. Nothing new there. What is new that China’s global reach for critical minerals sourcing is now classified as a security risk. That makes Tibet, China’s back yard, more important than ever.

As risk assessment and securitisation began to engulf everything, China’s specialists in the economics of global sourcing turned to reassessing China’s global access to deposits, mines, ports and shipping routes essential to China’s dominance of critical minerals processing, purification and deployment in the world’s factory.

Lithium was high on their list, because it was a known known that China lacks sufficient lithium sources within China to meet the NEV battery boom. A major centre of investigating China’s secure sources of critical minerals is the University of Geosciences in Wuhan. As the epicentre of the Covid pandemic, Wuhan was heavily locked down, yet in 2020 economists there published an assessment. They estimated China’s lithium reserves, largely in Tibet, as 85% salt lakes, and 15% rock lithium. As early as 2016 Chinese mining companies had built small scale factories to extract, crush and process rock lithium near Lhagang (Tagong in Chinese), which functioned in summer months and idled in winter. Rukor reported on this in detail in 2017. In 2020 China was rapidly expanding its global sources of both salt lake and rock lithium, and in the final year of Trump’s US presidency, the geoscientists weren’t too worried.

They did construct a “lithium security index system”, a list of 20 demand and supply factors, evaluating each as a plus for China’s security, or a minus. There were 15 pluses, only five minuses, one of which was “net import dependence.” They listed China’s nine major corporate lithium extraction projects, only four of them in actual production, the rest were merely the securing of mining rights. Only two of the nine were rock lithium, all others were salt lakes. Of the nine deposits, only one was not in Tibet.

Their conclusion was rather relaxed: “China needs to actively integrate into the global lithium industrial chain to improve discursive power on lithium resources. We find that global coexistence is of significance for improving lithium security in China. China has increased its advantage in the global lithium industrial chain by opening up domestic markets, obtaining overseas ownership and promoting exports of downstream products.”[6]

However, they also urged China to step up domestic production: “China should strengthen the layout of the domestic lithium industry to enhance the economic security of domestic lithium resources. China should focus on improving domestic lithium security to optimize domestic resource layout and to improve the balance of supply and demand. China should, on the one hand, reinforce unified planning of the domestic lithium industry from the development of strategic emerging industries to optimize resource allocation; on the other hand, cultivate large enterprises to integrate upstream and downstream operations through the use of supporting policies in taxations, subsidies and loans.”

Then it became clear that in the US, both Republicans and Democrats urged stronger constraints on China, and the mood changed. The party-state did reinforce unified planning of the domestic lithium industry, deploying its developmentalist power to allocate incentives and subsidies to intensify exploitation of lithium from Tibet, both from salt lakes and rock lithium.

Since 2020, sourcing lithium domestically has become an urgent need, high on the agenda of securitising everything, whether justified economically or not. Yet again, Tibet is the answer to China’s problems and anxieties.

By 2023, researchers from the same Wuhan School of Economics and Management, China University of Geosciences were quite alarmed, not only due to supply struggling to keep up with demand, but because speculators, betting fast money, had taken over, inducing dramatic lithium price fluctuations, endangering security.[7]

This heightened volatility worries the security state, yet it was predictable. By 2023 China had cracked down on other industries that attract speculators, such as crypto currency mining, and much of that money had moved on to lithium.

OFFSTAGE, ONSTAGE

Chinese investors enthusiastically piling in capital to exploit Tibet’s rock lithium seldom bother to note the actual location of the mines. Tibet is just a remote “geography”, a bit inconveniently far from where the battery action is, but that’s solvable by the tech guys. All that matters is that the mines belongs to China and can’t be interdicted. As cashed up investors pile out of crypto and into Tibet rock lithium, it all looks good.

Tibet is a cipher, voiceless and silent, in this latest rush to riches. Not for Tibet can there be any consideration of whether there should be extraction, or whether extraction could finance much needed development, for example the rebuilding of local community schools China closed over the past decade to concentrate children in boarding schools, breaking families apart.

Swarming into the new rock lithium extraction zone of eastern Tibet are unlikely entrants, such as: “Inner Mongolia Dazhong Mining Co., Ltd. engages in the iron ore mining and dressing, iron concentrate and pellet production and sales, and processing and sales of machine-made sand and gravel. Its business scope includes mining, processing and sales of mineral products; mineral smelting; processing and sales of oxidized pellets; road operation and management; general cargo road transportation; mineral products iron ore, steel, building materials, construction machinery, heavy vehicles, mining equipment, mechanical and electrical products purchase and sale; and sand and gravel processing and sales.”

This iron ore miner based in distant Inner Mongolia was top bidder for the Jiada deposit, offering RMB 4.2 billion, $580 million , resulting in a brief share price spike, only briefly interrupting its gradual decline.[8] What Dazhong gets for that price is only ongoing exploration rights, that may confirm the rubbery estimate of the Sichuan authorities that the orebody is anywhere between 29.7 million tons and 47.2 m tons, within which the actual lithium content is merely 1.26%. If Dazhong can drill lots of expensive deep holes and prove a more reliable tonnage, within its five year exploration right, it may then be able to onselll to a miner capable of extraction. Or the bubble may have collapsed. By October 2023 the bubble is deflating, but Dazhong is doing its patriotic duty, central leaders will be pleased.

Wall Street Journal: “China’s Ministry of Natural Resources said earlier this year that it would boost efforts to identify and develop domestic reserves of minerals such as lithium. To do so, it pledged to encourage investment in mining exploration and to give priority to land use for extracting strategic minerals. China is home to only 7% of the world’s known lithium resources, of which less than one-third can currently be mined in a commercially viable manner, according to the U.S. Geological Survey of 2023. That is because China’s lithium, which is either contained in salt lakes or in one of two types of hard rock known as spodumene and lepidolite, is often scattered in different places and of inferior quality. Lithium is difficult to extract from salt lakes because of their high levels of impurities, while spodumene is most common in remote high-altitude regions.”[9]

Fastmarkets.com, advising investors worldwide, persists in predicting lithium prices, like oil prices, will remain high over the long term. Vicky Zhao, Fastmarkets’ senior analyst of battery raw materials, says “Chinese lithium producers tend to look more for domestic lithium supply rather than from the international market to reduce risks associated with geopolitical uncertainties.”[10]

In Tibet there is no possibility of anything like the Africa Mining Vision, which proposes a dignified future of selective mining and value adding that enables the poor to develop. The profitability of lithium extraction may be as great a windfall as today’s petrostate bonanza, yet the officially designated Tibetan autonomous prefectures where the rock lithium is found, have no say. Tibet has no opportunity to finance its development, as Indonesia does, by insisting on local processing of battery materials.

CAPTIVE MINING IN A CAPTIVE COLONY

Silencing Tibetan voices, refusing them any voice in the public sphere, any exercise of legal rights, is enforced by the ubiquitous cameras, surveillance monitoring devices, big data torrents fed into the Lhasa big data hub, where patterns of anything at all deviant are tracked by AI algorithms. Many of these technologies are powered by lithium batteries. Not only are Tibetans disempowered, they are disempowered by the predatory extraction of their own mineral endowment.

China proclaims unswerving commitment to clean, green new energy, yet also persists in building more and more coal-fired power stations. China proclaims itself leader of the G7 since China has officially achieved prosperity; yet at the same time the natural leader of the Global South. China says it is, and will remain , both developed and developing. China walks both sides of the street. Plundering lithium from Tibet to power China’s zoom zoom electric car market worldwide, is not going to save this planet.

- [1] Yang Yang, Libo Lan et al., Life Cycle Prediction Assessment of Battery Electrical Vehicles with Special Focus on Different Lithium-Ion Power Batteries in China, Energies, 2022, 15, 5321. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15155321

- Tao Feng et al., Life cycle assessment of lithium nickel cobalt manganese oxide batteries and lithium iron phosphate batteries for electric vehicles in China, Journal of Energy Storage 52 (2022) 104767

- Quanwei Chen et al. Investigating carbon footprint and carbon reduction potential using a cradle-to-cradle LCA approach on lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles in China, Journal of Cleaner Production 369 (2022) 133342

- Xin Lai et al., Investigating greenhouse gas emissions and environmental impacts from the production of lithium-ion batteries in China, Journal of Cleaner Production 372 (2022) 133756

- Yixuan Wang et al., From the Perspective of Battery Production: Energy–Environment–Economy (3E) Analysis of Lithium-Ion Batteries in China, Sustainability, 2019, 11, 6941; doi:10.3390/su11246941

- Qiang Dai , Jarod C. Kelly , Linda Gaines and Michael Wang, Life Cycle Analysis of Lithium-Ion Batteries for Automotive Applications, Batteries 2019, 5, 48; doi:10.3390/batteries5020048

- Mudit Chordia, Taking stock of large-scale lithium-ion battery production using life cycle assessment, dissertation, Chalmers University of Technology, Goteborg, Sweden 2022

[2] Han Hao et al, GHG Emissions from the Production of Lithium-Ion Batteries for Electric Vehicles in China, Sustainability 2017, 9, 504; doi:10.3390/su9040504

[3] Renshu Yin, Shuhan Hu, Yang Yang, Life cycle inventories of the commonly used materials for lithium-ion batteries in China, Journal of Cleaner Production 227 (2019) 960e971

[4] Songyan Jiang et al., Environmental impacts of lithium production showing the importance of primary data of upstream process in life-cycle assessment, Journal of Environmental Management 262 (2020) 110253

[5] Jarod C. Kelly, Michael Wang, Qiang Dai, Olumide Winjobi, Energy, greenhouse gas, and water life cycle analysis of lithium carbonate and lithium hydroxide monohydrate from brine and ore resources and their use in lithium ion battery cathodes and lithium ion batteries , Resources, Conservation & Recycling 174 (2021) 105762

[6] Na Zhou, Qiaosheng Wu,, Xiangping Hu et al., Synthesized indicator for evaluating security of strategic minerals in China: A case study of lithium, Resources Policy, Nov 2020,

[7] Yangyan Shi, Yu Feng, Qi Zhang, et al., Does China’s new energy vehicles supply chain stock market have risk spillovers? Evidence from raw material price effect on lithium batteries, Energy 262 (2023) 125420

[8] Platts Metals Daily, 14 August 2023

[9] Sha Hua, Chinese Firms Scramble to Secure Lithium — Companies race to develop domestic mines to cut reliance on overseas sources, Wall Street Journal 18 August 2023

[10] Zihao Li , Fierce competition to secure lithium feedstock supply in China signals long-term optimism, FastMarkets AMM, 15 August 2023