Blog three of five on an industry totally new to Tibet: mass manufacture of millions of alien trout in hydro dams on the Ma Chu/Yellow River

URBAN DEMAND, URBAN CONFUSION

While trout production in Tibet has taken off, there has been much trouble at the far end of the commodity chain, among wealthy urban consumers in Shanghai and other cities. The trouble is over whether the fish from Tibet are trout or salmon, which is more prestigious, since salmon is better known as an expensive imported fish, capable of enhancing the reputation (and human quality, suzhi) of he who stages a banquet featuring such a luxury.

The agitation by consumers keen to performatively display their sophisticated tastes peaked in 2018, with demands that salmon, Salmo salar, and trout Oncorhynchus mykiss be separately labelled, otherwise ostentatious displays of wealth, featuring imported salmon, will be haunted by accusations of using cheaper Tibetan fish. It culminated in a showdown three hour session in Shanghai, with scientists and lawyers for consumers demanding labelling separating the two alien species, while the trade association tried to fudge the difference. This was reported in detail by major media. CCTV even did a mini investigative 11 minutes doco, with footage taken by drone flying over the Tibetan trout cages.

This consumer revolt comes just as state capitalism in Tibetan man-made lakes was at last gathering momentum. As elsewhere in China, the distinction between private enterprise and the all-powerful party-state is blurry. The key operator is 青海民泽龙羊峡生态水殖有限公司 the Qinghai Minze Longyangxia Ecological Aquaculture Co. Ltd., which has much official support.

There is inevitably a Qinghai province “Implementation Plan for Accelerating the Green and Organic Development of Fishery Farming” which regulates the impounded waters, a public good created by state investment in damming, promising to protect the rights of operators and subcontractors, while also defining which areas can be farmed, and which are off-limits. These regulations give maximum rent extraction opportunities to officials, in exchange for official permissions. Privatising public goods privatises rents. The existence of a published regulatory regime also assures consumers the fish protein they eat is certified organic and clean, justifying a high price. Another win-win, except for the fish.

Part of the marketing pitch for the rainbow trout-cum-salmon produced in Tibetan dam reservoirs is that the slaughtered, gutted, packed and chilled fish are then rushed to Xining airport for fast delivery to coastal consumers. By road Xining is no more than two hours away.

China’s appetite for salmon has been influenced by Japanese tastes, which means eating fishmeat raw. This is a further driver of consumer insistence that supply must be clean and disease free. The regulatory regime governing production is meant to assure consumers the entire supply chain is clean and green.

In reality, it’s a bit more complicated. Industrial aquaculture relies on feeding pellets of manufactured formulated dry food to the growing fish, some of which may not be eaten, thus adding to the nutrient level of the lake. Growing fish excrete wastes, which further add to nutrient levels. Further, preventing pandemics among fish penned closely together inside cages usually means adding antibiotics to their feed. The slaughter, scale removal and gutting of farmed fish adds more wastes to be disposed of, or fed back to the remaining fish, part of the pelletised prefabricated fish food.

The scaling up of rainbow trout production in Tibetan dam lakes is so recent, there seems as yet little evidence of nutrient pollution.[1] Extra nutrients would foster phytoplankton and algae blooms, which can and do occur in fish farm lakes around the world. The dam lakes are considered oligotrophic, which means they are rich in oxygen but poor in nutrients. If, however, plans for further intensification of trout sold as salmon are realised, production will rise much more, far beyond the 15,000 tons of fish a year now. Officially, there is a ceiling of 30,000 tons production limit,[2] but premium consumer price payments make greater production a great temptation.

GLOBALISED SALMON & TROUT TRAFFIC GLOBALISES TIBET

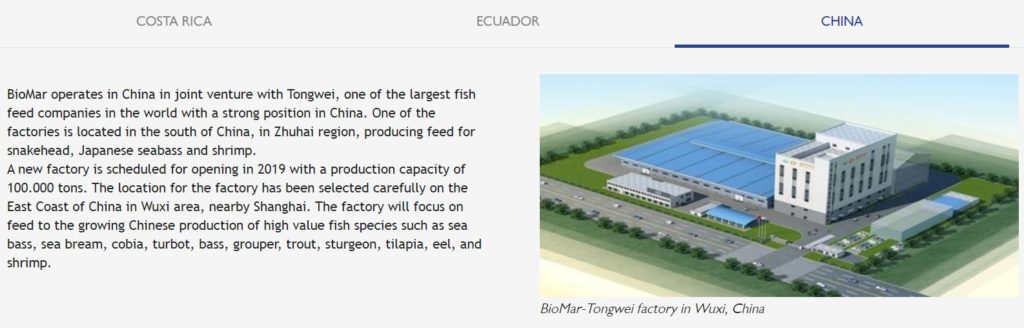

Tibet is now globalised, integrated into the global flows of fish eggs, fish feed and slaughtered fish competing for top price in Shanghai supermarkets.

Tibetans were never asked if this was the path to development and future prosperity. China takes it for granted that the implantation of a trout farming industry in the artificial lakes behind China’s ma Chu chain of dams in Amdo is by definition beneficial to Tibet.

Not only is Tibet thus globalised, without any debate or discussion, this global trafficking in fish enmeshes Tibet in the global politics of luxury consumption. China chose to punish Norway for awarding Nobel Prizes to dissident Chinese, by slashing imports of Norwegian salmon. Once that punishment ran its course, the traffic returned to normal, so much so that refrigerated Norwegian salmon are airfreighted to China, with the planes returning empty. That adds to climate heating emissions across Eurasia.

Whether Norway is punished or rewarded by China now impacts on Tibet, causing spikes and slumps in demand, making Tibetan fish farms more or less valuable. Tibet is thus caught up in the multiple ethical dilemmas of intensive industrial aquaculture, without having any say at all.

FISHY ETHICS

There are ethical issues about introducing alien species on a river which, upstream, in the huge Sanjiangyuan (Three river source) National Park is dedicated above all to protecting native Tibetan biodiversity. Introducing triploid trout which cannot interbreed with native Tibetan fish reduces risks, but alien species can be highly invasive, if they escape their immersion in steel cages. For native fish this is a double challenge, since they cannot get over concrete dam walls to continue their migrations up and down river, especially when there is a cascade of nine hydro dams on a short span of river. A cascade of interruptions.

There are ethical issues on the feeding of antibiotics to the impounded trout in their cages, which has been done routinely, not only to control diseases among fish packed tightly but also because laboratory research suggests trout fed erythromycin or other antibiotic medicines grow faster, which means more profit. This has been highly controversial, at a time when bacteria are developing resistance to antibiotics, and the world is running out of antibiotics that are effective against human infections.

Further, the trout bred in Tibetan reservoirs have a pale flesh, not the orange-red that consumers expect of trout, even more of salmon, which the Qinghai industry hopes to mix up in consumer minds.

The solution is to feed astaxanthin to the growing trout, as a further feed additive. Astaxanthin can be extracted from algae and yeasts, but also from salmon and other seafood species. [3] In Tibetan eyes, this may be similar to being required to eat your mother.

Ethical issues surround the impact on water quality in the dams and below, of penning millions of fish in cages. The fish consume the oxygen dissolved in the water, and release their wastes into the water. Feed pellets that are not snapped up by hungry fish sink into the water, providing nutrients for much else to grow, far beyond their natural occurrence. The balance of nature is upset.

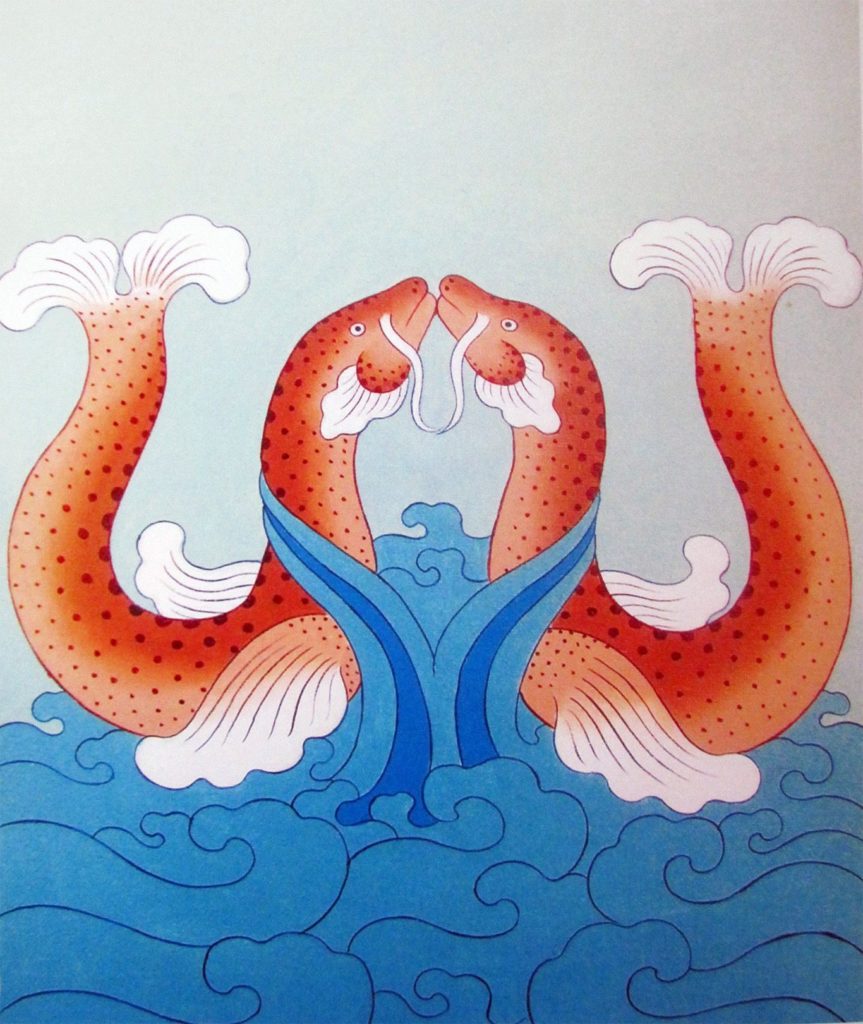

For Tibetans, industrial fish production is in itself an ethical issue, at a time when a revitalised vegetarian movement, expounded by popular Buddhist teachers, attracts many Tibetans, who are reminded by their religious guides that Chinese like to buy fish live, and drop them alive into boiling water. This horror has deep roots in Tibetan culture. In 1370 Dorje Lingpa spontaneously sang a song of sadness at the karmic consequences for fishermen, in what today is Bhutan, whose lives were given over to catching and killing so many sentient beings.[4] His song is part of a widely known and popular tradition of songs remonstrating with local communities over wasting this precious life on fleeting satisfactions. Songs sung in contemporary Tibet celebrate community sociability with metaphors of golden fish:

“The beginning of my song/is nine floors of a golden/building in a walled city.

The sun rises naturally on a/golden nine-floor building.

The middle of my song is/a sprout of branches.

Cuckoos naturally fly around/sprouting branches.

The end of my song is a rising/lake. Golden fish naturally/swim around in a rising lake.”[5]

The golden fish, gser nya in Tibetan, are one of the eight auspicious symbols found repeatedly in Buddhist imagery, signifying fortune and fearlessness. Tibetan ethnographer Kabzung (Ga’errang in pinyin Chinese) says: “During my fieldwork, many Tibetans told me that certain types of living beings are associated with much greater evil deeds than others; for instance, fish is one such sinful food.”[6] The embedded Tibetan custom of tsethar, of ritually freeing animals destined for slaughter to live out their lives undisturbed, has been extended to fish, which Tibetans buy live in Chinese wet markets, to release them back into rivers.

SCALING UP

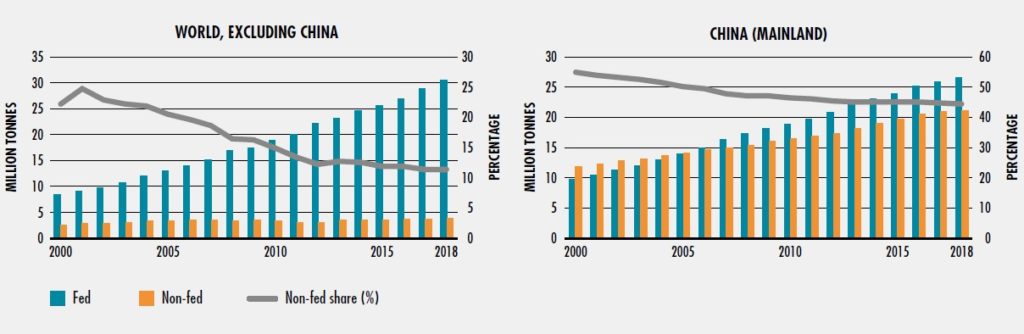

Yet are we making a big deal out of a small industry? The trout cages on the Ma Chu in Amdo currently produce only 15,000 tons of fish a year. Compared to global production and consumption of trout, that’s not a lot. Compared to global factory farming of salmon, it’s even less, even if the farmed trout never get bigger than four kilos, so 15,000 tons is four to five million fish a year.

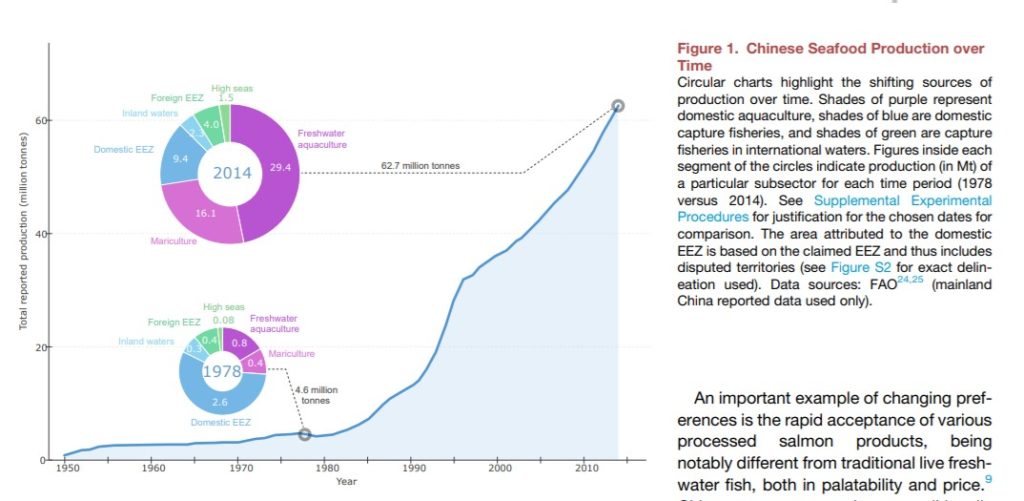

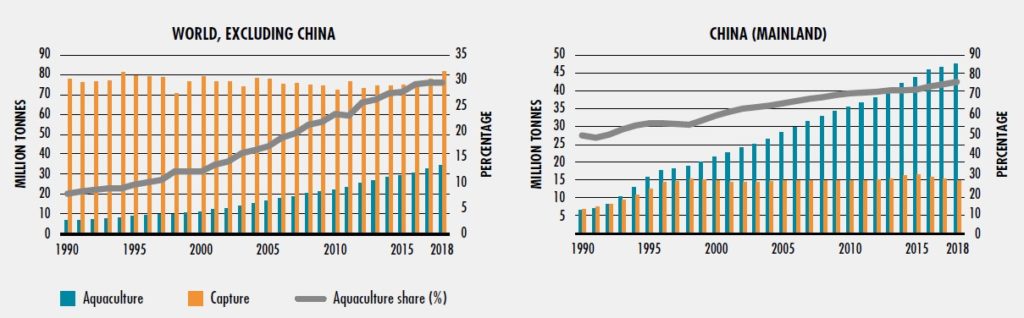

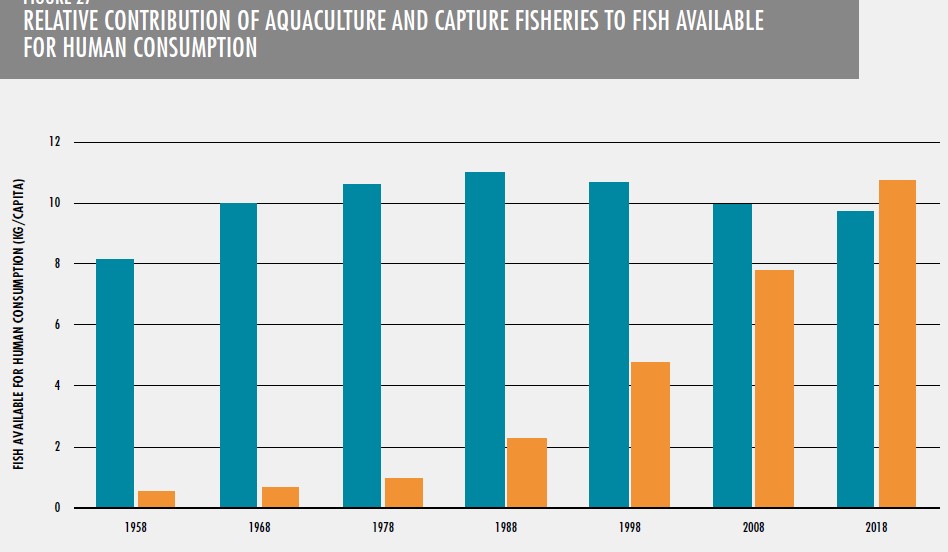

In the wider context, China is by far the world’s biggest producer of aquaculture fish, both from inland and coastal waters; as well as sending its fishing fleets worldwide to capture fish in international waters, process them in China, then export. In every aspect of fish and seafood production, China is a giant, its predatory fishing fleets much resented by developing countries ill equipped to defend their waters.

“China, the world’s largest fishing nation, has a distant water fishing fleet estimated between 4,000 to 17,000 vessels (compared to 300 for the United States). This fleet accounts for 15% of the global fish catch and 40% of global fishing effort. China’s fleet fishes in the sovereign waters of more than 50 countries.”

According to the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation, China’s aquaculture production is edging close to 50 million tons a year (inland and coastal).

However in Tibet, this is an industry that is young, just beginning to scale up. Even though Chinese and United Nations fish experts have been trying to mass manufacture fish in Tibetan reservoirs for three decades or more, only now has production taken off. This is an industry that could intensify and accelerate greatly; that’s the plan.

What has held back production is decades of failure, despite the best efforts of the UN Food & Agriculture Organisation, which remains an enthusiastic promoter of aquaculture. UNFAO initially suggested salmon would be suitable, but one disaster after another followed.

Now Wang Guojie, deputy director of the Qinghai Fishery Environmental Monitoring Station, has a 2020 long list of ongoing problems in those Ma Chu dams, and ambitions, if this industry is to achieve its wealth accumulation goals:

“There are currently at least five problems restricting the expansion of our industrialization scale: First, the control of cage culture capacity has not been strictly implemented. Since Gongboxia Reservoir, Suzhi Reservoir, and Lijiaxia Reservoir are jointly managed by two or three counties, although there are reservoir breeding capacity quotas, the reservoirs are not subdivided by counties, and the lack of specific and effective strict control measures has caused some poorly implemented regional breeding capacity control.

“Second, the implementation of relevant systems for biosafety management is not strict. Some farms have inadequate implementation of biological safety management system measures such as vehicles, non-standard disinfection of personnel, lack of treatment facilities for diseased and dead fish, etc.; some farms are backward in fish disease diagnosis and epidemic prevention and control technologies and methods, and the risk of epidemic diseases still exists ; Individual farms are self-propagating and self-breeding, and lack of relevant quarantine procedures for reporting and filing, which not only brings a great epidemic risk to the salmon trout cage culture industry in Qinghai Province, but also poses a potential threat to the ecological safety of wild fish in the Yellow River.

“The third is to improve the production and supply of improved varieties. At present, there are three salmon trout breeding farms in Qinghai Province, which supply aquaculture production. The supply of refined species is totally dependent on foreign imports and there is no own breeding technology, which has become the bottleneck of the development of the salmon trout industry in our province.

“Fourth, brand building is not strong enough. Although the trout culture environment of salmon trout in Qinghai Province is excellent, the farming mode and facilities are advanced, and the product quality is good, due to the large number of existing farm brands, the product quality is uneven, no regional common brand has been formed, and the brand awareness is not high. The premium potential of the common brand has not yet been realized, affecting product sales and breeding efficiency.

“Fifth, the service capacity of county-level aquatic stations needs to be improved, and there is a shortage of aquaculture professionals. Judging from the basic disaster situation in the past two years, the cages in some county farms are unreasonably set up, and the cages have been damaged due to floods and the cages have been stranded. Facilities such as quality testing cannot meet the needs of large-scale farming for aquatic product quality testing, water environment monitoring, and epidemic prevention and control, which has affected the effective development of grass-roots fishery science and technology public services.”

This long list of the problems of industrial intensification suggests, as is usual in China, that the party-state will step in, order intensification by decree, step up its subsidies, concessional finance, tax breaks and other incentives to ensure the industry succeeds.

In a time of accelerating intensification, Wang Guojie’s complaints signal the likelihood the Qinghai provincial party-state will step in and impose controls, plans and targets, effectively nationalising this new asset class, the waters of the man-made reservoirs behind the dam walls, to ensure not only greater profitability, but that the wealth capture opportunities go to well-connected urban cadres. This is standard. Wang Guojie’s case for intensification is the sole full-page feature story in the 2 June 2020 edition of the Qinghai Scitech News, a sure sign the developmentalist state, keen to further industrialise Amdo/Qinghai will step in.

With finance provided by the state owned policy banks, which must obey the party-state, many more trout cages could be built, on all the Amdo Ma Chu dams, connected to fully industrialised slaughter gutting, packing, chilling and air freight shipping to distant markets: a full cold commodity chain. Intensification means a capital-intensive industry, reliant on technology and standardised production protocols, employing few humans in a largely automated production line. Jobs for Tibetans -should they want such work- will be few.

The potential for upscaling is huge. The industry has managed to blur the distinction in consumer minds between trout and salmon, raising the tantalising prospect of joining the premium priced market for imported salmon, flown in from Norway.

How many trout could be produced in the 300 kms of cold, clear water of the nine hydro dams China has built on the Ma Chu in Amdo? The current 4 to 5 million fish a year could possibly be increased tenfold. This could be the start of something big, which in turn could become a model for similar cold commodity chains for sheep, goat and yak meat from Tibetan areas, a goal the party-state has planned for decades with only limited success so far. Once a fishmeat commodity cold chain exists, expanding it to process a range of meats is not so hard.

A feature of industrial agribusiness worldwide is that power is concentrated in the hands of the processors, distributors, marketers and retailers, not the producers. Power means the ability to capture the profits, while the actual producers get to take all the risks. This is a further reason why, apart from the ethical problems from a Tibetan perspective, this is an industry with very little potential for Tibetan participation, except as unskilled low paid workers.

Nonetheless, if the party-state gets behind the push to make Qinghai fish a brand attracting premium prices, it will be presented as a further success of development and poverty alleviation, yet another win-win.

[1] Shiyu Miao et al., Long‑term and longitudinal nutrient stoichiometry changes in oligotrophic cascade reservoirs with trout cage aquaculture, Scientific Reports, (2020) 10:13483 | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-68866-7

[2] Shiyu Miao 2020

[3] Roche F. Astaxanthin As a Pigmenter in Salmon Feed, Colour Additive Petition 7C02 1 1, United States Food and Drug Administration. Hoffman-La Roche Ltd.; Basel, Switzerland: 1987. Astaxanthin: Human food safety summary; p. 43

[4] Samten Karmay, Arrow and the Spindle: Studies in history, myths, rituals and beliefs in Tibet, vol 2, 2005, Mandala Book Point, 123

[5] Wendolyn Craun, Nomadic Amdo Tibetan Glu Folk Songs Within The Settings Of Tibetan Culture, History, Theory, And Current Usage, dissertation, Bethel University, 2011, 192

[6] Kabzung, Tibetan identity and Tibetan Buddhism in transregional connection : the contemporary vegetarian movement in pastoral areas of Tibet (China), Etudes mongoles, siberiennes, centrasiatiques et tibetaines, 47, 2016