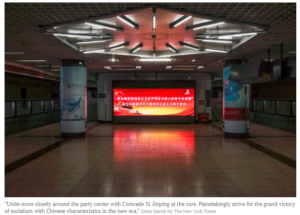

CHINA’S NEW GRAND NARRATIVE

Blog #2 of 2 on China’s new ideology for a new era

Unfashionably, we need to take ideology seriously.

These days, we seldom consider ideology, beyond sketching a thumbnail of the belief system of the enemy, only to prove how crazy bad Trumpism, or Islamic fundamentalism are, so we can rest securely in our own unexamined package of beliefs.

Does ideology matter in China? There has for decades been every reason to declare China’s explicitly Marxist ideology an anachronism that died in 1990, if not earlier, yet the Party still needs Marxian camo no-one believes in, including its authors, for product differentiation. After all, the bottom line is China wants to do business, we want to do business, and ideology is irrelevant.

The few old-fashioned analysts who parse the slogans and mnemonics that package China’s ideology tell us more about where China is heading, than the wishful thinkers in the chambers of commerce who want to see China only as a source of mutual enrichment, a bastion of rules-based globalisation and a good global citizen on the rise, that is now committed to saving the world from carbon emissions.

Tibetans know China’s ideology matters, because it is the ideology that blinds central leaders, hemming them in with top-level packaged generalisations that obscure any possibility of recognising and appreciating difference.

Tibetans need to know in advance what China has in mind, what obstacles persist in clouding recognition of common humanity, what plans and budgeted commitments follow from adhering to the ideology. Not only does China’s ideology obscure actual Tibetan lives and aspirations from view, it dictates what interventions China must make to realise its dream of a unitary, powerful, modern nation-state in which all citizens identify as belonging to the one (newly invented) race of Zhonghua minzu, the Chinese race.

To say that China is ruled by ideology is in no way to say this is a simple totalitarianism, wherein one man commands and all others salute and obey. To take ideology seriously does not require determinism, or dialectical materialism, or the trap of fascination with China as master strategist innumerable moves ahead of everyone else. This does not mean ideology in China is mechanistic or inexorable, or that the relationship between top-level design and local implementation is anything other than messy, complex, contradictory and often absurd.

In a country as vast as China, even under a highly centralised authoritarian regime mastered by one man, there are still plenty of slips, as the system led by that Thought is gamed, deflected, captured and skewed down the line of command. In the many steps between China’s mandatory Xi Jinping Thought and local exercise of state power are many contestations, distortions capture, skews and deflections. Vested interests, lower level officials, and rentier cadres mouth the official slogans as required and get on with accumulating wealth for themselves.

For decades, in the Deng era of reform and opening up, the old metaphor of crossing the murky waters of the river by feeling with the naked foot for the next stone, and the next, was a trope China was comfortable with. It almost became an antidote to the delusions of central planning, an open embrace of making it up at each step, doing whatever it takes to get to the other shore. Interestingly, in the new ideology for the officially declared new era, the metaphor of feeling for the next stone is officially repudiated, no longer befitting a great power on the march. In reality, many economists say, feeling for the next stone is exactly how China came to be so successful. For Tibetans, used to living with uncertainty, feeling for the next stone is the way to live life authentically.

Ideology, any belief system packaged into an –ism, has always, to English speakers, had somewhat negative connotations, as if it is only they who have ideologies, not we. We of course are the pragmatists, the realists, the authors of the global rules-based system that inexplicably concentrates unimaginable wealth in so few hands.

Tibetans see us all as victims of our own meta-level ideas, when they harden into ideologies, be they tacit or overt. Tibetan culture critiques all ideologies, all accreted mental habits that shortcut reality and edit experience so quickly and routinely we fail to notice what has been edited out.

Tibetans may be as prone to the seductions of ideology as any other humans, but the culture undercuts the claims of ideology as master narrative, as the transhistorical uniting of past and future that validates the present as a track towards attaining the ideal, which is always just over the horizon.

Although many philosophers such as Lyotard declared master narratives dead, although the totalising ideologies of high Stalinism and Nazism are long gone, although the Soviet collapse supposedly heralded “the end of history”, ideology is still with us. While few would credit Putin’s Russia or Trump’s America with a coherent ideology beyond a nostalgic yearning to return to past superpower greatness, China is a different story.

China’s mandatory ideology, studied and reproduced endlessly in all institutions now “surnamed Party”, in universities, media, the military and in corporations, insists it is a system of systems, an objective, logical distillation of all empirical knowledge on how to forge time’s arrow ever ahead, so China can attain utopia.

A core contention of the latest ideology is that China has now entered a new era. The goals of the previous era are now redundant, even though it is far from clear to anyone whether those goals were achieved. The rules have shifted. A new era is defined by a new dialectic, a problematic imposed from above which in turn defines China’s mission, from now to well beyond the foreseeable future, officially to 2050.

This matters worldwide because grand ideologies seldom last, but do much damage while they dominate, and curtail what is possible or even imaginable. It matters especially to the Tibetans, who see how the dominant ideology obscures them, excludes, relegates, disempowers and marginalises them, while at the same time awarding a major role to territorialised but depopulated Tibetan landscapes in the fulfilment of China’s new era ideology.

China’s new era ideology positions Tibetans only as delinquent, recalcitrant, stubbornly and irrationally denying the manifest benefits of merging into the Chinese race (Zhonghua minzu). At best, the Tibetans are peripheral, a minor nuisance; at worst, an existential threat to the unitary state of common purpose, common identity and destiny. This is not new, but new era ideology is more insistent than the ideology it supersedes that a single identity, in which every citizen is loyal to the Chinese race and its incarnation, the Party, is essential to realising “the great rejuvenation”.

The Tibetans are long used to being written out of imperial court histories, or relegated in court annals to subservient tributary roles. So the Tibetans have their own subtly but thoroughly subversive response, analysing and deflating not only official ideologies but also the packaged habits of thought we all live by, usually subconsciously. The Tibetan critique applies universally, as we all have accreted habits of mind that impose interpretations onto whatever arises, so fast we don’t notice. Both the Tibetans and the official new era ideology claim to be universally applicable, at individual and social levels. In a time when staking out an individual identity seems more than ever to be what life is about, this has relevance, not only to Tibetans but anyone who finds themselves repeating the same mistakes.

It has relevance also in a world where we are now, according to the 2018 US National Defense Strategy, back in the pre-1990 era of superpower competition. We are back in the 1980s or earlier, back to a binary world of right and wrong, but this time without the Cold War master narrative of communism versus capitalism.

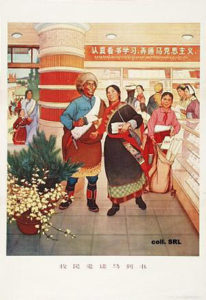

Again, the exception is China. The new era ideology manages to be both communist and capitalist, to position China as the exemplar for all developing countries, the model globalist bringing prosperity worldwide, while insisting (in one keynote speech 67 times) on everything being accomplished “with Chinese characteristics.” This may not seem a coherent ideology to nonChinese, or anything worth taking seriously, yet it is taken very seriously in China, as internally coherent, and a masterly Thought of penetrating insight into the nature of our times. It justifies rigid centralised control of all aspects of life, punishing and rewarding bad and good behaviours from jaywalking to entrenched corruption. It governs not only how nonChinese minorities are treated, but also how they are gazed upon by the eye of the party-state. The Tibetans are percepts, not perceivers, seen but not heard. It would seem China’s new era ideology has no rejoinder, no critique, no response beyond those required to salute.

Yet the CCP and the Tibetan lamas both seek human happiness for all, and both have prescriptions for how it is best attained. Both claim universal relevance. The new era ideology is a shift from economic development as the sole goal, to a much wider definition of the Party’s central role in authoring the happiness of all Chinese citizens, even when it requires uprooting them for their own good. It is possible to take the teachings of the lamas, past and present, and set them alongside the new era ideology as partners in unacknowledged dialogue, a dialogue heard clearly by millions of Han now turning to Tibetan Buddhism for a meaningful life, yet utterly invisible to everyone else, not only the central leaders but also the global community and even Tibetans in exile, who all fail to watch this subtle long game as it unfolds.

Yet the CCP and the Tibetan lamas both seek human happiness for all, and both have prescriptions for how it is best attained. Both claim universal relevance. The new era ideology is a shift from economic development as the sole goal, to a much wider definition of the Party’s central role in authoring the happiness of all Chinese citizens, even when it requires uprooting them for their own good. It is possible to take the teachings of the lamas, past and present, and set them alongside the new era ideology as partners in unacknowledged dialogue, a dialogue heard clearly by millions of Han now turning to Tibetan Buddhism for a meaningful life, yet utterly invisible to everyone else, not only the central leaders but also the global community and even Tibetans in exile, who all fail to watch this subtle long game as it unfolds.

The CCP is in no doubt that it is in a competition with the lamas for the hearts and minds of the Tibetans, a competition that is hard to win because it is so diffuse, addressed to all human minds, of any culture, to anyone who experiences confusion, anxiety, conflicting emotions.

The party-state response to a competition is cannot comprehend is to securitise, segment and separate into exclusive categories those drawn to the existential insights of the lamas. The actual regulations imposed on the Larung Gar Five Sciences Academy, in Kham Serthar, after its 2017 second destruction, give highest priority to separating the nuns and monks, overwhelmingly Tibetan, from the lay practitioners, many of whom are Han Chinese. This is standard grid management, the administrative immobilisation of populations, as practiced throughout Tibet and Xinjiang, atomising the minority ethnicity nation into discrete, tightly bounded fractions, under the constant supervision of cell managers aided by the latest surveillance technologies.

Educated urban Chinese in search of a meaningful life beyond consumption venture to Tibet to listen to the lamas, and test in their lived experience the Tibetan methods of mental transformation. The party-state worries about loss of loyalty and identification with the party-state.

The response, as it has been for decades, is to intensify the coercive demolitions, expulsions and regulatory regime dictating who may associate with whom. The official order of August 2017 makes it clear separation of students from their teachers, avoiding cross-infection of minds, is the whole purpose:

“A Simplified Program for the Separation of the Institute and Monastery at Larung Monastery Five Sciences Buddhist Institute. One: Why separate the Monastery and the Institute? [1.] The separation project is in line with the Central Government’s rule-by-law and administer-monasteries-by-law policies, and is the wish of the Central and Provincial Party Committees. 2. The separation project is being undertaken for the long-term development of both, for a proper study environment for monastics, and for the interests of both the Monastery and monastic students. The project of separating the Institute and the Monastery is to [enable] the Monastery to conduct its primary function of religious activities and the Institute to conduct its primary function of education, without overlap, the Monastery propagating Buddhist religion and the Institute promoting a serene learning environment.”[1]

This separation is further elaborated in a blizzard of regulations: “the Serta Institute Management Regulations and Organizational Agencies”, “the Serta Institute Study Regulations”, “the Serta Institute’s Institute Committee Work Provisional Regulations”, “the Serta Institute Teaching Principles”, “the Serta Institute Textbook Organization Plan”, “Regulations Concerning Religion Work.”

The official decree, signed by all departments assigned administrative control, goes to great lengths to specify the minutiae of separation, including “separation of activity centres, separate establishment of related offices, separation of organization, management and financial management, pushing forward the work of the four separations of personnel, jurisdiction, functions and management between the Five Sciences Buddhist Institute and Larung Monastery, making the Institute a standardized, law-abiding and modern Buddhist institute.” Not only will party-state authorities certify compliance, they wield direct administrative power to implement these many separations, with standard-setting and measurement of outcomes solely in the hands of the party-state, which becomes the arbiter of what constitutes a good Buddhist academy.

The official decree, signed by all departments assigned administrative control, goes to great lengths to specify the minutiae of separation, including “separation of activity centres, separate establishment of related offices, separation of organization, management and financial management, pushing forward the work of the four separations of personnel, jurisdiction, functions and management between the Five Sciences Buddhist Institute and Larung Monastery, making the Institute a standardized, law-abiding and modern Buddhist institute.” Not only will party-state authorities certify compliance, they wield direct administrative power to implement these many separations, with standard-setting and measurement of outcomes solely in the hands of the party-state, which becomes the arbiter of what constitutes a good Buddhist academy.

Since compliance must be measured and certified, Buddhist practice is reduced to what is testable: reproducible knowledge of Buddhism as doctrine. Buddhist practices of inner transformation disappear from view. The transformations the lamas speak of eloquently, in several languages, in several media, are mind-to-mind transmissions of insight into the nature of mind, all of which remain invisible to the separators. What once was considered a secret transmission known only to the most intimate associates of the lamas, is now openly explained on YouTube, in books and Chinese social media, yet remains incomprehensible to official minds.

The new order makes education and religious activity two separate categories, separated both spatially and administratively, with no overlap. The separation is explicitly designed for grid management: “both Institute and Larung Monastery must have clear boundaries on all four sides, and after separating the Institute from the [rest of the] area, capacity for grid management and service provision must be strengthened. Separation of functions: With the separation of the Institute from places of religious activity, separation of functions must be actualized, their interrelations properly arranged, and their powers properly specified, thus solving the core issue of their overlap.”

The new order makes education and religious activity two separate categories, separated both spatially and administratively, with no overlap. The separation is explicitly designed for grid management: “both Institute and Larung Monastery must have clear boundaries on all four sides, and after separating the Institute from the [rest of the] area, capacity for grid management and service provision must be strengthened. Separation of functions: With the separation of the Institute from places of religious activity, separation of functions must be actualized, their interrelations properly arranged, and their powers properly specified, thus solving the core issue of their overlap.”

The reduction of Buddhism to dogma is rooted in the late 19th century invention of a Chinese term for religion, borrowed from a Japanese neologism, both a response to the incursions of 19th century Christianity. Until then religion was not a category separate from life. It then became a separate entity, reduced to dogma and study of dogma. “It is very well known that in Chinese, as in many other languages, there is no precise equivalent for the modern western concept ‘religion’. In China a neologism, zongjiao, was formed, or rather adopted from Japanese, to translate the western concept of ‘religion’ as a structured system of beliefs and practices, separate from society, which organizes believers in a church-like organization. It quickly became part of usage from 1901, and since then has retained that sense, which is now outmoded in the social science of religions in the West.”[2]

Dogma can be bundled into a syllabus, and once students have completed the syllabus, they can be ordered to leave.

Today, if Tibetans, preferably only Tibetans registered as residents of Sichuan province, wish to waste their time studying Buddhist dogma, the Institute serves that purpose; but it is clearly only for “locals”. Tibetans from other provinces are permitted only under strict quotas, and nonTibetans clearly no longer qualify at all. “Larung Monastery is a place for religious activity and for providing religious services to the masses of local believers. The study period of monastic students at the Five Sciences Buddhist Institute must be clarified and those who have completed it must be able to return home. The number of new recruits per year should not exceed that year’s quota. Also, the work of grid management and door keeping, divider fencing, red tags for monks, yellow tags for nuns and green tags for lay devotees must be done properly, and the real-name registration and management of the visitor population must be strengthened.”

“Student recruitment standards: First, those who have a firm political stand, accepting the Great Motherland, the Chinese [Zhonghua] people, Chinese culture, the Chinese Communist Party and socialism with Chinese characteristics; second, the number of recruits entering cannot exceed the number of graduates, with each year’s batch not exceeding the quota; third, candidates taking examinations must have an identity card, a religious personnel permit, or an reincarnated lama permit; fourth, students must be recruited from within the Tibetan areas of Sichuan province.”

These restrictions and separations will be as ineffective as the last bout of official destruction at Larung Gar in 2001. While the regulatory detail this time is much greater, and the grid management surveillance technologies more intrusive, the leaders of Larung Gar, used to playing a long game, have not publicly protested, taken the blows as adversities to be expected on the path of purifying the mind, and continue to travel the world teaching inner transformation.

These restrictions and separations will be as ineffective as the last bout of official destruction at Larung Gar in 2001. While the regulatory detail this time is much greater, and the grid management surveillance technologies more intrusive, the leaders of Larung Gar, used to playing a long game, have not publicly protested, taken the blows as adversities to be expected on the path of purifying the mind, and continue to travel the world teaching inner transformation.

Reducing Larung Gar to a curriculum-bound trainer and certifier of professional Buddhists, as if training motor mechanics or park rangers, may hold during official hours, but for sincere Buddhist practitioners the practice is round the clock, with every incentive to persist, as before, in the quiet of one’s own wooden hut, entering and re-entering the pristine nature of mind, untroubled by obstructions and regulatory separations.

[1] https://www.hrw.org/news/2018/01/24/china-new-controls-tibetan-monastery

[2] Vincent Goossaert The Concept of Religion in China and the West, Diogenes, 205: 13–20, 2005